National Academic Choir of Ukraine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES Composers

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers A-G KHAIRULLO ABDULAYEV (b. 1930, TAJIKISTAN) Born in Kulyab, Tajikistan. He studied composition at the Moscow Conservatory under Anatol Alexandrov. He has composed orchestral, choral, vocal and instrumental works. Sinfonietta in E minor (1964) Veronica Dudarova/Moscow State Symphony Orchestra ( + Poem to Lenin and Khamdamov: Day on a Collective Farm) MELODIYA S10-16331-2 (LP) (1981) LEV ABELIOVICH (1912-1985, BELARUS) Born in Vilnius, Lithuania. He studied at the Warsaw Conservatory and then at the Minsk Conservatory where he studied under Vasily Zolataryov. After graduation from the latter institution, he took further composition courses with Nikolai Miaskovsky at the Moscow Conservatory. He composed orchestral, vocal and chamber works. His other Symphonies are Nos. 1 (1962), 3 in B flat minor (1967) and 4 (1969). Symphony No. 2 in E minor (1964) Valentin Katayev/Byelorussian State Symphony Orchestra ( + Vagner: Suite for Symphony Orchestra) MELODIYA D 024909-10 (LP) (1969) VASIF ADIGEZALOV (1935-2006, AZERBAIJAN) Born in Baku, Azerbaijan. He studied under Kara Karayev at the Azerbaijan Conservatory and then joined the staff of that school. His compositional catalgue covers the entire range of genres from opera to film music and works for folk instruments. Among his orchestral works are 4 Symphonies of which the unrecorded ones are Nos. 1 (1958) and 4 "Segah" (1998). Symphony No. 2 (1968) Boris Khaikin/Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra (rec. 1968) ( + Piano Concertos Nos. 2 and 3, Poem Exaltation for 2 Pianos and Orchestra, Africa Amidst MusicWeb International Last updated: August 2020 Russian, Soviet & Post-Soviet Symphonies A-G Struggles, Garabagh Shikastasi Oratorio and Land of Fire Oratorio) AZERBAIJAN INTERNATIONAL (3 CDs) (2007) Symphony No. -

Compact Discs by 20Th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020

Compact Discs by 20th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020 Compact Discs Adams, John Luther, 1953- Become Desert. 1 CDs 1 DVDs $19.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2019 CA 21148 2 713746314828 Ludovic Morlot conducts the Seattle Symphony. Includes one CD, and one video disc with a 5.1 surround sound mix. http://www.tfront.com/p-476866-become-desert.aspx Canticles of The Holy Wind. $16.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2017 CA 21131 2 713746313128 http://www.tfront.com/p-472325-canticles-of-the-holy-wind.aspx Adams, John, 1947- John Adams Album / Kent Nagano. $13.98 New York: Decca Records ©2019 DCA B003108502 2 028948349388 Contents: Common Tones in Simple Time -- 1. First Movement -- 2. the Anfortas Wound -- 3. Meister Eckhardt and Quackie -- Short Ride in a Fast Machine. Nagano conducts the Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal. http://www.tfront.com/p-482024-john-adams-album-kent-nagano.aspx Ades, Thomas, 1971- Colette [Original Motion Picture Soundtrack]. $14.98 Lake Shore Records ©2019 LKSO 35352 2 780163535228 Music from the film starring Keira Knightley. http://www.tfront.com/p-476302-colette-[original-motion-picture-soundtrack].aspx Agnew, Roy, 1891-1944. Piano Music / Stephanie McCallum, Piano. $18.98 London: Toccata Classics ©2019 TOCC 0496 5060113444967 Piano music by the early 20th century Australian composer. http://www.tfront.com/p-481657-piano-music-stephanie-mccallum-piano.aspx Aharonian, Coriun, 1940-2017. Carta. $18.98 Wien: Wergo Records ©2019 WER 7374 2 4010228737424 The music of the late Uruguayan composer is performed by Ensemble Aventure and SWF-Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden. http://www.tfront.com/p-483640-carta.aspx Ahmas, Harri, 1957- Organ Music / Jan Lehtola, Organ. -

