The Tongan Maritime Expansion: a Case in the Evolutionary Ecology Ofsocial Complexity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Zealand Aid and the Development of Class in Tonga : An

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. NEW ZEALAND AID AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CLASS IN TONGA: AN ANALYSIS OF THE BANANA REHABILITATION SCHEME A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY ANDREW P NEEDS DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY MASSEY UNIVERSITY FEBRUARY 1988 ii ABSTRACT This thesis examines the bilateral aid relationship between New Zealand and Tonga. Its central purpose is to examine the impact aid is having in transforming Tongan society. This involves a critique of both development theory and of New Zealand government aid principles. The understanding of development and the application of aid by the New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs remains greatly influenced by the modernisation school of thought, which essentially blames certain supposed attributes of Third World peoples for their lack of development. Dependency theorists challenged this view, claiming that Third World poverty was a direct result of First World exploitation through the unequal exchange of commodities. This has had some influence on the use of aid as a developmental tool, but has failed to supercede modernisation theory as the dominant ideology. The theory of articulation of modes of production transcends the problems of both modernisation and dependency schools. Its main thrust is that the capitalist (First World) mode of production does not immediately dominate the non-capitalist (Third World) mode but rather interacts with it. -

The Place of Alcohol in the Lives of People from Tokelau, Fiji, Niue

The place of alcohol in the lives of people from Tokelau, Fiji, Niue, Tonga, Cook Islands and Samoa living in New Zealand: an overview The place of alcohol in the lives of people from Tokelau, Fiji, Niue, Tonga, Cook Islands and Samoa living in New Zealand: an overview A report prepared by Sector Analysis, Ministry of Health for the Alcohol Advisory Council of New Zealand ALAC Research Monograph Series: No 2 Wellington 1997 ISSN 1174-1856 ISBN 0-477-06317-9 Acknowledgments This particular chapter which is an overview of the reports from each of the six Pacific communities would not have been possible without all the field teams and participants who took part in the project. I would like to thank Ezra Jennings-Pedro, Terrisa Taupe, Tufaina Taupe Sofaia Kamakorewa, Maikali (Mike) Kilioni, Fane Malani, Tina McNicholas, Mere Samusamuvodre, Litimai Rasiga, Tevita Rasiga, Apisa Tuiqere, Ruve Tuivoavoa, Doreen Arapai, Dahlia Naepi, Slaven Naepi, Vili Nosa, Yvette Guttenbeil, Sione Liava’a, Wailangilala Tufui , Susana Tu’inukuafe, Anne Allan-Moetaua, Helen Kapi, Terongo Tekii, Tunumafono Ken Ah Kuoi, Tali Beaton, Myra McFarland, Carmel Peteru, Damas Potoi and their communities who supported them. Many people who have not been named offered comment and shared stories with us through informal discussion. Our families and friends were drawn in and though they did not formally participate they too gave their opinions and helped to shape the information gathered. Special thanks to all the participants and Jean Mitaera, Granby Siakimotu, Kili Jefferson, Dr Ian Prior, Henry Tuia, Lita Foliaki and Tupuola Malifa who reviewed the reports and asked pertinent questions. -

University of Auckland Research Repository, Researchspace

Libraries and Learning Services University of Auckland Research Repository, ResearchSpace Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: • Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. • Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognize the author's right to be identified as the author of this thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. • You will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from their thesis. General copyright and disclaimer In addition to the above conditions, authors give their consent for the digital copy of their work to be used subject to the conditions specified on the Library Thesis Consent Form and Deposit Licence. Sauerkraut and Salt Water: The German-Tongan Diaspora Since 1932 Kasia Renae Cook A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in German, the University of Auckland, 2017. Abstract This is a study of individuals of German-Tongan descent living around the world. Taking as its starting point the period where Germans in Tonga (2014) left off, it examines the family histories, self-conceptions of identity, and connectedness to Germany of twenty-seven individuals living in New Zealand, the United States, Europe, and Tonga, who all have German- Tongan ancestry. -

Tokelau the Last Colony?

