Syntax and Semantics of the Existentials Ar-U and I-Ru in Japanese"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Affectedness Constructions: How Languages Indicate Positive and Negative Events

Affectedness Constructions: How languages indicate positive and negative events by Tomoko Yamashita Smith B.S. (Doshisha Women’s College) 1987 M.A. (San Jose State University) 1995 M.A. (University of California, Berkeley) 1997 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor Eve E. Sweetser Professor Soteria Svorou Professor Charles J. Fillmore Professor Yoko Hasegawa Fall 2005 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Affectedness Constructions: How languages indicate positive and negative events Copyright 2005 by Tomoko Yamashita Smith Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Abstract Affectedness constructions: How languages indicate positive and negative events by Tomoko Yamashita Smith Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Eve E. Sweetser, Chair This dissertation is a cross-linguistic study of what I call “affectedness constructions” (ACs) that express the notions of benefit and adversity. Since there is little research dealing with both benefactives and adversatives at the same time, the main goal of this dissertation is to establish AC as a grammatical category. First, many instances of ACs in the world are provided to show both the diversity of ACs and the consistent patterns among them. In some languages, a single construction indicates either benefit or adversity, depending on the context, while in others there is one or more individual benefactive and/or adversative construction(s). Since the event types that ACs indicate appear limited, I categorize the constructions by event type and discuss Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Introduction to Japanese Computational Linguistics Francis Bond and Timothy Baldwin

1 Introduction to Japanese Computational Linguistics Francis Bond and Timothy Baldwin The purpose of this chapter is to provide a brief introduction to the Japanese language, and natural language processing (NLP) research on Japanese. For a more complete but accessible description of the Japanese language, we refer the reader to Shibatani (1990), Backhouse (1993), Tsujimura (2006), Yamaguchi (2007), and Iwasaki (2013). 1 A Basic Introduction to the Japanese Language Japanese is the official language of Japan, and belongs to the Japanese language family (Gordon, Jr., 2005).1 The first-language speaker pop- ulation of Japanese is around 120 million, based almost exclusively in Japan. The official version of Japanese, e.g. used in official settings andby the media, is called hyōjuNgo “standard language”, but Japanese also has a large number of distinctive regional dialects. Other than lexical distinctions, common features distinguishing Japanese dialects are case markers, discourse connectives and verb endings (Kokuritsu Kokugo Kenkyujyo, 1989–2006). 1There are a number of other languages in the Japanese language family of Ryukyuan type, spoken in the islands of Okinawa. Other languages native to Japan are Ainu (an isolated language spoken in northern Japan, and now almost extinct: Shibatani (1990)) and Japanese Sign Language. Readings in Japanese Natural Language Processing. Francis Bond, Timothy Baldwin, Kentaro Inui, Shun Ishizaki, Hiroshi Nakagawa and Akira Shimazu (eds.). Copyright © 2016, CSLI Publications. 1 Preview 2 / Francis Bond and Timothy Baldwin 2 The Sound System Japanese has a relatively simple sound system, made up of 5 vowel phonemes (/a/,2 /i/, /u/, /e/ and /o/), 9 unvoiced consonant phonemes (/k/, /s/,3 /t/,4 /n/, /h/,5 /m/, /j/, /ó/ and /w/), 4 voiced conso- nants (/g/, /z/,6 /d/ 7 and /b/), and one semi-voiced consonant (/p/). -

A General Overview of Irabu Ryukyuan, a Southern Ryukyuan Language of the Japonic Language Group1

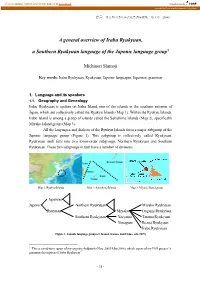

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Prometheus-Academic Collections 思言 東京外国語大学記述言語学論集 第 1 号(2006) A general overview of Irabu Ryukyuan, a Southern Ryukyuan language of the Japonic language group1 Michinori Shimoji Key words: Irabu Ryukyuan, Ryukyuan, Japonic languages, Japanese, grammar 1. Language and its speakers 1.1. Geography and Genealogy Irabu Ryukyuan is spoken on Irabu Island, one of the islands in the southern extreme of Japan, which are collectively called the Ryukyu Islands (Map 1). Within the Ryukyu Islands, Irabu Island is among a group of islands called the Sakishima Islands (Map 2), specifically Miyako Island group (Map 3). All the languages and dialects of the Ryukyu Islands form a major subgroup of the Japonic language group (Figure 1). This subgroup is collectively called Ryukyuan. Ryukyuan itself falls into two lower-order subgroups, Northern Ryukyuan and Southern Ryukyuan. These two subgroups in turn have a number of divisions. Map 1. Ryukyu Islands Map 2. Sakishima Islands Map 3. Miyako Island group Japanese Japonic Northern Ryukyuan Miyako Ryukyuan Ryuyuan Miyako Oogami Ryukyuan Southern Ryukyuan Yaeyama Tarama Ryukyuan Yonaguni Ikema Ryukyuan Irabu Ryukyuan Figure 1. Japonic language group (cf. Kamei, Koono, and Chino, eds. 1997) 1 This is a mid-term report of my ongoing fieldwork (Nov. 2005-May.2006), which is part of my PhD project “a grammar description of Irabu Ryukyuan”. - 31 - Michinori Shimoji 1.2. Previous studies on Irabu Ryukyuan The main focus of the previous studies on Irabu Ryukyuan has been on the phonetic/phonological aspects of that language. -

