Downloaded 2021-10-01T21:12:45Z

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studies in Celtic Languages and Literatures: Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Cornish

e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies Volume 9 Book Reviews Article 7 1-29-2010 Celtic Presence: Studies in Celtic Languages and Literatures: Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Cornish. Piotr Stalmaszczyk. Łódź: Łódź University Press, Poland, 2005. Hardcover, 197 pages. ISBN:978-83-7171-849-6. Emily McEwan-Fujita University of Pittsburgh Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi Recommended Citation McEwan-Fujita, Emily (2010) "Celtic Presence: Studies in Celtic Languages and Literatures: Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Cornish. Piotr Stalmaszczyk. Łódź: Łódź University Press, Poland, 2005. Hardcover, 197 pages. ISBN:978-83-7171-849-6.," e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies: Vol. 9 , Article 7. Available at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi/vol9/iss1/7 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact open- [email protected]. Celtic Presence: Studies in Celtic Languages and Literatures: Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Cornish. Piotr Stalmaszczyk. Łódź: Łódź University Press, Poland, 2005. Hardcover, 197 pages. ISBN: 978-83- 7171-849-6. $36.00. Emily McEwan-Fujita, University of Pittsburgh This book's central theme, as the author notes in the preface, is "dimensions of Celtic linguistic presence" as manifested in diverse sociolinguistic contexts. However, the concept of "linguistic presence" gives -

Gaelic Scotland – a Postcolonial Site? in Search of a Meaningful Theoretical Framework to Assess the Dynamics of Contemporary Scottish Gaelic Verse

eSharp Issue 6:1 Identity and Marginality Gaelic Scotland – A Postcolonial Site? In Search of a Meaningful Theoretical Framework to Assess the Dynamics of Contemporary Scottish Gaelic Verse Corinna Krause (University of Edinburgh) The late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries saw what is known today as the Highland Clearances, which was in effect the forced migration of a large proportion of the population of the Scottish Highlands due to intensified sheep farming in the name of a more effective economic land use (Devine, 1999, pp.176-78). For the Gaelic speech community this meant ‘the removal of its heartland’ (MacKinnon, 1974, p.47). MacKinnon argues that ‘effectively this was to reorientate the linguistic geography of Scotland in reducing the Gaelic areas to the very fringes of northern and western coastal areas and to the Hebrides’ (1974, p.47). Yet, it was not economic exploitation alone which influenced the existence of the Gaelic population in a most profound way. There was also an active interference with language use through the eradication of Gaelic from the sphere of education as manifested in a series of Education Acts from 1872 onwards. Such education policy ensured the integration of the Gaelic speech community into English-language Britain (MacKinnon, 1974, pp.54-74). Gaelic Scotland therefore had its share of experiencing what in postcolonial literary studies is identified as the ‘two indivisible foundations of imperial authority - knowledge and power’ (Ashcroft, Griffiths and Tiffin, 1995, p.1; referring to Said, -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

