Unity, Vision and Brexit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

House of Commons Official Report Parliamentary Debates

Monday Volume 652 7 January 2019 No. 228 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 7 January 2019 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2019 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. HER MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT MEMBERS OF THE CABINET (FORMED BY THE RT HON. THERESA MAY, MP, JUNE 2017) PRIME MINISTER,FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY AND MINISTER FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE—The Rt Hon. Theresa May, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE DUCHY OF LANCASTER AND MINISTER FOR THE CABINET OFFICE—The Rt Hon. David Lidington, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER—The Rt Hon. Philip Hammond, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT—The Rt Hon. Sajid Javid, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH AFFAIRS—The Rt. Hon Jeremy Hunt, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EXITING THE EUROPEAN UNION—The Rt Hon. Stephen Barclay, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE—The Rt Hon. Gavin Williamson, MP LORD CHANCELLOR AND SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE—The Rt Hon. David Gauke, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE—The Rt Hon. Matt Hancock, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR BUSINESS,ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY—The Rt Hon. Greg Clark, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF TRADE—The Rt Hon. Liam Fox, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS—The Rt Hon. Amber Rudd, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION—The Rt Hon. Damian Hinds, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR ENVIRONMENT,FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS—The Rt Hon. -

Announcement

Announcement Total 100 articles, created at 2016-07-09 18:01 1 Wimbledon: Serena Williams eyes revenge against Angelique Kerber in today's final (1.14/2) Serena Williams has history in her sights as the defending champion plots to avenge one of the most painful defeats of her career by beating Angelique Kerber in today’s Wimbledon final 2016-07-09 14:37 1KB www.mid-day.com 2 Phoenix police use tear gas on Black Lives Matter rally (PHOTOS, VIDEOS) — RT America (1.03/2) Police have used pepper spray during a civil rights rally in Phoenix, Arizona, late on Friday night. The use of impact munitions didn’t lead to any injuries, and no arrests have been made, Phoenix Police Chief said. 2016-07-09 18:00 1KB www.rt.com 3 Castile would be alive today if he were white: Minnesota Governor (1.02/2) A county prosecutor investigating the police shooting of a black motorist in Minnesota on Friday said law enforcement authorities in his state and nationwide must improve practices and procedures to prevent future such tragedies, regardless of the outcome of his probe. 2016-07-09 18:00 3KB www.timeslive.co.za 4 Thousands take to streets across US to protest police violence (1.02/2) Thousands of people took to the streets in US cities on Friday to denounce the fatal police shootings of two black men this week, marching the day after a gunman killed five police officers watching over a similar demonstration in Dallas. 2016-07-09 18:00 3KB www.timeslive.co.za 5 Iran says it will continue its ballistic missile program (1.02/2) TEHRAN, Iran—Iran says it will continue its ballistic missile program after claims made by the UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon that its missile tests aren't in the spirit of the 2016-07-09 17:37 1KB newsinfo.inquirer.net 6 Hillary Clinton reacts to Dallas shootings In an interview with Scott Pelley that aired first on CBSN, Hillary (1.02/2) Clinton shared her thoughts on Thursday's shooting in Dallas. -

Survey Report

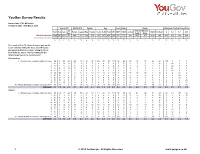

YouGov Survey Results Sample Size: 1703 GB Adults Fieldwork: 25th - 26th March 2019 Vote in 2017 EU Ref 2016 Gender Age Social Grade Region Likelihood of voting Conservative Lib Rest of Midlands / Total Con Lab Remain Leave Male Female 18-24 25-49 50-64 65+ ABC1 C2DE London North Scotland 0 1-4 5-7 8-10 Dem South Wales Weighted Sample 1703 562 526 95 656 702 824 879 187 717 405 393 971 732 204 569 368 416 146 640 303 342 419 Unweighted Sample 1703 619 526 110 737 720 766 937 148 684 447 424 1012 691 174 615 373 399 142 622 294 327 460 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 means you would never consider voting for them, and 10 means you would definitely consider voting for them, how likely are you to consider voting for the following parties at the next election? Conservative 0 - Would never consider voting for them 38 8 58 40 45 26 38 37 45 40 39 27 36 40 35 33 37 44 42 100 0 0 0 1 6 2 9 12 7 4 7 5 3 8 5 3 5 7 4 7 4 6 9 0 32 0 0 2 5 1 6 11 6 3 5 5 7 5 5 4 5 6 7 4 5 5 6 0 28 0 0 3 4 2 6 10 5 3 4 3 7 4 3 3 4 3 5 4 3 4 4 0 21 0 0 4 3 2 3 2 3 3 3 3 5 4 3 2 3 3 3 3 5 2 3 0 19 0 0 5 10 10 8 6 8 11 8 13 10 11 9 10 9 12 15 10 10 8 13 0 0 52 0 6 4 4 5 5 3 7 5 4 7 5 4 3 5 4 6 4 5 4 3 0 0 22 0 7 5 11 2 4 5 7 6 5 3 5 6 6 5 5 5 5 6 6 2 0 0 26 0 8 5 10 1 4 4 8 5 5 1 5 7 5 6 4 3 6 4 5 5 0 0 0 20 9 3 7 0 3 2 4 3 3 3 2 3 5 4 2 4 4 2 2 3 0 0 0 12 10 - Would definitely consider voting for them 17 44 2 4 12 26 16 18 7 11 16 33 19 14 11 21 17 15 11 0 0 0 68 AVERAGE 3.9 7.5 1.6 2.6 3.1 5.4 3.8 4.1 2.8 3.3 3.9 5.5 4.2 3.5 -