Affix Borrowing and Structural Borrowing in Japanese Word-Formation Akiko Nagano, Tohoku University Masaharu Shimada, University of Tsukuba

Affix borrowing and structural borrowing in Japanese word-formation Akiko Nagano, Tohoku University Masaharu Shimada, University of Tsukuba The wealth of English loanwords in the contemporary Japanese lexicon is well-known and constitutes a traditional research topic in Japanese linguistics. In contrast, there are very few previous studies that systematically investigate Japanese word-formation material and schemas copied from English. As a preliminary attempt to fill the gap, this paper examines the borrowing of three different English grammatical items: the adjectivalizing suffix -ic, the possessive pronoun my, and the preposition in. While the first case is affix-to-affix borrowing, the latter two cases are borrowing of grammatical words as word-formation items. First, -ic is borrowed as an adjectivalizing suffix, which, however, differs from the model in the type of adjectives produced. Next, the copy of my functions as a prefix that produces nouns with an anaphoric nature, which are reminiscent of self-N forms in English. The most complicated of the three are nominal modifiers involving the copying of in. In some cases, the model lends its surface form only; in other cases, its form and head-first structure are both replicated. To account for the qualitative mismatches between the donor model and recipient copy, the authors emphasize certain typological differences between the two languages involved. Keywords: language contact; English; Japanese; word-formation; grammatical borrowing; word syntax. 1. Introduction The topic of this paper is the influence of English on contemporary Japanese word formation and word syntax. Let us start with the lexicon. As succinctly introduced in Shibatani (1990: 140–157) and Hasegawa (2015: 61–74), the Japanese lexicon consists of native Japanese words, Sino-Japanese words, foreign words, and combinations of them. -

Chinese Letters and Intellectual Life in Medieval Japan: the Poetry and Political Philosophy of Chūgan Engetsu

Chinese Letters and Intellectual Life in Medieval Japan: The Poetry and Political Philosophy of Chūgan Engetsu By Brendan Arkell Morley A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Language in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor H. Mack Horton Professor Alan Tansman Professor Paula Varsano Professor Mary Elizabeth Berry Summer 2019 1 Abstract Chinese Letters and Intellectual Life in Medieval Japan: The Poetry and Political Philosophy of Chūgan Engetsu by Brendan Arkell Morley Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese University of California, Berkeley Professor H. Mack Horton, Chair This dissertation explores the writings of the fourteenth-century poet and intellectual Chūgan Engetsu 中巌円月, a leading figure in the literary movement known to history as Gozan (“Five Mountains”) literature. In terms of modern disciplinary divisions, Gozan literature straddles the interstices of several distinct areas of study, including classical Chinese poetry and poetics, Chinese philosophy and intellectual history, Buddhology, and the broader tradition of “Sinitic” poetry and prose (kanshibun) in Japan. Among the central contentions of this dissertation are the following: (1) that Chūgan was the most original Confucian thinker in pre-Tokugawa Japanese history, the significance of his contributions matched only by those of early-modern figures such as Ogyū Sorai, and (2) that kanshi and kanbun were creative media, not merely displays of erudition or scholastic mimicry. Chūgan’s expository writing demonstrates that the enormous multiplicity of terms and concepts animating the Chinese philosophical tradition were very much alive to premodern Japanese intellectuals, and that they were subject to thoughtful reinterpretation and application to specifically Japanese sociohistorical phenomena. -

