AJQU No. 36

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2002-2003 the Lynn University Philharmonia Orchestra

THE CONSERVATORY OF MUSIC Presents "THE LYNN UNIVERSITY PHILHARMONIA ORCHESTRA'' DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF RUTH NELSON KRAFT Saturday, November 9, 2002 7:30 p.rn. The Green Center Introduction - Graciela Helguero, Assistant Professor, Spanish Overture in G ("Burlesque de Quichotte") ............. Georg Philip Telemann Overture Awakening on the Windmills Sighs of Love for Princess Aline Sancho Panza Swindled Don Quixote (Trombone Concerto #2) .................................. Jan Sandstrom Introduction - A Windmill Ride To Walk Where the Bold Man Makes a Halt To Row Against a Rushing Stream To Believe in an Insane Dream To Smile Despite Unbearable Pain And Yet When You Succumb,Try to Reach this Star in the Sky Mark Hetzler, trombone INTERMISSION Don Quixote............................................................................ Richard Strauss Introduction Don Quixote - Sancho Panza Var. I: Departure; the Adventure with the Windmills Var. II: The Battle with the Sheep Var. ill: Sancho's Wishes, Peculiarities of Speech and Maxims Var. IV: The Adventure with the Procession of Penitents Var. V: Don Quixote's Vigil During the Summer Night Var. VI: Dulcinea Var. VII: Don Quixote's Ride Through the Air Var. Vill: The Trip on the Enchanted Boat Var. IX: The Attack on the Mendicant Friars Var. X: The Duel and Return Home Epilogue: Don Quixote's Mind Clears. Death of Don Quixote Johanne Perron, cello rthur eisberg, conductor Mr. Weisberg is considered to be among the world's leading bassoonists. He has played with the Houston, Baltimore, and Cleveland Orchestras, as well as with the Symphony of the Air and the New York Woodwind Quintet. As a music director, Mr. Weisberg has worked with the New Chamber Orchestra of Westchester, Orchestra de Camera (of Long Island, New York), Contemporary Chamber Ensemble, Orchestra of the 20th Century, Stony Brook Symphony, Iceland Symphony, and Ensemble 21. -

Release Sheet

November 17, 2017 November 17, 2017 TALES OF TWO CITIES The Leipzig-Damascus Coffee House “powerful” “flawless” — The Globe and Mail — Musical Toronto Tafelmusik’s stunning multimedia concert Tales of Two Cities: The Leipzig-Damascus Coffee House is now available as a CD soundtrack and DVD that was filmed before a live audience at the Aga Khan Museum’s auditorium in Toronto. Inspired by the colourful, opulent world of 18th-century Saxon and Syrian coffee houses, Tales of Two Cities is performed entirely from memory by Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra, ensemble Trio Arabica — Maryem Tollar, voice and qanun; Demetri Petsalakis, oud; and Naghmeh Farahmand, percussion — with narrator Alon Nashman. Described as an “enterprising concept … [that] blends elements that are entertaining, educational, musically rewarding and visually arresting” (Huffington Post Canada), Tales of Two Cities received rapturous critical acclaim at its May 2016 Toronto premiere and was named Best Concert of 2016 by the Spanish classical music magazine Codalario.com. DVD extras include subtitles in Arabic, a video on the restoration of the Dresden Damascus Room, behind-the-scenes footage from rehearsals, and a nine-camera split screen video of the orchestra performing Bach’s Sinfonia after BWV 248 in a new arrangement by Tafelmusik. TALES OF TWO CITIES The Leipzig-Damascus Coffee House DVD (Total Duration 1:37:15) CHAPTERS LISTING Chapter 1: Opening credits/Overture 5:41 Chapter 2: Coffee travels from the Middle East to Venice and Paris 15:57 Chapter 3: Coffee comes to Leipzig -

'Dream Job: Next Exit?'

