|||GET||| Ancient Macedonia 1St Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11Th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA an Ancient City in Greece, the Capital of Laconia and the Most Powerful State of the Peloponnese

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA AN ancient city in Greece, the capital of Laconia and the most powerful state of the Peloponnese. The city lay at the northern end of the central Laconian plain, on the right bank of the river Eurotas, a little south of the point where it is joined by its largest tributary, the Oenus (mount Kelefina). The site is admirably fitted by nature to guard the only routes by which an army can penetrate Laconia from the land side, the Oenus and Eurotas valleys leading from Arcadia, its northern neighbour, and the Langada Pass over Mt Taygetus connecting Laconia and Messenia. At the same time its distance from the sea-Sparta is 27 m. from its seaport, Gythium, made it invulnerable to a maritime attack. I.-HISTORY Prehistoric Period.-Tradition relates that Sparta was founded by Lacedaemon, son of Zeus and Taygete, who called the city after the name of his wife, the daughter of Eurotas. But Amyclae and Therapne (Therapnae) seem to have been in early times of greater importance than Sparta, the former a Minyan foundation a few miles to the south of Sparta, the latter probably the Achaean capital of Laconia and the seat of Menelaus, Agamemnon's younger brother. Eighty years after the Trojan War, according to the traditional chronology, the Dorian migration took place. A band of Dorians united with a body of Aetolians to cross the Corinthian Gulf and invade the Peloponnese from the northwest. The Aetolians settled in Elis, the Dorians pushed up to the headwaters of the Alpheus, where they divided into two forces, one of which under Cresphontes invaded and later subdued Messenia, while the other, led by Aristodemus or, according to another version, by his twin sons Eurysthenes and Procles, made its way down the Eurotas were new settlements were formed and gained Sparta, which became the Dorian capital of Laconia. -

Ebook Download Greek Art 1St Edition

GREEK ART 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Nigel Spivey | 9780714833682 | | | | | Greek Art 1st edition PDF Book No Date pp. Fresco of an ancient Macedonian soldier thorakitai wearing chainmail armor and bearing a thureos shield, 3rd century BC. This work is a splendid survey of all the significant artistic monuments of the Greek world that have come down to us. They sometimes had a second story, but very rarely basements. Inscription to ffep, else clean and bright, inside and out. The Erechtheum , next to the Parthenon, however, is Ionic. Well into the 19th century, the classical tradition derived from Greece dominated the art of the western world. The Moschophoros or calf-bearer, c. Red-figure vases slowly replaced the black-figure style. Some of the best surviving Hellenistic buildings, such as the Library of Celsus , can be seen in Turkey , at cities such as Ephesus and Pergamum. The Distaff Side: Representing…. Chryselephantine Statuary in the Ancient Mediterranean World. The Greeks were quick to challenge Publishers, New York He and other potters around his time began to introduce very stylised silhouette figures of humans and animals, especially horses. Add to Basket Used Hardcover Condition: g to vg. The paint was frequently limited to parts depicting clothing, hair, and so on, with the skin left in the natural color of the stone or bronze, but it could also cover sculptures in their totality; female skin in marble tended to be uncoloured, while male skin might be a light brown. After about BC, figures, such as these, both male and female, wore the so-called archaic smile. -

This Is the Social and Religious Background Against Which The

BOOK REVIEWS 183 This is the social and religious background against which the accusation of ‘ac knowledging new deities’, brought against Socrates in 399 B.C., makes its appear ance. As Ρ. has shown, this accusation as such cannot be regarded as sufficient justifi cation for the trial. In spite of the general negative attitude on the part of the state, individuals did in practice ‘introduce new gods’ with some freedom, and by no means every case of such unauthorized religious innovation was prosecuted by the state. Socrates’ prosecution for kainotheism was in fact ‘only a counterpoise to that other and much more damning one of “not acknowledging the gods the city believes in.” And it was as a priestess in what we have called an “elective” cult, a “leader of lawless revel-bands of men and women”, that Phryne was attacked’ (pp. 216-17). That is to say, it was above all what was grasped by the Athenians as the antisocial character of the religious activities of Socrates and Phryne rather than the issue of ‘theological orthodoxy’ as such that brought both to trial. To be sure, the phenomenon which Ρ. calls ‘the totalitarian side of the classical city and its religion’ (p. 50) (‘communitarian’ seems to be a better term) was not a fifth-century Athenian invention. It can be discerned already in the legislative activi ties of Solon, and it was far from unfamiliar to other city-states of Archaic and Classi cal Greece. Yet, as Ρ. himself puts it, ‘The great attraction of studying the religion of classical Athens is not so much that it is either Athenian or classical a? that it can indeed be studied, in some detail’ (p. -

