Shakespeare Hamlet És Macbeth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View in Order to Answer Fortinbras’S Questions

SHAKESPEAREAN VARIATIONS: A CASE STUDY OF HAMLET, PRINCE OF DENMARK Steven Barrie A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2009 Committee: Dr. Stephannie S. Gearhart, Advisor Dr. Kimberly Coates ii ABSTRACT Dr. Stephannie S. Gearhart, Advisor In this thesis, I examine six adaptations of the narrative known primarily through William Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark to answer how so many versions of the same story can successfully exist at the same time. I use a homology proposed by Gary Bortolotti and Linda Hutcheon that explains there is a similar process behind cultural and biological adaptation. Drawing from the connection between literary adaptations and evolution developed by Bortolotti and Hutcheon, I argue there is also a connection between variation among literary adaptations of the same story and variation among species of the same organism. I determine that multiple adaptations of the same story can productively coexist during the same cultural moment if they vary enough to lessen the competition between them for an audience. iii For Pam. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Stephannie Gearhart, for being a patient listener when I came to her with hints of ideas for my thesis and, especially, for staying with me when I didn’t use half of them. Her guidance and advice have been absolutely essential to this project. I would also like to thank Kim Coates for her helpful feedback. She has made me much more aware of the clarity of my sentences than I ever thought possible. -

Performing Shakespeare in Contemporary Taiwan

Performing Shakespeare in Contemporary Taiwan by Ya-hui Huang A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire Jan 2012 Abstract Since the 1980s, Taiwan has been subjected to heavy foreign and global influences, leading to a marked erosion of its traditional cultural forms. Indigenous traditions have had to struggle to hold their own and to strike out into new territory, adopt or adapt to Western models. For most theatres in Taiwan, Shakespeare has inevitably served as a model to be imitated and a touchstone of quality. Such Taiwanese Shakespeare performances prove to be much more than merely a combination of Shakespeare and Taiwan, constituting a new fusion which shows Taiwan as hospitable to foreign influences and unafraid to modify them for its own purposes. Nonetheless, Shakespeare performances in contemporary Taiwan are not only a demonstration of hybridity of Westernisation but also Sinification influences. Since the 1945 Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party, or KMT) takeover of Taiwan, the KMT’s one-party state has established Chinese identity over a Taiwan identity by imposing cultural assimilation through such practices as the Mandarin-only policy during the Chinese Cultural Renaissance in Taiwan. Both Taiwan and Mainland China are on the margin of a “metropolitan bank of Shakespeare knowledge” (Orkin, 2005, p. 1), but it is this negotiation of identity that makes the Taiwanese interpretation of Shakespeare much different from that of a Mainlanders’ approach, while they share certain commonalities that inextricably link them. This study thus examines the interrelation between Taiwan and Mainland China operatic cultural forms and how negotiation of their different identities constitutes a singular different Taiwanese Shakespeare from Chinese Shakespeare. -

James Thurber

James Thurber The Macbeth murder mystery “It was a stupid mistake to make," said the American woman I had met at my hotel in the English lake country, “but it was on the counter with the other Penguin books - the little sixpenny ones, you know; with the paper covers - and 1 supposed of. course it was a detective story All the others were detective stories. I‟d read all the others, .So I bought this one without really looking at it carefully. You can imagine how mad I was when I found it was Shakespeare." I murmured something sympathetically." 1 don't see why the Penguin-books people had to get out Shakespeare plays in the sane size and everything as the detective stories," went on my companion. “I think they have different colored jackets," I said. "Well, I didn't notice that," she said. "Anyway, I got real comfy in bed that night and all ready to read a good mystery story and here I had 'The Tragedy of Macbeth” – a book for high school students. Like „Ivanhoe,‟” “Or „Lorne Doone.‟” I said.. "Exactly," said the American lady. "And I was just crazy for a good Agatha Christie, or something. Hercule Poirot is my favorite detective." “Is he the rabbity one?" I asked. "Oh, no," said my crime- fiction expert. "He's the Belgian one. You're thinking of Mr. Pinkerton, the one that helps Inspector Bull. He's good, too." Over her second cup of tea my companion began to tell the plot of a detective story that had fooled her completely - it seems it was the old family doctor all the time. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