Etymology of the Principal Gaelic National Names

^^t^Jf/-^ '^^ OUTLINES GAELIC ETYMOLOGY BY THE LATE ALEXANDER MACBAIN, M.A., LL.D. ENEAS MACKAY, Stirwng f ETYMOLOGY OF THK PRINCIPAL GAELIC NATIONAL NAMES PERSONAL NAMES AND SURNAMES |'( I WHICH IS ADDED A DISQUISITION ON PTOLEMY'S GEOGRAPHY OF SCOTLAND B V THE LATE ALEXANDER MACBAIN, M.A., LL.D. ENEAS MACKAY, STIRLING 1911 PRINTKD AT THE " NORTHERN OHRONIOLB " OFFICE, INYBRNESS PREFACE The following Etymology of the Principal Gaelic ISTational Names, Personal Names, and Surnames was originally, and still is, part of the Gaelic EtymologicaJ Dictionary by the late Dr MacBain. The Disquisition on Ptolemy's Geography of Scotland first appeared in the Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness, and, later, as a pamphlet. The Publisher feels sure that the issue of these Treatises in their present foim will confer a boon on those who cannot have access to them as originally published. They contain a great deal of information on subjects which have for long years interested Gaelic students and the Gaelic public, although they have not always properly understood them. Indeed, hereto- fore they have been much obscured by fanciful fallacies, which Dr MacBain's study and exposition will go a long way to dispel. ETYMOLOGY OF THE PRINCIPAI, GAELIC NATIONAL NAMES PERSONAL NAMES AND SURNAMES ; NATIONAL NAMES Albion, Great Britain in the Greek writers, Gr. "AXfSiov, AX^iotv, Ptolemy's AXovlwv, Lat. Albion (Pliny), G. Alba, g. Albainn, * Scotland, Ir., E. Ir. Alba, Alban, W. Alban : Albion- (Stokes), " " white-land ; Lat. albus, white ; Gr. dA</)os, white leprosy, white (Hes.) ; 0. H. G. albiz, swan. -

The Origins and Expansion of the O'shea Clan

The Origins and Expansion of the O’Shea Clan At the beginning of the second millennium in the High Kingship of Brian Boru, there were three distinct races or petty kingdoms in what is now the County of Kerry. In the north along the Shannon estuary lived the most ancient of these known as the Ciarraige, reputed to be descendants of the Picts, who may have preceded the first Celts to settle in Ireland. On either side of Dingle Bay and inland eastwards lived the Corcu Duibne1 descended from possibly the first wave of Celtic immigration called the Fir Bolg and also referred to as Iverni or Erainn. The common explanation of Fir Bolg is ‘Bag Men’ so called as they allegedly exported Irish earth in bags to spread around Greek cities as protection against snakes! However as bolg in Irish means stomach, generations of Irish school children referred to them gleefully as ‘Fat bellies’ or worse. Legend has it that these Fir Bolg, as we will see possibly the ancestors of the O’Shea clan, landed in Cork. Reputedly small, dark and boorish they settled in Cork and Kerry and were the authors of the great Red Branch group of sagas and the builders of great stone fortresses around the seacoasts of Kerry. Finally around Killarney and south of it lived the Eoganacht Locha Lein, descendants of a later Celtic visitation called Goidels or Gaels. Present Kerry boundary (3) (2) (1) The territories of the people of the Corcu Duibne with subsequent sept strongholds; (1) O’Sheas (2) O’Falveys (3) O’Connells The Corcu Duibne were recognised as a distinct race by the fifth or sixth century AD. -

Taxi Kenmare

Page 01:Layout 1 14/10/13 4:53 PM Page 1 If it’s happening in Kenmare, it’s in the Kenmarenews FREE October 2013 www.kenmarenews.biz Vol 10, Issue 9 kenmareDon’t miss All newsBusy month Humpty happening for Dumpty at Internazionale Duathlon Kenmare FC ...See GAA ...See page page 40 ...See 33 page 32 SeanadóirSenator Marcus Mark O’Dalaigh Daly SherryAUCTIONEERS FitzGerald & VALUERS T: 064-6641213 Daly Coomathloukane, Caherdaniel Kenmare • 3 Bed Detached House • Set on c.3.95 acres votes to retain • Sea Views • In Need of Renovation •All Other Lots Sold atAuction Mob: 086 803 2612 the Seanad • 3.5 Miles to Caherdaniel Village Clinics held in the Michael Atlantic Bar and all € surrounding Offers In Excess of: 150,000 Healy-Rae parishes on a T.D. regular basis. Sean Daly & Co Ltd EVERY SUNDAY NIGHT IN KILGARVAN: Insurance Brokers HEALY-RAE’S MACE - 9PM – 10PM Before you Renew your Insurance (Household, Motor or Commercial) HEALY-RAE’S BAR - 10PM – 11PM Talk to us FIRST - 064-6641213 We Give Excellent Quotations. Tel: 064 66 32467 • Fax : 064 6685904 • Mobile: 087 2461678 Sean Daly & Co Ltd, 34 Henry St, Kenmare T: 064-6641213 E-mail: [email protected] • Johnny Healy-Rae MCC 087 2354793 Cllr. Patrick TAXI KENMARE Denis & Mags Griffin O’ Connor-ScarteenM: 087 2904325 Sneem & Kilgarvan 087 614 7222 Wastewater Systems See Notes on Page 16 Page 02:Layout 1 14/10/13 4:55 PM Page 1 2 | Kenmare News Mary Falvey was the winner of the baking Denis O'Neill competition at and his daughter Blackwater Sports, Rebecca at and she is pictured Edel O'Neill here with judges and Stephen Steve and Louise O'Brien's Austin. -

