The Paradox of Localism Exploring Rhetoric and Reform Promoting the Devolution of Power, from 1964 to 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Red Book

The For this agenda-setting collection, the leading civil society umbrella groups ACEVO and CAF worked with Lisa Nandy MP to showcase some of Red Book Labour’s key thinkers about the party’s future relationship with charities The and social enterprises. The accompanying ‘Blue Book’ and ‘Yellow Book’ feature similar essays from the Conservative and Liberal Democrat Parties. ‘This collection of essays shows the depth and vibrancy of thinking across the Labour movement on this important issue and makes a vital the Voluntary of Sector Red Book contribution to the debate in the run-up to the next election.’ Rt Hon Ed Miliband MP, Leader of the Labour Party of the ‘I hope this collection will be a provocation to further dialogue with Labour and with all the major political parties. It demonstrates a willingness to listen … that our sector should be grateful for.’ Voluntary Sector Sir Stephen Bubb, Chief Executive, ACEVO ‘The contributions in this collection show that the Labour Party possesses exciting ideas and innovations designed to strengthen Britain’s charities, Civil Society and the Labour Party and many of the concepts explored will be of interest to whichever party (or parties) are successful at the next election.’ after the 2015 election Dr John Low CBE, Chief Executive, Charities Aid Foundation With a foreword by the Rt Hon Ed Miliband MP £20 ISBN 978-1-900685-70-2 9 781900 685702 acevo-red-book-cover-centred-spine-text.indd All Pages 05/09/2014 15:40:12 The Red Book of the Voluntary Sector Civil Society and the Labour Party after -

Cooperative Localism: Federal-Local Collaboration in an Era of State Sovereignty

DAVIDSON_BOOK 5/17/2007 5:10 PM COOPERATIVE LOCALISM: FEDERAL-LOCAL COLLABORATION IN AN ERA OF STATE SOVEREIGNTY Nestor M. Davidson* INTRODUCTION................................................................................... 960 I. BACKGROUND: FEDERAL-LOCAL COOPERATION AND CONSTITUTIONAL STRUCTURE................................................... 964 A. The Importance of Direct Federal-Local Cooperation...... 966 B. Local Autonomy and the Intermediary of the States.......... 975 II. LOCAL GOVERNMENT POWERLESSNESS AND STATE SOVEREIGNTY .............................................................................. 979 A. Plenary State Control of Local Governments and the Unitary State........................................................................... 980 B. Modern Federalism, State Sovereignty, and Local Governments.......................................................................... 984 III. THE TRADITION OF FEDERAL EMPOWERMENT OF LOCAL GOVERNMENTS ............................................................................ 990 A. Cracks in the Façade of the Unitary State............................ 991 1. Local Disaggregation from the States............................ 991 2. Shadow Constitutional Protection for Local Autonomy ........................................................................ 994 B. Federal Empowerment of Local Governments .................. 995 1. Autonomy and the Authority to Act.............................. 996 2. Fiscal Federalism, Local Spending, and State Interference ..................................................................... -

House of Commons Official Report Parliamentary Debates

Monday Volume 652 7 January 2019 No. 228 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 7 January 2019 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2019 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. HER MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT MEMBERS OF THE CABINET (FORMED BY THE RT HON. THERESA MAY, MP, JUNE 2017) PRIME MINISTER,FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY AND MINISTER FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE—The Rt Hon. Theresa May, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE DUCHY OF LANCASTER AND MINISTER FOR THE CABINET OFFICE—The Rt Hon. David Lidington, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER—The Rt Hon. Philip Hammond, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT—The Rt Hon. Sajid Javid, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH AFFAIRS—The Rt. Hon Jeremy Hunt, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EXITING THE EUROPEAN UNION—The Rt Hon. Stephen Barclay, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE—The Rt Hon. Gavin Williamson, MP LORD CHANCELLOR AND SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE—The Rt Hon. David Gauke, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE—The Rt Hon. Matt Hancock, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR BUSINESS,ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY—The Rt Hon. Greg Clark, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF TRADE—The Rt Hon. Liam Fox, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS—The Rt Hon. Amber Rudd, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION—The Rt Hon. Damian Hinds, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR ENVIRONMENT,FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS—The Rt Hon. -

