Beauty in Ancient Greek Art: an Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parthenon 1 Parthenon

Parthenon 1 Parthenon Parthenon Παρθενών (Greek) The Parthenon Location within Greece Athens central General information Type Greek Temple Architectural style Classical Location Athens, Greece Coordinates 37°58′12.9″N 23°43′20.89″E Current tenants Museum [1] [2] Construction started 447 BC [1] [2] Completed 432 BC Height 13.72 m (45.0 ft) Technical details Size 69.5 by 30.9 m (228 by 101 ft) Other dimensions Cella: 29.8 by 19.2 m (98 by 63 ft) Design and construction Owner Greek government Architect Iktinos, Kallikrates Other designers Phidias (sculptor) The Parthenon (Ancient Greek: Παρθενών) is a temple on the Athenian Acropolis, Greece, dedicated to the Greek goddess Athena, whom the people of Athens considered their patron. Its construction began in 447 BC and was completed in 438 BC, although decorations of the Parthenon continued until 432 BC. It is the most important surviving building of Classical Greece, generally considered to be the culmination of the development of the Doric order. Its decorative sculptures are considered some of the high points of Greek art. The Parthenon is regarded as an Parthenon 2 enduring symbol of Ancient Greece and of Athenian democracy and one of the world's greatest cultural monuments. The Greek Ministry of Culture is currently carrying out a program of selective restoration and reconstruction to ensure the stability of the partially ruined structure.[3] The Parthenon itself replaced an older temple of Athena, which historians call the Pre-Parthenon or Older Parthenon, that was destroyed in the Persian invasion of 480 BC. Like most Greek temples, the Parthenon was used as a treasury. -

Ancient Greek Painting and Mosaics in Macedonia

ANCIENT GREEK PAINTING AND MOSAICS IN MACEDONIA All the manuals of Greek Art state that ancient Greek paintinG has been destroyed almost completely. Philological testimony, on the other hand, how ever rich, does no more than confirm the great loss. Vase painting affirms how skilful were the artisans in their drawings although it cannot replace the lost large paintinG compositions. Later wall-paintings of Roman towns such as Pompeii or Herculaneum testifying undoubted Greek or Hellenistic influ ence, enable us to have a glimpse of what the art of paintinG had achieved in Greece. Nevertheless, such paintings are chronologically too far removed from their probable Greek models for any accurate assessment to be made about the degree of dependence or the difference in quality they may have had between them. Archaeological investigation, undaunted, persists in revealing methodi cally more and more monuments that throw light into previously dark areas of the ancient world. Macedonia has always been a glorious name in later Greek history, illumined by the amazing brilliance of Alexander the Great. Yet knowledge was scarce about life in Macedonian towns where had reigned the ancestors and the descendants of that unique king, and so was life in many other Greek towns situated on the shores of the northern Aegean Sea. It is not many years ago, since systematic investigation began in these areas and we are still at the initial stage; but results are already very important, es pecially as they give the hope that we shall soon be able to reveal unknown folds of the Greek world in a district which has always been prominent in the his torical process of Hellenism. -

