Investigating User Preferences for Services in Rural Areas of Scotland: a Territorial Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inner and Outer Hebrides Hiking Adventure

Dun Ara, Isle of Mull Inner and Outer Hebrides hiking adventure Visiting some great ancient and medieval sites This trip takes us along Scotland’s west coast from the Isle of 9 Mull in the south, along the western edge of highland Scotland Lewis to the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides (Western Isles), 8 STORNOWAY sometimes along the mainland coast, but more often across beautiful and fascinating islands. This is the perfect opportunity Harris to explore all that the western Highlands and Islands of Scotland have to offer: prehistoric stone circles, burial cairns, and settlements, Gaelic culture; and remarkable wildlife—all 7 amidst dramatic land- and seascapes. Most of the tour will be off the well-beaten tourist trail through 6 some of Scotland’s most magnificent scenery. We will hike on seven islands. Sculpted by the sea, these islands have long and Skye varied coastlines, with high cliffs, sea lochs or fjords, sandy and rocky bays, caves and arches - always something new to draw 5 INVERNESSyou on around the next corner. Highlights • Tobermory, Mull; • Boat trip to and walks on the Isles of Staffa, with its basalt columns, MALLAIG and Iona with a visit to Iona Abbey; 4 • The sandy beaches on the Isle of Harris; • Boat trip and hike to Loch Coruisk on Skye; • Walk to the tidal island of Oronsay; 2 • Visit to the Standing Stones of Calanish on Lewis. 10 Staffa • Butt of Lewis hike. 3 Mull 2 1 Iona OBAN Kintyre Islay GLASGOW EDINBURGH 1. Glasgow - Isle of Mull 6. Talisker distillery, Oronsay, Iona Abbey 2. -

Lionel Mission Hall, Lionel, Isle of Lewis, HS2 0XD Property

Lionel Mission Hall, Lionel, Isle of Lewis, HS2 0XD Property Detached church building located in the peaceful village of Lionel, to the north of the Isle of Lewis. With open views surrounding, the property benefits from a wonderful spot and presents a very attractive purchase opportunity and is only a short drive from the main town of Stornoway. Entrance Vestibule: 2.59m x 2.25m Main Hall: 10.85m x 6.46m Gross Internal Floor Area: 76.2 m2 Services The property is serviced by electricity only. Mains water and sewer are conveniently located nearby. Grounds The property is situated on a small plot, with grounds surrounding the church bounded by wire fencing. Planning The Church Hall is not listed, and could be used, without the necessity of obtaining change of use consent, as a Creche, day nursery, day centre, educational establishment, museum or public library. It also has potential for a variety of other uses, such as retail, commercial or community uses, subject to obtaining the appropriate consents. Conversion to residential accommodation is also possible, again subject to the usual consents. Local Area Lionel is a village on the North of the Isle of Lewis and is less than a ten-minute drive from the Butt of Lewis. The village benefits from excellent access routes around the island and is only 26 miles from Stornoway. The neighbouring villages provide a wide range of amenities including shop, filling station, school, post office, bar restaurant, laundrette and charity shop. Stornoway is the main town of the Western Isles and the capital of Lewis. -

