DRAFT- NOT for CITATION OR FURTHER CIRCULATION Rising Local Identity and Opposition to Globalization in Taiwan and Hong Kong: A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civic Party (Cp)

立法會 CB(2)1335/17-18(04)號文件 LC Paper No. CB(2)1335/17-18(04) CIVIC PARTY (CP) Submission to the United Nations UNIVERSAL PERIODIC REVIEW Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) CHINA 31st session of the UPR Working Group of the Human Rights Council November 2018 Introduction 1. We are making a stakeholder’s submission in our capacity as a political party of the pro-democracy camp in Hong Kong for the 2018 Universal Periodic Review on the People's Republic of China (PRC), and in particular, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR). Currently, our party has five members elected to the Hong Kong Legislative Council, the unicameral legislature of HKSAR. 2. In the Universal Periodic Reviews of PRC in 2009 and 2013, not much attention was paid to the human rights, political, and social developments in the HKSAR, whilst some positive comments were reported on the HKSAR situation. i We wish to highlight that there have been substantial changes to the actual implementation of human rights in Hong Kong since the last reviews, which should be pinpointed for assessment in this Universal Periodic Review. In particular, as a pro-democracy political party with members in public office at the Legislative Council (LegCo), we wish to draw the Council’s attention to issues related to the political structure, election methods and operations, and the exercise of freedom and rights within and outside the Legislative Council in HKSAR. Most notably, recent incidents demonstrate that the PRC and HKSAR authorities have not addressed recommendations made by the Human Rights Committee in previous concluding observations in assessing the implementation of International Convention on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). -

Now Is the Time to Give Civic Party Its Last Rites

8 | Wednesday, April21, 2021 HONG KONG EDITION | CHINA DAILY COMMENTHK Yang Sheng Now is the time to give Harris’ antics Civic Party its last rites threaten to bring Grenville Cross says the political group has done more harm HKBA down to Hong Kong than any other and its departure is long overdue aul Harris, a former British politician and current chair- man of the Hong Kong Bar Association (HKBA), spouted some uneducated theories that fully exposed his hypo- n November 11, 2020, the the national anthem law, both of which Hong critical self in a recent interview, in which he questioned National People’s Con- Kong was constitutionally obliged to enact. In Pthe legitimacy of the National People’s Congress’ (NPC) decision gress Standing Committee consequence, there was legislative gridlock, to improve Hong Kong’s electoral system, claiming that the vet- (NPCSC) adopted a resolu- with 14 bills and 89 items of subsidiary legisla- ting of candidates by a review committee may violate voter rights tion whereby members of tion being blocked, many a ecting people’s by limiting their choices. However, he failed to mention the fact the Hong Kong Legislative livelihoods. Although the deadlock was fi nally that vetting candidates is a common practice around the world to Council immediately lost Grenville Cross broken on May 18, no thanks to Kwok, his ensure national security or other national interests. Would Paul their seats if, in violation of their oaths of The author is a senior counsel, law professor was an unprecedented move to paralyze the Harris, who served as a councilor of Oxford city in the past, cast and criminal justice analyst, and was previ- o ce, they were deemed to have engaged in Legislative Council, and to prevent it from dis- the same human rights abuse suspicion over the relevant laws of O ously the director of public prosecutions of charging the legislative functions required of various nefarious activities. -

Fifth Legislative Council (2012-2016)

Fifth Legislative Council (2012-2016) President Hon Jasper TSANG Yok-sing, GBM, GBS, JP (Hong Kong Island+) Members Hon Albert HO Chun-yan Hon LEE Cheuk-yan (District Council - Second*) (New Territories West+) Hon James TO Kun-sun Hon CHAN Kam-lam, GBS, JP (District Council - Second*) (Kowloon East+) Hon LEUNG Yiu-chung Dr Hon LAU Wong-fat, GBM, GBS, JP (New Territories West+) (Heung Yee Kuk*) Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon TAM Yiu-chung, GBM, GBS, JP (New Territories East+) (New Territories West+) Hon Abraham SHEK Lai-him, GBS, JP Hon Tommy CHEUNG Yu-yan, GBS, JP (Real Estate and Construction*) (Catering*) Hon Frederick FUNG Kin-kee, SBS, JP Hon Vincent FANG Kang, GBS, JP (District Council - Second*) (Wholesale and Retail*) Hon WONG Kwok-hing, BBS, MH Prof Hon Joseph LEE Kok-long, SBS, JP, (Hong Kong Island+) PhD, RN (Health Services*) Hon Jeffrey LAM Kin-fung, GBS, JP Hon Andrew LEUNG Kwan-yuen, GBS, (Commercial - First*) JP (Industrial - First*) Hon WONG Ting-kwong, SBS, JP Hon Ronny TONG Ka-wah, SC (Import and Export*) (New Territories East+) (up to 30 September 2015) Hon Cyd HO Sau-lan, JP Hon Starry LEE Wai-king, SBS, JP (Hong Kong Island+) (District Council - Second*) Dr Hon LAM Tai-fai, SBS, JP Hon CHAN Hak-kan, BBS, JP (Industrial - Second*) (New Territories East+) Hon CHAN Kin-por, BBS, JP Dr Hon Priscilla LEUNG Mei-fun, SBS, (Insurance*) JP (Kowloon West+) Dr Hon LEUNG Ka-lau Hon CHEUNG Kwok-che (Medical*) (Social Welfare*) Hon WONG Kwok-kin, SBS, JP Hon IP Kwok-him, GBS, JP (Kowloon East+) (District Council - First*) Hon Mrs -