Understanding Bach, 9, 9–24 © Bach Network UK 2014 ‘Dream Job: Next Exit?’: A Comparative Examination of Selected Career Choices by J. S. Bach and J. F. Fasch BARBARA M. REUL Much has been written about J. S. Bach’s climb up the career ladder from church musician and Kapellmeister in Thuringia to securing the prestigious Thomaskantorat in Leipzig.1 Why was the latter position so attractive to Bach and ‘with him the highest-ranking German Kapellmeister of his generation (Telemann and Graupner)’? After all, had their application been successful ‘these directors of famous court orchestras [would have been required to] end their working relationships with professional musicians [take up employment] at a civic school for boys and [wear] “a dusty Cantor frock”’, as Michael Maul noted recently.2 There was another important German-born contemporary of J. S. Bach, who had made the town’s shortlist in July 1722—Johann Friedrich Fasch (1688–1758). Like Georg Philipp Telemann (1681–1767), civic music director of Hamburg, and Christoph Graupner (1683–1760), Kapellmeister at the court of Hessen-Darmstadt, Fasch eventually withdrew his application, in favour of continuing as the newly- appointed Kapellmeister of Anhalt-Zerbst. In contrast, Bach, who was based in nearby Anhalt-Köthen, had apparently shown no interest in this particular vacancy across the river Elbe. In this article I will assess the two composers’ positions at three points in their professional careers: in 1710, when Fasch left Leipzig and went in search of a career, while Bach settled down in Weimar; in 1722, when the position of Thomaskantor became vacant, and both Fasch and Bach were potential candidates to replace Johann Kuhnau; and in 1730, when they were forced to re-evaluate their respective long-term career choices. -

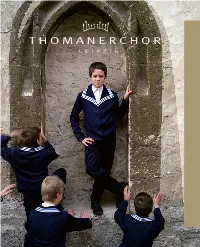

T H O M a N E R C H

Thomanerchor LeIPZIG DerThomaner chor Der Thomaner chor ts n te on C F o able T Ta b l e o f c o n T e n T s Greeting from “Thomaskantor” Biller (Cantor of the St Thomas Boys Choir) ......................... 04 The “Thomanerchor Leipzig” St Thomas Boys Choir Now Performing: The Thomanerchor Leipzig ............................................................................. 06 Musical Presence in Historical Places ........................................................................................ 07 The Thomaner: Choir and School, a Tradition of Unity for 800 Years .......................................... 08 The Alumnat – a World of Its Own .............................................................................................. 09 “Keyboard Polisher”, or Responsibility in Detail ........................................................................ 10 “Once a Thomaner, always a Thomaner” ................................................................................... 11 Soli Deo Gloria .......................................................................................................................... 12 Everyday Life in the Choir: Singing Is “Only” a Part ................................................................... 13 A Brief History of the St Thomas Boys Choir ............................................................................... 14 Leisure Time Always on the Move .................................................................................................................. 16 ... By the Way -

An Introduction to the Annotated Bach Scores - Sacred Cantatas Melvin Unger

An Introduction to the Annotated Bach Scores - Sacred Cantatas Melvin Unger Abbreviations NBA = Neue Bach Ausgabe (collected edition of Bach works) BC = Bach Compendium by Hans-Joachim Schulze and Christoph Wolff. 4 vols. (Frankfurt: Peters, 1989). Liturgical Occasion (Other Bach cantatas for that occasion listed in chronological order) *Gospel Reading of the Day (in the Lutheran liturgy, before the cantata; see below) *Epistle of the Day (in the Lutheran liturgy, earlier than the Gospel Reading; see below) FP = First Performance Note: Some of the following material is taken from Melvin Unger’s overview of Bach’s sacred cantatas, prepared for Cambridge University Press’s Bach Encyclopedia. Copyright Melvin Unger. That overview (which is available here with the annotated Bach cantata scores) includes a bibliography. Additional, online sources include the Bach cantatas website at https://www.bach-cantatas.com/ and Julian Mincham’s website at http://www.jsbachcantatas.com/. The German Cantata Before Bach In Germany, Lutheran composers adapted the genre that had originated in Italy as a secular work intended for aristocratic chamber settings. Defined loosely as a work for one or more voices with independent instrumental accompaniment, usually in discrete sections, and employing the ‘theatrical’ style of opera, the Italian cantata it was originally modest in scope—usually comprising no more than a couple of recitative-aria pairs, with an accompaniment of basso continuo. By the 1700s, however, it had begun to include other instruments, and had grown to include multiple, contrasting movements. Italian composers occasionally wrote sacred cantatas, though not for liturgical use. In Germany, however, Lutheran composers adapted the genre for use in the main weekly service, where it subsumed musical elements already present: the concerted motet and the chorale. -

