Reading an Immigrant Community Through Their Cookbooks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where the Flavours of the World Meet: Malabar As a Culinary Hotspot

UGC Approval No:40934 CASS-ISSN:2581-6403 Where The Flavours of The World Meet: CASS Malabar As A Culinary Hotspot Asha Mary Abraham Research Scholar, Department of English, University of Calicut, Kerala. Address for Correspondence: [email protected] ABSTRACT The pre-colonial Malabar was an all-encompassing geographical area that covered the entire south Indian coast sprawling between the Western Ghats and Arabian Sea, with its capital at Kozhikkode. When India was linguistically divided and Kerala was formed in 1956, the Malabar district was geographically divided further for easy administration. The modern day Malabar, comprises of Kozhikkode, Malappuram and few taluks of Kasarkod, Kannur, Wayanad, Palakkad and Thrissur. The Malappuram and Kozhikkod region is predominantly inhabited by Muslims, colloquially called as the Mappilas. The term 'Malabar' is said to have etymologically derived from the Malayalam word 'Malavaram', denoting the location by the side of the hill. The cuisine of Malabar, which is generally believed to be authentic, is in fact, a product of history and a blend of cuisines from all over the world. Delicacies from all over the world blended with the authentic recipes of Malabar, customizing itself to the local and seasonal availability of raw materials in the Malabar Coast. As an outcome of the age old maritime relations with the other countries, the influence of colonization, spice- hunting voyages and the demands of the western administrators, the cuisine of Malabar is an amalgam of Mughal (Persian), Arab, Portuguese,, British, Dutch and French cuisines. Biriyani, the most popular Malabar recipe is the product of the Arab influence. -

In My Iraqi Kitchen: Recipes, History and Culture, Nawal Nasrallah

www.iraqi -datepalms.net 2012 In my Iraqi Kitchen: Recipes, History and Culture, Nawal Nasrallah This is a blog about the Iraqi cuisine across the centuries, from Mesopotamian times, through medieval, and to the present, by Nawal Nasrallah, author of Delights from the Garden of Eden: A Cookbook and a History of the Iraqi Cuisine (2003),winner of the Gourmand World Cookbook Awards 2007. A new revised edition is coming out soon (by Equinox Publishing), with more than 300 splendid food-related images of dishes, art, history, culture, and much more. A feast to the eyes, soul, mind, and body . MADGOOGA : AN IRAQI DATE CONFECTION SATURDAY, AUGUST 11, 2012 (USA) The date palm is the national tree of Iraq, and that is for a good reason: it was there on the land of ancient Mesopotamia that this tree was first cultivated and flourished about seven thousand years ago. From there this beautiful and generous tree spread to the rest of the Middle East. It nourished and protected the poor, enriched the fine pastries of the rich, and inspired the people’s spiritual and religious rites. Every single part of the tree, fruit and all, was used. An ancient Babylonian hymn singing its praises, tells of the 360 uses of the date palm. It was that perfect! But the date is of course the most important part of the tree, and in the Islamic Arab lore, it is a privileged food. The Prophet himself recommended having seven dates a day, as this was believed to guard against poison and witchcraft all day long. -