Hong Kong: in the Name of National Security Human Rights Violations Related to the Implementation of the Hong Kong National Security Law

HONG KONG: IN THE NAME OF NATIONAL SECURITY HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS RELATED TO THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE HONG KONG NATIONAL SECURITY LAW Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 10 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2021 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2021 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 17/4197/2021 June 2021 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 1. BACKGROUND 3 2. ACTS AUTHORITIES CLAIM TO BE ‘ENDANGERING NATIONAL SECURITY’ 5 EXERCISING THE RIGHT OF PEACEFUL ASSEMBLY 5 EXERCISING THE RIGHT TO FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION 7 EXERCISING THE RIGHT TO FREEDOM OF ASSOCIATION 9 ENGAGING IN INTERNATIONAL POLITICAL ADVOCACY 10 3. HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS ENABLED BY THE NSL 12 STRINGENT THRESHOLD FOR BAIL AND PROLONGED PERIOD OF PRETRIAL DETENTION 13 FREEDOM OF MOVEMENT 15 RETROACTIVITY 16 SPECIALLY APPOINTED JUDGES 16 RIGHT TO LEGAL COUNSEL 17 ADEQUATE TIME AND FACILITIES TO PREPARE A DEFENCE 17 4. -

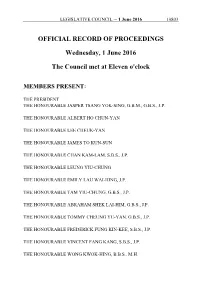

Official Record of Proceedings

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 1 June 2016 10803 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 1 June 2016 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-HING, B.B.S., M.H. 10804 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 1 June 2016 PROF THE HONOURABLE JOSEPH LEE KOK-LONG, S.B.S., J.P., Ph.D., R.N. THE HONOURABLE JEFFREY LAM KIN-FUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW LEUNG KWAN-YUEN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG TING-KWONG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CYD HO SAU-LAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE STARRY LEE WAI-KING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LAM TAI-FAI, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAK-KAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KIN-POR, B.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PRISCILLA LEUNG MEI-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LEUNG KA-LAU THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG KWOK-CHE THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-KIN, S.B.S. -

Open Dissertation FINAL2.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Communications AFTER A RAINY DAY IN HONG KONG: MEDIA, MEMORY AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS, A LOOK AT HONG KONG’S 2014 UMBRELLA MOVEMENT A Dissertation in Mass Communications by Kelly A. Chernin © 2017 Kelly A. Chernin Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2017 The dissertation of Kelly A. Chernin was reviewed and approved* by the following: Matthew F. Jordan Associate Professor of Media Studies Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee C. Michael Elavsky Associate Professor of Media Studies Michelle Rodino-Colocino Associate Professor of Media Studies Stephen H. Browne Liberal Arts Research Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Ford Risley Professor of Communications Associate Dean of the College of Communications *Signatures are on file in the graduate school. ii ABSTRACT The period following an occupied social movement is often overlooked, yet it is an important moment in time as political and economic systems are potentially vulnerable. In 2014, after Hong Kong’s Chief Executive declared that the citizens of Hong Kong would be unable to democratically elect their leader in the upcoming 2017 election, a 79-day occupation of major city centers ensued. The memory of the three-month occupation, also known as the Umbrella Movement was instrumental in shaping a political identity for Hong Kong’s residents. Understanding social movements as a process and not a singular event, an analytic mode that problematizes linear temporal constructions, can help us move beyond the deterministic and celebratory views often associated with technology’s role in social movement activism. -