Pavel Lisitsian Discography by Richard Kummins

Pavel Lisitsian Discography By Richard Kummins e-mail: [email protected] Rev - 17 June 2014 Composer Selection Other artists Date Lang Record # The capital city of the country (Stolitsa Agababov rodin) 1956 Rus 78 USSR 41366 (1956) LP Melodiya 14305/6 (1964) LP Melodiya M10 45467/8 (1984) CD Russian Disc 15022 (1994) MP3 RMG 1637 (2005 - Song Listen, maybe, Op 49 #2 (Paslushai, byt Anthology Vol 1) Arensky mozhet) Andrei Mitnik, piano 1951 Rus MP3 RMG 1766 (2006) 78 USSR 14626 (1947) LP Vocal Record Collector's Armenian (trad) Armenian girls (Hayotz akhchikner) Matvei Sakharov, piano 1947 Arm Society 1992 Armenian girls (Hayotz akhchikner) LP Melodiya 45465/6 (1984) Armenian (trad) (arranged by Aleksandr Dolukhanian) Matvei Sakharov, piano 1948 Arm MP3 RMG 1766 (2006) Armenian girls (Hayotz akhchikner) 1960 (San LP New York Records PL 101 Armenian (trad) (arranged by Aleksandr Dolukhanian) Maro Ajemian, piano Francisco) Arm (1960) Crane (Groong) 1960 (San LP New York Records PL 101 Armenian (trad) (arranged by Aleksandr Dolukhanian) Maro Ajemian, piano Francisco) Arm (1960) Russian Folk Instrument Orchestra - Crane (Groong) Central TV and All-Union Radio LP Melodiya 45465/6 (1984) Armenian (trad) (arranged by Aleksandr Dolukhanian) - Vladimir Fedoseyev 1968 Arm MP3 RMG 1766 (2006) LP DKS 6228 (1955) Armenian (trad) Dogwood forest (Lyut kizil usta tvoi) Matvei Sakharov, piano 1955 Arm MP3 RMG 1766 (2006) Dream (Yeraz) (arranged by Aleksandr LP Melodiya 45465/6 (1984) Armenian (trad) Dolukhanian) Matvei Sakharov, piano 1948 Arm MP3 RMG -

TCHAIKOVSKY Liturgy of St

TCHAIKOVSKY Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom Nine Sacred Choruses Latvian Radio Choir Sigvards Kļava PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840–1893) Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, Op. 41 (1878) Liturgiya svyatogo Ioanna Zlatousta 1. After first Antiphon: Glory to the Father | Posle pervovo antifona: Slava Otsu i Sïnu 3:04 2 After the Little Entrance: Come, Let Us Worship | Posle malovo fhoda: Pridiite, poklonimsa 3:43 3. Cherubic Hymn | Heruvimskaya pesn: Izhe Heruvim 6:02 4. The Creed | Simvol verï 4:48 5. After the Creed: A Mercy of Peace | Posle Simvola verï: Milost mira 4:24 6. After the exclamation ‘Thine own of Thine…’: We Hymn to Thee |Posle vozglasheniya ”Tvoya ot Tvoih...”: Tebe poem 2:41 7. After the words ‘Especially for our most holy…’: Hymn to the Mother of God | Posle slov “Izriadno o presviatey...”: Dostoyno yest 3:26 8. The Lord’s Prayer: Our Father | Molitva Gospodnya: Otche nash 3:25 9. The Communion Hymn: Praise the Lord | Prichastnïy stih: Hvalite Gospoda 2:32 10. After the exclamation ‘In the fear of God…’: We have seen the True Light! | Posle vozglasheniya ”So strahom Bozhïim...”: Videhom svet istinï 3:26 Nine Sacred Choruses (1884–85) Devjati duhovno-muzykalnyh sotshinenij 11. Cherubic Hymn I | Heruvimskaya pesn I 6:05 12. Cherubic Hymn II | Heruvimskaya pesn II 5:51 13. Cherubic Hymn III | Heruvimskaya pesn III 6:01 14. We Hymn to Thee |Tebe poem 3:20 15. Hymn to the Mother of God | Dostoyno yest 3:03 16. Our Father | Otche nash 3:16 17. Blessed are They | Blazheni, yazhe ibral 3:23 18. -