Influence of Science on Ancient Greek Sculptures

www.idosr.org Ahmed ©IDOSR PUBLICATIONS International Digital Organization for Scientific Research ISSN: 2579-0765 IDOSR JOURNAL OF CURRENT ISSUES IN SOCIAL SCIENCES 6(1): 45-49, 2020. Influence of Science on Ancient Greek Sculptures Ahmed Wahid Yusuf Department of Museum Studies, Menoufia University, Egypt. ABSTRACT The Greeks made major contributions to math and science. We owe our basic ideas about geometry and the concept of mathematical proofs to ancient Greek mathematicians such as Pythagoras, Euclid, and Archimedes. Some of the first astronomical models were developed by Ancient Greeks trying to describe planetary movement, the Earth’s axis, and the heliocentric system a model that places the Sun at the center of the solar system. The sculpture of ancient Greece is the main surviving type of fine ancient Greek art as, with the exception of painted ancient Greek pottery, almost no ancient Greek painting survives. The research further shows the influence science has in the ancient Greek sculptures. Keywords: Greek, Sculpture, Astronomers, Pottery. INTRODUCTION The sculpture of ancient Greece is the of the key points of Ancient Greek main surviving type of fine ancient Greek philosophy was the role of reason and art as, with the exception of painted inquiry. It emphasized logic and ancient Greek pottery, almost no ancient championed the idea of impartial, rational Greek painting survives. Modern observation of the natural world. scholarship identifies three major stages The Greeks made major contributions to in monumental sculpture in bronze and math and science. We owe our basic ideas stone: the Archaic (from about 650 to 480 about geometry and the concept of BC), Classical (480-323) and Hellenistic mathematical proofs to ancient Greek [1]. -

Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2011 (EBGR 2011)

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 27 | 2014 Varia Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2011 (EBGR 2011) Angelos Chaniotis Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/2266 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.2266 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 November 2014 Number of pages: 321-378 ISBN: 978-2-87562-055-2 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Angelos Chaniotis, « Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2011 (EBGR 2011) », Kernos [Online], 27 | 2014, Online since 01 October 2016, connection on 15 September 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/kernos/2266 This text was automatically generated on 15 September 2020. Kernos Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2011 (EBGR 2011) 1 Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2011 (EBGR 2011) Angelos Chaniotis 1 The 24th issue of the Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion presents epigraphic publications of 2011 and additions to earlier issues (publications of 2006–2010). Publications that could not be considered here, for reasons of space, will be presented in EBGR 2012. They include two of the most important books of 2011: N. PAPAZARKADAS’ Sacred and Public Land in Ancient Athens, Oxford 2011 and H.S. VERSNEL’s Coping with the Gods: Wayward Readings in Greek Theology, Leiden 2011. 2 A series of new important corpora is included in this issue. Two new IG volumes present the inscriptions of Eastern Lokris (119) and the first part of the inscriptions of Kos (21); the latter corpus is of great significance for the study of Greek religion, as it contains a large number of cult regulations; among the new texts, we single out the ‘sacred law of the tribe of the Elpanoridai’ in Halasarna. -

Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art 7-1-2000 Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures] J.L. Benson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Benson, J.L., "Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures]" (2000). Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements. 1. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cover design by Jeff Belizaire About this book This is one part of the first comprehensive study of the development of Greek sculpture and painting with the aim of enriching the usual stylistic-sociological approaches through a serious, disciplined consideration of the basic Greek scientific orientation to the world. This world view, known as the Four Elements Theory, came to specific formulation at the same time as the perfected contrapposto of Polykleitos and a concern with the four root colors in painting (Polygnotos). All these factors are found to be intimately intertwined, for, at this stage of human culture, the spheres of science and art were not so drastically differentiated as in our era. The world of the four elements involved the concepts of polarity and complementarism at every level. -

Archaeology and Classics

CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JANUARY 2 – 5, 2014 WELCOME TO CHICAGO! Dear AIA Members and Colleagues, Welcome to Chicago for the 115th Annual Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America. This year’s meeting combines an exciting program presenting cutting-edge research with the unique opportunity to socialize, network, and relax with thousands of your peers from the US, Canada, and more than 30 foreign countries. Appropriately for an urban venue settled in the 19th century by ethnic Europeans, this year’s meeting will feature several sessions on East European archaeology. And sessions devoted to heritage and preservation and digital methodologies in archaeology touch upon increasingly central concerns in the discipline. Back by popular demand are the undergraduate paper session and the Lightning Session. We are indebted to Trustee Michael L. Galaty and the Program for the Annual Meeting Committee that he chairs for fashioning such a stimulating program. Table of Contents Some of the other highlights of this year’s meeting include: General Information ......4-5 Opening Night Lecture and Reception (Thursday, 6:00–9:00 pm) Program-at-a-Glance 10-11 We kick off the meeting with a public lecture by Dr. Garrett Fagan, Professor of Ancient History at Penn State University. In “How to Stage a Bloodbath: Theatricality and Artificiality at the Roman Arena” Fagan explores Exhibitors .................. 12-13 the theatrical aspects of Roman arena games – the stage sets, equipment of the fighters, etc–that created an artificial landscape in which the violence of the spectacle was staged. Fagan will also consider what these Thursday, January 2 features tell us about Roman attitudes toward the violence of the games, and how spectators reacted to them Day-at-a-Glance ..........14 psychologically (Thursday, 6 pm). -

