Methods for Measuring Frost Tolerance of Conifers: a Systematic Map

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Austrocedrus Forests of South America Are Pivotal Ecosystems at Risk Due to the Emergence of an Exotic Tree Disease

GSDR 2015 Brief Austrocedrus forests of South America are pivotal ecosystems at risk due to the emergence of an exotic tree disease: can a joint effort of research and policy save them? By Alina Greslebin 1, Maria Laura Vélez 2 and Matteo Garbelotto 3. 1CONICET-Universidad Nacional de la Patagonia SJB, Argentina; 2CONICET-Centro de Investigación y Extensión Forestal Andino Patagónico (CIEFAP), Argentina; 3University of California Berkeley, USA Introduction A. chilensis covers today a total estimated area of Human expansion, global movement, and climate 185,000 ha in South America. As a dominant forest change have led to a number of emerging and re- species, its role in supporting biodiversity, generating emerging diseases. The decline of biodiversity due to shelter for wildlife, as well as preventing soil erosion emerging plants pathogens may cause habitat and and preserving water quality is well understood. Along wildlife loss and declines in ecosystem services. This, in with Araucaria araucana, it is the tree species that turn, often results in lower human well-being. Reports grows furthest into the ecotone zone within the of emerging plant diseases are constantly on the rise, Patagonia steppe, where it plays a key role preventing and often they appear to be linked to the commercial desertification. There are however additional functions trade of plants and plant products. While there are this tree provides, including the production of valuable several examples of decimation or extinction of plant timber and the generation of an environment ideal for hosts affected by invasive forest diseases, there are no cattle grazing, recreational and touristic activities and known cases of invasive forest diseases successfully for human settlement. -

New Fossil Plant Discovery Links Patagonia to New Guinea in a Warmer Past 10 November 2009

New fossil plant discovery links Patagonia to New Guinea in a warmer past 10 November 2009 insect-feeding richness found at the fossil sites. The specimen shown is coalified with light patches of facial leaf cuticle visible overlying coal. Note opposite branching, enlarged lateral leaves, and light-colored amber in foliar resin canals. Credit: Image credit: P. Wilf. Fossil plants are windows to the past, providing us with clues as to what our planet looked like millions of years ago. Not only do fossils tell us which species were present before human-recorded history, but they can provide information about the climate and how and when lineages may have dispersed around the world. Identifying fossil plants can be tricky, however, when plant organs fail to be This is foliage of Papuacedrus prechilensis (Berry) Wilf preserved or when only a few sparse parts can be et al., comb. nov. (Cupressaceae), from the middle found. Eocene Río Pichileufú flora of Río Negro Province, Patagonia, Argentina. The monotypic genus In the November issue of the American Journal of Papuacedrus is today restricted to montane rainforests Botany, Peter Wilf (of Pennsylvania State of New Guinea and the Moluccas, but its scarce fossil University) and his U.S. and Argentine colleagues record includes Tasmania and Antarctica. Wilf et al. published their recent discovery of abundant describe a suite of well-preserved specimens excavated from early and middle Eocene sites in Patagonia, fossilized specimens of a conifer previously known including an immature seed cone attached to foliage with as "Libocedrus" prechilensis found in Argentinean organic preservation, bearing numerous characters Patagonia. -

