Americans on Everest, 1963 I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TIBET: KAMA CHU and KHARTA VALLEY TREK and FRIENDSHIP HIGHWAY TIBET May, 2019 PART 3 by WILLIAM D BOEHM

TIBET: KAMA CHU AND KHARTA VALLEY TREK AND FRIENDSHIP HIGHWAY TIBET May, 2019 PART 3 BY WILLIAM D BOEHM Yarlung Tsangpo (Brahmaputra) River that flows 3000km (1800 mi) from near Mt Kailish through the deepest canyon in the world, 5300m (17000 ft) below Namcha Barwha 7,782-meter/25,446 ft into the Indian Ganges DAY 4 May 16 We loaded our gear and food for the week khama valley trek on a government bus, interestingly in that it had four fisheye cameras in the front to monitor our conversations and actions. We left Lhasa driving highway G 318, the 830 km (500 mi) long Friendship Highway. We would drive today only partway 270 km (162 mi) to Gyantse to the south. Passed through incredible mountain scenery first driving along the Kyichu Valley and the Lhasa River for an hour before the town of Quxu. Here the Lhasa joins the huge Yarlong Tsampo (Brahmaputra) River. Here we crossed at a narrowing on a bridge and followed along its huge floodplain for an hour before turning off the friendship highway south. The Yarlung Tsangpo begins to the east along its 3,000 kilometer (1,800 mile) course through open valleys on the Tibetan Plateau. With headwaters in western Tibet near Mount Kailash, the river has the highest average elevation 4000 meters (13,000 feet) of any major river in the world. At the eastern end of the Himalayas in southeastern Tibet, the river bends sharply south, cascading through one of most dramatic gorges in the world before Left Yarlong Tsangpo River before canyon, Namcha Barwa Peak 7782 m descending into the lowlands of the Ganges Delta. -

A Statistical Analysis of Mountaineering in the Nepal Himalaya

The Himalaya by the Numbers A Statistical Analysis of Mountaineering in the Nepal Himalaya Richard Salisbury Elizabeth Hawley September 2007 Cover Photo: Annapurna South Face at sunrise (Richard Salisbury) © Copyright 2007 by Richard Salisbury and Elizabeth Hawley No portion of this book may be reproduced and/or redistributed without the written permission of the authors. 2 Contents Introduction . .5 Analysis of Climbing Activity . 9 Yearly Activity . 9 Regional Activity . .18 Seasonal Activity . .25 Activity by Age and Gender . 33 Activity by Citizenship . 33 Team Composition . 34 Expedition Results . 36 Ascent Analysis . 41 Ascents by Altitude Range . .41 Popular Peaks by Altitude Range . .43 Ascents by Climbing Season . .46 Ascents by Expedition Years . .50 Ascents by Age Groups . 55 Ascents by Citizenship . 60 Ascents by Gender . 62 Ascents by Team Composition . 66 Average Expedition Duration and Days to Summit . .70 Oxygen and the 8000ers . .76 Death Analysis . 81 Deaths by Peak Altitude Ranges . 81 Deaths on Popular Peaks . 84 Deadliest Peaks for Members . 86 Deadliest Peaks for Hired Personnel . 89 Deaths by Geographical Regions . .92 Deaths by Climbing Season . 93 Altitudes of Death . 96 Causes of Death . 97 Avalanche Deaths . 102 Deaths by Falling . 110 Deaths by Physiological Causes . .116 Deaths by Age Groups . 118 Deaths by Expedition Years . .120 Deaths by Citizenship . 121 Deaths by Gender . 123 Deaths by Team Composition . .125 Major Accidents . .129 Appendix A: Peak Summary . .135 Appendix B: Supplemental Charts and Tables . .147 3 4 Introduction The Himalayan Database, published by the American Alpine Club in 2004, is a compilation of records for all expeditions that have climbed in the Nepal Himalaya. -