Announcement

Announcement Total 100 articles, created at 2016-07-09 18:01 1 Wimbledon: Serena Williams eyes revenge against Angelique Kerber in today's final (1.14/2) Serena Williams has history in her sights as the defending champion plots to avenge one of the most painful defeats of her career by beating Angelique Kerber in today’s Wimbledon final 2016-07-09 14:37 1KB www.mid-day.com 2 Phoenix police use tear gas on Black Lives Matter rally (PHOTOS, VIDEOS) — RT America (1.03/2) Police have used pepper spray during a civil rights rally in Phoenix, Arizona, late on Friday night. The use of impact munitions didn’t lead to any injuries, and no arrests have been made, Phoenix Police Chief said. 2016-07-09 18:00 1KB www.rt.com 3 Castile would be alive today if he were white: Minnesota Governor (1.02/2) A county prosecutor investigating the police shooting of a black motorist in Minnesota on Friday said law enforcement authorities in his state and nationwide must improve practices and procedures to prevent future such tragedies, regardless of the outcome of his probe. 2016-07-09 18:00 3KB www.timeslive.co.za 4 Thousands take to streets across US to protest police violence (1.02/2) Thousands of people took to the streets in US cities on Friday to denounce the fatal police shootings of two black men this week, marching the day after a gunman killed five police officers watching over a similar demonstration in Dallas. 2016-07-09 18:00 3KB www.timeslive.co.za 5 Iran says it will continue its ballistic missile program (1.02/2) TEHRAN, Iran—Iran says it will continue its ballistic missile program after claims made by the UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon that its missile tests aren't in the spirit of the 2016-07-09 17:37 1KB newsinfo.inquirer.net 6 Hillary Clinton reacts to Dallas shootings In an interview with Scott Pelley that aired first on CBSN, Hillary (1.02/2) Clinton shared her thoughts on Thursday's shooting in Dallas. -

Participatory Economics & the Next System

Created by Matt Caisley from the Noun Project Participatory Economics & the Next System By Robin Hahnel Introduction It is increasingly apparent that neoliberal capitalism is not working well for most of us. Grow- ing inequality of wealth and income is putting the famous American middle class in danger of becoming a distant memory as American children, for the first time in our history, now face economic prospects worse than what their parents enjoyed. We suffer from more frequent financial “shocks” and linger in recession far longer than in the past. Education and health care systems are being decimated. And if all this were not enough, environmental destruction continues to escalate as we stand on the verge of triggering irreversible, and perhaps cataclys- mic, climate change. yst w s em p e s n s o l s a s i s b o i l p iCreated by Matt Caisley o fromt the Noun Project r ie s & p However, in the midst of escalating economic dysfunction, new economic initia- tives are sprouting up everywhere. What these diverse “new” or “future” economy initiatives have in common is that they reject the economics of competition and greed and aspire instead to develop an economics of equitable cooperation that is environmentally sustainable. What they also have in common is that they must survive in a hostile economic environment.1 Helping these exciting and hopeful future economic initiatives grow and stay true to their principles will require us to think more clearly about what kind of “next system” these initiatives point toward. It is in this spirit -

Wellbeing in Four Policy Areas

Wellbeing in four policy areas Report by the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Wellbeing Economics September 2014 The All Party Parliamentary Group on Wellbeing Economics was set up to: • Provide a forum for discussion of wellbeing issues and public policy in Parliament • Promote enhancement of wellbeing as an important government goal • Encourage the adoption of wellbeing indicators as complimentary measures of progress to GDP • Promote policies designed to enhance wellbeing. The New Economics Foundation (NEF) provides the secretariat to the group. Contents Foreword 2 Summary 3 1. Introduction: Scope of the inquiry 9 2. A wellbeing approach to policy: What it means and why it matters 10 3. Building a high wellbeing economy: Labour market policy 18 4. Building high wellbeing places: Planning and transport policy 24 5. Building personal resources: Mindfulness in health and education 30 6. Valuing what matters: Arts and culture policy 36 7. Conclusion 42 Appendix: List of expert witnesses 43 References 45 2 DiversityWellbeing and in fourIntegration policy areas Foreword It is now eight years since David Cameron first declared: ‘it’s time we focused not just on GDP, but on GWB – general wellbeing’,1 and five years since the influential Commission on the Measurement of Progress, chaired by Joseph Stiglitz, argued that we need to ‘shift emphasis from measuring economic production to measuring people’s wellbeing’.2 As we near the end of the first parliament in which the UK has begun systematically measuring national wellbeing – becoming a global leader in the process – now is a timely moment to take stock of this agenda and ask what needs to happen next. -

