Jolene Unsoeld PDF.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012

Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012 Jennifer E. Manning Information Research Specialist Colleen J. Shogan Deputy Director and Senior Specialist November 26, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL30261 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012 Summary Ninety-four women currently serve in the 112th Congress: 77 in the House (53 Democrats and 24 Republicans) and 17 in the Senate (12 Democrats and 5 Republicans). Ninety-two women were initially sworn in to the 112th Congress, two women Democratic House Members have since resigned, and four others have been elected. This number (94) is lower than the record number of 95 women who were initially elected to the 111th Congress. The first woman elected to Congress was Representative Jeannette Rankin (R-MT, 1917-1919, 1941-1943). The first woman to serve in the Senate was Rebecca Latimer Felton (D-GA). She was appointed in 1922 and served for only one day. A total of 278 women have served in Congress, 178 Democrats and 100 Republicans. Of these women, 239 (153 Democrats, 86 Republicans) have served only in the House of Representatives; 31 (19 Democrats, 12 Republicans) have served only in the Senate; and 8 (6 Democrats, 2 Republicans) have served in both houses. These figures include one non-voting Delegate each from Guam, Hawaii, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Currently serving Senator Barbara Mikulski (D-MD) holds the record for length of service by a woman in Congress with 35 years (10 of which were spent in the House). -

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

"His Trick Knee Is Acting up Again!"

------------_.__ ._------- ..... Will Somebody Tell The PresideDt To Stop Bombing Tlte Parly? RIPON MARCH 1, 1974 Vol. X, No.5 ONE DOLLAR "HIS TRICK KNEE IS ACTING UP AGAIN!" , CONTENTS Commentary Features Weasel Words and Party Principle ............ 4 Politics: Reports .................................................. 8 In an age of political doublespeak, the ritqJallstic State Reports on Florida, New Mexico, Rhode Is compilation of party platforms seems ripe ~9r re land, New Jersey, and Ohio. form. Michigan State Rep. Michael DivelY (R) proposes that a "statement of the majority" be submitted for the quadrennial platforms. Dively served as the chairman of the Revision and Devel Politics: Profiles .................................................... 11 opment Committee of the Michigan GOP, which recommended a similar step for that state party. u.s. Rep. Albert Quie of Minnesota, ranking Re publican member of the House Education and Labor Committee: the profile was prepared by Paul Anderson of the Minnesota Chapter. Constitutional Imbalance ................................ 5 Sen. Charles McC. Mathias (R-Md.) has been c0- chairman, along with Sen. Frank Church (D Politics: People .................................................... 12 Idaho), of the Special Committee on the Termina tion of the National Emergency. According to Mathias, the laxity of controls over emergency presidential powers applies equally to other legis Letters ...................................................................... 14 lation, and he urges that -

The Mountaineer

The Mountaineer 145 ture and making explorations, he was cherishing a plan to examine the Columbia River "from snowflake to brine." He did that very thing and it is claimed that he is the first man to make the entire journey. His adventures, his descriptions of the varying features of the great river, his references to historic explorers of the past, all these combine to make his book a worth while addition to the literature of the Pacific Northwest. The Mountaineer. Edited by MISS LULIE NETTLETON. (Seattle: The Mountaineers, 1921. Pp. 90.) Mazama. Edited by MISS ELLA P. ROBERTS. (Portland: The Mazamas, 1921. Pp. 89.) Mountain climbers in the Pacific Northwest await longingly each year for the appearance of these two books. Always the cen ter of interest in each book is the record of the club's outing during the summer of that year. Other records of mountaineering are in cluded and completed files of these publications are highly prized by librarians and other discriminating collectors. In the summer of 1921, The Mountaineers visited Glacier Peak and Lake Chelan. The story of the outing is told by Robert Walkinshaw and the illustrations are from photographs by members of the party. Other articles include the folowing: "Some Birds and Mammals of Mount Rainier" by Walter P. Taylor, of the Unit ed States Biological Survey; "Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes", by Rodney L. Glisan; "An Ascent of Mount Olympus in Thessaly", by Francis P. Farquhar; "A Mountaineer's Pilgrimage to Pales tine", by William B. Remey; "Light Weight Commissary for Back Packing", by Stuart P. -