'{6$+• O°&Ó° Þè* V

557615bk Bach US 3/5/06 6:10 pm Page 5 Marianne Beate Kielland Cologne Chamber Orchestra Conductor: Helmut Müller-Brühl The Norwegian mezzo-soprano Marianne Beate Kielland studied at the Norwegian State Academy of Music in Oslo, graduating in the spring of 2000. She has quickly The Cologne Chamber Orchestra was founded in 1923 by Hermann Abendroth and gave established herself as one of Scandinavia’s foremost singers and regularly appears its first concerts in the Rhine Chamber Music Festival under the direction of Hermann with orchestras and in festivals throughout Europe, working with conductors of Abendroth and Otto Klemperer in the concert-hall of Brühl Castle. Three years later the international distinction. For the season 2001/02 she was a member of the ensemble ensemble was taken over by Erich Kraack, a pupil of Abendroth, and moved to at the Staatsoper in Hanover. Marianne Beate Kielland is especially sought after as a Leverkusen. In 1964 he handed over the direction of the Cologne Chamber Orchestra to J. S. BACH concert singer, with a wide repertoire ranging from the baroque to Berlioz, Bruckner, Helmut Müller-Brühl, who, through the study of philosophy and Catholic theology, as and Mahler. Her career has brought not only performances in Europe, but further well as art and musicology, had acquired a comprehensive theoretical foundation for the engagements as far afield as Japan. Her recordings include Bach’s St Mark and St interpretation of Baroque and Classical music, complemented through the early study of Matthew Passions, Mass in B minor, and the complete solo cantatas for alto, as well conducting and of the violin under his mentor Wolfgang Schneiderhahn. -

Teilplan Flughafen Frankfurt/Main

Regierungspräsidium Darmstadt Lärmaktionsplan Hessen Teilplan Flughafen Frankfurt/Main Impressum Regierungspräsidium Darmstadt Luisenplatz 2 64283 Darmstadt Tel.: +49 (0)6151/12-0 Fax: +49 (0)6151/12-6313 www.rp-darmstadt.hessen.de Postanschrift: Regierungspräsidium Darmstadt 64278 Darmstadt Unter fachlicher Mitwirkung der ACCON GmbH www.accon.de Stand: 5. Mai 2014 Vorwort Der Flughafen Frankfurt/Main als Deutschlands größtes Luft- verkehrsdrehkreuz hat für die Mobilität und die wirtschaftliche Entwicklung weit über den Regierungsbezirk Darmstadt und Hessen hinaus eine große Bedeutung. Dies führt auf Seiten der betroffenen Wohnbevölkerung jedoch häufig auch zu erhebli- chen Lärmbelastungen. Der Frankfurter Flughafen stellt für die Region daher einerseits einen bedeutsamen wirtschaftlichen Standortfaktor dar, muss andererseits jedoch immer auch den Bedürfnissen der Anwohner auf Erhalt einer lebenswerten Um- welt Rechnung tragen. Der vorliegende Lärmaktionsplan für den Flughafen Frankfurt/Main nimmt eine Auswer- tung der gegenwärtigen und zukünftigen Lärmsituation vor und stellt in Verbindung mit den technischen und rechtlichen Rahmenbedingungen Minderungsmaßnahmen dar, die bereits eingeführt wurden oder darüber hinaus derzeit geplant oder geprüft werden. Im Rahmen der Öffentlichkeitsbeteiligung zur Aufstellung des Lärmaktionsplans gingen knapp 11.000 Stellungnahmen ein. Die hohe Beteiligung und die Vielzahl der vorgeschla- genen Lärmminderungsmaßnahmen verdeutlichen den besonderen Stellenwert, den das Thema Fluglärm bei der betroffenen -

GEORG PHILIPP TELEMANN Musikalische Werke (Auswahlausgabe)

Musikwissenschaftliche Editionen – Publikationsverzeichnis – Stand: Mai 2019 GEORG PHILIPP TELEMANN Musikalische Werke (Auswahlausgabe) (Finanzierung durch das Akademienprogramm bis 31.12.2010) Herausgeber: Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur, Mainz, in Verbindung mit dem Zentrum für Telemann-Pflege und -Forschung Magdeburg. Anschrift: Telemann-Auswahlausgabe, Schönebecker Str. 129, 39104 Magdeburg Verlag: Bärenreiter-Verlag, Kassel Umfang der Ausgabe: 50 Bände mit Kritischen Berichten und 3 Supplementbände. Band I: Zwölf methodische Sonaten. 1–6 für Violine oder Querflöte und Basso continuo, 7–12 für Querflöte oder Violine und Basso continuo. Hamburg 1728 und 1732. Herausgegeben von Max Seiffert. 1955, 71983. VIII, 126 S. Band II: Der Harmonische Gottesdienst. Ein Jahrgang von 72 Solokantaten für 1 Singstimme, 1 Instrument und Basso continuo. Hamburg 1725/1726. Teil I [Nr. 1–15]: Neujahr bis Reminiscere. Herausgegeben von Gustav Fock. 1953, ³1981. XI, 132 S. Band III: Der Harmonische Gottesdienst. Ein Jahrgang von 72 Solokantaten für 1 Singstimme, 1 Instrument und Basso continuo. Hamburg 1725/1726. Teil II [Nr. 16–31]: Oculi bis 1. Pfingsttag. Herausgegeben von Gustav Fock. 1953, ³1982. IV, 140 S. Band IV: Der Harmonische Gottesdienst. Ein Jahrgang von 72 Solokantaten für 1 Singstimme, 1 Instrument und Basso continuo. Hamburg 1725/1726. Teil III [Nr. 32–50]: 2. Pfingsttag bis 16. Sonntag nach Trinitatis. Herausgegeben von Gustav Fock. 1970, 41998. VII, 152 S. Band V: Der Harmonische Gottesdienst. Ein Jahrgang von 72 Solokantaten für 1 Singstimme, 1 Instrument und Basso continuo. Hamburg 1725/1726. Teil IV [Nr. 51–72]: 17. Sonntag nach Trinitatis bis Sonntag nach Weihnachten. Herausgegeben von Gustav Fock. 1957. VII, 163 S. Band VI: Kammermusik ohne Generalbaß [I]. -