AT 2005 ART of ANCIENT GREECE (Previously at 2005 Art and Architecture of Ancient Greece)

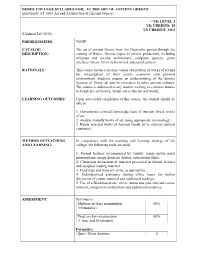

DEREE COLLEGE SYLLABUS FOR: AT 2005 ART OF ANCIENT GREECE (previously AT 2005 Art and Architecture of Ancient Greece) – UK LEVEL 4 UK CREDITS: 15 US CREDITS: 3/0/3 (Updated Fall 2015) PREREQUISITES: NONE CATALOG The art of ancient Greece from the Geometric period through the DESCRIPTION: coming of Rome. Diverse types of artistic production, including religious and secular architecture, sculpture, pottery, grave artefacts. Greek Art in its historical and social context. RATIONALE: This course focuses on close visual observation of works of art and the investigation of their social, economic and political environment. Students acquire an understanding of the distinct features of Greek art and its relevance to other ancient cultures. The course is addressed to any student wishing to continue studies in Greek art, art history, visual arts or the ancient world. LEARNING OUTCOMES: Upon successful completion of this course, the student should be able to: 1. Demonstrate a broad knowledge base of Ancient Greek works of art; 2. Analyse visually works of art, using appropriate terminology; 3. Relate selected works of Ancient Greek art to relevant cultural context(s). METHOD OFTEACHING In congruence with the teaching and learning strategy of the AND LEARNING: college, the following tools are used: 1. Formal lectures accompanied by visuals: image power point presentations; image database Artstor; educational films. 2. Classroom discussion of material presented in formal lectures and assigned reading material. 3. Field trips and museum visits, as appropriate. 4. Individualized assistance during office hours for further discussion of course material and additional readings. 5. Use of a Blackboard site, where instructors post relevant course material, assignment instructions and additional resources. -

Dionysiac Art and Pastoral Escapism

Alpenglow: Binghamton University Undergraduate Journal of Research and Creative Activity Volume 6 Number 1 (2020) Article 4 12-1-2020 Dionysiac Art and Pastoral Escapism Casey Roth Binghamton University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/alpenglowjournal Recommended Citation Roth, C. (2020). Dionysiac Art and Pastoral Escapism. Alpenglow: Binghamton University Undergraduate Journal of Research and Creative Activity, 6(1). Retrieved from https://orb.binghamton.edu/ alpenglowjournal/vol6/iss1/4 This Academic Paper is brought to you for free and open access by The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Alpenglow: Binghamton University Undergraduate Journal of Research and Creative Activity by an authorized editor of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. Casey Roth Dionysiac Art and Pastoral Escapism The pastoral lifestyle was appealing to many people in the Hellenistic and Roman world, as it provided an escape from the stresses of the city.1 This longing to flee the materialistic urban centers was reflected in art and literature, in which Dionysiac figures, such as satyrs or even herdsmen, were represented and described in this idealized environment and provided viewers with a sense of being carefree. Dionysiac elements in art and literature represented this escape from the chaotic city, overcoming boundaries to allow one to welcome a utopia.2 Not only were boundaries overcome in both a worldly and geographic sense, but also identity was challenged. As a result of escaping the city through pastoralism, one could abandon their identity as a civilian for an existence defined by pastoral bliss.3 Pastoralism was associated with an idyllic landscape and can act as an escape from reality. -