The Best Start for Life

The Best Start for Life A Vision for the 1,001 Critical Days The Early Years Healthy Development Review Report CP 419 The Best Start for Life A Vision for the 1,001 Critical Days The Early Years Healthy Development Review Report Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care by Command of Her Majesty March 2021 CP 419 The Best Start for Life © Crown copyright 2021 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/ version/3. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/official-documents. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] ISBN 978-1-5286-2497-8 CCS0321149360 03/21 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. 2 The Best Start for Life Contents Executive summary 7 Context 10 Why the 1,001 critical days are critical 13 The ways we already support families with babies 21 A summary of the Review’s areas for action 34 Action Area 1: Seamless support for new families 41 Action Area 2: A welcoming Hub for the family 63 Action Area 3: The information families need when they need it 82 Action Area 4: An empowered Start for Life workforce 91 Action Area 5: Continually improving the Start for Life offer 101 Action Area 6: Leadership for change 111 Annexes and endnotes 126 3 The Best Start for Life Foreword by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care I have always recognised the importance of the early years and the difference this period can make in achieving better physical and emotional health outcomes. -

Recall of Mps

House of Commons Political and Constitutional Reform Committee Recall of MPs First Report of Session 2012–13 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 21 June 2012 HC 373 [incorporating HC 1758-i-iv, Session 2010-12] Published on 28 June 2012 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Political and Constitutional Reform Committee The Political and Constitutional Reform Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to consider political and constitutional reform. Current membership Mr Graham Allen MP (Labour, Nottingham North) (Chair) Mr Christopher Chope MP (Conservative, Christchurch) Paul Flynn MP (Labour, Newport West) Sheila Gilmore MP (Labour, Edinburgh East) Andrew Griffiths MP (Conservative, Burton) Fabian Hamilton MP (Labour, Leeds North East) Simon Hart MP (Conservative, Camarthen West and South Pembrokeshire) Tristram Hunt MP (Labour, Stoke on Trent Central) Mrs Eleanor Laing MP (Conservative, Epping Forest) Mr Andrew Turner MP (Conservative, Isle of Wight) Stephen Williams MP (Liberal Democrat, Bristol West) Powers The Committee’s powers are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in Temporary Standing Order (Political and Constitutional Reform Committee). These are available on the Internet via http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm/cmstords.htm. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the internet at www.parliament.uk/pcrc. A list of Reports of the Committee in the present Parliament is at the back of this volume. -

Standard Note: SN07012 Last Updated: 30 March 2015

Progress of the Recall of MPs Bill 2014-15 Standard Note: SN07012 Last updated: 30 March 2015 Author: Isobel White and Richard Kelly Section Parliament and Constitution Centre The Recall of MPs Bill 2014-15 received Royal Assent on 26 March 2015. The Bill was introduced on 11 September 2014 and had its second reading on 21 October 2014. The committee stage of the Bill took place on the floor of the House of Commons over two days; the first committee stage debate was on 27 October 2014 and the second was on 3 November 2014. Zac Goldsmith tabled a number of amendments that would have replaced the Government’s system of recall, triggered by a MP’s conduct, with a system that allowed voters to initiate a recall process. The amendment was pressed and was defeated on a division. The only Government amendments made to the Bill were amendments to clarify the provisions of Clause 19 relating to the role of the Speaker in the recall process. These amendments were agreed on the second day of committee. At report stage on 24 November 2014 three Opposition amendments were agreed, these were To reduce the period of suspension from the House from 21 to 10 sitting days to trigger a recall; To make provision for a further recall condition of a Member being convicted of an offence under Section 10 of the Parliamentary Standards Act 2009; To pave the way to allow a recall petition to be triggered by an offence committed before the day Clause 1 comes into force. -