Saddam Hussein’S Sunni Regime Systematically Represses the Shia

Info4Migrants Iraq Profile 2 AREA 437 072 km Population 36,004 million GDP per capita $6900 CURRENCY Iraki Dinar (IQD) Languages: ARABIC and KURDISH MAIN INFORMATION “Iraq - Location Map (2013) - IRQ - UNOCHA” by OCHA. Licensed under CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons - http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ File:Iraq_-_Location_Map_(2013)_-_IRQ_-_UNO- CHA.svg#mediaviewer/File:Iraq_-_Location_Map_ (2013)_-_IRQ_-_UNOCHA.svg Official Name: Republic of Iraq (Al-Jumhuriya al-Iraqi-ya). Location: Iraq is located in the Middle East, in the most northern part of the Persian Gulf, North of Saudi Arabia, West of Iran, East of Syria and South of Turkey. Capital: Baghdad Flag Climate: Mainly hot arid climate, mild cool winters, dry, hot summers with no clouds; heavy snowfalls are typical for the northern mountainous regions, located east from Syria and South of Turkey. Ethnic composition: Arab 75 – 80%, Kurdish 15 - 20%; Assyrians, Turkmen and others 5% Religion: Muslim 97%, Christian and others 3%, (Christian 0.8%, Hindu <1%, Buddhist <1%, Jewish <1%) Coat of Arms “Coat of arms (emblem) of Iraq 2008” by File:Coat_of_arms_of_Iraq.svg was by User:Tonyjeff, based on national symbol, with the help of User:Omar86, User:Kaf- ka1 and User:AnonMoos; further modifications by AnonMoos. Arabic script modified by User:Militaryace. - symbol adopted in July 2nd, 1965, with updates. Based 3 on File:Coat_of_arms_(emblem)_of_Iraq_2004-2007.svg with stars removed and text enlarged.. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons - http:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Coat_of_arms_(emblem)_of_Iraq_2008.svg#mediaviewer/File:Coat_of_arms_(emblem)_of_Iraq_2008.svg FACTS ABOUT IRAQ Flag The Iraqi flag consists of three horizontal look-alike stripes in red, white and black with three green pentagrams, positioned on the white field. -

Iraqi Fried Chicken

Enemy Kitchen Iraqi Fried Chicken After eight weekly sessions learning how to cook Iraqi food, the students at the Hudson Guild Community Center in New York City proposed they teach me something about their families’ recipes since they now knew so much about mine. Hyasheem asked, “Do Iraqis make Southern fried chicken?” I answered that no, to my knowledge there was nothing like it in Iraqi cuisine. “Well, then let’s invent it,” he said. Hyasheem led the way and we cooked the chicken according to his specifications. 2 pounds chicken wings (or parts of your choice) 2 pounds chicken legs (or parts of your choice) 3 cups flour 6 eggs 1 tablespoon salt 2 cups breadcrumbs ½ tablespoon sumac 2-3 tablespoons Iraqi bharat spice mix (cumin, dried limes, turmeric, ginger, chili, curry, cloves, cardamom, dried rose petals, allspice) 1 tablespoon Iraqi date syrup 1 bottle sesame oil Break eggs into a bowl and beat the eggs to even consistency. In a plastic bag, mix the flour, salt, spices, date syrup and breadcrumbs. Dip a piece of chicken in the egg batter and place in the plastic bag. Repeat until about six pieces of chicken are in the bag. Close bag tightly and shake vigorously, so that the mixture of flour and spices covers each piece. In a deep pan, pour enough olive oil so that it is about 1/4 of an inch deep. Place on oven burner and let heat for 2 minutes. Place the six pieces of chicken in the pan and fry, turning often, until each side is medium-brown. -

Middle Eastern Cuisine

MIDDLE EASTERN CUISINE The term Middle Eastern cuisine refers to the various cuisines of the Middle East. Despite their similarities, there are considerable differences in climate and culture, so that the term is not particularly useful. Commonly used ingredients include pitas, honey, sesame seeds, sumac, chickpeas, mint and parsley. The Middle Eastern cuisines include: Arab cuisine Armenian cuisine Cuisine of Azerbaijan Assyrian cuisine Cypriot cuisine Egyptian cuisine Israeli cuisine Iraqi cuisine Iranian (Persian) cuisine Lebanese cuisine Palestinian cuisine Somali cuisine Syrian cuisine Turkish cuisine Yemeni cuisine ARAB CUISINE Arab cuisine is defined as the various regional cuisines spanning the Arab World from Iraq to Morocco to Somalia to Yemen, and incorporating Levantine, Egyptian and others. It has also been influenced to a degree by the cuisines of Turkey, Pakistan, Iran, India, the Berbers and other cultures of the peoples of the region before the cultural Arabization brought by genealogical Arabians during the Arabian Muslim conquests. HISTORY Originally, the Arabs of the Arabian Peninsula relied heavily on a diet of dates, wheat, barley, rice and meat, with little variety, with a heavy emphasis on yogurt products, such as labneh (yoghurt without butterfat). As the indigenous Semitic people of the peninsula wandered, so did their tastes and favored ingredients. There is a strong emphasis on the following items in Arabian cuisine: 1. Meat: lamb and chicken are the most used, beef and camel are also used to a lesser degree, other poultry is used in some regions, and, in coastal areas, fish. Pork is not commonly eaten--for Muslim Arabs, it is both a cultural taboo as well as being prohibited under Islamic law; many Christian Arabs also avoid pork as they have never acquired a taste for it. -