Barristers on Panel

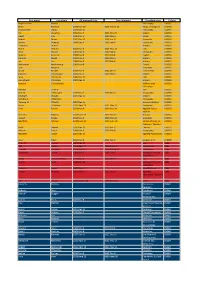

st Report Run Date: 21 Jun 2019 BARRISTERS ON PANEL The below list contains information on the number of payments* and the total amount paid to On Panel barristers for the period 1/07/18 – 31/12/18 Amount Number Amount Number Amount Number Amount Number Barrister Name Payable of Barrister Name Payable of Barrister Name Payable of Barrister Name Payable of (€) Payments (€) Payments (€) Payments (€) Payments Buckley, Declan 417,945 52 McGrath, Imogen 43,604 15 Binchy, Michael 11,132 8 Fitzpatrick, Andrew 3,094 6 Egan, Emily 394,952 24 Boughton, David 43,480 86 Farrelly, Aoife 10,908 13 Fitzgerald, William 2,653 11 Hanratty, Patrick 385,932 11 Fleck, Kieran 43,142 7 Delaney, Michael Patrick 10,701 2 MacMahon, Noel A. 2,583 1 Halpin, Conor 337,833 26 Gayer, Sasha Louise 39,452 4 Lydon, Eileen 10,578 2 Roberts, Conor 2,030 3 O'Braonain, Luan 231,215 17 Ramsey, Michael 37,023 1 Hand, Derry 10,376 8 Cheatle, John 1,845 1 Kavanagh, James M. 187,198 6 Fahey, Grainne 36,678 73 Scully, Lorraine 9,696 6 Maher, Jeremy 1,538 2 Foley, Brian 181,914 20 McGuinness, Donal 29,223 5 Hogan, John 9,545 7 Keleher, Daniel 1,162 1 Woulfe, Donnchadh 179,160 9 Lowe, Robert 28,226 2 Walsh, Aidan 8,979 1 Hewson, Dermot G. 1,119 1 McCrann, Oonah 159,623 18 Barrington, Eileen 27,596 2 Kilfeather, Jonathan 8,642 4 Keane, Deirdre 1,076 4 McCullough, Eoin 143,268 14 White, Rory 27,032 14 Fleming, David 8,107 2 Danaher, Gerard 954 2 Corcoran, Sarah 139,707 104 Farren, Georgina 25,227 5 Tennyson, Lauren 7,679 3 Cullinane, Padraig J. -

