Modeling the Survival of Athenian Owl Tetradrachms Struck in the Period from 561-42 BC from Then to the Present

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T C K a P R (E F C Bc): C P R

ELECTRUM * Vol. 23 (2016): 25–49 doi: 10.4467/20800909EL.16.002.5821 www.ejournals.eu/electrum T C K A P R (E F C BC): C P R S1 Christian Körner Universität Bern For Andreas Mehl, with deep gratitude Abstract: At the end of the eighth century, Cyprus came under Assyrian control. For the follow- ing four centuries, the Cypriot monarchs were confronted with the power of the Near Eastern empires. This essay focuses on the relations between the Cypriot kings and the Near Eastern Great Kings from the eighth to the fourth century BC. To understand these relations, two theoretical concepts are applied: the centre-periphery model and the concept of suzerainty. From the central perspective of the Assyrian and Persian empires, Cyprus was situated on the western periphery. Therefore, the local governing traditions were respected by the Assyrian and Persian masters, as long as the petty kings fulfi lled their duties by paying tributes and providing military support when requested to do so. The personal relationship between the Cypriot kings and their masters can best be described as one of suzerainty, where the rulers submitted to a superior ruler, but still retained some autonomy. This relationship was far from being stable, which could lead to manifold mis- understandings between centre and periphery. In this essay, the ways in which suzerainty worked are discussed using several examples of the relations between Cypriot kings and their masters. Key words: Assyria, Persia, Cyprus, Cypriot kings. At the end of the fourth century BC, all the Cypriot kingdoms vanished during the wars of Alexander’s successors Ptolemy and Antigonus, who struggled for control of the is- land. -

Marina Gavryushkina UC Berkeley Art History 2013

UC Berkeley Berkeley Undergraduate Journal of Classics Title The Persian Alexander: The Numismatic Portraiture of the Pontic Dynasty Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7xh6g8nn Journal Berkeley Undergraduate Journal of Classics, 2(1) ISSN 2373-7115 Author Gavryushkina, Marina Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Gavryushkina 1 The Persian Alexander: The Numismatic Portraiture of the Pontic Dynasty Marina Gavryushkina UC Berkeley Art History 2013 Abstract: Hellenistic coinage is a popular topic in art historical research as it is an invaluable resource of information about the political relationship between Greek rulers and their subjects. However, most scholars have focused on the wealthier and more famous dynasties of the Ptolemies and the Seleucids. Thus, there have been considerably fewer studies done on the artistic styles of the coins of the smaller outlying Hellenistic kingdoms. This paper analyzes the numismatic portraiture of the kings of Pontus, a peripheral kingdom located in northern Anatolia along the shores of the Black Sea. In order to evaluate the degree of similarity or difference in the Pontic kings’ modes of representation in relation to the traditional royal Hellenistic style, their coinage is compared to the numismatic depictions of Alexander the Great of Macedon. A careful art historical analysis reveals that Pontic portrait styles correlate with the individual political motivations and historical circumstances of each king. Pontic rulers actively choose to diverge from or emulate the royal Hellenistic portrait style with the intention of either gaining support from their Anatolian and Persian subjects or being accepted as legitimate Greek sovereigns within the context of international politics. -

Female Property Ownership and Status in Classical and Hellenistic Sparta

Female Property Ownership and Status in Classical and Hellenistic Sparta Stephen Hodkinson University of Manchester 1. Introduction The image of the liberated Spartiate woman, exempt from (at least some of) the social and behavioral controls which circumscribed the lives of her counterparts in other Greek poleis, has excited or horrified the imagination of commentators both ancient and modern.1 This image of liberation has sometimes carried with it the idea that women in Sparta exercised an unaccustomed influence over both domestic and political affairs.2 The source of that influence is ascribed by certain ancient writers, such as Euripides (Andromache 147-53, 211) and Aristotle (Politics 1269b12-1270a34), to female control over significant amounts of property. The male-centered perspectives of ancient writers, along with the well-known phenomenon of the “Spartan mirage” (the compound of distorted reality and sheer imaginative fiction regarding the character of Spartan society which is reflected in our overwhelmingly non-Spartan sources) mean that we must treat ancient images of women with caution. Nevertheless, ancient perceptions of their position as significant holders of property have been affirmed in recent modern studies.3 The issue at the heart of my paper is to what extent female property-holding really did translate into enhanced status and influence. In Sections 2-4 of this paper I shall approach this question from three main angles. What was the status of female possession of property, and what power did women have directly to manage and make use of their property? What impact did actual or potential ownership of property by Spartiate women have upon their status and influence? And what role did female property-ownership and status, as a collective phenomenon, play within the crisis of Spartiate society? First, however, in view of the inter-disciplinary audience of this volume, it is necessary to a give a brief outline of the historical context of my discussion. -