Ancient Greek Art Teacher Resource

Image Essay #2 Beak-Spouted Jug ca. 1425 B.C. Mycenaean Glazed ceramic Height: 10 1/4” WAM Accession Number: 48.2098 LOOKING AT THE OBJECT WITH STUDENTS This terracotta clay jug with a long beak-like spout is decorated in light-colored glaze with a series of nautilus- inspired shell patterns. The abstract design on the belly of the jug alludes to a sea creature’s tentacles spreading across the vase emphasizing the shape and volume of the vessel. A wavy leaf design on the vase’s shoulder fur- ther accentuates the marine-motif, with the curves of the leaves referring to the waves of the sea. Around the han- dle and spout are contour lines rendered in brown glaze. BACKGROUND INFORMATION Long before Classical Greece flourished in the 5th century B.C., two major civilizations dominated the Aegean in the 3rd and 2nd millennia B.C.: the Minoans on Crete and the Mycenaeans on the Greek mainland. The prosper- ous Minoans, named after the legendary King Minos, ruled over the sea and built rich palaces on Crete. Their art is characterized by lively scenes depicting fanciful plants and (sea) animals. By the middle of the 2nd millennium B.C., Mycenaean culture started to dominate the Aegean. It is known for its mighty citadels at Mycenae and else- where, its impressive stone tombs, and its extensive trading throughout the Mediterranean world. Beak-spouted jugs were popular in both the Minoan and Mycenaean cultures. They held wine or water, and were often placed in tombs as gifts to the deceased. -

Ancient Macedonians

Ancient Macedonians This article is about the native inhabitants of the historical kingdom of Macedonia. For the modern ethnic Greek people from Macedonia, Greece, see Macedonians (Greeks). For other uses, see Ancient Macedonian (disambiguation) and Macedonian (disambiguation). From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia ANCIENT MACEDONIANS ΜΑΚΕΔΌΝΕΣ Stag Hunt Mosaic, 4th century BC Languages. Ancient Macedonian, then Attic Greek, and later Koine Greek Religion. ancient Greek religion The Macedonians (Greek: Μακεδόνες, Makedónes) were an ancient tribe that lived on the alluvial plain around the rivers Haliacmonand lower Axios in the northeastern part of mainland Greece. Essentially an ancient Greek people,[1] they gradually expanded from their homeland along the Haliacmon valley on the northern edge of the Greek world, absorbing or driving out neighbouring non-Greek tribes, primarily Thracian and Illyrian.[2][3] They spoke Ancient Macedonian, a language closely related to Ancient Greek, perhaps a dialect, although the prestige language of the region was at first Attic and then Koine Greek.[4] Their religious beliefs mirrored those of other Greeks, following the main deities of the Greek pantheon, although the Macedonians continued Archaic burial practices that had ceased in other parts of Greece after the 6th century BC. Aside from the monarchy, the core of Macedonian society was its nobility. Similar to the aristocracy of neighboring Thessaly, their wealth was largely built on herding horses and cattle. Although composed of various clans, the kingdom of Macedonia, established around the 8th century BC, is mostly associated with the Argead dynasty and the tribe named after it. The dynasty was allegedly founded by Perdiccas I, descendant of the legendary Temenus of Argos, while the region of Macedon perhaps derived its name from Makedon, a figure of Greek mythology. -