First Name Last Name GB Approval Date Date Informed Discipline/Area

First Name Last Name GB Approval Date Date Informed Discipline/area College Roger Garrett Barden Philosophy CACSSS Brian Bocking 2015 Nov 15 2016 March 14 Study of Religions CACSSS Desmond M Clarke 2007 Dec 11 Philosophy CACSSS Pat Coughlan 2013 Nov 5 2013 Nov 15 English CACSSS David Cox 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 Music CACSSS Robert Devoy 2011 Dec 13 2012 Jan 11 Geograhy CACSSS Francis Douglas 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 Education CACSSS Thomas J Dunne History CACSSS Maire Herbert 2013 Nov 5 2013 Nov 15 Irish CACSSS Aine Hyland 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 Education CACSSS Colbert Kearney 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 English CACSSS Dermot Keogh 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 History CACSSS Joe Lee 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 History CACSSS Mathew M MacNamara 2005 Nov 8 French CACSSS John Maguire Sociology CACSSS Grace Neville 2012 Nov 6 2012 Dec 6 French/T&L CACSSS Eamonn O Carragain 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 English CACSSS Sean O Coileain 2006 Dec 12 Irish CACSSS Donnchadh O Corrain 2007 Dec 11 History CACSSS Gearóid Ó Crualaoich Folklore and CACSSS Ethnology Padraig O Riain irish CACSSS Patrick O'Flanagan 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 Geography CACSSS Elisabeth Okasha 2007 Dec 11 English CACSSS Brendan E O'Mahony Philosophy CACSSS Terence W O'Reilly 2007 Dec 11 Hispanic Studies CACSSS Denis O'Sullivan 2011 April 19 2011 May 11 Education CACSSS Fred Powell 2014 Nov 4 2014 Nov 24 Applied Social CACSSS Studies Geoffrey Roberts 2017 June 13 2017 Dec 01 History CACSSS Joseph Ruane 2014 Nov 4 2014 Nov 24 Sociology CACSSS Manfred Schewe 2019 June 11 2019 June 18 School of Lang, Lit, CACSSS -

ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context

Mar Gur Dream Sí Iad Atá Ag Mairiúint Fén Bhfarraige: ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Darwin, Gregory R. 2019. Mar Gur Dream Sí Iad Atá Ag Mairiúint Fén Bhfarraige: ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42029623 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Mar gur dream Sí iad atá ag mairiúint fén bhfarraige: ML 4080 The Seal Woman in its Irish and International Context A dissertation presented by Gregory Dar!in to The Department of Celti# Literatures and Languages in partial fulfillment of the re%$irements for the degree of octor of Philosophy in the subje#t of Celti# Languages and Literatures (arvard University Cambridge+ Massa#husetts April 2019 / 2019 Gregory Darwin All rights reserved iii issertation Advisor: Professor Joseph Falaky Nagy Gregory Dar!in Mar gur dream Sí iad atá ag mairiúint fén bhfarraige: ML 4080 The Seal Woman in its Irish and International Context4 Abstract This dissertation is a study of the migratory supernatural legend ML 4080 “The Mermaid Legend” The story is first attested at the end of the eighteenth century+ and hundreds of versions of the legend have been colle#ted throughout the nineteenth and t!entieth centuries in Ireland, S#otland, the Isle of Man, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Norway, S!eden, and Denmark. -

A History of the O'shea Clan (July 2012)

A History of the O’Shea Clan (July 2012) At the beginning of the second millennium in the High Kingship of Brian Boru, there were three distinct races or petty kingdoms in what is now the County of Kerry. In the north along the Shannon estuary lived the most ancient of these known as the Ciarraige, reputed to be descendants of the Picts, who may have preceded the first Celts to settle in Ireland. On either side of Dingle Bay and inland eastwards lived the Corcu Duibne1 descended from possibly the first wave of Celtic immigration called the Fir Bolg and also referred to as Iverni or Erainn. Legend has it that these Fir Bolg, as we will see possibly the ancestors of the O’Shea clan, landed in Cork. Reputedly small, dark and boorish they settled in Cork and Kerry and were the authors of the great Red Branch group of sagas and the builders of great stone fortresses around the seacoasts of Kerry. Finally around Killarney and south of it lived the Eoganacht Locha Lein, descendants of a later Celtic visitation called Goidels or Gaels. Present Kerry boundary (3) (2) (1) The territories of the people of the Corcu Duibne with subsequent sept strongholds; (1) O’Sheas (2) O’Falveys (3) O’Connells The Eoganacht Locha Lein were associated with the powerful Eoganacht race, originally based around Cashel in Tipperary. By both military prowess and political skill they had become dominant for a long period in the South of Ireland, exacting tributes from lesser kingdoms such as the Corcu Duibne. -