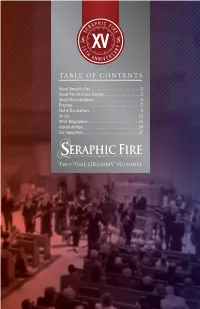

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS About Seraphic Fire . 4 About Patrick Dupré Quigley . .. 5 About Elena Sharkova . 6 Program . 7 Text & Translations . 8 Artists . 15 Artist Biographies . 16 Administration . 24 Our Supporters . 27 Two-Time GRAMMY® Nominee Oct 2017 Nov 2017 Dec 2017 Jan 2018 Feb 2018 Mar 2018 "After celebrating 15 years, this next season provides an eclectic musical journey through masterworks of cultural significance like Brahms’ timeless Liebeslieder Waltzes, as well as through high-quality under-performed music like David Lang's The Little Match Girl Passion. Our 16th Season continues to put South Florida at the center of artistic innovation with the country’s finest vocal artists performing history’s awe-inspiring repertoire." Apr 2018 May 2018 Patrick Dupré Quigley, Founder & Artistic Director Subscriptions Now on Sale! Subscribe at SeraphicFire.org or 305.285.9060 ABOUT SERAPHIC FIRE ABOUT PATRICK DUPRÉ QUIGLEY Led by Founder and Artistic Director Patrick Dupré appearance by conductor Elena Sharkova . The Quigley, Seraphic Fire brings top ensemble singers season also features collaborations with organist and instrumentalists from around the country to Nathan Laube and violinist Matthew Albert . perform repertoire ranging from Gregorian chant and Baroque masterpieces, to Mahler and newly Recognized as “one of the best excuses for commissioned works by this country’s leading living in Miami” (el Nuevo Herald) because of its composers . Two of the ensemble’s recordings, “vivid, sensitive performances” (The Washington Brahms: Ein Deutsches -

Developing the Young Dramatic Soprano Voice Ages 15-22 Is Approved in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of

DEVELOPING THE YOUNG DRAMATIC SOPRANO VOICE AGES 15-22 By Monica Ariane Williams Bachelor of Arts – Vocal Arts University of Southern California 1993 Master of Music – Vocal Arts University of Southern California 1995 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music College of Fine Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas December 2020 Copyright 2021 Monica Ariane Williams All Rights Reserved Dissertation Approval The Graduate College The University of Nevada, Las Vegas November 30, 2020 This dissertation prepared by Monica Ariane Williams entitled Developing the Young Dramatic Soprano Voice Ages 15-22 is approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music Alfonse Anderson, DMA. Kathryn Hausbeck Korgan, Ph.D. Examination Committee Chair Graduate College Dean Linda Lister, DMA. Examination Committee Member David Weiller, MM. Examination Committee Member Dean Gronemeier, DMA, JD. Examination Committee Member Joe Bynum, MFA. Graduate College Faculty Representative ii ABSTRACT This doctoral dissertation provides information on how to develop the young dramatic soprano, specifically through more concentrated focus on the breath. Proper breathing is considered the single most important skill a singer will learn, but its methodology continues to mystify multitudes of singers and voice teachers. Voice professionals often write treatises with a chapter or two devoted to breathing, whose explanations are extremely varied, complex or vague. Young dramatic sopranos, whose voices are unwieldy and take longer to develop are at a particular disadvantage for absorbing a solid vocal technique. First, a description, classification and brief history of the young dramatic soprano is discussed along with a retracing of breath methodologies relevant to the young dramatic soprano’s development. -