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

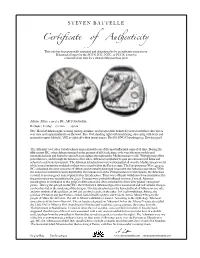

Ceificate of Auenticity

S T E V E N B A T T E L L E Ce!ificate of Au"enticity This coin has been personally inspected and determined to be an authentic ancient coin . If deemed a forgery by the ACCS, IGC, NGC, or PCGS, it may be returned at any time for a refund of the purchase price. Athens, Attica, 449-404 BC, AR Tetradrachm B076961 / U02697 17.1 Gm 25 mm Obv: Head of Athena right, wearing earring, necklace, and crested Attic helmet decorated with three olive leaves over visor and a spiral palmette on the bowl. Rev: Owl standing right with head facing, olive sprig with berry and crescent in upper left field, AOE to right; all within incuse square. Kroll 8; SNG Copenhagen 31; Dewing 1591-8 The Athenian “owl” silver tetradrachm is unquestionably one of the most influential coins of all time. During the fifth century BC, when Athens emerged as the greatest of all Greek cities, owls were the most widely used international coin and helped to spread Greek culture throughout the Mediterranean world. With the help of her powerful navy, and through the taxation of her allies, Athens accomplished to gain pre-eminance in Hellas and achieved a celebrated prosperity. The Athenian tetradrachms were well-accepted all over the Mediterranean world, while several imitations modeled on them were issued within the Persian state. The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) exhausted the silver resources of Athens and eventually destroyed irreparably the Athenian supremacy. With the mines lost and their treasury depleted by the ruinous cost of the Pelloponesian war with Sparta, the Athenians resorted to an emergency issue of plated silver tetradrachms. -

On the Date of the Trial of Anaxagoras

The Classical Quarterly http://journals.cambridge.org/CAQ Additional services for The Classical Quarterly: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here On the Date of the Trial of Anaxagoras A. E. Taylor The Classical Quarterly / Volume 11 / Issue 02 / April 1917, pp 81 - 87 DOI: 10.1017/S0009838800013094, Published online: 11 February 2009 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0009838800013094 How to cite this article: A. E. Taylor (1917). On the Date of the Trial of Anaxagoras. The Classical Quarterly, 11, pp 81-87 doi:10.1017/S0009838800013094 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/CAQ, IP address: 128.122.253.212 on 28 Apr 2015 ON THE DATE OF THE TRIAL OF ANAXAGORAS. IT is a point of some interest to the historian of the social and intellectual development of Athens to determine, if possible, the exact dates between which the philosopher Anaxagoras made that city his home. As everyone knows, the tradition of the third and later centuries was not uniform. The dates from which the Alexandrian chronologists had to arrive at their results may be conveniently summed up under three headings, (a) date of Anaxagoras' arrival at Athens, (6) date of his prosecution and escape to Lampsacus, (c) length of his residence at Athens, (a) The received account (Diogenes Laertius ii. 7),1 was that Anaxagoras was twenty years old at the date of the invasion of Xerxes and lived to be seventy-two. This was apparently why Apollodorus (ib.) placed his birth in Olympiad 70 and his death in Ol. -

Ancient Cyprus: Island of Conflict?

Ancient Cyprus: Island of Conflict? Maria Natasha Ioannou Thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy Discipline of Classics School of Humanities The University of Adelaide December 2012 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................ III Declaration........................................................................................................... IV Acknowledgements ............................................................................................. V Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 1. Overview .......................................................................................................... 1 2. Background and Context ................................................................................. 1 3. Thesis Aims ..................................................................................................... 3 4. Thesis Summary .............................................................................................. 4 5. Literature Review ............................................................................................. 6 Chapter 1: Cyprus Considered .......................................................................... 14 1.1 Cyprus’ Internal Dynamics ........................................................................... 15 1.2 Cyprus, Phoenicia and Egypt ..................................................................... -

Use This Knowledge Organizer to Become an Expert in Our Topic!

490 – 449 BC Wars with Persia ancient – from the distant past modern- belonging to the present or recent times Battle of Marathon: famous Greek victory in war civilisation – a society or culture at a particular time in history 490BC with the Persians. Pheidippides is said to have philosophy – a study of the nature of knowledge and existence run from Athens to Sparta to fetch help. citizens – a person belonging to a particular city or country Battle of Thermopylae: King Leoidas and the 480BC democracy – government of a country by representatives elected by all of the people Spartans were defeated by the Persians. archaeology - the study of ancient civilizations by digging for the remains of their buildings, Battle of Salamis – a sea battle in which the tools etc. 480BC Greeks defeated the Persians under King myth – a story told to explain a natural or social phenomenon Xerxes by sinking 200 ships. legend – a traditional story sometimes thought to be historical 480 BC – 280 BC Classical Greece hoplite – foot soldier victory – a success won against an enemy in battle Peloponnesian War between Athens & Sparta. cavalry – soldiers on horseback Sparta won. The threat of invasion by a foreign 431 - 404 BC archers - soldiers fighting with bows and arrows enemy made the Greeks fight together. Their main enemy was Persia. crest – a design representing a family or organization oath – a solemn promise to do something debate - a formal discussion or argument worn by women himation – cloak ostracon – a broken piece of pottery used to write the names -