1922 Elizabeth T

co.rYRIG HT, 192' The Moootainetro !scot1oror,d The MOUNTAINEER VOLUME FIFTEEN Number One D EC E M BER 15, 1 9 2 2 ffiount Adams, ffiount St. Helens and the (!oat Rocks I ncoq)Ora,tecl 1913 Organized 190!i EDITORlAL ST AitF 1922 Elizabeth T. Kirk,vood, Eclttor Margaret W. Hazard, Associate Editor· Fairman B. L�e, Publication Manager Arthur L. Loveless Effie L. Chapman Subsc1·iption Price. $2.00 per year. Annual ·(onl�') Se,·ent�·-Five Cents. Published by The Mountaineers lncorJ,orated Seattle, Washington Enlerecl as second-class matter December 15, 19t0. at the Post Office . at . eattle, "\Yash., under the .-\0t of March 3. 1879. .... I MOUNT ADAMS lllobcl Furrs AND REFLEC'rION POOL .. <§rtttings from Aristibes (. Jhoutribes Author of "ll3ith the <6obs on lltount ®l!!mµus" �. • � J� �·,,. ., .. e,..:,L....._d.L.. F_,,,.... cL.. ��-_, _..__ f.. pt",- 1-� r�._ '-';a_ ..ll.-�· t'� 1- tt.. �ti.. ..._.._....L- -.L.--e-- a';. ��c..L. 41- �. C4v(, � � �·,,-- �JL.,�f w/U. J/,--«---fi:( -A- -tr·�� �, : 'JJ! -, Y .,..._, e� .,...,____,� � � t-..__., ,..._ -u..,·,- .,..,_, ;-:.. � --r J /-e,-i L,J i-.,( '"'; 1..........,.- e..r- ,';z__ /-t.-.--,r� ;.,-.,.....__ � � ..-...,.,-<. ,.,.f--· :tL. ��- ''F.....- ,',L � .,.__ � 'f- f-� --"- ��7 � �. � �;')'... f ><- -a.c__ c/ � r v-f'.fl,'7'71.. I /!,,-e..-,K-// ,l...,"4/YL... t:l,._ c.J.� J..,_-...A 'f ',y-r/� �- lL.. ��•-/IC,/ ,V l j I '/ ;· , CONTENTS i Page Greetings .......................................................................tlristicles }!}, Phoiitricles ........ r The Mount Adams, Mount St. Helens, and the Goat Rocks Outing .......................................... B1/.ith Page Bennett 9 1 Selected References from Preceding Mount Adams and Mount St. -

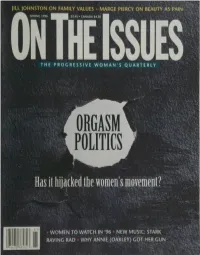

View Entire Issue in Pdf Format

JILL JOHNSTON ON FAMILY VALUES MARGE PIERCY ON BEAUTY AS PAIN SPRING 1996 $3,95 • CANADA $4.50 THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S QUARTERLY POLITICS Has it hijackedthe women's movement? WOMEN TO WATCH IN '96 NEW MUSIC: STARK RAVING RAD WHY ANNIE (OAKLEY) GOT HER GUN 7UU70 78532 The Word 9s Spreading... Qcaj filewsfrom a Women's Perspective Women's Jrom a Perspective Or Call /ibout getting yours At Home (516) 696-99O9 SPRING 1996 VOLUME V • NUMBER TWO ON IKE ISSUES THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S QUARTERLY features 18 COVER STORY How Orgasm Politics Has Hi j acked the Women's Movement SHEILAJEFFREYS Why has the Big O seduced so many feminists—even Ms.—into a counterrevolution from within? 22 ELECTION'96 Running Scared KAY MILLS PAGE 26 In these anxious times, will women make a difference? Only if they're on the ballot. "Let the girls up front!" 26 POP CULTURE Where Feminism Rocks MARGARET R. SARACO From riot grrrls to Rasta reggae, political music in the '90s is raw and real. 30 SELF-DEFENSE Why Annie Got Her Gun CAROLYN GAGE Annie Oakley trusted bullets more than ballots. She knew what would stop another "he-wolf." 32 PROFILE The Hot Politics of Italy's Ice Maiden PEGGY SIMPSON At 32, Irene Pivetti is the youngest speaker of the Italian Parliament hi history. PAGE 32 36 ACTIVISM Diary of a Rape-Crisis Counselor KATHERINE EBAN FINKELSTEIN Italy's "femi Newtie" Volunteer work challenged her boundaries...and her love life. 40 PORTFOLIO Not Just Another Man on a Horse ARLENE RAVEN Personal twists on public art. -