Complete Piano Music Rˇák

DVO COMPLETE PIANO MUSIC RˇÁK Inna Poroshina piano QUINTESSENCE · QUINTESSENZ · QUINTESSENZA · QUINAESENCIA · QUINTESSÊNCIA · QUINTESSENCE · QUINTESSENZ · QUINTESSENZA · QUINAESENCIA · QUINTESSÊNCIA Antonín Dvorˇák 1841-1904 Complete Piano Music Theme and Variations Op.36 (1876) Two Furiants Op.42 (1878) Six Mazurkas Op.56 1. Theme 1’21 26. No.1 in D major 5’33 51. No.1 2’50 76. No.4 in D minor, poco andante 2’46 2. Variation 1 1’09 27. No.2 in F major 7’38 52. No.2 2’28 77. No.5 in A minor, vivace 3’04 3. Variation 2 1’12 53. No.3 1’58 78. No.6 in B major, poco allegretto 2’56 4. Variation 3 2’56 Eight Waltzes Op.54 (1880) 54. No.4 2’57 79. No.7 in G flat major, poco lento 5. Variation 4 0’41 28. No.1 in A major 3’39 55. No.5 2’37 e grazioso 3’26 6. Variation 5 1’00 29. No.2 in A minor 4’05 56. No.6 2’35 80. No.8 in B minor, poco andante 3’22 7. Variation 6 1’36 30. No.3 in C sharp minor 2’55 8. Variation 7 0’58 31. No.4 in D flat major 2’52 57. Moderato in A major B.116 2’10 81. Dumka, Op.12/1 (1884) 4’00 9. Variation 8 3’53 32. No.5 in B flat major 3’00 33. No.6 in F major 5’05 58. Question, B.128a 0’27 82. -

15° Festival & Concorso Corale Internazionale Riva Del Garda & Arco

15° Festival & Concorso Corale Internazionale 15th International Choir Festival & Competition 25 - 29 Marzo · March 2018 Riva del Garda & Arco Concorso Corale Musica Eterna Roma Internazionale July 11 - 15, 2018 March 25 - 29, 2018 July 10 - 14, 2019 April 5 - 9, 2020 July 2020 Riva del Garda & Arco | ITALY Rome | ITALY Venezia in Musica Spring Edition Beira Interior April 28 - May 2, 2018 October 3 - 7, 2018 April 28 - May 2, 2019 October 2020 April 29 - May 3, 2020 Fundão | PORTUGAL Caorle & Venice | ITALY 25 - 29 Marzo · March 2018 Riva del Garda & Arco Laurea Mundi Budapest & Venezia in Musica Choral Celebration Autumn Edition May 18 - 22, 2018 October 25 - 28, 2018 May 2020 October 2020 Organizzatore · Organiser Budapest | HUNGARY Sacile & Venice | ITALY PER MUSICAM AD ASTRA Budapest International International Copernicus Choir Choir Competition Festival & Competition April 14 - 18, 2019 June 27 - July 1, 2018 March 28 - April 1, 2021 June 29 - July 3, 2019 Budapest | Hungary Toruń | POLAND Patrocinio · Patronage Salzburg International Choral Comune di Riva del Garda SING BERLIN! Celebration & Competition Federazione Cori del Trentino July 4 - 8, 2018 June 19 - 24, 2019 July 2020 June 2021 Berlin | GERMANY Salzburg | AUSTRIA Direzione artistica · Artistic directors Gábor Hollerung (Ungheria · Hungary) Enrico Miaroma (Italia · Italy) In... Canto sul Garda October 12 - 16, 2019 October 2021 Direttrice del progetto · Project Director Riva del Garda & Arco | ITALY Piroska Horváth (Ungheria · Hungary) Our International in collaborazione con · in cooperation with Choir Festivals & Competitions Indice · Index Cori Partecipanti · Participating Choirs Jitřenka G1 & G2 Männerchorensemble „vocawäller“ B2 Cori Participanti · Participating Choirs .............................................. 5 Südwestpfälzer Kinderchor Münchweiler G1 Vokalkreis des Telemann-Konservatoriums Magdeburg A3 & S3 Saluti · Greetings ................................................................................ -