Everest North Side 2020

[email protected] 877-873-5376 Rapid Ascent Everest North Side Expedition 35 days in Tibet / Skill Level: Advanced April 27- May 31, 2020 Land costs- $85,000 *All costs included with the exception of alcohol, in-town meals Difficulty Level Advanced- must be able to climb technical terrain with an alpine pack on your back. You should be comfortable with camp craft in high-altitude camps and be able to perform at a high level for multiple days in a row at altitude. ©2004-2019 All Rights Reserved Alpenglow !1 Overview Alpenglow Expeditions’ Rapid Ascent climbs are an entirely new way to approach big- mountain expeditions. After 15 years of guiding expeditions all over the world, including more than a dozen 8,000-meter peak expeditions, we have refined and distilled the acclimatization and climbing process to maximize safety, health, success, and enjoyment. Please contact us to discuss exactly what these shorter climbs entail. Highlights • Summit the world’s tallest peak from the North Side – without the crowds or the risk of the South Side and Khumbu Icefall • Experience the unique culture, environment and people of Tibet. • Climb Everest in half the time of traditional expeditions, with the North Side’s most professional team and best logistics and infrastructure. Mount Everest, the tallest mountain in the world (29,035’ / 8848m), is an incredible challenge and experience. Alpenglow’s unique format and extensive experience gives us the ability to achieve the highest levels of both safety and success. Since 2015 we have been operating on the North Side of Mount Everest. -

Thirteen Nations on Mount Everest John Cleare 9

Thirteen nations on Mount Everest John Cleare In Nepal the 1971 pre-monsoon season was notable perhaps for two things, first for the worst weather for some seventy years, and second for the failure of an attempt to realise a long-cherished dream-a Cordee internationale on the top of the world. But was it a complete failure? That the much publicised International Himalayan Expedition failed in its climbing objectives is fact, but despite the ill-informed pronouncements of the headline devouring sceptics, safe in their arm-chairs, those of us who were actually members of the expedition have no doubt that internationally we did not fail. The project has a long history, and my first knowledge of it was on a wet winter's night in 1967 at Rusty Baillie's tiny cottage in the Highlands when John Amatt explained to me the preliminary plans for an international expedi tion. This was initially an Anglo-American-Norwegian effort, but as time went by other climbers came and went and various objectives were considered and rejected. Things started to crystallise when Jimmy Roberts was invited to lead the still-embryo expedition, and it was finally decided that the target should be the great South-west face of Mount Everest. However, unaware of this scheme, Norman Dyhrenfurth, leader of the successful American Everest expedition of 1963-film-maker and veteran Himalayan climber-was also planning an international expedition, and he had actually applied for per mission to attempt the South-west face in November 1967, some time before the final target of the other party had even been decided. -

NATURE January 7, 1933

10 NATURE jANUARY 7, 1933 Mount Everest By Col. H. L. CROSTHWAIT, c.I.E. OUNT EVEREST, everyone knows, is the would be through Nepal, but even if the Nepalese M highest mountain in the world. It was Government were willing to permit the passage discovered, and its height determined, during the of its country, the route would be through operations of the Great Trigonometrical Survey trackless leach- infested jungles impossible for of India in the course of carrying out the geodetic pack transport. Added to this, the snow line is triangulation of that country in the years 1849-50. about 2,000 ft. lower on the south side than on The figure adopted, namely, 29,002 ft. above the north, for it is subject to the full force of the mean sea level, was derived from the mean of a monsoon and is probably more deeply eroded and, large number of vertical angles observed to the in consequence, more inaccessible than from the peak from six different stations situated in the Tibet side. For these reasons successive expe plains of India south of Nepal. These stations ditions have taken the longer route, about 350 were at distances varying from 108 to liS miles. miles from Darjeeling via the Chumbi valley, It was not until some months afterwards, when Kampa Dzong and Sheka Dzong, made possible the necessary computations had been completed, since the Tibetan objection to traversing its that the great height of Everest was first realised. territory has been overcome. The actual discovery was made in the computing This route possessed the advantage of passing office at Dehra Dun. -

Nepal 1989 a V Saunders

AV SAUNDERS (Plates 25-27) These notes have been arranged in (more or less) height order. The intention has been to report developments and first ascents completed during the year, rather than to list repeat ascents of existing routes. 1989 was not a good year. There were few new routes, and several fatalities. On Everest (8 848m), reports ofovercrowding have become common place; this year they have been linked to outbreaks ofviral flu. As if this were not enough, there are now perennial arguments about the fixing of the route through the Khumbu icefall. Apparently the earlier expeditions who set up a route often demand payment from the-following expeditions who use the route. During the spring season, the Polish expedition organized by Eugeniusz Chrobak followed a variation on the W ridge route, avoiding the normal Lho La approach. Following a line with minimum avalanche danger, the team climbed Khumbutse (6640m) before descending to the Rongbuk glacier, where they established Camp I at 5850m. The line continued left of previous ascents to gain the W shoulder. Five more camps were established on the ridge and in the Hornbein Couloir. On 24 May Chrobak and Andrzej Marciniak reached the summit. Over the next two days they descended, stripping the camps with the help of two other team members. They reached Camp I in deteriorating weather to join another team arriving from base. The next day all the climbers set out for base, up the 600m fixed ropes over Khumbutse. At 1pm the six climbers were struck by an avalanche which broke the ropes. -