The Function of English Loanwords in Japanese

The Function of English Loanwords in Japanese MARK REBUCK This paper examines the functions played by English loanwords in Japanese. It is shown that English loanwords have a role that extends far beyond the simple filling of lexical-gaps. Indeed, loanwords frequently take the place of an existing native equivalent where they perform a variety of “special effect” functions. In addition, English loanwords may be employed for euphemistic effect when a native equivalent is considered too direct. Drawing largely on examples of loanword use from advertising, this study considers the role English loanwords play as lexical gap fillers, special effect givers, and euphemisms. Introduction In recent years Japanese has seen a rapid increase in the number of words taken from other languages. The proliferation of these foreign borrowings is reflected in the number of entries for these words in major dictionaries. In 1967, for example, the Dictionary of Foreign Words, published by Kodakawa Shoten, listed 25,000 loanwords. By 1991, Sanseido’s Concise Dictionary of Foreign Words contained 33,500 loans, while the 2000 edition of Sanseido had further expanded to over 45,000 loanwords. Out of all these loanwords, or what the Japanese call gairaigo (外来語; lit. words which have come from outside), English loans are by far the most numerous, constituting approximately 90% of the total (Shinnouchi, 2000: 8). Drawing on numerous examples, particularly from Japanese print advertising1, this paper examines the major functions performed by these English loanwords. The Japanese Writing Systems To understand how the representation of English loanwords fits into the Japanese writing systems, it is helpful to have a basic knowledge of the overall system. -

Orthographic Representation and Variation Within the Japanese Writing System Some Corpus-Based Observations

John Benjamins Publishing Company This is a contribution from Written Language & Literacy 15:2 © 2012. John Benjamins Publishing Company This electronic file may not be altered in any way. The author(s) of this article is/are permitted to use this PDF file to generate printed copies to be used by way of offprints, for their personal use only. Permission is granted by the publishers to post this file on a closed server which is accessible to members (students and staff) only of the author’s/s’ institute, it is not permitted to post this PDF on the open internet. For any other use of this material prior written permission should be obtained from the publishers or through the Copyright Clearance Center (for USA: www.copyright.com). Please contact [email protected] or consult our website: www.benjamins.com Tables of Contents, abstracts and guidelines are available at www.benjamins.com Orthographic representation and variation within the Japanese writing system Some corpus-based observations Terry Joyce, Bor Hodošček & Kikuko Nishina Tama University / Tokyo Institute of Technology / Tokyo Institute of Technology, Japan Given its multi-scriptal nature, the Japanese writing system can potentially yield some important insights into the complex relationships that can exist between units of language and units of writing. This paper discusses some of the difficult issues surrounding the notions of orthographic representation and variation within the Japanese writing system, as seen from the perspective of creating word lists based on the Kokuritsu -

Japanese Kœ10 Syllabus

Japanese K–10 Syllabus June 2003 © 2003 Copyright Board of Studies NSW for and on behalf of the Crown in right of the State of New South Wales. This document contains Material prepared by the Board of Studies NSW for and on behalf of the State of New South Wales. The Material is protected by Crown copyright. All rights reserved. No part of the Material may be reproduced in Australia or in any other country by any process, electronic or otherwise, in any material form or transmitted to any other person or stored electronically in any form without the prior written permission of the Board of Studies NSW, except as permitted by the Copyright Act 1968. School students in NSW and teachers in schools in NSW may copy reasonable portions of the Material for the purposes of bona fide research or study. When you access the Material you agree: • to use the Material for information purposes only • to reproduce a single copy for personal bona fide study use only and not to reproduce any major extract or the entire Material without the prior permission of the Board of Studies NSW • to acknowledge that the Material is provided by the Board of Studies NSW • not to make any charge for providing the Material or any part of the Material to another person or in any way make commercial use of the Material without the prior written consent of the Board of Studies NSW and payment of the appropriate copyright fee • to include this copyright notice in any copy made • not to modify the Material or any part of the Material without the express prior written permission of the Board of Studies NSW. -

Uhm Phd 4271 R.Pdf

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I LIBRARY A RECONSTRUCTION OF THE ACCENTUAL HISTORY OF THE JAPANESE AND RYUKYUAN LANGUAGES A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS DECEMBER 2002 BY Moriyo Shimabukuro Dissertation Committee: Leon A. Serafim, Chairman Robert Blust Kenneth Rehg Patricia Donegan Robert Huey llJ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Looking back upon my life in Honolulu, I have realized how wonderful my life has been. Vivid memories come back as if I am turning pages of a picture album. People that I have met made my life here precious. My studies at the University of Hawai'i at Manoa have been very fruitful. Since the day I arrived, I have learned a great number of things about the Japonic languages from Leon A. Serafim, my advisor. I have really enjoyed myself being with him. This dissertation could not have been completed without his valuable comments, insightful suggestions, and encouragement. lowe him a great amount, especially his time and energy that he spent with me while I was writing my dissertation. To express my appreciation, I would like to say "Ippee nihwee deebiru." I would also like to thank my other committee members, Ken Rehg, Robert Blust, Patricia Donegan, and Robert Huey, for reading this dissertation and giving me insightful comments. I learned a lot from discussions with them. I am grateful to them for being on my committee. I would also like to express my gratitude to Alexander Vovin, who has taught me a lot in class and outside classrooms while I was at the university. -

