Between Prison and the Grave Enforced Disappearances in Syria Between Prison and the Grave Enforced Disappearances in Syria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syria: 'Nowhere Is Safe for Us': Unlawful Attacks and Mass

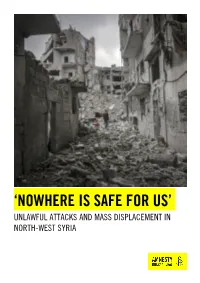

‘NOWHERE IS SAFE FOR US’ UNLAWFUL ATTACKS AND MASS DISPLACEMENT IN NORTH-WEST SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Ariha in southern Idlib, which was turned into a ghost town after civilians fled to northern (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. Idlib, close to the Turkish border, due to attacks by Syrian government and allied forces. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode © Muhammed Said/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 24/2089/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF NORTH-WEST SYRIA 4 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 2. METHODOLOGY 8 3. BACKGROUND 10 4. ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES AND SCHOOLS 12 4.1 ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES 14 AL-SHAMI HOSPITAL IN ARIHA 14 AL-FERDOUS HOSPITAL AND AL-KINANA HOSPITAL IN DARET IZZA 16 MEDICAL FACILITIES IN SARMIN AND TAFTANAZ 17 ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES IN 2019 17 4.2 ATTACKS ON SCHOOLS 18 AL-BARAEM SCHOOL IN IDLIB CITY 19 MOUNIB KAMISHE SCHOOL IN MAARET MISREEN 20 OTHER ATTACKS ON SCHOOLS IN 2020 21 5. -

Deir Ez-Zor: Dozens Arbitrarily Arrested During SDF's “Deterrence

Deir ez-Zor: Dozens Arbitrarily Arrested during SDF’s “Deterrence of Terrorism” Campaign www.stj-sy.org Deir ez-Zor: Dozens Arbitrarily Arrested during SDF’s “Deterrence of Terrorism” Campaign This joint report is brought by Justice For Life (JFL) and Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) Page | 2 Deir ez-Zor: Dozens Arbitrarily Arrested during SDF’s “Deterrence of Terrorism” Campaign www.stj-sy.org 1. Executive Summary The Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) embarked on numerous raids and arrested dozens of people in its control areas in Deir ez-Zor province, located east of the Euphrates River, during the “Deterrence of Terrorism” campaign it first launched on 4 June 2020 against the cells of the Islamic State (IS), aka Daesh. The reported raids and arrests were spearheaded by the security services of the Autonomous Administration and the SDF, particularly by the Anti-Terror Forces, known as the HAT.1 Some of these raids were covered by helicopters of the US-led coalition, eyewitnesses claimed. In the wake of the campaign’s first stage, the SDF announced that it arrested and detained 110 persons on the charge of belonging to IS, in a statement made on 10 June 2020,2 adding that it also swept large-scale areas in the suburbs of Deir ez-Zor and al-Hasakah provinces. It also arrested and detained other 31 persons during the campaign’s second stage, according to the corresponding statement made on 21 July 2020 that reported the outcomes of the 4- day operation in rural Deir ez-Zor.3 “At the end of the [campaign’s] second stage, the participant forces managed to achieve the planned goals,” the SDF said, pointing out that it arrested 31 terrorists and suspects, one of whom it described as a high-ranking IS commander. -

Was the Syria Chemical Weapons Probe “

Was the Syria Chemical Weapons Probe “Torpedoed” by the West? By Adam Larson Region: Middle East & North Africa Global Research, May 02, 2013 Theme: US NATO War Agenda In-depth Report: SYRIA Since the perplexing conflict in Syria first broke out two years ago, the Western powers’ assistance to the anti-government side has been consistent, but relatively indirect. The Americans and Europeans lay the mental, legal, diplomatic, and financial groundwork for regime change in Syria. Meanwhile, Arab/Muslim allies in Turkey and the Persian Gulf are left with the heavy lifting of directly supporting Syrian rebels, and getting weapons and supplementary fighters in place. The involvement of the United States in particular has been extremely lackluster, at least in comparison to its aggressive stance on a similar crisis in Libya not long ago. Hopes of securing major American and allied force, preferrably a Libya-style “no-fly zone,” always leaned most on U.S. president Obama’s announcement of December 3, 2012, that any use of chemical weapons (CW) by the Assad regime – or perhaps their simple transfer – will cross a “red line.” And that, he implied, would trigger direct U.S. intervention. This was followed by vague allegations by the Syrian opposition – on December 6, 8, and 23 – of government CW attacks. [1] Nothing changed, and the allegations stopped for a while. However, as the war entered its third year in mid-March, 2013, a slew of new allegations came flying in. This started with a March 19 attack on Khan Al-Assal, a contested western district of Aleppo, killing a reported 25-31 people. -