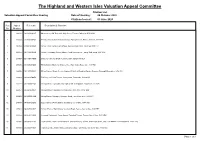

Appeal Citation List External

The Highland and Western Isles Valuation Appeal Committee Citation List Valuation Appeal Committee Hearing Date of Hearing : 06 October 2020 Citations Issued : 05 June 2020 Seq Appeal Reference Description & Situation No Number 1 269288 01/01/388013/7 Museum etc, Old Town Hall, High Street, Thurso, Caithness, KW14 8AJ 2 299360 01/05/010080/1 Primary School, Noss Primary School, Ackergill Street, Wick, Caithness, KW1 4DT 3 299359 01/05/585000/8 School, Wick Community Campus, Newton Road, Wick, Caithness, KW1 5LT 4 299358 02/11/027950/9 School, Secondary School, Manse Road, Kinlochbervie, Lairg, Sutherland, IV27 4RG 5 299357 02/13/081300/0 Distillery, Clynelish Distillery, Brora, Sutherland, KW9 6LR 6 259285 03/12/020600/4 Filling Station, Black Isle Motors, Tore, Muir of Ord, Ross-shire, IV6 7RZ 7 266056 03/21/009580/2 Filling Station, Skiach Service Station, 4D Airfield Road Ind Estate, Evanton, Dingwall, Ross-shire, IV16 9XJ 8 299363 03/23/335005/0 Distillery, Golf View Terrace, Invergordon, Ross-shire, IV18 0HW 9 259242 03/23/380240/5 Filling Station, Four Oaks, 130 High Street, Invergordon, Ross-shire, IV18 0AE 10 266057 03/32/465005/4 Filling Station, 1 Knockbreck Road, Tain, Ross-shire, IV19 1BW 11 266058 03/32/555164/0 Filling Station, Morangie, Morangie Road, Tain, Ross-shire, IV19 1PY 12 265484 04/05/032820/2 Supermarket & Filling Station, Broadford, Isle of Skye, IV49 9AB 13 299361 04/06/036250/2 School, Portree High School, Viewfield Road, Portree, Isle of Skye, IV51 9ET 14 299268 04/06/041450/8 Licensed Restaurant, Caroy House, -

2020 Cruise Directory Directory 2020 Cruise 2020 Cruise Directory M 18 C B Y 80 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−− 17 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−−

2020 MAIN Cover Artwork.qxp_Layout 1 07/03/2019 16:16 Page 1 2020 Hebridean Princess Cruise Calendar SPRING page CONTENTS March 2nd A Taste of the Lower Clyde 4 nights 22 European River Cruises on board MS Royal Crown 6th Firth of Clyde Explorer 4 nights 24 10th Historic Houses and Castles of the Clyde 7 nights 26 The Hebridean difference 3 Private charters 17 17th Inlets and Islands of Argyll 7 nights 28 24th Highland and Island Discovery 7 nights 30 Genuinely fully-inclusive cruising 4-5 Belmond Royal Scotsman 17 31st Flavours of the Hebrides 7 nights 32 Discovering more with Scottish islands A-Z 18-21 Hebridean’s exceptional crew 6-7 April 7th Easter Explorer 7 nights 34 Cruise itineraries 22-97 Life on board 8-9 14th Springtime Surprise 7 nights 36 Cabins 98-107 21st Idyllic Outer Isles 7 nights 38 Dining and cuisine 10-11 28th Footloose through the Inner Sound 7 nights 40 Smooth start to your cruise 108-109 2020 Cruise DireCTOrY Going ashore 12-13 On board A-Z 111 May 5th Glorious Gardens of the West Coast 7 nights 42 Themed cruises 14 12th Western Isles Panorama 7 nights 44 Highlands and islands of scotland What you need to know 112 Enriching guest speakers 15 19th St Kilda and the Outer Isles 7 nights 46 Orkney, Northern ireland, isle of Man and Norway Cabin facilities 113 26th Western Isles Wildlife 7 nights 48 Knowledgeable guides 15 Deck plans 114 SuMMER Partnerships 16 June 2nd St Kilda & Scotland’s Remote Archipelagos 7 nights 50 9th Heart of the Hebrides 7 nights 52 16th Footloose to the Outer Isles 7 nights 54 HEBRIDEAN -

Water Safety Policy in Scotland —A Guide

Water Safety Policy in Scotland —A Guide 2 Introduction Scotland is surrounded by coastal water – the North Sea, the Irish Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. In addition, there are also numerous bodies of inland water including rivers, burns and about 25,000 lochs. Being safe around water should therefore be a key priority. However, the management of water safety is a major concern for Scotland. Recent research has found a mixed picture of water safety in Scotland with little uniformity or consistency across the country.1 In response to this research, it was suggested that a framework for a water safety policy be made available to local authorities. The Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA) has therefore created this document to assist in the management of water safety. In order to support this document, RoSPA consulted with a number of UK local authorities and organisations to discuss policy and water safety management. Each council was asked questions around their own area’s priorities, objectives and policies. Any policy specific to water safety was then examined and analysed in order to help create a framework based on current practice. It is anticipated that this framework can be localised to each local authority in Scotland which will help provide a strategic and consistent national approach which takes account of geographical areas and issues. Water Safety Policy in Scotland— A Guide 3 Section A: The Problem Table 1: Overall Fatalities 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 2010 2011 2012 2013 Data from National Water Safety Forum, WAID database, July 14 In recent years the number of drownings in Scotland has remained generally constant. -