Parthenon 1 Parthenon

Parthenon 1 Parthenon Parthenon Παρθενών (Greek) The Parthenon Location within Greece Athens central General information Type Greek Temple Architectural style Classical Location Athens, Greece Coordinates 37°58′12.9″N 23°43′20.89″E Current tenants Museum [1] [2] Construction started 447 BC [1] [2] Completed 432 BC Height 13.72 m (45.0 ft) Technical details Size 69.5 by 30.9 m (228 by 101 ft) Other dimensions Cella: 29.8 by 19.2 m (98 by 63 ft) Design and construction Owner Greek government Architect Iktinos, Kallikrates Other designers Phidias (sculptor) The Parthenon (Ancient Greek: Παρθενών) is a temple on the Athenian Acropolis, Greece, dedicated to the Greek goddess Athena, whom the people of Athens considered their patron. Its construction began in 447 BC and was completed in 438 BC, although decorations of the Parthenon continued until 432 BC. It is the most important surviving building of Classical Greece, generally considered to be the culmination of the development of the Doric order. Its decorative sculptures are considered some of the high points of Greek art. The Parthenon is regarded as an Parthenon 2 enduring symbol of Ancient Greece and of Athenian democracy and one of the world's greatest cultural monuments. The Greek Ministry of Culture is currently carrying out a program of selective restoration and reconstruction to ensure the stability of the partially ruined structure.[3] The Parthenon itself replaced an older temple of Athena, which historians call the Pre-Parthenon or Older Parthenon, that was destroyed in the Persian invasion of 480 BC. Like most Greek temples, the Parthenon was used as a treasury. -

Ancient Greek Painting and Mosaics in Macedonia

ANCIENT GREEK PAINTING AND MOSAICS IN MACEDONIA All the manuals of Greek Art state that ancient Greek paintinG has been destroyed almost completely. Philological testimony, on the other hand, how ever rich, does no more than confirm the great loss. Vase painting affirms how skilful were the artisans in their drawings although it cannot replace the lost large paintinG compositions. Later wall-paintings of Roman towns such as Pompeii or Herculaneum testifying undoubted Greek or Hellenistic influ ence, enable us to have a glimpse of what the art of paintinG had achieved in Greece. Nevertheless, such paintings are chronologically too far removed from their probable Greek models for any accurate assessment to be made about the degree of dependence or the difference in quality they may have had between them. Archaeological investigation, undaunted, persists in revealing methodi cally more and more monuments that throw light into previously dark areas of the ancient world. Macedonia has always been a glorious name in later Greek history, illumined by the amazing brilliance of Alexander the Great. Yet knowledge was scarce about life in Macedonian towns where had reigned the ancestors and the descendants of that unique king, and so was life in many other Greek towns situated on the shores of the northern Aegean Sea. It is not many years ago, since systematic investigation began in these areas and we are still at the initial stage; but results are already very important, es pecially as they give the hope that we shall soon be able to reveal unknown folds of the Greek world in a district which has always been prominent in the his torical process of Hellenism. -

Influence of Science on Ancient Greek Sculptures

www.idosr.org Ahmed ©IDOSR PUBLICATIONS International Digital Organization for Scientific Research ISSN: 2579-0765 IDOSR JOURNAL OF CURRENT ISSUES IN SOCIAL SCIENCES 6(1): 45-49, 2020. Influence of Science on Ancient Greek Sculptures Ahmed Wahid Yusuf Department of Museum Studies, Menoufia University, Egypt. ABSTRACT The Greeks made major contributions to math and science. We owe our basic ideas about geometry and the concept of mathematical proofs to ancient Greek mathematicians such as Pythagoras, Euclid, and Archimedes. Some of the first astronomical models were developed by Ancient Greeks trying to describe planetary movement, the Earth’s axis, and the heliocentric system a model that places the Sun at the center of the solar system. The sculpture of ancient Greece is the main surviving type of fine ancient Greek art as, with the exception of painted ancient Greek pottery, almost no ancient Greek painting survives. The research further shows the influence science has in the ancient Greek sculptures. Keywords: Greek, Sculpture, Astronomers, Pottery. INTRODUCTION The sculpture of ancient Greece is the of the key points of Ancient Greek main surviving type of fine ancient Greek philosophy was the role of reason and art as, with the exception of painted inquiry. It emphasized logic and ancient Greek pottery, almost no ancient championed the idea of impartial, rational Greek painting survives. Modern observation of the natural world. scholarship identifies three major stages The Greeks made major contributions to in monumental sculpture in bronze and math and science. We owe our basic ideas stone: the Archaic (from about 650 to 480 about geometry and the concept of BC), Classical (480-323) and Hellenistic mathematical proofs to ancient Greek [1]. -

Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2011 (EBGR 2011)

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 27 | 2014 Varia Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2011 (EBGR 2011) Angelos Chaniotis Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/2266 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.2266 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 November 2014 Number of pages: 321-378 ISBN: 978-2-87562-055-2 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Angelos Chaniotis, « Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2011 (EBGR 2011) », Kernos [Online], 27 | 2014, Online since 01 October 2016, connection on 15 September 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/kernos/2266 This text was automatically generated on 15 September 2020. Kernos Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2011 (EBGR 2011) 1 Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2011 (EBGR 2011) Angelos Chaniotis 1 The 24th issue of the Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion presents epigraphic publications of 2011 and additions to earlier issues (publications of 2006–2010). Publications that could not be considered here, for reasons of space, will be presented in EBGR 2012. They include two of the most important books of 2011: N. PAPAZARKADAS’ Sacred and Public Land in Ancient Athens, Oxford 2011 and H.S. VERSNEL’s Coping with the Gods: Wayward Readings in Greek Theology, Leiden 2011. 2 A series of new important corpora is included in this issue. Two new IG volumes present the inscriptions of Eastern Lokris (119) and the first part of the inscriptions of Kos (21); the latter corpus is of great significance for the study of Greek religion, as it contains a large number of cult regulations; among the new texts, we single out the ‘sacred law of the tribe of the Elpanoridai’ in Halasarna. -

Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art 7-1-2000 Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures] J.L. Benson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Benson, J.L., "Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures]" (2000). Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements. 1. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cover design by Jeff Belizaire About this book This is one part of the first comprehensive study of the development of Greek sculpture and painting with the aim of enriching the usual stylistic-sociological approaches through a serious, disciplined consideration of the basic Greek scientific orientation to the world. This world view, known as the Four Elements Theory, came to specific formulation at the same time as the perfected contrapposto of Polykleitos and a concern with the four root colors in painting (Polygnotos). All these factors are found to be intimately intertwined, for, at this stage of human culture, the spheres of science and art were not so drastically differentiated as in our era. The world of the four elements involved the concepts of polarity and complementarism at every level. -

Copyrighted Material

9781405129992_6_ind.qxd 16/06/2009 12:11 Page 203 Index Acanthus, 130 Aetolian League, 162, 163, 166, Acarnanians, 137 178, 179 Achaea/Achaean(s), 31–2, 79, 123, Agamemnon, 51 160, 177 Agasicles (king of Sparta), 95 Achaean League: Agis IV and, agathoergoi, 174 166; as ally of Rome, 178–9; Age grades: see names of individual Cleomenes III and, 175; invasion grades of Laconia by, 177; Nabis and, Agesilaus (ephor), 166 178; as protector of perioecic Agesilaus II (king of Sparta), cities, 179; Sparta’s membership 135–47; at battle of Mantinea in, 15, 111, 179, 181–2 (362 B.C.E.), 146; campaign of, in Achaean War, 182 Asia Minor, 132–3, 136; capture acropolis, 130, 187–8, 192, 193, of Phlius by, 138; citizen training 194; see also Athena Chalcioecus, system and, 135; conspiracies sanctuary of after battle of Leuctra and, 144–5, Acrotatus (king of Sparta), 163, 158; conspiracy of Cinadon 164 and, 135–6; death of, 147; Acrotatus, 161 Epaminondas and, 142–3; Actium, battle of, 184 execution of women by, 168; Aegaleus, Mount, 65 foreign policy of, 132, 139–40, Aegiae (Laconian), 91 146–7; gift of, 101; helots and, Aegimius, 22 84; in Boeotia, 141; in Thessaly, Aegina (island)/Aeginetans: Delian 136; influence of, at Sparta, 142; League and,COPYRIGHTED 117; Lysander and, lameness MATERIAL of, 135; lance of, 189; 127, 129; pro-Persian party on, Life of, by Plutarch, 17; Lysander 59, 60; refugees from, 89 and, 12, 132–3; as mercenary, Aegospotami, battle of, 128, 130 146, 147; Phoebidas affair and, Aeimnestos, 69 102, 139; Spartan politics and, Aeolians, -

AT 2005 ART of ANCIENT GREECE (Previously at 2005 Art and Architecture of Ancient Greece)