Dissertation First Pages

Dissertation in Music Performance by Joachim C. Angster A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music: Performance) in the University of Michigan 2020 Dissertation Committee: Assistant Professor Caroline Coade, Co-Chair Professor David Halen, Co-Chair Professor Colleen Conway Associate Professor Max Dimoff Professor Daniel Herwitz Joachim C. Angster [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-2563-2819 © Joachim C. Angster 2020 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to members of my Doctoral Committee and to my teacher Professor Caroline Coade in particular, for making me a better musician. I also would like to give special thanks to my collaborators Arianna Dotto, Meridian Prall, Ji-Hyang Gwak, Taylor Flowers, and Nathaniel Pierce. Finally, I am grateful for the continuous support of my parents, and for the invaluable help of Anna Herklotz and Gabriele Dotto. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii ABSTRACT iv FIRST DISSERTATION RECITAL: Program 1 Program Notes 2 SECOND DISSERTATION RECITAL: Program 18 Program Notes 19 THIRD DISSERTATION RECITAL: Program 27 Program Notes 28 BIBLIOGRAPHY 40 iii ABSTRACT This dissertation pertains to three viola recitals, which were respectively performed on 2 October 2019, 20 January 2020, and 9 March 2020. Each recital program embraced a specific theme involving little-performed works as well as staples from the viola repertoire, and covered a wide range of different musical styles. The first recital, performed with violinist Arianna Dotto, focused on violin and viola duo repertoire. Two pieces in the Classical and early Romantic styles by W. A. Mozart and L. -

Xamsecly943541z Ç

Catalogo 2018 Confezione: special 2 LP BRIL 90008 Confezione: Jewel Box 1 CD BRIL 95388 Medio Prezzo Medio Prezzo Distribuzione Italiana 07/03/2017 Distribuzione Italiana 01/12/2017 Genere: Classica da camera Genere: Classica da camera Ç|xAMSECLy900087z Ç|xAMSECLy953885z JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH JOHN ADAMS Variazioni Goldberg BWV 988 Piano Music - Opere per pianoforte China Gates, Phrygian Gates, American Berserk, Hallelujah Junction PIETER-JAN BELDER cv JEROEN VAN VEEN pf "Il minimalismo, ma non come lo conoscete”, così il Guardian ha descritto la musica di John Adams. Attivo in quasi tutti i generi musicali, dall’opera alle colonne sonore, dal jazz Confezione: long box 2 LP BRIL 90007 Medio Prezzo alla musica da camera, la sua apertura e il suo stile originale ha catturato il pubblico in Distribuzione Italiana 15/12/2015 tutto il mondo, superando i confini della musica classica rigorosa. Anche nelle sue opere Genere: Classica da camera per pianoforte, il compositore statunitense utilizza un 'ampia varietà di tecniche e stili, come disponibile anche ci mostra il pioniere della musica minimalista Jeroen van Veen assecondato dalla moglie 2 CD BRIL 95129 Ç|xAMSECLy900070z Sandra van Veen al secondo pianoforte. Durata: 57:48 Confezione: Jewel Box 1 CD BRIL 94047 YANN TIERSEN Medio Prezzo Pour Amélie, Goodbye Lenin (musica per Distribuzione Italiana 01/01/2005 pianoforte) Genere: Classica Strum.Solistica Ç|xAMSECLy940472z Parte A: Pour Amélie, Parte B: Goodbye Lenin JEROEN VAN VEEN pf ISAAC ALBENIZ Opere per chitarra Confezione: long box 1 LP BRIL 90006 Alto Prezzo Distribuzione Italiana 15/12/2015 Genere: Classica Orchestrale GIUSEPPE FEOLA ch disponibile anche 1 CD BRIL 94637 Ç|xAMSECLy900063z Isaac Albeniz, assieme a de Falla e Granados, è considerato non solo uno dei più grandi compositori spagnoli, ma uno dei padri fondatori della musica moderna spagnola. -