How Andrea Leadsom Could Have Avoided the Debate About Her Times Interview

This is the newspaper article at the centre of the furore Jul 09, 2016 20:58 +08 How Andrea Leadsom could have avoided the debate about her Times interview Do parents make better government leaders than childless people? This question has become a big source of embarassment for Andrea Leadsom, who is competing with Theresa May to lead the Conservative Party and become the United Kingdom's Prime Minister after David Cameron steps down. At issue is a newspaper interview with the London Times, in which she suggested that being a mother made her more qualified than the childless May. "I feel being a mum means you have a very real stake in the future of our country, a tangible stake," she is quoted as saying. When the article was published, she was incensed, saying in a tweet: Truly appalling and the exact opposite of what I said. I am disgusted. https://t.co/DPFzjNmKie — Andrea Leadsom MP (@andrealeadsom) July 8, 2016 Journalist Rachel Sylvester defended the article in an interview with the BBC, saying that "...the article was 'fairly written up' and she was 'baffled' by Mrs Leadsom's 'rather aggressive reaction'." (full article under Links) Times Deputy Editor Emma Tucker tweeted the relevant part of the transcript: Transcript from the key part of the interview with Andrea Leadsom this morning in @thetimespic.twitter.com/aFtIECBIiC — Emma Tucker (@emmatimes2) July 8, 2016 David Cameron weighed in with his own tongue-in-cheque assessment: I'm disgusted that Andrea #Leadsom has been reported saying exactly what she actually said. Shoddy journalism. -

Parliamentary Conventions

REPORT Parliamentary Conventions Jacqy Sharpe About the Author Jacqy Sharpe is a former Clerk in the House of Commons. Her period as Clerk of the Journals provided her with significant insight into the historical and contemporary context of parliamentary conventions and procedure. Message from the Author With thanks to Dr Andrew Blick, Sir David Beamish, Helen Irwin and Sir Malcolm Jack for their comments on drafts of this paper. The conclusions, and any errors or omissions, are, of course, the responsibility of the author. Parliamentary Conventions Executive Summary “General agreement or consent, as embodied in any accepted usage, standard, etc”1 “Rules of constitutional practice that are regarded as binding in operation, but not in law”2 “[B]inding rules of behaviour accepted by those at whom they are directed. A practice that is not invariable does not qualify.”3 A list of various conventions with a note on how, if at all, they, or the approaches to them, have lately been modified or changed: CONVENTION CURRENT POSITION Conventions relating to behaviour in the House of Commons Speaking in the House of Commons Members should address the House through the Chair Although both questioned and frequently breached, and refer to other Members in the third person, by the convention is generally accepted constituency or position. Except for opening speeches, maiden speeches and Accepted and generally observed where there is special reason for precision, Members should not read speeches, though they may refer to notes Attendance at debates Members -

Westminster Hall PDF File 0.05 MB

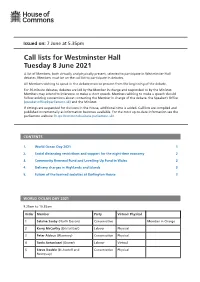

Issued on: 7 June at 5.35pm Call lists for Westminster Hall Tuesday 8 June 2021 A list of Members, both virtually and physically present, selected to participate in Westminster Hall debates. Members must be on the call list to participate in debates. All Members wishing to speak in the debate must be present from the beginning of the debate. For 30-minute debates, debates are led by the Member in charge and responded to by the Minister. Members may attend to intervene or make a short speech. Members wishing to make a speech should follow existing conventions about contacting the Member in charge of the debate, the Speaker’s Office ([email protected]) and the Minister. If sittings are suspended for divisions in the House, additional time is added. Call lists are compiled and published incrementally as information becomes available. For the most up-to-date information see the parliament website: https://commonsbusiness.parliament.uk/ CONTENTS 1. World Ocean Day 2021 1 2. Social distancing restrictions and support for the night-time economy 2 3. Community Renewal Fund and Levelling Up Fund in Wales 2 4. Delivery charges in Highlands and Islands 3 5. Future of the learned societies at Burlington House 3 WORLD OCEAN DAY 2021 9.25am to 10.55am Order Member Party Virtual/ Physical 1 Selaine Saxby (North Devon) Conservative Member in Charge 2 Kerry McCarthy (Bristol East) Labour Physical 3 Peter Aldous (Waveney) Conservative Physical 4 Tonia Antoniazzi (Gower) Labour Virtual 5 Steve Double (St Austell and Conservative Physical Newquay) -