The Gretna Bombing – 7Th April 1941

Acknowledgements This booklet has been made possible by generous funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund, The Armed Forces Community Covenant and Dumfries and Galloway Council, who have all kindly given The Devil’s Porridge Museum the opportunity to share the fascinating story of heroic Border people. Special thanks are given to all those local people who participated in interviews which helped to gather invaluable personal insights and key local knowledge. A special mention is deserved for the trustees and volunteers of the Devil’s Porridge Museum, who had the vision and drive to pursue the Solway Military Coast Project to a successful conclusion. Many thanks also to the staff from local libraries and archives for their assistance and giving access to fascinating sources of information. Written and Researched by Sarah Harper Edited by Richard Brodie ©Eastriggs and Gretna Heritage Group (SCIO) 2018 1 th The Gretna Bombing – 7 April 1941 The township of Gretna was built during the First World War to house many of the workers who produced cordite at the ‘greatest munitions factory on Earth’ which straddled the Scottish-English border. You might be forgiven if you had thought that Gretna and its twin township of Eastriggs would be constructed on a functional basis with little attention to detail. This was the case in the early days when a huge timber town was built on a grid system for the labourers and tradesmen, but, so intent was the Government on retaining the vital workforce, that it brought in the best town planners and architects to provide pleasant accommodation. -

Scottish Sanitary Survey Report

Scottish Sanitary Survey Report Sanitary Survey Report Loch Roag: Barraglom LH-185-120-08 September 2013 Loch Roag: Barraglom Sanitary Report Title Survey Report Project Name Scottish Sanitary Survey Food Standards Agency Client/Customer Scotland Cefas Project Reference C5792C Document Number C5792C_2013_8 Revision Final V1.0 Date 6/1/2014 Revision History Revision Date Pages revised Reason for revision number 0.1 30/9/2013 All External draft Correction of typographical 1.0 6/1/2014 14,19 errors/omissions identified during consultation Name Position Date Michelle Price-Hayward, Liefy Senior Shellfish Hygiene Authors Hendrikz, Jessica Larkham, 6/1/2014 Scientist Frank Cox Principal Shellfish Hygiene Checked Ron Lee 6/1/2014 Scientist Principal Shellfish Hygiene Approved Ron Lee 6/1/2014 Scientist This report was produced by Cefas for its Customer, FSAS, for the specific purpose of providing a sanitary survey as per the Customer’s requirements. Although every effort has been made to ensure the information contained herein is as complete as possible, there may be additional information that was either not available or not discovered during the survey. Cefas accepts no liability for any costs, liabilities or losses arising as a result of the use of or reliance upon the contents of this report by any person other than its Customer. Centre for Environment, Fisheries & Aquaculture Science, Weymouth Laboratory, Barrack Road, The Nothe, Weymouth DT4 8UB. Tel 01305 206 600 www.cefas.defra.gov.uk Loch Roag Barraglom Sanitary Survey Report V1.0 6/1/2014 i Report Distribution – Loch Roag: Barraglom Date Name Agency Joyce Carr Scottish Government David Denoon SEPA Hazel MacLeod SEPA Fiona Garner Scottish Water Alex Adrian Crown Estate Colm Fraser Comhairle nan Eilean Siar Paul Tyler HMMH (Scotland) Ltd Cree McKenzie Harvester Partner Organisation The hydrographic assessment and the shoreline survey and its associated report were undertaken by SRSL, Oban. -