Sources and Transmission of the Celtic Culture Trough the Shakespearean Repertory Celine Savatier-Lahondès

Transtextuality, (Re)sources and Transmission of the Celtic Culture Trough the Shakespearean Repertory Celine Savatier-Lahondès To cite this version: Celine Savatier-Lahondès. Transtextuality, (Re)sources and Transmission of the Celtic Culture Trough the Shakespearean Repertory. Linguistics. Université Clermont Auvergne; University of Stirling, 2019. English. NNT : 2019CLFAL012. tel-02439401 HAL Id: tel-02439401 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02439401 Submitted on 14 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. University of Stirling – Université Clermont Auvergne Transtextuality, (Re)sources and Transmission of the Celtic Culture Through the Shakespearean Repertory THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (PH.D) AND DOCTEUR DES UNIVERSITÉS (DOCTORAT) BY CÉLINE SAVATIER LAHONDÈS Co-supervised by: Professor Emeritus John Drakakis Professor Emeritus Danièle Berton-Charrière Department of Arts and Humanities IHRIM Clermont UMR 5317 University of Stirling Faculté de Lettres et Sciences -

(Non-)Sense in King Lear by Carolin Roder

Wissenschaftliches Seminar Online Deutsche Shakespeare-Gesellschaft Ausgabe 5 (2007) Shakespearean Soundscapes: Music – Voices – Noises – Silence www.shakespeare-gesellschaft.de/publikationen/seminar/ausgabe2007 Wissenschaftliches Seminar Online 5 (2007) HERAUSGEBER Das Wissenschaftliche Seminar Online wird im Auftrag der Deutschen Shakespeare-Gesellschaft, Sitz Weimar, herausgegeben von: Dr. Susanne Rupp, Universität Hamburg, Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik, Von-Melle-Park 6, D-20146 Hamburg ([email protected]) Prof. Dr. Tobias Döring, Institut für Englische Philologie, Schellingstraße 3 RG, D-80799 München ([email protected]) Dr. Jens Mittelbach, Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen, Platz der Göttinger Sieben 1, 37073 Göttingen ([email protected]) ERSCHEINUNGSWEISE Das Wissenschaftliche Seminar Online erscheint im Jahresrhythmus nach den Shakespeare-Tagen der Deutschen Shakespeare-Gesellschaft und enthält Beiträge der Wissenschaftler, die das Wissenschaftli- che Seminar zum Tagungsthema bestreiten. HINWEISE FÜR BEITRÄGER Beiträge für das Wissenschaftliche Seminar Online sollten nach den Richtlinien unseres Stilblattes formatiert sein. Bitte laden sie sich das Stilblatt als PDF-Datei von unserer Webseite herunter: http://www.shakespeare-gesellschaft.de/uploads/media/stilblatt_manuskripte.pdf Bitte senden Sie Ihren Beitrag in einem gebräuchlichen Textverarbeitungsformat an einen der drei Herausgeber. INTERNATIONAL STANDARD SERIAL NUMBER ISSN 1612-8362 © Copyright 2008 Deutsche -

1 Shakespeare and Film

Shakespeare and Film: A Bibliographic Index (from Film to Book) Jordi Sala-Lleal University of Girona [email protected] Research into film adaptation has increased very considerably over recent decades, a development that coincides with postmodern interest in cultural cross-overs, artistic hybrids or heterogeneous discourses about our world. Film adaptation of Shakespearian drama is at the forefront of this research: there are numerous general works and partial studies on the cinema that have grown out of the works of William Shakespeare. Many of these are very valuable and of great interest and, in effect, form a body of work that is hybrid and heterogeneous. It seems important, therefore, to be able to consult a detailed and extensive bibliography in this field, and this is the contribution that we offer here. This work aims to be of help to all researchers into Shakespearian film by providing a useful tool for ordering and clarifying the field. It is in the form of an index that relates the bibliographic items with the films of the Shakespearian corpus, going from the film to each of the citations and works that study it. Researchers in this field should find this of particular use since they will be able to see immediately where to find information on every one of the films relating to Shakespeare. Though this is the most important aspect, this work can be of use in other ways since it includes an ordered list of the most important contributions to research on the subject, and a second, extensive, list of films related to Shakespeare in order of their links to the various works of the canon. -