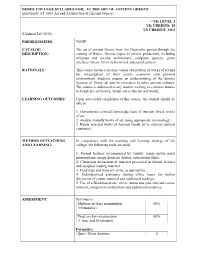

DEREE COLLEGE SYLLABUS FOR: AT 2005 ART OF ANCIENT GREECE (previously AT 2005 Art and Architecture of Ancient Greece) – UK LEVEL 4 UK CREDITS: 15 US CREDITS: 3/0/3 (Updated Fall 2015) PREREQUISITES: NONE CATALOG The art of ancient Greece from the Geometric period through the DESCRIPTION: coming of Rome. Diverse types of artistic production, including religious and secular architecture, sculpture, pottery, grave artefacts. Greek Art in its historical and social context. RATIONALE: This course focuses on close visual observation of works of art and the investigation of their social, economic and political environment. Students acquire an understanding of the distinct features of Greek art and its relevance to other ancient cultures. The course is addressed to any student wishing to continue studies in Greek art, art history, visual arts or the ancient world. LEARNING OUTCOMES: Upon successful completion of this course, the student should be able to: 1. Demonstrate a broad knowledge base of Ancient Greek works of art; 2. Analyse visually works of art, using appropriate terminology; 3. Relate selected works of Ancient Greek art to relevant cultural context(s). METHOD OFTEACHING In congruence with the teaching and learning strategy of the AND LEARNING: college, the following tools are used: 1. Formal lectures accompanied by visuals: image power point presentations; image database Artstor; educational films. 2. Classroom discussion of material presented in formal lectures and assigned reading material. 3. Field trips and museum visits, as appropriate. 4. Individualized assistance during office hours for further discussion of course material and additional readings. 5. Use of a Blackboard site, where instructors post relevant course material, assignment instructions and additional resources. -

Beauty in Ancient Greek Art: an Introduction

BEAUTY IN ANCIENT GREEK ART: AN INTRODUCTION Translate each term/expression about body, sculpture, ancient greek clothing. forearm / upper arm: ………………………………. (large scale / life-size) sculpture: ………………………………. palm: ………………………………. sculpture carved in the round: ………………………………. hairstyle: ………………………………. statue (equestrian / votive): ………………………………. braid: ………………………………. half-length / full-length portrait/figure: ……………………… fingers: ………………………………. …………………………………………………………………………………….. wrist: ………………………………. relief (bas-relief / high-relief): ………………………………. bosom: ………………………………. stele): ………………………………. bosom / chest: ………………………………. neck: ………………………………. marble: ………………………………. lips: ………………………………. bronze: ………………………………. cheekbones: ………………………………. gold: ………………………………. eyelids: ………………………………. silver: ………………………………. eyelashes: ………………………………. wood: ………………………………. chin: ………………………………. plaster: ………………………………. back: ………………………………. clay: ………………………………. shoulders: ………………………………. stone (dressed stone): ………………………………. womb / abdomen: ………………………………. terracotta: ………………………………. navel: ………………………………. wax: ………………………………. leg: ………………………………. foot: ………………………………. to sculpt / carve: ………………………………. ankle: ………………………………. to woodcarve: ………………………………. navel: ………………………………. to rough-hew: ………………………………. knee: ………………………………. to polish/to smooth: ………………………………. sculptor: ………………………………. carver: ………………………………. sandals: ………………………………. peplos / peplum: ………………………………. cloak / hymation: ………………………………. tunic / chiton: ………………………………. patch: ………………………………. linen: ………………………………. wool: ………………………………. to be wrapped in: ………………………………. to -

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan LINDA JANE PIPER 1967

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 66-15,122 PIPER, Linda Jane, 1935- A HISTORY OF SPARTA: 323-146 B.C. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1966 History, ancient University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan LINDA JANE PIPER 1967 All Rights Reserved A HISTORY OF SPARTA: 323-1^6 B.C. DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Linda Jane Piper, A.B., M.A. The Ohio State University 1966 Approved by Adviser Department of History PREFACE The history of Sparta from the death of Alexander in 323 B.C; to the destruction of Corinth in 1^6 B.C. is the history of social revolution and Sparta's second rise to military promi nence in the Peloponnesus; the history of kings and tyrants; the history of Sparta's struggle to remain autonomous in a period of amalgamation. It is also a period in Sparta's history too often neglected by historians both past and present. There is no monograph directly concerned with Hellenistic Sparta. For the most part, this period is briefly and only inci dentally covered in works dealing either with the whole history of ancient Sparta, or simply as a part of Hellenic or Hellenistic 1 2 history in toto. Both Pierre Roussel and Eug&ne Cavaignac, in their respective surveys of Spartan history, have written clear and concise chapters on the Hellenistic period. Because of the scope of their subject, however, they were forced to limit them selves to only the most important events and people of this time, and great gaps are left in between.