Scotland's First Settlers

prev home next print SCOTLAND’S FIRST SETTLERS SECTION 9 9 Retrospective Discussion | Karen Hardy & Caroline Wickham-Jones The archive version of the text can be obtained from the project archive on the Archaeology Data Service (ADS) website, after agreeing to their terms and conditions: ads.ahds.ac.uk/catalogue/resources.html?sfs_ba_2007 > Downloads > Documents > Final Reports. From here you can download the file ‘W-J,_SFS_Final_discussion.pdf’. 9.1 Introduction Scotland’s First Settlers (SFS) was set up to look for evidence of the earliest foragers, or Mesolithic, settlement around the Inner Sound, western Scotland. Particular foci of interest included the existence and nature of midden sites, the use of rockshelters and caves, and the different types of lithic raw material (including especially baked mudstone) in use. In order to implement the project a programme of survey and test pitting, together with limited excavation was set up (see Illustration 568, right). Along the way information on other sites, both Prehistoric and later was collected, and this has also been covered in this report. In Illus 568: SFS survey work in addition, a considerable amount of information on the progress. Much of the work changing nature of the landscape and environment has had to be carried out by boat been presented. Fieldwork has finished, data has been analysed. There will always be scope for further work (and this will be discussed later), but the first stages of the project have definitely come to a close. How well has it achieved its aims? 9.2 The major achievements of the project 9.2.1 Fieldwork SFS fieldwork was conducted over a period of five years between 1999 and 2004. -

Towards a Greener Applecross

Towards March 20 a Greener 2014 Applecross Developed by: Michelle Akute Derina Paramitasari Waliullah Bhuiyan Emmanuel Nii Ankrah Alejandra Claure Tripti Prajapati Paul Boateng Darge Adenew Kristine Lim María Mercedes Vanegas Shadman Shukry Kayvan Maysami Supervisors Prof.Dr.Bernd Möller Dipl.Ing.Wulf Boie, Dipl.Soz. Dorsi Germann Towards a Greener Applecross ACKNOWLEDGEMENT We would like to express our gratitude to all individuals and organizations that have assisted us throughout the course of this study. This research wouldn’t have been possible without the support of the Applecross Estate Trust, the Applecross Community Company and the Applecross Energy Efficiency program. Our special thanks goes to Allison Macleod, Valerie Hodkingson, Alasdair Macleod, Gordon Cameron, Donald Ferguson, Barry Marsh, Alistair Brown, Ian Gillies, Archie Maclellan, David Newmanand their families for their unconditional support. We would also like to express our sincere appreciation to all residents of Applecross for the warm welcome we received. We loved learning about your culture and traditional Scottish dances. Our special thanks to all the people who participated in the interviews for making time to answer our questionnaires. The research team is very grateful to our supervisors from the University of Flensburg, Prof.Dr.Bernd Möller, Dipl.Ing.Wulf Boie, Dipl.Soz. DorsiGermann for their moral support, academic guidance, and the hours spent proof-reading and reviewing the present document. Our particular appreciation to the DeutscherAkademischerAustauschDienst (DAAD, German Academic Exchange Service) and the Global Electricity Partnership for their financial support without which this experience of the International Class 2014 would not have been possible. Towards a Greener Applecross Disclaimer Although the contents were reviewed several times before being part of this report, the accuracy of the results cannot be guaranteed. -

Free Church Lochcarron & Applecross

AN CARRANNACH The General Interest Magazine of Lochcarron, Shieldaig, Applecross, Kishorn and Torridon & Kinlochewe Districts NO: 351 MARCH 2017 £1.00 Our AGM was held on the 13th January and saw some changes to the committee. George Hendry is staying on as Chieftain, Henry Dalgety is also staying on as Club President with Anne MacCuish as Vice President. Janet Price is continuing to be our Secretary. Neil Ross from Kishorn has taken on the role of Treasurer from Fionnuala Stark. Fionnuala will continue as a committee member after a number of years being Treasurer. Fiona McLeod is staying on as Publicity Officer, completing articles and updating Facebook. Andrew Slaughter is going to continue as Team Manager on his own. We thank Alan Mackay for his joint management team last season with Andrew. Bob Munro will continue as Team Coach and our Youth Coaches will be Laura Mackay and Douglas Mackenzie. Further committee members are: Liam Arnott, Lachlan Dean Morrice, Crisdean Finlayson, Peter Mackenzie, Katrine Fogt, David MacCuish and Fionnuala Stark. We would also like to thank Helen Stewart who has stepped down from the committee this year after a number of years loyal service. On the 11th February, we had our first preseason friendly against Skye 2nds. It was a beautiful day for our first game at The Battery Park. Skye started strongly and kept the Lochcarron defence busy for the opening thirty minutes going 3-nil up. Lochcarron got back into the game, just before half time, through a well worked free hit which was finished well with Crisdean Finlayson finding the back of the Skye net. -