Scherzo Noviembre 2013.Indd

REVISTA DE MÚSICA Año XXVIII - Nº 290 - Noviembre 2013 - 7 € DOSIER Benjamin Britten ENCUENTROS Jonas Dvorák a los 50 Año XXVIII - Nº 290 Noviembre 2013 Kaufmann ACTUALIDAD Alfred Brendel DISCOS Réquiem alemán de Brahms nueva revista digital y tienda online Acaba de nacer El arte de la fuga, nueva revista digital y tienda online, dedicada a cubrir el mundo de la música clásica internacional desde una perspectiva española, con colaboradores de primer nivel que ofrecen reseñas y noticias diarias. Además, y en asociación con El arte de la fuga, en breve comenzará su andadura La Quinta de Mahler, una tienda física ubicada en el centro de la ciudad de Madrid, a pocos pasos de la Puerta del Sol, el Teatro Real y la Plaza Mayor. 5 oficina & almacén: Timoteo Padrós, 31 | 28200 San Lorenzo de El Escorial | España información & pedidos: tel. (+34) 91 896 1480 | [email protected] www.elartedelafuga.com 290-Pliego 1_207-pliego 1 22/10/13 14:59 Página 1 AÑO XXVIII - Nº 290 - Noviembre 2013 - 7 € 2 OPINIÓN Introducción y allegro Juan Lucas 72 CON NOMBRE Donde habita el recuerdo PROPIO Juan Antonio Llorente 75 6 Alfred Brendel La narrativa, inspiración Christian Springer operística Santiago Martín Bermúdez 78 8 AGENDA La música audiovisual David Rodríguez Cerdán 84 14 ACTUALIDAD NACIONAL ENCUENTROS 30 ACTUALIDAD Jonas Kaufmann INTERNACIONAL Rafael Banús Irusta 88 40 ENTREVISTA EDUCACIÓN Anne-Sophie Mutter Joan-Albert Serra 92 Benjamín G. Rosado 44 Discos del mes JAZZ Pablo Sanz 93 45 SCHERZO DISCOS Sumario LA GUÍA 94 71 DOSIER CONTRAPUNTO Norman -

A Summer of Concerts Live on WFMT

A summer of concerts live on WFMT Thomas Wilkins conducts the Grant Park Music Festival from the South Shore Cultural Center Friday, July 29, 6:30 pm Air Check Dear Member, The Guide Greetings! Summer in Chicago is a time to get out and about, and both WTTW and WFMT are out in The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT the community during these warmer months. We’re bringing PBS Kids walk-around character Nature Renée Crown Public Media Center Cat outdoors to engage with kids around the city and suburbs, encouraging them to discover the 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue natural world in their own back yards; and we recently launched a new Chicago Loop app, which you Chicago, Illinois 60625 can download to join Geoffrey Baer and explore our great city and its architectural wonders like never Main Switchboard before. And on musical front, WFMT is proud to bring you live summer (773) 583-5000 concerts from the Ravinia and Grant Park festivals; this month, in a first Member and Viewer Services for the station, we will be bringing you a special Grant Park concert from (773) 509-1111 x 6 the South Shore Cultural Center with the Grant Park Orchestra led by WFMT Radio Networks (773) 279-2000 guest conductor Thomas Wilkins. Remember that you can take all of this Chicago Production Center content with you on your phone. Go to iTunes to download the WTTW/ (773) 583-5000 PBS Video app, the new WTTW Chicago’s Loop app, and the WFMT app for Apple and Android.