S/2019/321 Security Council

United Nations S/2019/321 Security Council Distr.: General 16 April 2019 Original: English Implementation of Security Council resolutions 2139 (2014), 2165 (2014), 2191 (2014), 2258 (2015), 2332 (2016), 2393 (2017), 2401 (2018) and 2449 (2018) Report of the Secretary-General I. Introduction 1. The present report is the sixtieth submitted pursuant to paragraph 17 of Security Council resolution 2139 (2014), paragraph 10 of resolution 2165 (2014), paragraph 5 of resolution 2191 (2014), paragraph 5 of resolution 2258 (2015), paragraph 5 of resolution 2332 (2016), paragraph 6 of resolution 2393 (2017),paragraph 12 of resolution 2401 (2018) and paragraph 6 of resolution 2449 (2018), in the last of which the Council requested the Secretary-General to provide a report at least every 60 days, on the implementation of the resolutions by all parties to the conflict in the Syrian Arab Republic. 2. The information contained herein is based on data available to agencies of the United Nations system and obtained from the Government of the Syrian Arab Republic and other relevant sources. Data from agencies of the United Nations system on their humanitarian deliveries have been reported for February and March 2019. II. Major developments Box 1 Key points: February and March 2019 1. Large numbers of civilians were reportedly killed and injured in Baghuz and surrounding areas in south-eastern Dayr al-Zawr Governorate as a result of air strikes and intense fighting between the Syrian Democratic Forces and Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant. From 4 December 2018 through the end of March 2019, more than 63,500 people were displaced out of the area to the Hawl camp in Hasakah Governorate. -

The Annual Report of the Most Notable Human Rights Violations in Syria in 2019

The Annual Report of the Most Notable Human Rights Violations in Syria in 2019 A Destroyed State and Displaced People Thursday, January 23, 2020 1 snhr [email protected] www.sn4hr.org R200104 The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), founded in June 2011, is a non-governmental, independent group that is considered a primary source for the OHCHR on all death toll-related analyses in Syria. Contents I. Introduction II. Executive Summary III. Comparison between the Most Notable Patterns of Human Rights Violations in 2018 and 2019 IV. Major Events in 2019 V. Most Prominent Political and Military Events in 2019 VI. Road to Accountability; Failure to Hold the Syrian Regime Accountable Encouraged Countries in the World to Normalize Relationship with It VII. Shifts in Areas of Control in 2019 VIII. Report Details IX. Recommendations X. References I. Introduction The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), founded in June 2011, is a non-govern- mental, non-profit independent organization that primarily aims to document all violations in Syria, and periodically issues studies, research documents, and reports to expose the perpetrators of these violations as a first step to holding them accountable and protecting the rights of the victims. It should be noted that Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights has relied, in all of its statistics, on the analysis of victims of the conflict in Syria, on the Syrian Network for Human Rights as a primary source, SNHR also collaborate with the Independent Inter- national Commission of Inquiry and have signed an agreement for sharing data with the Independent International and Impartial Mechanism, UNICEF, and other UN bodies, as well as international organizations such as the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. -

UNHCR's Operational Update: January-March 2019, English

OPERATIONAL UPDATE Syria January -March 2019 As of end of March, UNHCR In February, UNHCR participated in Since December a major emergency concluded its winterization the largest ever humanitarian in North East Syria led to thousands of programme with the distribution convoy providing life-saving people fleeing Hajin to Al-Hol camp. of 1,553,188 winterized humanitarian assistance to some UNHCR is providing core relief items to 1,163,494 individuals/ 40,000 displaced people at the items, shelter and protection 241,870 families in 13 governorates in Rukban ‘makeshift’ settlement in support for the current population Syria. south-eastern Syria, on the border which exceeds 73,000 individuals. with Jordan. HUMANITARIAN SNAPSHOT 11.7 million FUNDING (AS OF 16 APRIL 2019) people in need of humanitarian assistance USD 624.4 million requested for the Syria Operation 13.2 million Funded 14% people in need of protection interventions 87.4 million 11.3 million people in need of health assistance 4.7 million people in need of shelter Unfunded 86% 4.4 million 537 million people in need of core relief items POPULATION OF CONCERN Internally Displaced Persons Internally displaced persons 6.2 million Returnees Syrian displaced returnees 2018 1.4 million* Syrian refugee returnees 2018 56,047** Syrian refugee returnees 2019 21,575*** Refugees and Asylum seekers Current population 32,289**** Total urban refugees 17,832 Total asylum seekers 14,457 Camp population 30,529***** High Commissioner meets with families in Souran in Rural * OCHA, December 2018 Hama that have returned to their homes and received shelter ** UNHCR, December 2018 *** UNHCR, March 2019 assistance from UNHCR. -