From Munster to La Coruña Across the Celtic Sea: Emigration, Assimilation, and Acculturation in the Kingdom of Galicia (1601-40)

Obradoiro de Historia Moderna, N.º 19, 9-38, 2010, ISSN: 1133-0481 FROM MUNSTER TO LA CORUÑA ACROSS THE CELTIC SEA: EMIGRATION, ASSIMILATION, AND AccULTURATION IN THE KINGDOM OF GALICIA (1601-40) Ciaran O’Scea University College Dublin RESUMEN . Entre 1602 y 1608 cerca de 10.000 individuos de todos los estratos de la sociedad gaélica irlandesa predominante en el suroeste de Irlanda emigraron al noroeste de España como consecuenciade la fallida intervención militar española en Kinsale en 1601-02, lo que condujo a la consolidación de la comunidad irlandesa en La Coruña (Galicia). Esto ha permitido un análisis de la asimilación e integración de la comunidad en las estructuras civiles, eclesiásticas y reales de Galicia y de la monarquía hispánica. Los resultados muestran como la inicial introspección de la comunidad irlandesa durante la primera década dio paso a una rápida asimilación e integración en la siguiente. Al mismo tiempo, las alteradas circunstancias socio-económicas y políticas condujeron a cambios de gran alcance en las estructuras internas y los valores socio-culturales de la comunidad. Palabras clave: emigración irlandesa, España, Irlanda, Galicia, La Coruña, asimilación, integración, Kinsale. ABSTR A CT . Between 1602 and 1608 c. 10.000 individuals from all strata of predominantly Gaelic Irish society in the south west of Ireland emigrated to the north west of Spain in the aftermath of the failed Spanish military intervention at Kinsale in 1601-02, leading to the consolidation of the fledling Irish community in La Coruña in Galicia. This has permitted an analysis of the community´s assimilation and integration to the civil, ecclesiastical and royal structures of Galicia and the Spanish monarchy. -

Maccoinnich, A. (2008) Where and How Was Gaelic Written in Late Medieval and Early Modern Scotland? Orthographic Practices and Cultural Identities

MacCoinnich, A. (2008) Where and how was Gaelic written in late medieval and early modern Scotland? Orthographic practices and cultural identities. Scottish Gaelic Studies, XXIV . pp. 309-356. ISSN 0080-8024 http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/4940/ Deposited on: 13 February 2009 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk WHERE AND HOW WAS GAELIC WRITTEN IN LATE MEDIEVAL AND EARLY MODERN SCOTLAND? ORTHOGRAPHIC PRACTICES AND CULTURAL IDENTITIES This article owes its origins less to the paper by Kathleen Hughes (1980) suggested by this title, than to the interpretation put forward by Professor Derick Thomson (1968: 68; 1994: 100) that the Scots- based orthography used by the scribe of the Book of the Dean of Lismore (c.1514–42) to write his Gaelic was anomalous or an aberration − a view challenged by Professor Donald Meek in his articles ‘Gàidhlig is Gaylick anns na Meadhon Aoisean’ and ‘The Scoto-Gaelic scribes of late medieval Perth-shire’ (Meek 1989a; 1989b). The orthography and script used in the Book of the Dean has been described as ‘Middle Scots’ and ‘secretary’ hand, in sharp contrast to traditional Classical Gaelic spelling and corra-litir (Meek 1989b: 390). Scholarly debate surrounding the nature and extent of traditional Gaelic scribal activity and literacy in Scotland in the late medieval and early modern period (roughly 1400–1700) has flourished in the interim. It is hoped that this article will provide further impetus to the discussion of the nature of the literacy and literary culture of Gaelic Scots by drawing on the work of these scholars, adding to the debate concerning the nature, extent and status of the literacy and literary activity of Gaelic Scots in Scotland during the period c.1400–1700, by considering the patterns of where people were writing Gaelic in Scotland, with an eye to the usage of Scots orthography to write such Gaelic.