Tokelau The last colony? TONY ANGELO (Taupulega) is, and long has been, the governing body. The chairman (Faipule) of the council and a village head ITUATED WELL NORTH OF NEW ZEALAND and (Pulenuku) are elected by universal suffrage in the village SWestern Samoa and close to the equator, the small every three years. The three councils send representatives atolls of Tokelau, with their combined population of about to form the General Fono which is the Tokelau national 1600 people, may well be the last colony of New Zealand. authority; it originally met only once or twice a year and Whether, when and in what way that colonial status of advised the New Zealand Government of Tokelau's Tokelau will end, is a mat- wishes. ter of considerable specula- The General Fono fre- lion. quently repeated advice, r - Kirlb•ll ·::- (Gifb•rr I•) The recently passed lbn•b'a ' ......... both to the New Zealand (Oc: ..n I} Tokelau Amendment Act . :_.. PMtnb 11 Government and to the UN 1996- it received the royal Committee on Decoloni • •• roltfl•u assent on 10 June 1996, and 0/tlh.g• sation, that Tokelau did not 1- •, Aotum•- Uu.t (Sw•ln•J · came into force on 1 August 1 f .. • Tllloplol ~~~~~ !•J.. ·-~~~oa wish to change its status ~ ~ 1996 - is but one piece in ' \, vis-a-vis New Zealand. the colourful mosaic of •l . However, in an unexpected Tokelau's constitutional de change of position (stimu- velopment. lated no doubt by external The colonialism that factors such as the UN pro Tokelau has known has posal to complete its been the British version, and decolonisation business by it has lasted so far for little the year 2000), the Ulu of over a century. -

Sacred Kingship: Cases from Polynesia

Sacred Kingship: Cases from Polynesia Henri J. M. Claessen Leiden University ABSTRACT This article aims at a description and analysis of sacred kingship in Poly- nesia. To this aim two cases – or rather island cultures – are compared. The first one is the island of Tahiti, where several complex polities were found. The most important of which were Papara, Te Porionuu, and Tautira. Their type of rulership was identical, so they will be discussed as one. In these kingdoms a great role was played by the god Oro, whose image and the belonging feather girdles were competed fiercely. The oth- er case is found on the Tonga Islands, far to the west. Here the sacred Tui Tonga ruled, who was allegedly a son of the god Tangaloa and a woman from Tonga. Because of this descent he was highly sacred. In the course of time a new powerful line, the Tui Haa Takalaua developed, and the Tui Tonga lost his political power. In his turn the Takalaua family was over- ruled by the Tui Kanokupolu. The tensions between the three lines led to a fierce civil war, in which the Kanokupolu line was victorious. The king from this line was, however, not sacred, being a Christian. 1. INTRODUCTION Polynesia comprises the islands situated in the Pacific Ocean within the triangle formed by the Hawaiian Islands, Easter Island and New Zealand. The islanders share a common Polynesian culture. This cultural unity was established already in the eighteenth century, by James Cook, who ob- served during his visit of Easter Island in 1774: In Colour, Features, and Languages they [the Easter Islanders] bear such an affinity to the People of the more Western isles that no one will doubt that they have the same Origin (Cook 1969 [1775]: 279, 354–355). -

A History of the Pacific Islands

A HISTORY OF THE PACIFIC ISLANDS I. C. Campbell A HISTORY OF THE PACIFIC ISLANDS Thi s One l N8FG-03S-LXLD A History of the Pacific Islands I. C. CAMPBELL University of California Press Berkeley • Los Angeles Copyrighted material © 1989 I. C. Campbell Published in 1989 in the United States of America by the University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles All rights reserved. Apart from any fair use for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, no part whatsoever may by reproduced by any process without the express written permission of the author and the University of California Press. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Campbell, LC. (Ian C), 1947- A history of the Pacific Islands / LC. Campbell, p. cm. "First published in 1989 by the University of Canterbury Press, Christchurch, New Zealand" — T.p. verso. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-520-06900-5 (alk. paper). — ISBN 0-520-06901-3 (pbk. alk. paper) 1. Oceania — History. I. Title DU28.3.C35 1990 990 — dc20 89-5235 CIP Typographic design: The Caxton Press, Christchurch, New Zealand Cover design: Max Hailstone Cartographer: Tony Shatford Printed by: Kyodo-Shing Loong Singapore C opy righted m ateri al 1 CONTENTS List of Maps 6 List of Tables 6 A Note on Orthography and Pronunciation 7 Preface. 1 Chapter One: The Original Inhabitants 13 Chapter Two: Austronesian Colonization 28 Chapter Three: Polynesia: the Age of European Discovery 40 Chapter Four: Polynesia: Trade and Social Change 57 Chapter Five: Polynesia: Missionaries and Kingdoms -