Hong Kong's National Security

FEBRUARY 2021 HONG KONG’S NATIONAL SECURITY LAW: A Human Rights and Rule of Law Analysis by Lydia Wong and Thomas E. Kellogg THE NATIONAL SECURITY LAW constitutes one of the greatest threats to human rights and the rule of law in Hong Kong since the 1997 handover. This report was researched and written by Lydia Wong (alias, [email protected]), research fellow, Georgetown Center for Asian Law; and Thomas E. Kellogg ([email protected]), executive director, Georgetown Center for Asian Law, and adjunct professor of law, Georgetown University Law Center. (Ms. Wong, a scholar from the PRC, decided to use an alias due to political security concerns.) The authors would like to thank three anonymous reviewers for their comments on the draft report. We also thank Prof. James V. Feinerman for both his substantive inputs on the report, and for his longstanding leadership and guidance of the Center for Asian Law. We would also like to thank the Hong Kongers we interviewed for this report, for sharing their insights on the situation in Hong Kong. All photographs by CLOUD, a Hong Kong-based photographer. Thanks to Kelsey Harrison for administrative and publishing support. Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY i The National Security Law: Undermining the Basic Law, Threatening Human Rights iii Implementation of the NSL iv I INTRODUCTION 1 THE HONG KONG NATIONAL SECURITY LAW: II A HUMAN RIGHTS AND RULE OF LAW ANALYSIS 6 The NSL: Infringing LegCo Authority 9 New NSL Structures: A Threat to Hong Kong’s Autonomy 12 The NSL and the Courts: Judicial -

Six-Monthly Report on Hong Kong 1 July to 31 December 2016

THE SIX-MONTHLY REPORT ON HONG KONG 1 JULY TO 31 DECEMBER 2016 Deposited in Parliament by the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs 24 FEBRUARY 2017 1 Contents FOREWORD .............................................................................................................. 4 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 7 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ELECTIONS ...................................................................... 7 Confirmation Form...................................................................................................... 8 Allegations of manipulation and intimidation .............................................................. 9 Sixth Legislative Council .......................................................................................... 10 Swearing-in of legislators ......................................................................................... 10 Judicial reviews ........................................................................................................ 10 Legislative Council adjournments ............................................................................. 11 Court hearing and NPCSC interpretation of the Basic Law ...................................... 11 Outcome of judicial proceedings .............................................................................. 14 Further legal action.................................................................................................. -

“Localism” in Hong Kong a New Path for the Democracy Movement?

China Perspectives 2016/3 | 2016 China’s Policy in the China Seas The Growth of “Localism” in Hong Kong A New Path for the Democracy Movement? Ying-ho Kwong Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/7057 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.7057 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 1 September 2016 Number of pages: 63-68 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Ying-ho Kwong, « The Growth of “Localism” in Hong Kong », China Perspectives [Online], 2016/3 | 2016, Online since 01 September 2016, connection on 14 September 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/7057 © All rights reserved Current affairs China perspectives The Growth of “Localism” in Hong Kong A New Path for the Democracy Movement? YING-HO KWONG series of political protests in recent years, including localist rallies maintain harmonious relations, and supported the reversion of sovereignty for the June 4 Massacre, anti-parallel trading protests, and the Mong from Britain to China after 1997 under the principle of “One Country, Two AKok Riot, have triggered concerns over the development of “localism” Systems.” (4) In fact, Hong Kong’s democrats have always been divided by (bentu zhuyi 本土主義 ) in Hong Kong. For decades, traditional pan-demo - ideological differences, but have sought room for co-operation on political cratic parties ( fan minzhupai 泛民主派 ) have been struggling with the Chi - issues. The collaboration among democrats strengthened during and after nese government over political development. Although many of them have the Tiananmen Massacre. During the 1989 democracy movement in China, persistently bargained with the Beijing leaders, progress towards democracy Hong Kong democrats formed the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patri - remains stagnant. -

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Friday, 24 June 2016 the Council Continued to Meet at Nine O'clock