Sweets from the Middle East (Part 1)

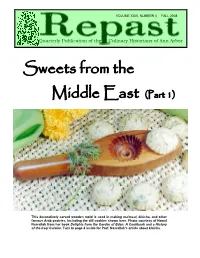

VOLUMEVOLUME XVI, XXIV, NUMBER NUMBER 4 4 FALL FALL 2000 2008 Quarterly Publication of the Culinary Historians of Ann Arbor Sweets from the Middle East (Part 1) This decoratively carved wooden mold is used in making ma'moul, kleicha, and other famous Arab pastries, including the dill cookies shown here. Photo courtesy of Nawal Nasrallah from her book Delights from the Garden of Eden: A Cookbook and a History of the Iraqi Cuisine. Turn to page 4 inside for Prof. Nasrallah’s article about kleicha. REPAST VOLUME XXIV, NUMBER 4 FALL 2008 Editor’s Note on Baklava Second Helpings Allowed! Charles Perry, who wrote the article “Damascus Cuisine” in our last issue, was the editor of a book Medieval Arab Cookery (Prospect Books, 2001) that sheds further light on the origins of baklava, the Turkish sweet discussed by Sheilah Kaufman in this issue. A dish described in a 13th-Century Baghdad cookery Sweets from the manuscript appears to be an early version of baklava, consisting of thin sheets of bread rolled around a marzipan-like filling of almond, sugar, and rosewater (pp. 84-5). The name given to this Middle East, Part 2 sweet was lauzinaj, from an Aramaic root for “almond”. Perry argues (p. 210) that this word gave birth to our term lozenge, the diamond shape in which later versions of baklava were often Scheduled for our Winter 2009 issue— sliced, even up to today. Interestingly, in modern Turkish the word baklava itself is used to refer to this geometrical shape. • Joan Peterson, “Halvah in Ottoman Turkey” Further information about the Baklava Procession mentioned • Tim Mackintosh-Smith, “A Note on the by Sheilah can be found in an article by Syed Tanvir Wasti, Evolution of Hindustani Sweetmeats” “The Ottoman Ceremony of the Royal Purse”, Middle Eastern Studies 41:2 (March 2005), pp. -

5. RICE DISHES Repicesbyrachel.Com

repicesbyrachel.com 5. RICE DISHES Unlike the many sauce and stew recipes set forth in the previous sections, the following are dishes having rice as their base. They do not produce sauce and, other than the first recipe below, may be eaten with no accompaniment. The first recipe here is itself the accompaniment: plain white rice meant to be eaten, not by itself, but together with sauce dishes. A central feature of Iraqi rice cooking is the production of hkaka – a layer of crisp rice produced by slow cooking. This is similar to the Persian tadig, but whereas tadig is thick crisp rice served with no loose rice, the Iraqis would serve hkaka to- gether with the loose rice that produced it. In order to make good hkaka, it is re- quired that the chef use a high quality pot with thick walls that conducts heat well. A thin, poor pot will yield burned rice rather than nice, brown hkaka. Before the invention of non-stick coatings, such as Teflon, hkaka would stick to the inside surface of the pot and had to be scraped out of it. In Iraq, there was a special metal spatula, called a kifkir, invented for this purpose. The rice would then be served as a mound, sprinkled with pieces of hkaka, on a large serving dish. The invention of non-stick coating now allows for presentation of the beau- tiful hkaka cake: A cake-like shell of crisped rice, containing loose rice under- neath. Because Iraqi cuisine is meant to be brought to the table in serving dishes, as opposed to being served plated, each dinner guest has the added sat- isfaction of watching the server break into the hkaka cake with a spoon and scoop the light, fluffy rice underneath onto his plate, together with the hkaka. -