‚Aufgeweckte Einfälle' Und ‚Sinnreiche Gedanken' – Witz Und Humor

‚aufgeweckte Einfälle‘ und ‚sinnreiche Gedanken‘ – Witz und Humor in Ouvertürensuiten Georg Philipp Telemanns Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Universität Heidelberg vorgelegt von: Sarah-Denise Fabian Erstgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Silke Leopold Zweitgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Dorothea Redepenning Heidelberg, Juli 2014, überarbeitete Fassung August 2015 Für meine Eltern und Großeltern Dank Bei der vorliegenden Arbeit handelt es sich um eine geringfügig überarbeitete Fassung meiner im Juli 2014 von der Philosophischen Fakultät der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg an- genommenen Dissertation. Während ihrer Entstehung habe ich diverse Unterstützungen ver- schiedener Personen und Einrichtungen erhalten. Zu allererst gebührt Prof. Dr. Silke Leopold für die Betreuung der Arbeit ein herzliches Dankeschön! Sie hat alle Phasen der Dissertation – Themenfindung, Anlage und Konzeption, Verschriftlichung – mit wertvollen Hinweisen und Anregungen zum Über- und Weiterdenken begleitet. Außerdem hat sie mir ermöglicht, wäh- rend der gesamten Promotionsphase ununterbrochen unter anderem als wissenschaftliche Hilfs- kraft am Musikwissenschaftlichen Seminar der Universität Heidelberg angestellt zu sein, und damit einen finanziellen Rahmen für die Arbeit geschaffen. Dafür bin ich ihr ebenfalls sehr dankbar. Daneben hat Prof. Dr. Dorothea Redepenning im Doktorandenkolloquium immer wie- der das Projekt mit nützlichen Ratschlägen unterstützt und zudem dankenswerterweise das Zweitgutachten übernommen. Überhaupt danke ich allen Teilnehmern des Doktorandenkollo- quiums: Zum einen habe ich in den Diskussionen nach meinen Referaten stets positive Anre- gungen für die Gestaltung der einzelnen Kapitel erhalten, zum anderen hat die Lektüre kultur- wissenschaftlich orientierter Texte im Rahmen des Kolloquiums dazu geführt, gewinnbringend aus einer anderen Blickrichtung auf die eigene Arbeit zu schauen. Den Vorsitz bei meiner im Dezember 2014 stattgefundenen Disputatio hat freundlicherweise PD Dr. -

Pimpinone & La Serva Padrona

© Marc Vanappelghem Pimpinone & La serva padrona opéra de chambre de G.P. Telemann & G.B. Pergolesi par l’Opéra de Lausanne mise en scène Eric Vigié di 9 janvier 17h grande salle Dossier de presse Théâtre du Passage Saison 2010-2011 Chargé de communication: Benoît Frachebourg | 032 717 82 05 | [email protected] DOSSIER DE PRESSE Contact Presse : Elisabeth Demidoff Tel : 079 679 43 90 Email : [email protected] 1 SOMMAIRE LA ROUTE LYRIQUE VAUD 2010 page 3 PIMPINONE page 4 Georg Philipp Telemann LA SERVA PADRONA Giovanni Battista Pergolesi DISTRIBUTION page 5 SYNOPSIS page 6 LA TOURNEE - dates et lieux page 7 BIOGRAPHIES page 9 LES MÉCÈNES DE LA ROUTE LYRIQUE page 15 INFORMATIONS PRATIQUES page 16 2 LA ROUTE LYRIQUE L'Opéra de Lausanne se lance pour la première fois de son histoire, avec l’aide et le soutien du Canton de Vaud (Service des affaires Culturelles) dans une tournée estivale unique en son genre. Nous partons à la rencontre du public, et vous proposons de nous suivre durant le mois de juillet dans les villes qui ont accepté de nous recevoir. Pimpinone (1725) et La serva padrona (1733) constituent deux des chefs-d’oeuvre de l’opéra buffa naissant. Si le premier a été créé à Hambourg, par LE compositeur allemand le plus important du début du XVIIIe siècle (Telemann) abordant un thème bien osé pour l’époque, le second est d’une veine toute napolitaine et donnera naissance à la comédie bouffe dans toute sa splendeur. Il est intéressant de vous les présenter ensemble, dans une atmosphère proche de ce que l’on attend -