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 24 June 2016 12633 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Friday, 24 June 2016 The Council continued to meet at Nine o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-HING, B.B.S., M.H. THE HONOURABLE JEFFREY LAM KIN-FUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW LEUNG KWAN-YUEN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG TING-KWONG, S.B.S., J.P. 12634 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 24 June 2016 THE HONOURABLE CYD HO SAU-LAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE STARRY LEE WAI-KING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAK-KAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KIN-POR, B.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PRISCILLA LEUNG MEI-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG KWOK-CHE THE HONOURABLE IP KWOK-HIM, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE PAUL TSE WAI-CHUN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG KWOK-HUNG THE HONOURABLE ALBERT CHAN WAI-YIP THE HONOURABLE WONG YUK-MAN THE HONOURABLE CLAUDIA MO THE HONOURABLE MICHAEL TIEN PUK-SUN, B.B.S., J.P. -

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 5 December 2019 the Council Continued to Meet at Nine O'clock

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 5 December 2019 2853 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 5 December 2019 The Council continued to meet at Nine o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE ANDREW LEUNG KWAN-YUEN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, G.B.S., J.P. PROF THE HONOURABLE JOSEPH LEE KOK-LONG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JEFFREY LAM KIN-FUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG TING-KWONG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE STARRY LEE WAI-KING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAK-KAN, B.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KIN-POR, G.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PRISCILLA LEUNG MEI-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-KIN, S.B.S., J.P. 2854 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 5 December 2019 THE HONOURABLE MRS REGINA IP LAU SUK-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE PAUL TSE WAI-CHUN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CLAUDIA MO THE HONOURABLE STEVEN HO CHUN-YIN, B.B.S. THE HONOURABLE FRANKIE YICK CHI-MING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WU CHI-WAI, M.H. THE HONOURABLE YIU SI-WING, B.B.S. THE HONOURABLE CHARLES PETER MOK, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN CHI-CHUEN THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAN-PAN, B.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG CHE-CHEUNG, S.B.S., M.H., J.P. THE HONOURABLE KENNETH LEUNG THE HONOURABLE ALICE MAK MEI-KUEN, B.B.S., J.P. -

Minutes of the 31St Meeting Held in Conference Room 1 of the Legislative Council Complex at 2:30 Pm on Friday, 8 July 2016

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(2)1912/15-16 Ref : CB2/H/5/15 House Committee of the Legislative Council Minutes of the 31st meeting held in Conference Room 1 of the Legislative Council Complex at 2:30 pm on Friday, 8 July 2016 Members present: Hon Andrew LEUNG Kwan-yuen, GBS, JP (Chairman) Hon MA Fung-kwok, SBS, JP (Deputy Chairman) Hon Albert HO Chun-yan Hon LEE Cheuk-yan Hon James TO Kun-sun Hon CHAN Kam-lam, GBS, JP Hon LEUNG Yiu-chung Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon TAM Yiu-chung, GBM, GBS, JP Hon Abraham SHEK Lai-him, GBS, JP Hon Tommy CHEUNG Yu-yan, GBS, JP Hon Frederick FUNG Kin-kee, SBS, JP Hon Jeffrey LAM Kin-fung, GBS, JP Hon WONG Ting-kwong, SBS, JP Hon Cyd HO Sau-lan, JP Hon Starry LEE Wai-king, SBS, JP Dr Hon LAM Tai-fai, SBS, JP Hon CHAN Hak-kan, BBS, JP Hon CHAN Kin-por, BBS, JP Dr Hon Priscilla LEUNG Mei-fun, SBS, JP Dr Hon LEUNG Ka-lau Hon CHEUNG Kwok-che Hon IP Kwok-him, GBS, JP Hon Mrs Regina IP LAU Suk-yee, GBS, JP Hon Paul TSE Wai-chun, JP Hon LEUNG Kwok-hung Hon Albert CHAN Wai-yip Hon WONG Yuk-man Hon Claudia MO - 2 - Hon Michael TIEN Puk-sun, BBS, JP Hon James TIEN Pei-chun, GBS, JP Hon NG Leung-sing, SBS, JP Hon Steven HO Chun-yin, BBS Hon WU Chi-wai, MH Hon YIU Si-wing, BBS Hon Gary FAN Kwok-wai Hon CHAN Chi-chuen Hon CHAN Han-pan, JP Dr Hon Kenneth CHAN Ka-lok Hon CHAN Yuen-han, SBS, JP Hon Alice MAK Mei-kuen, BBS, JP Hon Dennis KWOK Hon Christopher CHEUNG Wah-fung, SBS, JP Dr Hon Fernando CHEUNG Chiu-hung Hon SIN Chung-kai, SBS, JP Dr Hon Helena WONG Pik-wan Hon IP Kin-yuen Dr Hon Elizabeth QUAT, JP