The Fantastic in Shakespeare: Hamlet and Macbeth

Odsjek za anglistiku Filozofski fakultet Sveučilište u Zagrebu The Fantastic in Shakespeare: Hamlet and Macbeth (Smjer: Engleska književnost i kultura) Kandidat: Petra Bušelić Mentor: dr. sc. Iva Polak Ak. godina: 2014./2015. Listopad, 2015. Contents 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 2. Todorov’s Theory of the Fantastic ..................................................................................... 2 3. Hamlet .................................................................................................................................... 7 3.1. “Who’s There”: Enter Fantastic Ghost ............................................................................ 8 3.2. Putting on the “Antic Disposition” ................................................................................ 15 3.3. The Ghost Comes in Such a Questionable Shape .......................................................... 19 4. Macbeth ............................................................................................................................... 22 4.1. The “Unreal Mock’ry” of Banquo’s Ghost ................................................................... 22 4.2. The Weird Sisters as Imperfect Speakers ...................................................................... 26 4.3. Kingship, Witchcraft and Jacobean Royal Ideology ..................................................... 32 5. Shakespeare’s Dramatic Use of the Supernatural ......................................................... -

Hamlet, the Ghost and the Model Reader

HAMLET, THE GHOST AND THE MODEL READER THE PROBLEMS OF THE RECEPTION AND A CONCEPT OF SHAKESPEARE’S HAMLET Doctoral dissertation by András G. Bernáth Supervisor: Prof. Guido Latré, PhD Université Catholique de Louvain 2013 ABSTRACT In a comprehensive study of Hamlet and its reception, this dissertation offers a concept and interpretation of Shakespeare’s work as a complex literary work and play for the theatre. It is argued that the play, through a series of ambiguities, implies two main levels of meaning, which complement each other in a truly dramatic contrast, exploring the main theme of Hamlet and dramatic art in general: seeming and being, or illusion and reality. On the surface, which has been usually maintained since the Restoration, Hamlet seems to be a moral hero, who “sets it right” by punishing the evil villain, the usurper King Claudius, following the miraculous return of the murdered King Hamlet from the dead. At a deeper level, exploring the Christian context including King James’s Daemonologie (1597), the Ghost demanding revenge is, in fact, a disguised devil, exploiting the tragic flaw of the protagonist, who wishes the damnation of his enemy. Fortinbras, who comes from the north like King James and renounces revenge, is rewarded with the kingdom after the avengers, Hamlet and Laertes, kill each other and virtually the entire Danish court is wiped out through Hamlet’s quest of total revenge, pursuing both body and soul. The aesthetic identity of Hamlet is also examined. In addition to the mainly philological and historical analysis of the text, the play, some adaptations and the critical reception, theoretical concerns are also included. -