THE HISTORY of the TONGA and FISHING COOPERATIVES in BINGA DISTRICT 1950S-2015

FACULTY OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY EMPOWERMENT OR CONTROL? : THE HISTORY OF THE TONGA AND FISHING COOPERATIVES IN BINGA DISTRICT 1950s-2015 BY HONOUR M.M. SINAMPANDE R131722P DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ARTS IN PARTIAL FULLFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE HONOURS DEGREE IN HISTORY AT MIDLANDS STATE UNIVERSITY. NOVEMBER 2016 ZVISHAVANE: ZIMBABWE SUPERVISOR DR. T.M. MASHINGAIDZE APPROVAL FORM The undersigned certify that they have supervised the student Honour M.M Sinampande (R131722P) dissertation entitled Empowerment or Control? : The history of the Tonga and fishing cooperatives in Binga District 1950-210 submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Bachelor of Arts in History Honours Degree offered by Midlands State University. Dr. T.M Mashingaidze ……………………… SUPERVISOR DATE …….……………………………………… …………………………….. CHAIRPERSON DATE ….………………………………………… …………………………….. EXTERNAL EXAMINER DATE DECLARATION I, Honour M.M Sinampande declare that, Empowerment or Control? : The history of the Tonga and fishing cooperatives in Binga District 1950s-2015 is my own work and it has never been submitted before any degree or examination in any other university. I declare that all sources which have been used have been acknowledged. I authorize the Midlands State University to lend this to other institution or individuals for purposes of academic research only. Honour M.M Sinampande …………………………………………… 2016 DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my father Mr. H.M Sinampande and my mother Ms. J. Muleya for their inspiration, love and financial support throughout my four year degree programme. ABSTRACT The history of the Tonga have it that, the introduction of the fishing villages initially and then later the cooperative system in Binga District from the 1950s-2015 saw the Zambezi Tonga lose their fishing rights. -

The Conflict Between Traditional Knowledge and Modernity in the Navigation of Polynesia

Journal of World Anthropology: Occasional Papers: Volume III, Number 2 48 “When earth and sky almost meet”: The Conflict between Traditional Knowledge and Modernity in Polynesian Navigation. Luke Strongman1 Abstract This paper provides an account of the differing ontologies of Polynesian and European navigation techniques in the Pacific. The subject of conflict between traditional knowledge and modernity is examined from nine points of view: The cultural problematics of textual representation, historical differences between European and Polynesian navigation; voyages of re-discovery and re-creation: Lewis and Finney; How the Polynesians navigated in the Pacific; a European history of Polynesian navigation accounts from early encounters; “Earth and Sky almost meet”: Polynesian literary views of recovered knowledge; lost knowledge in cultural exchanges – the parallax view; contemporary views and lost complexities. Introduction Polynesians descended from kinship groups in south-east Asia discovered new islands in the Pacific in the Holocene period, up to 5000 calendar years before the present day. The European voyages of discovery in the Pacific from the eighteenth century, in the Anthropocene era, brought Polynesian and European cultures together, resulting in exchanges that threw their cross-cultural differences into relief. As Bernard Smith suggests: “The scientific examination of the Pacific, by its very nature, depended on the level reached by the art of navigation” (Smith 1985:2). Two very different cultural systems, with different navigational practices, began to interact. 1 The Open Polytechnic of New Zealand Journal of World Anthropology: Occasional Papers: Volume III, Number 2 49 Their varied cultural ontologies were based on different views of society, science, religion, history, narrative, and beliefs about the world. -

Christianity and Taufa'āhau in Tonga

Melanesian Journal of Theology 23-1 (2007) CHRISTIANITY AND TAUFA‘ĀHAU IN TONGA: 1800-1850 Finau Pila ‘Ahio Revd Dr Finau Pila ‘Ahio serves as Principal of the Sia‘atoutai Theological College in Tonga. INTRODUCTION Near the centre of the Pacific Ocean lies the only island kingdom in the region, and the smallest in the world, Tonga. It is a group of small islands, numbering about 150, with only 36 of them inhabited, and which are scattered between 15º and 23º south latitude, and between 173º and 177º west longitude. The kingdom is divided into three main island groups: Tongatapu, situated to the south, Ha‘apai, an extensive archipelago of small islands in the centre, and Vava‘u, in the north. Tonga lies 1,100 miles northeast of New Zealand, and 420 miles southeast of Fiji. With a total area of 269 square miles, the population is more than 100,000, most of whom are native Polynesians. Tonga is an agricultural country, and most of the inhabited islands are fertile. The climate, however, is semi-tropical, with heavy rainfall and high humidity. Tonga, along with the rest of the Pacific, was completely unknown to Europe until the exploration of the area by the Spaniards and Portuguese during the 16th century. These explorers were seeking land to establish colonies, and to convert the inhabitants to Christianity. By the second decade of the 17th century, more explorers from other parts of Europe came into the area, to discover an unknown southern continent called “Terra Australis Incognita”, between South America and Africa. Among these, the Dutch were the first Europeans to discover Tonga. -