Extinction, Transoceanic Dispersal, Adaptation and Rediversification

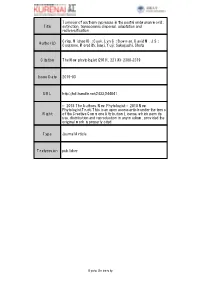

Turnover of southern cypresses in the post-Gondwanan world: Title extinction, transoceanic dispersal, adaptation and rediversification Crisp, Michael D.; Cook, Lyn G.; Bowman, David M. J. S.; Author(s) Cosgrove, Meredith; Isagi, Yuji; Sakaguchi, Shota Citation The New phytologist (2019), 221(4): 2308-2319 Issue Date 2019-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/244041 © 2018 The Authors. New Phytologist © 2018 New Phytologist Trust; This is an open access article under the terms Right of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University Research Turnover of southern cypresses in the post-Gondwanan world: extinction, transoceanic dispersal, adaptation and rediversification Michael D. Crisp1 , Lyn G. Cook2 , David M. J. S. Bowman3 , Meredith Cosgrove1, Yuji Isagi4 and Shota Sakaguchi5 1Research School of Biology, The Australian National University, RN Robertson Building, 46 Sullivans Creek Road, Acton (Canberra), ACT 2601, Australia; 2School of Biological Sciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Qld 4072, Australia; 3School of Natural Sciences, The University of Tasmania, Private Bag 55, Hobart, Tas 7001, Australia; 4Graduate School of Agriculture, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan; 5Graduate School of Human and Environmental Studies, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan Summary Author for correspondence: Cupressaceae subfamily Callitroideae has been an important exemplar for vicariance bio- Michael D. Crisp geography, but its history is more than just disjunctions resulting from continental drift. We Tel: +61 2 6125 2882 combine fossil and molecular data to better assess its extinction and, sometimes, rediversifica- Email: [email protected] tion after past global change. -

The Role of Fir Species in the Silviculture of British Forests

Kastamonu Üni., Orman Fakültesi Dergisi, 2012, Özel Sayı: 15-26 Kastamonu Univ., Journal of Forestry Faculty, 2012, Special Issue The Role of True Fir Species in the Silviculture of British Forests: past, present and future W.L. MASON Forest Research, Northern Research Station, Roslin, Midlothian, Scotland EH25 9SY, U.K. E.mail:[email protected] Abstract There are no true fir species (Abies spp.) native to the British Isles: the first to be introduced was Abies alba in the 1600s which was planted on some scale until the late 1800s when it proved vulnerable to an insect pest. Thereafter interest switched to North American species, particularly grand (Abies grandis) and noble (Abies procera) firs. Provenance tests were established for A. alba, A. amabilis, A. grandis, and A. procera. Other silver fir species were trialled in forest plots with varying success. Although species such as grand fir have proved highly productive on favourable sites, their initial slow growth on new planting sites and limited tolerance of the moist nutrient-poor soils characteristic of upland Britain restricted their use in the afforestation programmes of the last century. As a consequence, in 2010, there were about 8000 ha of Abies species in Britain, comprising less than one per cent of the forest area. Recent species trials have confirmed that best growth is on mineral soils and that, in open ground conditions, establishment takes longer than for other conifers. However, changes in forest policies increasingly favour the use of Continuous Cover Forestry and the shade tolerant nature of many fir species makes them candidates for use with selection or shelterwood silvicultural systems. -

Edition 2 from Forest to Fjaeldmark the Vegetation Communities Highland Treeless Vegetation

Edition 2 From Forest to Fjaeldmark The Vegetation Communities Highland treeless vegetation Richea scoparia Edition 2 From Forest to Fjaeldmark 1 Highland treeless vegetation Community (Code) Page Alpine coniferous heathland (HCH) 4 Cushion moorland (HCM) 6 Eastern alpine heathland (HHE) 8 Eastern alpine sedgeland (HSE) 10 Eastern alpine vegetation (undifferentiated) (HUE) 12 Western alpine heathland (HHW) 13 Western alpine sedgeland/herbland (HSW) 15 General description Rainforest and related scrub, Dry eucalypt forest and woodland, Scrub, heathland and coastal complexes. Highland treeless vegetation communities occur Likewise, some non-forest communities with wide within the alpine zone where the growth of trees is environmental amplitudes, such as wetlands, may be impeded by climatic factors. The altitude above found in alpine areas. which trees cannot survive varies between approximately 700 m in the south-west to over The boundaries between alpine vegetation communities are usually well defined, but 1 400 m in the north-east highlands; its exact location depends on a number of factors. In many communities may occur in a tight mosaic. In these parts of Tasmania the boundary is not well defined. situations, mapping community boundaries at Sometimes tree lines are inverted due to exposure 1:25 000 may not be feasible. This is particularly the or frost hollows. problem in the eastern highlands; the class Eastern alpine vegetation (undifferentiated) (HUE) is used in There are seven specific highland heathland, those areas where remote sensing does not provide sedgeland and moorland mapping communities, sufficient resolution. including one undifferentiated class. Other highland treeless vegetation such as grasslands, herbfields, A minor revision in 2017 added information on the grassy sedgelands and wetlands are described in occurrence of peatland pool complexes, and other sections. -