Culinary Historians of New York• JC Forkner, the Smyrna

• CULINARY HISTORIANS OF NEW YORK • Volume 21, No. 2 Spring 2008 J.C. Forkner, the Smyrna Fig, and His Fig Gardens By Georgeanne Brennan Photo courtesy Pop .C. FORKNER was a visionary developer in the early part of the L J aval 20th century who created a yeo- E man farmer’s paradise out of twelve ducational thousand acres of scrubby, hardpan, F country in Central California be- oundation. tween the young town of Fresno and the Sierra Foothills. Experienced in developing similar land elsewhere in the United States, he came West, looking for opportunity and dis- covered it. He could buy thousands of acres of parched land, subdivide them into 40 to 100 acre parcels, bring in water from the Sierras and J.C. Forkner, second from left, and one of his many fig trees, 1917. market the parcels as the American dream of the era—that of owning a only spindly weeds and tumbleweed small farm. And to make his offer could grow. In 1910 Forkner took more enticing, he added another an option on 6,000 acres of the land, IN THIS ISSUE component, a farming company and spent the next year researching that would plant figs, cultivate, and the land and its potential. Through From the Chair ...................... 2 market them for the owners. His drilling he discovered that trapped project manifested the curious mix of beneath the hardpan, which varied Amelia Scholar’s Grant .......... 3 capitalism, boosterism, and genuine from several inches to several feet in enthusiasm for community that dis- thickness, was rich, loamy soil. -

Arab and Persian Influences

ARAB AND PERSIAN INFLUENCES As a child in Sri Lanka I was always fascinated by the cars that passed on the street whose back seat passengers were curtained off from public gaze. I learned early that these were most likely to be cars belonging to a Moor family, the curtains there to provide privacy for women of the family. Moor meant a Sri Lankan Muslim. I don’t know how I knew it, but I understood that they were spice merchants and also owned jewellery businesses in the Pettah. In later years, my father told me that many of the butchers in the Central Market were Muslims, as Islam had no prohibitions on the killing of animals for meat (the pig excepted), whereas Buddhists and Hindus did. At that time I didn’t stop to wonder about the origins of this community, but the story of the relationships between the Arab peoples, Persians and Sri Lanka is fundamental to the story of the spice trade and the development also of Sri Lankan foodways. Trade in the Arabian Sea Trade between Sri Lanka and the Arab and Persian kingdoms (modern Iran, Iraq, Yemen, Saudi Arabia) was clearly well-established by the time the Sassanian Empire formalised diplomatic relations with the court at Anuradhapura in the 5th century CE and Persian merchants established a community there. But the relationship was of much longer standing and had developed from two sources. The first was the export from Sri Lanka of spices and gems, the latter emphasised in an Arab name for the country Jairtu-ul Yāqūt or the Island of Rubies.i Ninth and tenth century Muslim writers mention -

Repicesbyrachel.Com 4. OTHER CLASSICS

repicesbyrachel.com 4. OTHER CLASSICS 1. Mhasha (Array of stuffed vegetable skins) Every Arab country considers stuffed grape leaves to be part of its cuisine, as do the Turks and the Greeks (“Dolma” and “Dolmades”). The dish probably has its origins in the Ottoman culinary tradition, which explains its ubiquity in the Middle East. The Iraqi version, as with so many other dishes, is substantially more complex. First of all, the Iraqi dish involves stuffing many different kinds of vegetable skins, and not only grape leaves. Secondly, the filling itself is both complicated and delicate, making for a won- derful dish in both taste and presentation. Hashwa (Filling): 1 ¾ cups long grain, white basmati rice, washed and soaked for 30 minutes 1 lbs. medium-lean meat, cut into very small cubes 1 very large lemon 4 cloves garlic, finely diced ½ bunch mint leaves, washed and coarsely chopped Finely diced beet cores (see below) OR 1-2 heaping teaspoons tomato paste ½ teaspoon salt ½ teaspoon pepper ¼ cayenne 1 tablespoon corn oil Vegetable Skins: 2 large onions 10 silq leaves (“silq” is the Arabic word for the leaves known as chard, Swiss chard, or silverbeet) 10 grape leaves (Note: If silq is not available, use a total of 20 grape leaves) 3 medium size beets 2 fresh red pimento (“gamba”) peppers 1 large, firm tomato 1 kusa (zucchini or white squash), peeled Ingredients for cooking: Juice from 1 large lemon ½ cup red wine, sweetened with silan or sugar 1 heaping teaspoon tomato paste 2-3 tablespoons oil A few dashes salt Initial preparation: Peel and wash beets. -