The Battle for Roineabhal

The Battle for Roineabhal Reflections on the successful campaign to prevent a superquarry at Lingerabay, Isle of Harris, and lessons for the Scottish planning system © Chris Tyler The Battle for Roineabhal: Reflections on the successful campaign to prevent a superquarry at Lingerabay, Isle of Harris and lessons for the Scottish planning system Researched and written by Michael Scott OBE and Dr Sarah Johnson on behalf of the LINK Quarry Group, led by Friends of the Earth Scotland, Ramblers’ Association Scotland, RSPB Scotland, and rural Scotland © Scottish Environment LINK Published by Scottish Environment LINK, February 2006 Further copies available at £25 (including p&p) from: Scottish Environment LINK, 2 Grosvenor House, Shore Road, PERTH PH2 7EQ, UK Tel 00 44 (0)1738 630804 Available as a PDF from www.scotlink.org Acknowledgements: Chris Tyler, of Arnisort in Skye for the cartoon series Hugh Womersley, Glasgow, for photos of Sound of Harris & Roineabhal Pat and Angus Macdonald for cover view (aerial) of Roineabhal Turnbull Jeffrey Partnership for photomontage of proposed superquarry Alastair McIntosh for most other photos (some of which are courtesy of Lafarge Aggregates) LINK is a Scottish charity under Scottish Charity No SC000296 and a Scottish Company limited by guarantee and without a share capital under Company No SC250899 The Battle for Roineabhal Page 2 of 144 Contents 1. Introduction 2. Lingerabay Facts & Figures: An Overview 3. The Stone Age – Superquarry Prehistory 4. Landscape Quality Guardians – the advent of the LQG 5. Views from Harris – Work versus Wilderness 6. 83 Days of Advocacy – the LQG takes Counsel 7. 83 Days of Advocacy – Voices from Harris 8. -

The Porridge Grand Tour of Scotland

PEERIE SHOP CAFÉ Shetland 24 ISLAND LARDER 23 Shetland THE PORRIDGE GRAND TOUR OF SCOTLAND KIRKWALL HOTEL SCOTLAND Orkney MACKAY’S HOTEL 13 Highlands GLENGOLLY B&B Highlands FOODSTORY CAFÉ Aberdeen LOCH NESS INN 14 12 Highlands SAND DOLLAR CAFÉ THREE CHIMNEYS Aberdeen Highlands BONOBO CAFÉ BALLINTAGGART Aberdeen FARM Perthshire 15 BRIDGEVIEW STATION THE WHITEHOUSE RESTAURANT RESTAURANT 11 Dundee & Angus Argyll & Bute 21 20 PORTERS BAR & 22 NINTH WAVE RESTAURANT RESTAURANT Dundee & Angus Argyll & Bute 19 4 MONACHYLE MHOR 18 10 9 TANNOCHBRAE TEA HOTEL ROOMS Stirlingshire 5 8 Fife 17 16 IT ALL STARTED HERE 2 Glasgow THE EDINBURGH 3 1 LARDER Edinburgh EUSEBI DELI 6 Glasgow CONTINI ON GEORGE STREET FIORLIN B&B Edinburgh Scottish Borders RESTAURANT MARK SELKIRK ARMS HOTEL 7 GREENAWAY Dumfries & Galloway Edinburgh THE ITINERARIES EDINBURGH TO PERTHSHIRE AND STIRLINGSHIRE DAY ONE When you arrive at Edinburgh via the Caledonian Sleeper, start the day o with a warming bowl of porridge with fresh apricots, bananas and toasted pecans and sunflower seeds at Contini on George Street 1 (available from 8am weekdays; 10am weekends). From there, why not take a walk up the Mound in Edinburgh to explore the Museum on the Mound and Edinburgh’s historic Royal Mile to work up your appetite for lunch. What’s on the menu? Porridge of course! Head to Blackfriar’s Street and the Edinburgh Larder 22 which has on oer slow cooked meat (beef or lamb) with seasonal vegetables and skirlie (an alternative to stuing which includes oatmeal). By now you’ll be itching for a bit of history so enjoy an underground history or ghost tour with Mercat Tours.