Potential Impact of Climate Change

Adhikari et al. Journal of Ecology and Environment (2018) 42:36 Journal of Ecology https://doi.org/10.1186/s41610-018-0095-y and Environment RESEARCH Open Access Potential impact of climate change on the species richness of subalpine plant species in the mountain national parks of South Korea Pradeep Adhikari, Man-Seok Shin, Ja-Young Jeon, Hyun Woo Kim, Seungbum Hong and Changwan Seo* Abstract Background: Subalpine ecosystems at high altitudes and latitudes are particularly sensitive to climate change. In South Korea, the prediction of the species richness of subalpine plant species under future climate change is not well studied. Thus, this study aims to assess the potential impact of climate change on species richness of subalpine plant species (14 species) in the 17 mountain national parks (MNPs) of South Korea under climate change scenarios’ representative concentration pathways (RCP) 4.5 and RCP 8.5 using maximum entropy (MaxEnt) and Migclim for the years 2050 and 2070. Results: Altogether, 723 species occurrence points of 14 species and six selected variables were used in modeling. The models developed for all species showed excellent performance (AUC > 0.89 and TSS > 0.70). The results predicted a significant loss of species richness in all MNPs. Under RCP 4.5, the range of reduction was predicted to be 15.38–94.02% by 2050 and 21.42–96.64% by 2070. Similarly, under RCP 8.5, it will decline 15.38–97.9% by 2050 and 23.07–100% by 2070. The reduction was relatively high in the MNPs located in the central regions (Songnisan and Gyeryongsan), eastern region (Juwangsan), and southern regions (Mudeungsan, Wolchulsan, Hallasan, and Jirisan) compared to the northern and northeastern regions (Odaesan, Seoraksan, Chiaksan, and Taebaeksan). -

Conifer Quarterly

Conifer Quarterly Vol. 24 No. 4 Fall 2007 Picea pungens ‘The Blues’ 2008 Collectors Conifer of the Year Full-size Selection Photo Credit: Courtesy of Stanley & Sons Nursery, Inc. CQ_FALL07_FINAL.qxp:CQ 10/16/07 1:45 PM Page 1 The Conifer Quarterly is the publication of the American Conifer Society Contents 6 Competitors for the Dwarf Alberta Spruce by Clark D. West 10 The Florida Torreya and the Atlanta Botanical Garden by David Ruland 16 A Journey to See Cathaya argyrophylla by William A. McNamara 19 A California Conifer Conundrum by Tim Thibault 24 Collectors Conifer of the Year 29 Paul Halladin Receives the ACS Annual Award of Merits 30 Maud Henne Receives the Marvin and Emelie Snyder Award of Merit 31 In Search of Abies nebrodensis by Daniel Luscombe 38 Watch Out for that Tree! by Bruce Appeldoorn 43 Andrew Pulte awarded 2007 ACS $1,000 Scholarship by Gerald P. Kral Conifer Society Voices 2 President’s Message 4 Editor’s Memo 8 ACS 2008 National Meeting 26 History of the American Conifer Society – Part One 34 2007 National Meeting 42 Letters to the Editor 44 Book Reviews 46 ACS Regional News Vol. 24 No. 4 CONIFER QUARTERLY 1 CQ_FALL07_FINAL.qxp:CQ 10/16/07 1:45 PM Page 2 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Conifer s I start this letter, we are headed into Afall. In my years of gardening, this has been the most memorable year ever. It started Quarterly with an unusually warm February and March, followed by the record freeze in Fall 2007 Volume 24, No 4 April, and we just broke a record for the number of consecutive days in triple digits. -