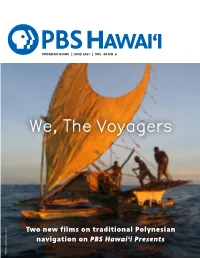

June Program Guide

PROGRAM GUIDE | JUNE 2021 | VOL. 40 NO. 6 Two new films on traditional Polynesian navigation on PBS Hawai‘i Presents Wade Fairley, copyright Vaka Taumako Project Taumako copyright Vaka Fairley, Wade A Long Story That Informed, Influenced STATEWIDE BOARD OF DIRECTORS and Inspired Chair The show’s eloquent description Joanne Lo Grimes nearly says it all… Vice Chair Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox Jason Haruki features engaging conversations with Secretary some of the most intriguing people in Joy Miura Koerte Hawai‘i and across the world. Guests Treasurer share personal stories, experiences Kent Tsukamoto and values that have helped shape who they are. Muriel Anderson What it does not express is the As we continue to tell stories of Susan Bendon magical presence Leslie brought to Hawai‘i’s rich history, our content Jodi Endo Chai will mirror and reflect our diverse James E. Duffy Jr. each conversation and the priceless communities, past, present and Matthew Emerson collection of diverse voices and Jason Fujimoto untold stories she captured over the future. We are in the process of AJ Halagao years. Former guest Hoala Greevy, redefining some of our current Ian Kitajima Founder and CEO of Paubox, Inc., programs like Nā Mele: Traditions in Noelani Kalipi may have said it best, “Leslie was Hawaiian Song and INSIGHTS ON PBS Kamani Kuala‘au HAWAI‘I, and soon we will announce Theresia McMurdo brilliant to bring all of these pieces Bettina Mehnert of Hawai‘i history together to live the name and concept of a new series. Ryan Kaipo Nobriga forever in one amazing library. -

Tsunami Recovery Priority Plan Niuatoputapu Kingdom of Tonga

12/23/13 Microsoft Word - Tsunami recovery priority plan Tonga NTT.doc Tsunami Recovery Priority Plan – Niuatoputapu Tonga 2009 Tsunami Recovery Priority Plan Niuatoputapu Kingdom of Tonga October 2009 1 www.pacificdisaster.net/pdnadmin/data/documents/3687.html 1/42 12/23/13 Microsoft Word - Tsunami recovery priority plan Tonga NTT.doc Tsunami Recovery Priority Plan – Niuatoputapu Tonga 2009 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY …………………………………………………….………. 3 SECTION 0: ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ……………………………………………. 4 SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION ………………………………………………………………………… 5 1.1 Background ……………………………………………………………………… 5 1.2 Scope and Content ………………………………………………………….. 7 1.3 Goal ………………………………………………………………………………… 8 1.4 Guiding principles ……………………………………………………………. 8 SECTION 2: COORDINATION ARRANGEMENTS ……………………………………………. 9 SECTION 3: DAMAGE ASSESSMENTS AND PRIORITIES FOR RECOVERY ……….. 11 3.1 Damage assessments ………………………………………………………. 11 3.2 Initial priorities ……………………………………………………………….. 11 3.3 Sectoral analysis …………………………………………………………….. 12 3.4 Logistics …………………………………………………………………………. 16 3.5 Recovery strategies and actions matrix …………………………... 18 SECTION 4: FUNDING ……………………………………………………………………………..…. 23 SECTION 5: RISK ANALYSIS ………………………………………………………………………… 23 SECTION 6: NEXT STEPS …………………………………………………………………………….. 23 SECTION 7: CONCLUSIONS ………………………………………………………………………… 22 ANNEX 1: Immediate and long term needs ……………………………..………………………. 25 ANNEX 2: Summary of indicative external assistance ……………………………………… 33 ANNEX 3: Table of estimated damages …………………………………………………………… -

The Tonga Chronicle, and Has Even Ate

m • POLITICAL REVIEWS 195 began to reactivate local government to democracy are disrespectful to the improve its image and communications monarch and nobles, and threaten with village people. The police minister Tonga's heritage. The prodemocracy continued to speak against the prode supporters are equally convinced that mocracy supporters in his weekly col steps forward can be made peacefully umn in the government-run newspaper by a gradual education ofthe elector the Tonga Chronicle, and has even ate. The increasing number of non threatened them with violence. After government controlled newssheets, the election he wrote "The continual papers, and magazines launched in sly hints ofcorruption and dishonesty Tonga play an important role in in against His Majesty's Government creasing people's awareness of signifi without proofis going to rebound with cant issues. Several popular leaders multiple traumatic consequences on have emerged. But the cabinet together those concerned" (Tonga Chronicle, II with the nobles' representatives still Feb 1993, 3)· controls the majority in Parliament, In addition, not all members ofthe and the king retains the power to create churches are behind their leaders' call ministers of state who will support the for political reform. People have asked oligarchy. It is difficult, therefore, to that church newspapers omit political see how democratic change might comment and concentrate only on the occur in the foreseeable future, except teachings ofthe gospel and church by royal fiat which would imply an news. An advisor is to be appointed to emphatic change ofroyal heart. The counsel Free Wesleyan Church mem present situation, which is one of stale bers regarding the denomination's offi mate, shows that the prodemocracy cial stands on political and social issues movement still has a lot ofeducating (Tonga Chronicle, 20 May 1993, 5).