Language Borrowing and the Indices of Adaptability and Receptivity

Intercultural Communication Studies XIV: 2 2005 Hoffer - Language Borrowing Language Borrowing and the Indices of Adaptability and Receptivity Bates L. Hoffer Trinity University Introduction One of the most easily observable results of intercultural contact and communication is the set of loanwords that is imported into the vocabulary of each language involved. The field of cultures and languages in contact (Weinreich 1953) has grown a great deal over the past fifty years. From the early studies, a 'Scale' or 'Index of Receptivity' has been posited for languages which more readily accept borrowings. Alongside that scale, a 'Scale of Adaptability' has been posited. The study of a language's adaptability and receptivity of borrowed words, especially those from International English, provides some interesting case studies. Major languages such as English, Spanish, Japanese and Chinese make good case studies for the discussion of the indices of adaptability and receptivity. Language Borrowing Processes Language borrowing has been an interest to various fields of linguistics for some time. (Whitney 1875, deSaussure 1915, Sapir 1921, Pedersen 1931, Haugen 1950, Lehmann 1962, Hockett 1979, Anttila 1989) In the study language borrowing, loanwords are only one of the types of borrowings that occur across language boundaries. The speakers of a language have various options when confronted with new items and ideas in another language. Hockett (1958) has organized the options as follows. (1) Loanword Speakers may adopt the item or idea and the source language word for each. The borrowed form is a Loanword. These forms now function in the usual grammatical processes, with nouns taking plural and/or possessive forms of the new language and with verbs and adjectives receiving native morphemes as well. -

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics Title Affectedness Constructions: How Languages Indicate Positive and Negative Events Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9fx1c060 Author Smith, Tomoko Publication Date 2005 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Affectedness Constructions: How languages indicate positive and negative events by Tomoko Yamashita Smith B.S. (Doshisha Women’s College) 1987 M.A. (San Jose State University) 1995 M.A. (University of California, Berkeley) 1997 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor Eve E. Sweetser Professor Soteria Svorou Professor Charles J. Fillmore Professor Yoko Hasegawa Fall 2005 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Affectedness Constructions: How languages indicate positive and negative events Copyright 2005 by Tomoko Yamashita Smith Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Abstract Affectedness constructions: How languages indicate positive and negative events by Tomoko Yamashita Smith Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Eve E. Sweetser, Chair This dissertation is a cross-linguistic study of what I call “affectedness constructions” (ACs) that express the notions of benefit and adversity. Since there is little research dealing with both benefactives and adversatives at the same time, the main goal of this dissertation is to establish AC as a grammatical category. First, many instances of ACs in the world are provided to show both the diversity of ACs and the consistent patterns among them. -

Altaic Languages

Altaic Languages Masaryk University Press Reviewed by Ivo T. Budil Václav Blažek in collaboration with Michal Schwarz and Ondřej Srba Altaic Languages History of research, survey, classification and a sketch of comparative grammar Masaryk University Press Brno 2019 Publication financed by the grant No. GA15-12215S of the Czech Science Foundation (GAČR) © 2019 Masaryk University Press ISBN 978-80-210-9321-8 ISBN 978-80-210-9322-5 (online : pdf) https://doi.org/10.5817/CZ.MUNI.M210-9322-2019 5 Analytical Contents 0. Preface .................................................................. 9 1. History of recognition of the Altaic languages ............................... 15 1.1. History of descriptive and comparative research of the Turkic languages ..........15 1.1.1. Beginning of description of the Turkic languages . .15 1.1.2. The beginning of Turkic comparative studies ...........................21 1.1.3. Old Turkic language and script – discovery and development of research .....22 1.1.4. Turkic etymological dictionaries .....................................23 1.1.5. Turkic comparative grammars .......................................24 1.1.6. Syntheses of grammatical descriptions of the Turkic languages .............25 1.2. History of descriptive and comparative research of the Mongolic languages .......28 1.2.0. Bibliographic survey of Mongolic linguistics ...........................28 1.2.1. Beginning of description of the Mongolic languages .....................28 1.2.2. Standard Mongolic grammars and dictionaries ..........................31 1.2.3. Mongolic comparative and etymological dictionaries .....................32 1.2.4. Mongolic comparative grammars and grammatical syntheses...............33 1.3. History of descriptive and comparative research of the Tungusic languages ........33 1.3.0. Bibliographic survey of the Tungusic linguistics.........................33 1.3.1. Beginning of description of the Tungusic languages ......................34 1.3.2.