Plant Life of Western Australia

INTRODUCTION The characteristic features of the vegetation of Australia I. General Physiography At present the animals and plants of Australia are isolated from the rest of the world, except by way of the Torres Straits to New Guinea and southeast Asia. Even here adverse climatic conditions restrict or make it impossible for migration. Over a long period this isolation has meant that even what was common to the floras of the southern Asiatic Archipelago and Australia has become restricted to small areas. This resulted in an ever increasing divergence. As a consequence, Australia is a true island continent, with its own peculiar flora and fauna. As in southern Africa, Australia is largely an extensive plateau, although at a lower elevation. As in Africa too, the plateau increases gradually in height towards the east, culminating in a high ridge from which the land then drops steeply to a narrow coastal plain crossed by short rivers. On the west coast the plateau is only 00-00 m in height but there is usually an abrupt descent to the narrow coastal region. The plateau drops towards the center, and the major rivers flow into this depression. Fed from the high eastern margin of the plateau, these rivers run through low rainfall areas to the sea. While the tropical northern region is characterized by a wet summer and dry win- ter, the actual amount of rain is determined by additional factors. On the mountainous east coast the rainfall is high, while it diminishes with surprising rapidity towards the interior. Thus in New South Wales, the yearly rainfall at the edge of the plateau and the adjacent coast often reaches over 100 cm. -

Guidelines to Minimize the Impacts of Hemlock Woolly Adelgid

United States Department of Eastern Hemlock Agriculture Forest Service Forests: Guidelines to Northeastern Area State & Private Minimize the Impacts of Forestry Morgantown, WV Hemlock Woolly Adelgid NA-TP-03-04 Cover photographs (clockwise from upper left): hemlock woolly adelgid (Adelges tsugae) ovisacs on hemlock needles (Michael Montgomery, USDA Forest Service), hemlock-shaded stream (Jeff Ward, The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station), and black-throated green warbler (Mike Hopiak, Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology). Information about pesticides appears in this publication. Publication of this information does not constitute endorsement or recommendation by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, nor does it imply that all uses discussed have been registered. Use of most pesticides is regulated by State and Federal law. Applicable regulations must be obtained from appropriate regulatory agencies. CAUTION: Pesticides can be injurious to humans, domestic animals, desirable plants, and fish or other wildlife if not handled or applied properly. Use all pesticides selectively and carefully. Follow recommended practices given on the label for use and disposal of pesticides and pesticide containers. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities based on race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, and marital or familial status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at 202-720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call 202-720-5964 (voice or TDD). -

Bgci's Plant Conservation Programme in China

SAFEGUARDING A NATION’S BOTANICAL HERITAGE – BGCI’S PLANT CONSERVATION PROGRAMME IN CHINA Images: Front cover: Rhododendron yunnanense , Jian Chuan, Yunnan province (Image: Joachim Gratzfeld) Inside front cover: Shibao, Jian Chuan, Yunnan province (Image: Joachim Gratzfeld) Title page: Davidia involucrata , Daxiangling Nature Reserve, Yingjing, Sichuan province (Image: Xiangying Wen) Inside back cover: Bretschneidera sinensis , Shimen National Forest Park, Guangdong province (Image: Xie Zuozhang) SAFEGUARDING A NATION’S BOTANICAL HERITAGE – BGCI’S PLANT CONSERVATION PROGRAMME IN CHINA Joachim Gratzfeld and Xiangying Wen June 2010 Botanic Gardens Conservation International One in every five people on the planet is a resident of China But China is not only the world’s most populous country – it is also a nation of superlatives when it comes to floral diversity: with more than 33,000 native, higher plant species, China is thought to be home to about 10% of our planet’s known vascular flora. This botanical treasure trove is under growing pressure from a complex chain of cause and effect of unprecedented magnitude: demographic, socio-economic and climatic changes, habitat conversion and loss, unsustainable use of native species and introduction of exotic ones, together with environmental contamination are rapidly transforming China’s ecosystems. There is a steady rise in the number of plant species that are on the verge of extinction. Great Wall, Badaling, Beijing (Image: Zhang Qingyuan) Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI) therefore seeks to assist China in its endeavours to maintain and conserve the country’s extraordinary botanical heritage and the benefits that this biological diversity provides for human well-being. It is a challenging venture and represents one of BGCI’s core practical conservation programmes. -