Songs of Grief, Joy, and Tragedy Among Iraqi Jews

EXILED NOSTALGIA AND MUSICAL REMEMBRANCE: SONGS OF GRIEF, JOY, AND TRAGEDY AMONG IRAQI JEWS BY LILIANA CARRIZO DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2018 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Donna A. Buchanan, Chair Professor Gabriel Solis Associate Professor Christina Bashford Professor Kenneth M. Cuno ABSTRACT This dissertation examines a practice of private song-making, one whose existence is often denied, among a small number of amateur Iraqi Jewish singers in Israel. These individuals are among those who abruptly emigrated from Iraq to Israel in the mid twentieth century, and share formative experiences of cultural displacement and trauma. Their songs are in a mixture of colloquial Iraqi dialects of Arabic, set to Arab melodic modes, and employ poetic and musical strategies of obfuscation. I examine how, within intimate, domestic spheres, Iraqi Jews continually negotiate their personal experiences of trauma, grief, joy, and cultural exile through musical and culinary practices associated with their pasts. Engaging with recent advances in trauma theory, I investigate how these individuals utilize poetic and musical strategies to harness the unstable affect associated with trauma, allowing for its bodily embrace. I argue that, through their similar synaesthetic capability, musical and culinary practices converge to allow for powerful, multi-sensorial evocations of past experiences, places, and emotions that are crucial to singers’ self-conceptions in the present day. Though these private songs are rarely practiced by younger generations of Iraqi Jews, they remain an under-the-radar means through which first- and second-generation Iraqi immigrants participate in affective processes of remembering, self-making, and survival. -

Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

SURESHKUMAR MUTHUKUMARAN AN ECOLOGY OF TRADE: TROPICAL ASIAN CULTIVARS IN THE ANCIENT MIDDLE EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN SURESHKUMAR MUTHUKUMARAN Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History, University College London 2016 SUPERVISORS: K. RADNER D. FULLER 1 SURESHKUMAR MUTHUKUMARAN DECLARATION I, Sureshkumar Muthukumaran, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. __________________________________________________________ 2 SURESHKUMAR MUTHUKUMARAN ABSTRACT This thesis offers an ecological reading of long distance trade in the ancient world by investigating the anthropogenic movement of tropical Asian crops from South Asia to the Middle East and the Mediterranean. The crops under consideration include rice, cotton, citrus species, cucumbers, luffas, melons, lotus, taro and sissoo. ἦhἷΝ ‘ὈὄὁpiἵaliὅaὈiὁὀ’Ν ὁἸΝ εiἶἶlἷΝ EaὅὈἷὄὀΝ aὀἶΝ εἷἶiὈἷὄὄaὀἷaὀΝ aἹὄiἵὉlὈὉre was a sluggish process but one that had a significant impact on the agricultural landscapes, production patterns, dietary habits and cultural identities of peoples across the Middle East and the Mediterranean by the end of the 1st millennium BCE. This process substantially predates the so-called tropical crop-ἶὄivἷὀΝ ‘χἹὄiἵὉlὈὉὄalΝ ἤἷvὁlὉὈiὁὀ’Ν ὁἸΝ ὈhἷΝ ἷaὄlyΝ ἙὅlamiἵΝ pἷὄiὁἶΝ pὁὅiὈἷἶΝ ἴyΝ ὈhἷΝ hiὅὈὁὄiaὀΝ χὀἶὄἷwΝ WaὈὅὁὀΝ (1974-1983). The existing literature has, in fact, largely failed to appreciate the lengthy time-scale of this phenomenon whose origins lie in the Late Bronze Age. In order to contextualise the spread of tropical Asian crops to the Middle East and beyond, the history of crop movements is prefaced by a survey of long distance connectivity across maritime (Indian Ocean) and overland (Iranian plateau) routes from its prehistoric beginnings to the end of the 1st millennium BCE.