Forgotten Lives Life Under Regime Rule in Former Opposition-Held East Ghouta

FORGOTTEN LIVES LIFE UNDER REGIME RULE IN FORMER OPPOSITION-HELD EAST GHOUTA A COLLABORATION BETWEEN THE MIDDLE EAST INSTITUTE AND ETANA SYRIA MAY 2019 POLICY PAPER 2019-10 CONTENTS * SUMMARY * KEY POINTS AND STATISTICS * 1 INTRODUCTION * 2 MAIN AREAS OF CONTROL * 3 MAP OF EAST GHOUTA * 6 MOVEMENT OF CIVILIANS * 8 DETENTION CENTERS * 9 PROPERTY AND REAL ESTATE UPHEAVAL * 11 CONCLUSION Cover Photo: Syrian boy cycles down a destroyed street in Douma on the outskirts of Damascus on April 16, 2018. (LOUAI BESHARA/AFP/Getty Images) © The Middle East Institute Photo 2: Pro-government soldiers stand outside the Wafideen checkpoint on the outskirts of Damascus on April 3, 2018. (Photo by LOUAI BESHARA/ The Middle East Institute AFP) 1319 18th Street NW Washington, D.C. 20036 SUMMARY A “black hole” of information due to widespread fear among residents, East Ghouta is a dark example of the reimposition of the Assad regime’s authoritarian rule over a community once controlled by the opposition. A vast network of checkpoints manned by intelligence forces carry out regular arrests and forced conscriptions for military service. Russian-established “shelters” house thousands and act as detention camps, where the intelligence services can easily question and investigate people, holding them for periods of 15 days to months while performing interrogations using torture. The presence of Iranian-backed militias around East Ghouta, to the east of Damascus, underscores the extent of Iran’s entrenched strategic control over key military points around the capital. As collective punishment for years of opposition control, East Ghouta is subjected to the harshest conditions of any of the territories that were retaken by the regime in 2018, yet it now attracts little attention from the international community. -

Detailed Account of 2014

Detailed Account of 2014 Syrian Network For Human Rights ۱ This report includes: First: Methodology ........................................................................ 1 Second: Active Parties ................................................................... 2 A. The Syrian government ............................................................ 2 B. Kurdish forces ................................................................. 18 C. Extremist factions .......................................................... 19 D. Armed opposition ......................................................... 22 E. Unidentified groups ....................................................... 23 Third: Recommendations ............................................................ 24 2 Syrian Network For Human Rights First The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) is an independ- Methodology ent nongovernmental nonprofit human rights organization that was founded in 2011 to document the ongoing violations in Syria and publish periodic studies,researches, and reports while maintaining the highest levels of professionalism and objectivity as a first step towards exposing violations perpetrators, hold them accountable, and insure victims’ rights. It should be noted that the U.N. relied on SNHR’s documentation, as its most prominent source, in all of its statistical and analytical reports concerning the victims of the Syrian conflict. Furthermore, SNHR is approved as a certified source by a wide range of Arabic and international news agencies and many international -

Recovery of Survivors of Improvised Explosive Devices and Explosive Remnants of War in Northeast Syria

Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction Volume 22 Issue 2 The Journal of Conventional Weapons Article 4 Destruction Issue 22.2 August 2018 Shattered Lives and Bodies: Recovery of Survivors of Improvised Explosive Devices and Explosive Remnants of War in Northeast Syria Médecins Sans Frontières MSF Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/cisr-journal Part of the Other Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, and the Peace and Conflict Studies Commons Recommended Citation Frontières, Médecins Sans (2018) "Shattered Lives and Bodies: Recovery of Survivors of Improvised Explosive Devices and Explosive Remnants of War in Northeast Syria," Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction: Vol. 22 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/cisr-journal/vol22/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for International Stabilization and Recovery at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction by an authorized editor of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Frontières: Recovery of Survivors of IEDs and ERW in Northeast Syria Shattered Lives and Bodies: Recovery of Survivors of Improvised Explosive Devices and Explosive Remnants of War in Northeast Syria by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) n northeast Syria, fighting, airstrikes, and artillery shell- children were playing when one of them took an object from ing have led to the displacement of hundreds of thousands the ground and threw it. They did not know it was a mine. It Iof civilians from the cities of Deir ez-Zor and Raqqa, as exploded immediately. -