OPENING PANDORA's BOX David Cameron's Referendum Gamble On

OPENING PANDORA’S BOX David Cameron’s Referendum Gamble on EU Membership Credit: The Economist. By Christina Hull Yale University Department of Political Science Adviser: Jolyon Howorth April 21, 2014 Abstract This essay examines the driving factors behind UK Prime Minister David Cameron’s decision to call a referendum if the Conservative Party is re-elected in 2015. It addresses the persistence of Euroskepticism in the United Kingdom and the tendency of Euroskeptics to generate intra-party conflict that often has dire consequences for Prime Ministers. Through an analysis of the relative impact of political strategy, the power of the media, and British public opinion, the essay argues that addressing party management and electoral concerns has been the primary influence on David Cameron’s decision and contends that Cameron has unwittingly unleashed a Pandora’s box that could pave the way for a British exit from the European Union. Acknowledgments First, I would like to thank the Bates Summer Research Fellowship, without which I would not have had the opportunity to complete my research in London. To Professor Peter Swenson and the members of The Senior Colloquium, Gabe Botelho, Josh Kalla, Gabe Levine, Mary Shi, and Joel Sircus, who provided excellent advice and criticism. To Professor David Cameron, without whom I never would have discovered my interest in European politics. To David Fayngor, who flew halfway across the world to keep me company during my summer research. To my mom for her unwavering support and my dad for his careful proofreading. And finally, to my adviser Professor Jolyon Howorth, who worked with me on this project for over a year and a half. -

Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures Bill Committee Stage Report Bill 211 2010-12 RESEARCH PAPER 11/62 24 August 2011

Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures Bill Committee Stage Report Bill 211 2010-12 RESEARCH PAPER 11/62 24 August 2011 This is a report on the House of Commons Committee Stage of the Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures Bill. It complements Research Paper 11/46 prepared for the Commons Second Reading. Report Stage and Third Reading are scheduled for 5 September 2011. Significant areas of debate at Committee Stage included: the lack of a legal definition for overnight residence requirements that could be imposed on suspects; the fact that the Home Secretary would no longer be able to geographically relocate terror suspects; proposals to allow suspects access to a mobile phone and computer. Some Members expressed a particular worry about the inability to renew measures imposed on suspects after two years, unless there was evidence of new terrorism-related activity. Only a small series of Government amendments, which were mostly described as drafting or technical amendments, were made in Committee. One of these extended certain provisions (relating to devolved matters) to Scotland with the agreement of the Scottish Government. Alexander Horne Recent Research Papers 11/52 Pensions Bill [HL] [Bill 183 of 2010-12] 16.06.11 11/53 Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Bill [Bill 205 of 2010- 27.06.11 12] 11/54 Protection of Freedoms Bill: Committee Stage Report 28.06.11 11/55 Economic Indicators, July 2011 05.07.11 11/56 Police (Detention and Bail) Bill [Bill 216 of 2010-12] 05.07.11 11/57 Sovereign Grant Bill -

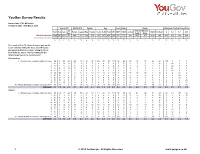

Survey Report

YouGov Survey Results Sample Size: 1703 GB Adults Fieldwork: 25th - 26th March 2019 Vote in 2017 EU Ref 2016 Gender Age Social Grade Region Likelihood of voting Conservative Lib Rest of Midlands / Total Con Lab Remain Leave Male Female 18-24 25-49 50-64 65+ ABC1 C2DE London North Scotland 0 1-4 5-7 8-10 Dem South Wales Weighted Sample 1703 562 526 95 656 702 824 879 187 717 405 393 971 732 204 569 368 416 146 640 303 342 419 Unweighted Sample 1703 619 526 110 737 720 766 937 148 684 447 424 1012 691 174 615 373 399 142 622 294 327 460 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 means you would never consider voting for them, and 10 means you would definitely consider voting for them, how likely are you to consider voting for the following parties at the next election? Conservative 0 - Would never consider voting for them 38 8 58 40 45 26 38 37 45 40 39 27 36 40 35 33 37 44 42 100 0 0 0 1 6 2 9 12 7 4 7 5 3 8 5 3 5 7 4 7 4 6 9 0 32 0 0 2 5 1 6 11 6 3 5 5 7 5 5 4 5 6 7 4 5 5 6 0 28 0 0 3 4 2 6 10 5 3 4 3 7 4 3 3 4 3 5 4 3 4 4 0 21 0 0 4 3 2 3 2 3 3 3 3 5 4 3 2 3 3 3 3 5 2 3 0 19 0 0 5 10 10 8 6 8 11 8 13 10 11 9 10 9 12 15 10 10 8 13 0 0 52 0 6 4 4 5 5 3 7 5 4 7 5 4 3 5 4 6 4 5 4 3 0 0 22 0 7 5 11 2 4 5 7 6 5 3 5 6 6 5 5 5 5 6 6 2 0 0 26 0 8 5 10 1 4 4 8 5 5 1 5 7 5 6 4 3 6 4 5 5 0 0 0 20 9 3 7 0 3 2 4 3 3 3 2 3 5 4 2 4 4 2 2 3 0 0 0 12 10 - Would definitely consider voting for them 17 44 2 4 12 26 16 18 7 11 16 33 19 14 11 21 17 15 11 0 0 0 68 AVERAGE 3.9 7.5 1.6 2.6 3.1 5.4 3.8 4.1 2.8 3.3 3.9 5.5 4.2 3.5 -