Mazama Research Reports Vol. 1–22PDF Document

8/13/2020 Reports of Scientific Investigations sponsored by Mazama Research Grants Page 1 REPORTS OF SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATIONS Sponsored by Mazama Research Funds Index to volumes 1-22 and Separate Reports 1-5 8/13/2020 Reports of Scientific Investigations sponsored by Mazama Research Grants Page 2 Table of Contents Volume 3 1. A study of the primary productivity rate of South Volume 1 Cascade Glacier: correlation with ice worm 1. Microenvironmental modifications to favor seed populations. Bland, Jeffrey and Wilson, Kathy germination in distributed sub-alpine 2. Environment of tundra vegetation of Steen’s environments, Mount Rainier National Park, Mountain. Collins, Paul Washington. Ahlstrand, Gary M. 3. The effect of an outdoor experience on self 2. Some effects of snowmobiles in the High attitudes and behavior of mentally retarded Cascades. Bowerman, Jay adults. Fullerton, Ann 3. Glacial geology of the Mountain Lake Wilderness 4. Geology of the Bull of the Woods area. Jackson, and adjacent parts of the Cascade Range, James S. Oregon. Craver, Gary Alan 5. Investigation of the geology structure of Northwest 4. A pilot biological survey of the Sky Lakes Oregon by the interpretations of a gravity Wilderness study area. Cross, Stephen P and traverse southwest of Portland, Oregon, 1977. Lang, Frank A. Jones, Terry 5. High mountain hummingbird feeding territories in 6. Attitude change related to a course in backpacking relation to food supplies. Gass, Lee at the University of Montana. Long, Eleanor 6. A limnological study of Shadow Lake, a subalpine V.1974 late at Mount Rainier National Park, 7. Preliminary report of the 1976 Awlinyak Peaks Washington. -

Nixon's Caribbean Milieu, 1950–1968

Dark Quadrant: Organized Crime, Big Business, and the Corruption of American Democracy Online Appendix: Nixon’s Caribbean Milieu, 1950–1968 By Jonathan Marshall “Though his working life has been passed chiefly on the far shores of the continent, close by the Pacific and the Atlantic, some emotion always brings Richard Nixon back to the Caribbean waters off Key Biscayne and Florida.”—T. H. White, The Making of the President, 19681 Richard Nixon, like millions of other Americans, enjoyed Florida and the nearby islands of Cuba and the Bahamas as refuges where he could leave behind his many cares and inhibitions. But he also returned again and again to the region as an important ongoing source of political and financial support. In the process, the lax ethics of its shadier operators left its mark on his career. This Sunbelt frontier had long attracted more than its share of sleazy businessmen, promoters, and politicians who shared a get-rich-quick spirit. In Florida, hustlers made quick fortunes selling worthless land to gullible northerners and fleecing vacationers at illegal but wide-open gambling joints. Sheriffs and governors protected bookmakers and casino operators in return for campaign contributions and bribes. In nearby island nations, as described in chapter 4, dictators forged alliances with US mobsters to create havens for offshore gambling and to wield political influence in Washington. Nixon’s Caribbean milieu had roots in the mobster-infested Florida of the 1940s. He was introduced to that circle through banker and real estate investor Bebe Rebozo, lawyer Richard Danner, and Rep. George Smathers. Later this chapter will explore some of the diverse connections of this group by following the activities of Danner during the 1968 presidential campaign, as they touched on Nixon’s financial and political ties to Howard Hughes, the South Florida crime organization of Santo Trafficante, and mobbed-up hotels and casinos in Las Vegas and Miami. -

GPO-CRECB-1987-Pt14-1-3.Pdf

18684 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS July 1, 1987 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS INTRODUCTION OF THE RE Unlike pensions which have legal protec Finally, VRHP's could have another pro TIREE HEALTH PROTECTION tions for retirees, the retirees of LTV were left found effect. VRHP's could provide the engine ACT OF 1987 holding the bag for their health coverage. to get this Nation's evolving long-term care in The LTV Corp. retirees sought and received surance market going. relief from the Congress. The Congress re Until now, health insurers have been reluc HON. ROD CHANDLER quired that the company maintain retiree tant to develop long-term care coverage be OF WASHINGTON health coverage, at least temporarily. cause it has had to be sold on a retail basis IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES It is not appropriate for the Congress to individual by individual. assume such a role every time a firm gets into Employer participation has been missing in Wednesday, July 1, 1987 trouble. the long-term care area. So, employer groups Mr. CHANDLER. Mr. Speaker, I rise today VRHP's would not help LTV or its retirees. have not been open to insurers for long-term to introduce the Retiree Health Protection Act But, VRHP's could forestall comparable prob care coverage. of 1987, H.R. 2860. The co-author of this leg lems for other retirees and their former em The prefunding vehicle provided by VRHP's islation is my distinguished colleague from ployers. VRHP's would enable employers to may give employers the incentive to offer Alabama, Representative RONNIE FLIPPO. -