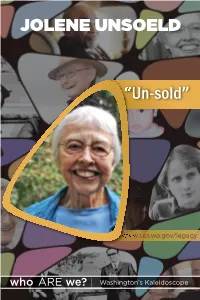

Jolene Unsoeld PDF.Indd

JOLENE UNSOELD “Un-sold” www.sos.wa.gov/legacy who ARE we? | Washington’s Kaleidoscope Jolene addresses an anxious group of employees at Hoquiam Plywood Company in 1988 as the uncertainty over timber supplies intensifies. Kathy Quigg/The Daily World Introduction: “The Meddler” imber workers in her district were mad as hell over set- asides to protect the Northern Spotted Owl. Rush Lim- Tbaugh branded her a “feminazi.” Gun-control advocates called her a flip-flopper. It was the spring of 1994 and Con- gresswoman Jolene Unsoeld of Olympia was girding for the political fight of her life. CSPAN captured her in a bitter de- bate with abortion opponents. Dick Armey, Newt Gingrich’s sidekick, was standing tall in his armadillo-skin cowboy boots, railing against the “self-indulgent conduct” of women who had been “damned careless” with their bodies. As other Republi- cans piled on, Unsoeld’s neck reddened around her trademark pearl choker. Men just don’t get it, she shot back. “Reproductive health is at the very core of a woman’s existence. If you want to be brutally frank, what it compares with is if you had health- care plans that did not cover any illness related to testicles. I “Un-sold” 3 think the women of this country are being tolerant enough to allow you men to vote on this!” Julia Butler Hansen, one of Jolene’s predecessors repre- senting Washington’s complicated 3rd Congressional District, would have loved it. Brutally frank when provoked, Julia was married to a logger and could cuss like one. -

Vallée De Serre Chevalier Briançon

VALLÉE DE SERRE CHEVALIER BRIANÇON www.altus-magazines.com Ski rent - Services Bar-Coff ee shop Concept Store Une nouvelle façon de louer vos skis Serre-Chevalier 1500 Monétier-les-Bains Départ des pistes 0492202688 ALTUS Édito Cela fait dix ans que les magazines Altus ont vu le jour dans les stations transalpines. SERRE CHEVALIER Dix ans que nos équipes ont à cœur de vous faire vivre la diversité de la vie HIVER 2017 - N° 14 en altitude. Les stations de montagne ont cette particularité qu’elles marient la pureté des sites avec la folle activité des vacanciers qui nous rejoignent. Retrouvez ALTUS Vous venez avec vos envies, votre soif de découvrir, votre joie d’être en sur votre mobile. vacances et tout se met en mouvement autour de vous lorsque vous arrivez www.altus-magazines.com ici dans votre station de cœur. Depuis dix ans, Altus vous donne les clés de cette vie hors du commun, faite de saisons, d’activités sportives et de loisirs, d’animations et d’événements. Depuis cinq ans, Altus a accéléré son DIRECTION développement en ouvrant de nouveaux sites prestigieux et en accroissant Directeur de la publication considérablement sa diffusion. Aujourd’hui, Altus est un média multicanal Alain Poncet [email protected] qui se lit sur papier glacé, sur écran, sur tablette et sur téléphone. Directeur d’édition Vous vous sentez bien ici ? Nous aussi ! Et nous allons continuer à vous Roland Claude Durand-Terrasson donner le maximum d’informations et de reportages pour qu’aucun aspect [email protected] de notre vie ne vous échappe. -

New Yorker Magazine

ANNALS OF ADVENTURE THE MANIC MOUNTAIN Ueli Steck and the clash on Everest. BY NICK PAUMGARTEN TH RIFFI G AN H NAT JO 46 THE NEW YO R K E R , J U N E 3 , 2 0 1 3 TNY—2013_06_03—PAGE 46—133SC.—LIVE ART R23602—EXTREMELY CRITICAL PHOTOGRAPH TO BE WATCHED THROUGHOUT THE ENTIRE PRESS RUN 4C eli Steck’s closest brush with death, many of whom work as porters and guides April 27th was the day that a team of or at least the time he thought it like- for the commercial expeditions on Ever- Sherpas were installing the fixed rope. It liestU that he was about to die, came not est. This was on the first day that the is an essential and difficult job, involving when he plummeted seven hundred feet weather cleared for a summit push. The heavy gear and extreme working condi- down the south face of Annapurna, or next day, the crowds went up—hundreds tions on an ice cliff riddled with crevasses. spidered up the Eiger’s fearsome North of aspirants, most of them clients of com- The day before, the Sherpas, with help Face alone and without ropes in under mercial companies, and their Sherpas— from three Western guides, had nearly three hours, or slipped on wet granite and, amid the traffic jam approaching the completed the job but came to an untra- while free-climbing the Golden Gate summit, four climbers died, of exposure versable crevasse, which had forced them route of El Capitan with his wife, on their and cerebral edema. -