EUROPEAN SEMINAR for EXCHANGE of GOOD PRACTICES Seminar Proceedings

Progetto co-finanziato FONDO ASILO MIGRAZIONE E INTEGRAZIONE 2014 – 2020 Progettodall’Unione co-finanziato Europea FONDO ASILO MIGRAZIONE E INTEGRAZIONE 2014 – 2020 dall’Unione Europea Obiettivo Specifico “2. Integrazione / Migrazione legale” – Obiettivo Nazionale “ON 3 – Capacity building – lett m) – Scambio di buone pratiche – inclusione sociale ed economica SM” Obiettivo Specifico “2. Integrazione / Migrazione legale” – Obiettivo Nazionale “ON 3 – Capacity building – lett m) – Scambio di buone pratiche – inclusione sociale ed economica SM” OCTOBER 17th 2019 Macro Asilo - Sala Cinema Roma Words4link - Scritture migranti per l’integrazione EUROPEAN SEMINAR FOR EXCHANGE OF GOOD PRACTICES seminar ProCeedinGs Edit by Sandra Federici and Elisabetta Degli Esposti Merli Greetings from Mercedes Giovinazzo Introduction by Elisabetta Degli Esposti Merli and Sandra Federici Moderation by Roberta Sangiorgi Speeches by Hanan Kassab-Hassan, Walid Nabhan, Mia Lecomte, Candelaria Romero Transcriptions by Federica Izzo Un progetto realizzato da: In collaborazione con: Progetto co-finanziato FONDO ASILO MIGRAZIONE E INTEGRAZIONE 2014 – 2020 dall’Unione Europea Obiettivo Specifico “2. Integrazione / Migrazione legale” – Obiettivo Nazionale “ON 3 – Capacity building – lett m) – Scambio di buone pratiche – inclusione sociale ed economica SM” Greetings from Mercedes Giovinazzo The European seminar for the exchange of good practices, held in Rome on October 17, 2019, at the Macro Asilo, opens with the projection of the video An intimate landscape, curated by Marco Trulli, a selection of works by young artists on the Mediterranean landscape: Vajiko Chachkhiani, Liryk Dela Kruz, Sirine Fat- touh, Randa Maddah and Nuvola Ravera. Each of them, even metaphorically, through the video, expressed the history and fears that characterize the vision of the place where we live. -

Spotlight on Global Jihad (May 6-12, 2021)

( רמה כ ז מל ו תשר מה ו ד י ע י ן ( למ מ"ל ןיעידומ ש ל מ כרמ ז מה י עד מל ו ד י ע י ן ו רטל ו ר ט ןיעידומ ע ה ר ( רמה כ ז מל ו תשר מה ו ד י ע י ן ( למ מ"ל ןיעידומ ש ל מ כרמ ז מה י עד מל ו ד י ע י ן ו רטל ו ר ט ןיעידומ ע ה ר Spotlight on Global Jihad May 6-12, 2021 Main events of the past week The fourth week of Ramadan was also marked by a relatively high number of attacks, mainly in Iraq and Africa. Syria: An IED was activated against a Syrian army ATV in the desert region (Al-Badia). The vehicle was destroyed and the passengers were killed or wounded. ISIS’s activity against the Kurdish SDF forces continued in the Deir ez-Zor-Al-Mayadeen region and in the Al-Raqqah region, where there was an increase in activity this week. Southern Syria: ISIS continued its activity against the Syrian army. This week, a soldier was targeted by gunfire in Naba al- Fawar, west of Daraa. He was killed. Iraq: The week, ISIS concentrated its activity mainly in the Kirkuk Province, where its operatives carried out several attacks against camps of the Iraqi security forces. ISIS operatives also blew up two oil wells in the area of Bai Hassan, northwest of Kirkuk, as part of the its so-called economic war. Africa: There appears to have been a slight decrease in ISIS’s activity this week. -

Consumed by War the End of Aleppo and Northern Syria’S Political Order

STUDY Consumed by War The End of Aleppo and Northern Syria’s Political Order KHEDER KHADDOUR October 2017 n The fall of Eastern Aleppo into rebel hands left the western part of the city as the re- gime’s stronghold. A front line divided the city into two parts, deepening its pre-ex- isting socio-economic divide: the west, dominated by a class of businessmen; and the east, largely populated by unskilled workers from the countryside. The mutual mistrust between the city’s demographic components increased. The conflict be- tween the regime and the opposition intensified and reinforced the socio-economic gap, manifesting it geographically. n The destruction of Aleppo represents not only the destruction of a city, but also marks an end to the set of relations that had sustained and structured the city. The conflict has been reshaping the domestic power structures, dissolving the ties be- tween the regime in Damascus and the traditional class of Aleppine businessmen. These businessmen, who were the regime’s main partners, have left the city due to the unfolding war, and a new class of business figures with individual ties to regime security and business figures has emerged. n The conflict has reshaped the structure of northern Syria – of which Aleppo was the main economic, political, and administrative hub – and forged a new balance of power between Aleppo and the north, more generally, and the capital of Damascus. The new class of businessmen does not enjoy the autonomy and political weight in Damascus of the traditional business class; instead they are singular figures within the regime’s new power networks and, at present, the only actors through which to channel reconstruction efforts.