Catholic Social Teaching: Sharing the Secret…

Catholic Social Teaching: Sharing the Secret… 1 September 2021 Volume 2, Number 9 In This Issue • Upcoming Events Tory MP Says ‘Some People Don't Need an Extra • Tory MP Says ‘Some People Don’t £20' Need An Extra £20’ No, he’s not talking about millionaires and billionaires, or even people who are in comfortable circumstances---Tory backbencher Andrew Rosindell has • Week of Action Sponsored by Stop argued that the extra £20 in Universal Credit brought in during the the Arms Fair coronavirus pandemic should be scrapped, saying “I think there are people • Forgiving Reality and Forgiving that quite like getting the extra £20 but maybe they don't need it.” Ourselves In contrast, Labour’s Carolyn Harris hit back, saying the £20 would be taken • Love, Justice and the Common Good away from “people who can least afford to lose it”. She added: “£20 is food • The Poor Evangelise Us for a week. £20 is a lifeline for people on Universal Credit.” Other Conservative party members also urged Chancellor Rishi Sunak to make the increase permanent. Former Tory leader and instigator of UPCOMING EVENTS Universal Credit Sir Iain Duncan Smith, along with five of his successors – Stephen Crabb, Damian Green, David Gauke, Esther McVey and Amber 1 September: World Day of Prayer for Rudd – have written to Sunak in an effort to persuade him to stick with the Season of Creation £5 billion benefits investment. 2-8 September: Week of Action to Sir Ian warned that a failure to keep the £20 uplift in place permanently protest the DSEI Arms Fair (see would “damage living standards, health and opportunities” for those that accompanying article in this issue). -

EU Referendum 2016 V7

EU Referendum 2016 Three Scenarios for the Government An insights and analysis briefing from The Whitehouse Consultancy Issues-led communications 020 7463 0690 [email protected] whitehouseconsulting.co.uk The EU Referendum The EU referendum has generated an unparalleled level of political If we vote to leave, a new Prime Minister will likely emerge from among debate in the UK, the result of which is still too close to call. Although the 'Leave' campaigners. What is questionable is whether Mr Cameron we cannot make any certain predictions, this document draws upon will stay in position to deal with the immediate questions posed by Whitehouse’s political expertise and media analysis to suggest what Brexit: such as the timetable for withdrawal, or how trading and may happen to the Government’s composition in the event of: diplomatic relations will proceed. Will he remain at Number 10, perhaps • A strong vote to remain (by 8% or more); until a party conference in the autumn, or will there be more than one new beginning? • A weak vote in favour of remaining (by up to 8%); or • A vote to leave. “The result could create If the UK chooses to remain by a wide margin, the subsequent reshue will aord an opportunity to repair the Conservative Party after a a new political reality.” bruising campaign period. This result will prompt a flurry of It is clear that the referendum result could create a new political reality on parliamentary activity, renewing the Prime Minister’s mandate until he 24 June. Businesses must be prepared to engage if they are to mitigate the stands down closer to 2020 and enable a continuation of the impacts and take advantage of the opportunities presented. -

Ministers' Gifts

Wales Office – Quarterly Ministerial Transparency Return MINISTERS’ GIFTS (GIVEN AND RECEIVED) GIFTS GIVEN OVER £140 Rt. Hon David Jones MP, Secretary of State for Wales Date gift given To Gift Value (over £140) Stephen Crabb MP, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Wales Date gift given To Gift Value (over £140) Baroness Randerson, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Wales Date gift given To Gift Value (over £140) Nil Return GIFTS RECEIVED OVER £140 Rt. Hon David Jones MP, Secretary of State for Wales Date gift From Gift Value Outcome received Retained by the Department/ Purchased by the Minister/ Used for official entertainment Stephen Crabb MP, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Wales Date gift From Gift Value Outcome received Retained by the Department/ Purchased by the Minister/ Used for official entertainment Wales Office – Quarterly Ministerial Transparency Return Baroness Randerson, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Wales Date gift From Gift Value Outcome received Nil return Retained by the Department/ Purchased by the Minister/ Used for official entertainment Wales Office – Quarterly Ministerial Transparency Return MINISTERS’ HOSPITALITY HOSPITALITY RECEIVED Rt. Hon David Jones MP, Secretary of State for Wales Date of Name of organisation - Type of hospitality received hospitality 4 October Fast Growth 50 Dinner 10 October EADS Lunch & Canapes 11 October European Space Agency Lunch Stephen Crabb MP, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Wales Date of Name of organisation - Type of hospitality