2018-10-11 DADINA Landkreis Darmstadt-Dieburg

RE85 RB86 Dudenhofen K86 K66 Hanau Route map District of Darmstadt-Dieburg S1 Continental K86 Jürgen-Schumann-Straße Elsässer Straße to the airport Frankfurter Str. Babenhausen K86 Bürgermeister-Willand-Straße Frankfurt-Flughafen Frankfurt Neu-Isenburg Rödermark- Frankfurt Frankfurt K66 751 RE60 RB67/68 RB82 S3 662 U RB61 S1 4143 Luisenstraße Joachim-Schumann-Schule Mörfelden-Walldorf Langen Langen Urberach Dreieich-Buchschlag Offenbach Ludwigstr. Harreshausen Friedhof K66 Rödermark Ober-Roden Bf. S1 X74 674 679 Stadthalle K66 Aschaffenburg Babenhausen Bf. K66 Erzhausen Bf. Siedlung Breidert Bürgermeister-Rühl-Str. RB75 HessenplatzLangener Str K53 K54 K65 K66 K86 Sickenhofen . Lessingstraße Darmstädter Str Kirche Kaserne Aschaffenburger Str. Nord Eppertshausen Feldstr HessenwaldschuleAm Ohlenberg . 4138 Im Riemen Abzweig Erzhausen ME Mitte Schneppenhäuser Str Hergershausen K65,671 K53,K54,671 WE1 Ost . Worfelden WE2 Am Mörsbach Eppertshausen Bf. Schule Erzhausen Süd Jahnstraße Am Rotböll ME,X74 Aue RB75 PostplatzOstendstr 674,679 . Messel U Rathaus RE85,RB86 Schneppen- 4089 Hegershausen Bf. 4080 RB61 Auf der eg hausen ixhausen Bf. Wixhausen Sudetenstraße K53 . Sportplatz W Münster Feuerwehr WX Merianstraße/GSIG 4035 Industriering 671 FrankfurterSchule StrMD Harpertshausen K54,671 WE1 G Messeler Park Str. 4138 Schulstraße Gräfen- WE1 Gartenstr. Kulturhalle ME Linde Heimatring 1) Industriestraße BahnübergangBreuberger W Sporthalle hausen Am Ohlenbach Münster Bf. Langstadt Ärztehaus Messel Bahnhof 2) Dammweg Fr.-Ebert-Straße 671 K65 Langstadt GU1 K65 Aschaffenburg WE1 Zentrum Arheilgen Bf. 6 7 8 WX G 662 3) Dieselstraße ME RathausAueweg Braunshardt 751 SV Sportplatz Waldstraße Apotheke K53 Arheilgen Dreieichweg Grube Messel Am Wildpark Hallenbad Altheim Bf. Bahnhof K65 Sportplatz Liebigstr. Feuerwehrhaus Gasthaus SchützenhofSchaafheim Schloß Kolpingweg Arheilgen Grube Messel Besucherzentrum ME John-F.-Kennedy-Schule WE2 RB75 Nordring GA ME GU1,K65 4153 Dornheckeeiterstadt Bf. -

THE ARTS of PERSUASION (Revised)

The Arts of Persuasion: Musical Rhetoric in the Keyboard Genres of Dieterich Buxtehude Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Anderson, Ron James Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 20:06:37 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/242454 THE ARTS OF PERSUASION: MUSICAL RHETORIC IN THE KEYBOARD GENRES OF DIETERICH BUXTEHUDE by Ron James Anderson ______________________________ Copyright © Ron James Anderson 2012 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2012 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Ron James Anderson entitled “The Arts of Persuasion: Musical Rhetoric in the Keyboard Genres of Dieterich Buxtehude," and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. _________________________________________________________Date: 6/25/12 Rex Woods _________________________________________________________ Date: 6/25/12 Paula Fan _________________________________________________________ Date: 6/25/12 Tannis Gibson Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copy of the document to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this document prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the requirement.