Everest 1962 I Maurice Isserman

WIRED MAD, ILL-EQUIPPED AND ADMIRABLE: EVEREST 1962 I MAURICE ISSERMAN ust over a half century Jago, on May 8, 1962, four climbers stood atop a Himalayan icefall, watching the last of their Sherpa porters vanish amid the bright, thin air. For the next month, Woodrow Wilson Sayre, Norman Hansen, Roger Hart and Hans-Peter Duttle would be on their own. 88 T!" #$%%$&'() *$+('(), they’d set o, from a high camp to attempt the -rst ascent of Gyachung Kang, a mountain on the Nepalese- Tibetan border—or so Sayre had told the Nep- alese o.cials back in Kathmandu who granted him the permit. Had his American-Swiss party reached the summit of their announced objec- tive, it would have been an impressive coup, considering that none of them had climbed in the Himalaya before, and only two had ever reached an elevation of more than 20,000 feet. At 26,089 feet (7952m), Gyachung Kang fell just below the arbitrary 8000-meter altitude distinguishing other peaks as the pinnacle of mountaineering ambitions. But Gyachung Kang wouldn’t be climbed [Facing Page] Map of the 1962 team’s approach to Mt. Everest (8848m). Jeremy Collins l [This Page] Woodrow “Woody” Wilson until 1964. /e 1962 expedition had another Sayre on the Nup La. “We made three basic decisions in planning for Everest. We were going without permission, we were objective in mind, located about -fteen miles going without Sherpas, and we were going without oxygen,” Sayre wrote in Four Against Everest. Hans-Peter Duttle collection farther east as the gorak (the Himalayan crow) 0ies. -

Lesson 2: Meet Mount Everest

Everest Education Expedition Curriculum Lesson 2: Meet Mount Everest Created by Montana State University Extended University and Montana NSF EPSCoR http://www.montana.edu/everest Lesson Overview: Begin to unravel the layers of Mount Everest through geography and history. Learn where Mount Everest sits in relation to the world, to Asia, and to surrounding countries. Compare Mount Everest to the highest peak in your region. Trace the routes of the first Americans, and other mountaineers of the past, who summited this peak, and plot the routes this expedition took as you learn the history of the world’s highest mountain. Objectives: Students will be able to: 1. Locate and identify Mount Everest including the two countries it straddles. 2. Locate and identify Granite Peak, the highest point in Montana (or the highest peak in your state or region). 3. Compare and contrast the geography and history of Mount Everest to Granite Peak (or the highest peak in your state or region). 4. Explain the route the first Americans took to summit Mount Everest. Vocabulary: base camp: a place used to store supplies and get ready for climbing located low on the mountain, safe from harsh weather, icefalls, avalanches and the effects of high altitude found higher on the mountain col (coal): a low point on a ridge in between two peaks, also called a “saddle” crevasse (kruh-VAS): a crack in a glacier’s surface that can be very deep and covered by snow elevation: the height of place measured from sea level glacier: a massive river of ice that moves slowly downward -

The Mount Everest Expedition Author(S): C

The Mount Everest Expedition Author(s): C. K. Howard-Bury Source: The Geographical Journal, Vol. 59, No. 2 (Feb., 1922), pp. 81-99 Published by: geographicalj Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1781386 Accessed: 26-06-2016 20:43 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), Wiley are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Geographical Journal This content downloaded from 128.163.2.206 on Sun, 26 Jun 2016 20:43:02 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms The Geographical Journal Vol. LIX No. 2 February 1922 THE MOUNT EVEREST EXPEDITION Lieut.-Colonel C. K. Howard-Bury, D.S.O., Chief of the Expedition Read at the Joint Meeting of the Society and the Alpine Club at the Queeris Hall% 20 December 1921. Maps followingp. 152. OF previously Mount Everest known, and andthe thecountry maps thatof that surrounded district itwere very vague little and was inaccurate. Mount Everest was discovered and measured from the plains of India from a distance of about 150 miles about the year 1850, but it was not given the name of Mount Everest until 1858, in honour of Colonel Everest, who was the Surveyor-General in India at the time of its discovery.