THE FOLEY REPORT Director’S Update

2018 Washington State Attorney General Bob Ferguson “Defending the Dreamers” Page 16 THE FOLEY REPORT Director’s Update In 2017 the Cambridge Dictionary chose “populism” as its word of the year. In recent years, movements like the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street thrived, and populist Director Cornell W. Clayton politicians like Donald Trump, Bernie Sanders, Sarah 316 Bryan Hall Palin, and Elizabeth Warren have become political stars. Washington State University PO Box 645136 In Europe, Britain voted to leave the EU, populist Cornell Clayton Pullman, WA 99164-5136 politicians like Marine Le Pen in France or Boris Phone 509-335-3477 Johnson in the UK became famous, while Italy, Hungary, Greece and Poland have all elected [email protected] populist governments. foley.wsu.edu Established at Washington State University We are in a populist moment, but what is populism? What explains its growing appeal? And in 1995, the mission of the institute should it concern us? The Foley Institute has hosted several events in recent years exploring is to foster congressional studies, civic various aspects of populist politics, and so I thought I would use my note today to share some education, public service, and public thoughts on this topic. policy research in a non-partisan, cross-disciplinary setting. First, populism is not an ideology that is committed to specific political goals or policies. Rather, it is a style of political discourse or thinking, one which views politics as a conflict Distinguished Professors between corrupt elites (political, economic, intellectual or cultural) and a virtuous “people” Cornell W. Clayton, (the silent majority, the forgotten man, “real” Americans). -

461 Indians on the Bolivian Side Pomaratu. They Climbed to Its Top

CLIMBS AND EXPEDITIONS 461 Indians on the Bolivian side Pomaratu. They climbed to its top on October 12, placing only one camp at 17,000 feet. As far as is known, Parinacota (20,768 feet) had been climbed twice before. Pomarata, which seems to be the correct name (20,473 feet) was claimed as a first ascent by Bolivians in 1946, but there is no certainty of this climb. The top of Pomarata is heavily glaciated. OSCAR GONZALEZ FBRRAN, Chb Andho de Chile Argentina El Tore. A most extraordinary find was made by two climbers, Erich Groch and Antonio Beorchia, when on January 28 they made what they had assumed would be the first ascent of El Toro (20,952 feet), in the Province of San Juan. On the summit they found what appeared to be a human head lying on the surface. When they tried to lift it, they dis- covered it was still attached to a mummified body. They returned with others to retrieve the body, which had been there at least 450 years, a sacrificial victim with a wound at the back of the head. He had been a young man of between 15 to 20 years. He was in a sitting position with his hands crossed below his knees, dressed in gray trousers with red trimmings, a red wool cap and a poncho. Under the body a rat was found, also mummified. Central Argentina. The highest peak in the Mo?zgotes group, a snow and ice peak about 19,350 feet high, was climbed in January by R. -

July 24, 2018 Federal Election Commission Lisa J. Stevenson

July 24, 2018 Federal Election Commission Lisa J. Stevenson, Acting General Counsel Office of the General Counsel 1050 First Street, NE Washington, DC 20463 Submitted via email and U.S.P.S. Petition for Rulemaking to Revise and Amend Regulations Relating to the Personal Use of Leadership PAC Funds Dear Ms. Stevenson, Pursuant to 11 C.F.R. § 200.1 et seq., Campaign Legal Center (“CLC”), Issue One, and former United States Representatives Rod Chandler (R-WA), Larry LaRocco (D- ID), Peter Smith (R-VT), Claudine Schneider (R-RI), and John Tanner (D-TN) hereby petition the Federal Election Commission to open a rulemaking to revise and amend 11 C.F.R. § 113.1(g), the regulation defining the personal use of campaign funds, to clarify the application of this rule to so-called “Leadership PACs.” Congress has prohibited “any contribution accepted by a candidate” and “any other donation received by an individual as support for activities of the individual as a holder of Federal office” from being converted to the “personal use” of the candidate or any other person. 52 U.S.C. §§ 30114(a), 30114(b)(1). By its very terms, this statutory personal use prohibition is applicable to any contribution received by a candidate’s leadership PAC, and Commission rules should reflect this clear statutory mandate. Although the Commission has allowed for the creation of leadership PACs to permit candidates and officeholders to support other candidates or party committees, the attached report demonstrates that leadership PACs are commonly used as slush funds to subsidize officeholders’ lifestyles. As the analysis in the attached report (“All Expenses Paid: How Leadership PACs Became Politicians’ Preferred Ticket to Luxury Living”) demonstrates, over the past five years, only 45% of all leadership PAC spending has gone towards contributions to other candidates or political committees—and many leadership PACs give even less.