Athens' Domain

Athens’ Domain: The Loss of Naval Supremacy and an Empire Keegan Laycock Acknowledgements This paper has a lot to owe to the support of Dr. John Walsh. Without his encouragement, guid- ance, and urging to come on a theoretically educational trip to Greece, this paper would be vastly diminished in quality, and perhaps even in existence. I am grateful for the opportunity I have had to present it and the insight I have gained from the process. Special thanks to the editors and or- ganizers of Canta/ἄειδε for their own patience and persistence. %1 For the Athenians, the sea has been a key component of culture, economics, and especial- ly warfare. The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) displayed how control of the waves was vital for victory. This was not wholly apparent at the start of the conflict. The Peloponnesian League was militarily led by Sparta who was the greatest land power in Greece; to them naval warfare was excessive. Athens, as the head of the Delian League, was the greatest sea power in Greece whose strengths lay in their navy. However, through a combination of factors, Athens lost control of the sea and lost the war despite being the superior naval power at the war’s outset. Ultimately, Athens lost because they were unable to maintain strong naval authority. The geographic position of Athens and many of its key resources ensured land-based threats made them vulnerable de- spite their naval advantage. Athens also failed to exploit their naval supremacy as they focused on land-based wars in Sicily while the Peloponnesian League built up a rivaling navy of its own. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean Culture

ANTONIJE SHKOKLJEV SLAVE NIKOLOVSKI - KATIN PREHISTORY CENTRAL BALKANS CRADLE OF AEGEAN CULTURE Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture By Antonije Shkokljev Slave Nikolovski – Katin Translated from Macedonian to English and edited By Risto Stefov Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2013 by Antonije Shkokljev, Slave Nikolovski – Katin & Risto Stefov e-book edition 2 Index Index........................................................................................................3 COMMON HISTORY AND FUTURE ..................................................5 I - GEOGRAPHICAL CONFIGURATION OF THE BALKANS.........8 II - ARCHAEOLOGICAL DISCOVERIES .........................................10 III - EPISTEMOLOGY OF THE PANNONIAN ONOMASTICS.......11 IV - DEVELOPMENT OF PALEOGRAPHY IN THE BALKANS....33 V – THRACE ........................................................................................37 VI – PREHISTORIC MACEDONIA....................................................41 VII - THESSALY - PREHISTORIC AEOLIA.....................................62 VIII – EPIRUS – PELASGIAN TESPROTIA......................................69 -

The Court of Cyrus the Younger in Anatolia: Some Remarks

STUDIES IN ANCIENT ART AND CIVILIZATION, VOL. 23 (2019) pp. 95-111, https://doi.org/10.12797/SAAC.23.2019.23.05 Michał Podrazik University of Rzeszów THE COURT OF CYRUS THE YOUNGER IN ANATOLIA: SOME REMARKS Abstract: Cyrus the Younger (born in 424/423 BC, died in 401 BC), son of the Great King Darius II (424/423-404 BC) and Queen Parysatis, is well known from his activity in Anatolia. In 408 BC he took power there as a karanos (Old Persian *kārana-, Greek κάρανος), a governor of high rank with extensive military and political competence reporting directly to the Great King. Holding his power in Anatolia, Cyrus had his own court there, in many respects modeled after the Great King’s court. The aim of this article is to show some aspects of functioning and organization of Cyrus the Younger’s court in Anatolia. Keywords: Cyrus the Younger; court; court’s staff and protocol In 4081, Cyrus, commonly known as the Younger (424/423-401), son of the Great King Darius II (424/423-404), was appointed by his father to rule over an important part of the Achaemenid Empire, Anatolia. Cyrus wielded his power there as karanos (Old Persian *kārana-, Greek κάρανος), a high- ranking governor with extensive military and political competence, reporting directly to the Great King (see Podrazik 2018, 69-83; cf. Barkworth 1993, 150-151; Debord 1999, 122-123; Briant 2002, 19, 321, 340, 600, 625-626, 878, 1002; Hyland 2013, 2-5). Cyrus held his own court while in Anatolia. The court was organized along the lines of the King’s court, but was certainly no match for it 1 All dates in the article pertain to the events before the birth of Christ except where otherwise stated.