The Tragedy of Macbeth, Act 3.3 and 3.4, Lines 1-41

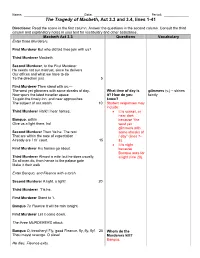

Name: __________________________________Date: _______________________________ Period: ______________ The Tragedy of Macbeth, Act 3.3 and 3.4, lines 1-41 Directions: Read the scene in the first column. Answer the questions in the second column. Consult the third column and explanatory notes in your text for vocabulary and other assistance. Macbeth Act 3.3 Questions Vocabulary Enter three Murderers First Murderer But who did bid thee join with us? Third Murderer Macbeth. Second Murderer, to the First Murderer He needs not our mistrust, since he delivers Our offices and what we have to do To the direction just. 5 First Murderer Then stand with us.— The west yet glimmers with some streaks of day. What time of day is glimmers (v.) – shines Now spurs the lated traveller apace it? How do you faintly To gain the timely inn, and near approaches know? The subject of our watch. 10 Student responses may include: Third Murderer Hark! I hear horses. It is sunset, or near dark Banquo, within because “the Give us a light there, ho! west yet glimmers with Second Murderer Then 'tis he. The rest some streaks of That are within the note of expectation / day” (lines 7– Already are i' th’ court. 15 8). It is night First Murderer His horses go about. because Banquo asks for Third Murderer Almost a mile: but he does usually, a light (line 20). So all men do, from hence to the palace gate Make it their walk. Enter Banquo, and Fleance with a torch. Second Murderer A light, a light! 20 Third Murderer 'Tis he. -

A Poetics of Ghosting in Contemporary Irish and Northern Irish Drama

A Poetics of Ghosting in Contemporary Irish and Northern Irish Drama A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Mary Katherine Martinovich IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. Margaret Werry Advisor April 2012 © Kay Martinovich, April 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My sincerest gratitude must be extended to those people who were with me as I traveled on this extraordinary journey of writing about Ireland’s ghosts. To my advisor, Margaret Werry: for her persistent support that was also a source of inspiration as I revised and refined every step of the way. She was the colleague in my corner (reading draft upon draft) as well as the editor extraordinaire who taught me so much about the process itself. She offered unyielding guidance with great wisdom, clarity, and compassion. Go raibh míle maith agat as chuile shórt. Tá tú ar fheabhas! To my committee members Michal Kobialka, Sonja Kuftinec, and Mary Trotter: Michal gave me an incredible piece of encouragement just when I needed it – I thank him for his insightful feedback and commitment to my project. Sonja’s positive spirit also energized me at just the right time. Her comments were always invaluable and oh so supportive – I thank her profusely. From the beginning, Mary has been an enthusiastic advocate for me and for my work. With her vast knowledge of Irish theatre, I have been quite fortunate to have her on my side – my heartfelt thanks to her. To my friends Vivian Wang, Kathleen Andrade, Maggie Scanlan, Matt O’Brien, James S. -

1 Name___KEY___Date___Macbeth: Act III Reading and Study Guide I. Vocabulary

Name______KEY_________ Date_____________ Macbeth: Act III Reading and Study Guide I. Vocabulary: Be able to define the following words and understand them when they appear in the play. Also, be prepared to be quizzed on these words. posterity: future generations cide: kill (Shakespeare uses parricide, which means the act of killing one’s parents.) Also, think about regicide, patricide, matricide naught: nothing jovial: jolly; cheerful muse: to think about in silence mirth: joy ruby: red blanch: turn pale white wayward: turned away (perverted) from what is the expected norm; resistant to guidance or discipline II. Background Info: Mark Antony & Octavius (Augustus) Caesar: after Julius Caesar was assassinated, Antony and Octavius joined forces to defeat Cassius and Brutus (co-conspirators in the assassination of Julius Caesar). The two joined forces with a third man (Lepidus) to rule Rome. Accounts have Antony and Octavius being friends early on, but later Octavius turns on Antony and defeats him to take supreme rule of Rome. Acheron: a river in Hades (underworld) over which the souls of the dead were ferried. Similar to Styx. The word often comes to represent Hades altogether. The dictionary defines it as hell. In Dante’s Inferno, the river borders hell. III. Literary Terms: these will be the terms that we use to discuss this act. Please know them for our discussion and your tests and quizzes. apostrophe: (Etymology = apo [away] + strophe [turn]) When a character makes an apostrophe, or apostrophizes, that character turns away and speaks to nothing. They may speak to someone who is absent, dead, or something that is not human, e.g., Fate.