Ancient Greek the Studiowith Architecture, Pottery & Sculpture ART HIST RY KIDS

Ancient Greek The Studiowith Architecture, Pottery & Sculpture ART HIST RY KIDS LET’S LOOK AGAIN It’s best to study architecture when you can actually visit the places and see things up close. It’s fun to look at things up high and down low... to see things from lots of different perspectives. Since we are looking at photographs of the architecture, we’ll need to pay especially close attention to what we see in the pictures. Here are a few different angles from the three build- ings we’re learning about this month. Do you notice anything new? Architecture offers us so much to look at and learn about. We’ll be focusing on one thing this week: columns. Make sure to look at the columns in each building, then write down or chat about your observations. The Parthenon Temple of Olympian Zeus The Erechtheion March 2019 | Week 2 1 Ancient Greek The Studiowith Architecture, Pottery & Sculpture ART HIST RY KIDS A TIMELINE OF GREEK ART Geometric Archaic Hellenistic Period Period Period 900-700 BCE 700-600 BCE 600-480 BCE 480-323 BCE 323-31 BCE Orientalizing Classical Period Period March 2019 | Week 2 2 Ancient Greek The Studiowith Architecture, Pottery & Sculpture ART HIST RY KIDS GREEK ARCHITECTURE If you’ve ever built a structure out of wooden blocks or legos, you’ve played with the idea of architec- ture. The Greeks took ideas about building that had already been around for centuries, and made them more decorative and extra fancy. Greek Architects were obsessed with beauty. The word arete is often used when art historians talk about Ancient Greek art and architecture, and it means: excellence. -

![(~4 ½” High, Limestone) [Fertility Statue] MESOPOTAMIA Sumerian: Female Head from Uruk, (Goddess Inanna?) (C](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3036/4-%C2%BD-high-limestone-fertility-statue-mesopotamia-sumerian-female-head-from-uruk-goddess-inanna-c-3523036.webp)

(~4 ½” High, Limestone) [Fertility Statue] MESOPOTAMIA Sumerian: Female Head from Uruk, (Goddess Inanna?) (C

ART HISTORY The Human 1 Figure throughout The Ages Paleolithic: Venus of Willendorf; Willendorf, Austria (c. 28,000 – 25,000 BC) (~4 ½” high, limestone) [fertility statue] MESOPOTAMIA Sumerian: Female Head from Uruk, (goddess Inanna?) (c. 3,200 – 3,000 BC) [Marble, Sculpture] (stolen from Baghdad Museum – found in someone’s back yard) Akkadian: Head of an Akkadian Ruler, from Nineveh, (c. 2,250 – 2,200 BC) [Bronze, Sculpture] Babylonian: Stele of Hammurabi, (c. 1,780 BC), Present day Iran [Babylonian Civic Code Marker] (basalt) Hammurabi: (1,792 – 1,750 BC) Babylon’s strongest king: centralized power in Mesopotamia Sumerian: Statuettes of Abu, from the Temple at Tell Asmar (c. 2,700 BC) Imagery: Abstraction, Realism Detail: Worshippers, (gypsum inlay with shell and black limestone) [Iraq Museum] Symbolism: The Four Evangelists Matthew John attribute: attribute: winged human eagle symbolizes: symbolizes: humanity, reason sky, heavens, spirit Mark attribute: Luke winged lion attribute: winged ox symbolizes: royalty, courage, symbolizes9: resurrection sacrifice, strength Assyrian: Lamassu, (winged, human-headed bull -citadel of Sargon II) (c. 720 - 705 BC), Present day Iraq (limestone) Assyrian: Ashurbanipal Hunting Lions, (c. 645 - 640 BC), Present day Iraq [Relief sculpture from the North Palace of Ashurbanipal] (gypsum) EGYPT front back Ancient Egyptian (Early Dynasty): Palette of King Narmer, (c. 3,000 - 2920 BC), (~2’ 1” high) [Egyptian eye makeup palette] (slate) Explanation of Palette of King Narmer The earliest example of the Egyptian style, which is called "Frontalism", can be seen in the Palette of Narmer which is considered to be an early blueprint of the formula of figure representation that was to rule Egyptian art for 3,000 years.The Palette of Narmer was originally used as a tablet to prepare eye makeup for protecting the eyes against sun glare and irritation.