Policy Briefing

2015 Issue 3 (Publ. June 1) Vol. 9 Issue 3 A round up of policy events and news 1. Top story - General Election & Queen’s Speech Queen’s Speech – New legislative programme The Queen’s Speech sets out the Government’s legislative agenda, which this year consists of twenty six Bills. The first Conservative Queen’s Speech since 1996 contains few surprises as the proposed legislation reflects the Conservative’s pre-election manifesto commitments, such as a referendum on the UK’s membership of the EU, no rises in national insurance, income tax or VAT over the next five years, and extending Right to Buy to housing association tenants. There are four constitutional Bills devolving power away from Westminster. A consultation will be held on the move to replace the Human Rights Act with a British Bill of Rights. Bills of interest include: Scotland Bill This Bill will deliver, in full, the Smith Commission agreement on further devolution to Holyrood, including responsibility for setting levels of income tax. European Referendum Bill The EU referendum was a key part of the Conservative’s election campaign and this Bill will provide for a referendum of Britain’s membership of the EU. The vote will take place before the end of 2017. Enterprise Bill The Enterprise Bill seeks to cut business regulation and enable easier resolution of disputes for small businesses. Bank of England Bill The purpose of the Bill is to strengthen further the governance and accountability of the Bank of England to ensure it is well-positioned to oversee monetary policy and financial stability. -

The Capitalisation of Business Rates: an Empirical Study of Tax Incidence in Six London Boroughs

THE CAPITALISATION OF BUSINESS RATES: AN EMPIRICAL STUDY OF TAX INCIDENCE IN SIX LONDON BOROUGHS Nigel Mehdi Submitted for the Degree of PhD London School of Economics & Political Science 2003 1 UMI Number: U615607 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615607 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 SJbZlOl Z9 d SZZIH l Abstract THE CAPITALISATION OF BUSINESS RATES: AN EMPIRICAL STUDY OF TAX INCIDENCE IN SIX LONDON BOROUGHS ABSTRACT This work is concerned with tax shifting and capitalisation of recurrent taxes on immovable property, known as business rates in the United Kingdom and payable by occupiers of business property. The empirical research seeks to identify to what extent business rates are transferred into rents and thus capitalised. If the tax is capitalised, then freehold owners will bear the burden of the tax. If not, the tax may be shifted in some other way, for example, reducing the occupiers’ profits or increasing the prices charged to customers. The extent of any tax shifting will be affected by the value of any benefits received by the occupier in exchange for the tax paid. -

A Schema of Right-Wing Extremism in the United States

ICCT Policy Brief October 2019 DOI: 10.19165/2019.2.06 ISSN: 2468-0486 A Schema of Right-Wing Extremism in the United States Author: Sam Jackson Over the past two years, and in the wake of deadly attacks in Charlottesville and Pittsburgh, attention paid to right-wing extremism in the United States has grown. Most of this attention focuses on racist extremism, overlooking other forms of right-wing extremism. This article presents a schema of three main forms of right-wing extremism in the United States in order to more clearly understand the landscape: racist extremism, nativist extremism, and anti-government extremism. Additionally, it describes the two primary subcategories of anti-government extremism: the patriot/militia movement and sovereign citizens. Finally, it discusses whether this schema can be applied to right-wing extremism in non-U.S. contexts. Key words: right-wing extremism, racism, nativism, anti-government A Schema of Right-Wing Extremism in the United States Introduction Since the public emergence of the so-called “alt-right” in the United States—seen most dramatically at the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017—there has been increasing attention paid to right-wing extremism (RWE) in the United States, particularly racist right-wing extremism.1 Violent incidents like Robert Bowers’ attack on the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in October 2018; the mosque shooting in Christchurch, New Zealand in March 2019; and the mass shooting at a Walmart in El Paso, Texas in August