Medicinal Plant Conservation

MEDICINAL Medicinal Plant PLANT SPECIALIST GROUP Conservation Silphion Volume 11 Newsletter of the Medicinal Plant Specialist Group of the IUCN Species Survival Commission Chaired by Danna J. Leaman Chair’s note . 2 Sustainable sourcing of Arnica montana in the International Standard for Sustainable Wild Col- Apuseni Mountains (Romania): A field project lection of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants – Wolfgang Kathe . 27 (ISSC-MAP) – Danna Leaman . 4 Rhodiola rosea L., from wild collection to field production – Bertalan Galambosi . 31 Regional File Conservation data sheet Ginseng – Dagmar Iracambi Medicinal Plants Project in Minas Gerais Lange . 35 (Brazil) and the International Standard for Sus- tainable Wild Collection of Medicinal and Aro- Conferences and Meetings matic Plants (ISSC-MAP) – Eleanor Coming up – Natalie Hofbauer. 38 Gallia & Karen Franz . 6 CITES News – Uwe Schippmann . 38 Conservation aspects of Aconitum species in the Himalayas with special reference to Uttaran- Recent Events chal (India) – Niranjan Chandra Shah . 9 Conservation Assessment and Management Prior- Promoting the cultivation of medicinal plants in itisation (CAMP) for wild medicinal plants of Uttaranchal, India – Ghayur Alam & Petra North-East India – D.K. Ved, G.A. Kinhal, K. van de Kop . 15 Ravikumar, R. Vijaya Sankar & K. Haridasan . 40 Taxon File Notices of Publication . 45 Trade in East African Aloes – Sara Oldfield . 19 Towards a standardization of biological sustain- List of Members. 48 ability: Wildcrafting Rhatany (Krameria lap- pacea) in Peru – Maximilian -

PHYLOGENETIC RELATIONSHIPS of TORREYA (TAXACEAE) INFERRED from SEQUENCES of NUCLEAR RIBOSOMAL DNA ITS REGION Author(S): Jianhua Li, Charles C

PHYLOGENETIC RELATIONSHIPS OF TORREYA (TAXACEAE) INFERRED FROM SEQUENCES OF NUCLEAR RIBOSOMAL DNA ITS REGION Author(s): Jianhua Li, Charles C. Davis, Michael J. Donoghue, Susan Kelley and Peter Del Tredici Source: Harvard Papers in Botany, Vol. 6, No. 1 (July 2001), pp. 275-281 Published by: Harvard University Herbaria Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41761652 Accessed: 14-06-2016 15:35 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41761652?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Harvard University Herbaria is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Harvard Papers in Botany This content downloaded from 128.103.224.4 on Tue, 14 Jun 2016 15:35:14 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms PHYLOGENETIC RELATIONSHIPS OF TORREYA (TAXACEAE) INFERRED FROM SEQUENCES OF NUCLEAR RIBOSOMAL DNA ITS REGION Jianhua Li,1 Charles C. Davis,2 Michael J. Donoghue,3 Susan Kelley,1 And Peter Del Tredici1 Abstract. Torreya, composed of five to seven species, is distributed disjunctly in eastern Asia and the eastern and western United States.