Sweets from the Middle East (Part 1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classics : Alwaysavailable Starters

CLASSICS: ALWAYS AVAILABLE DESTINATION MENU STARTERS Bergen Salmon Gravlax beet marinated, cured salmon Malossol Paddlefish Caviar (market price) Lamb Farikal Blini; traditional condiments lamb brisket & green cabbage stew in lamb consommé Tiger Prawns Frognerseteren’s Apple Cake poached & chilled, cocktail sauce puff pastry layered with spiced apple jam; whipped cream & berries Caesar Salad romaine, anchovies, parmesan, garlic croutons, traditional Caesar dressing DINNER MENU MAIN COURSES STARTERS Angus New York Strip Steak (9 oz) Caribbean Senses grilled to order; steak fries, beurre maître d’hôtel marinated exotic fruit with Cointreau Chairman’s Choice: Poached Norwegian Salmon Prosciutto & Melon fresh pickled cucumber and boiled potatoes aragula & cherry tomato salad Roasted Free Range Poulet de Bresse Crème of Halibut chef’s favorite mash, au jus saffron rice & julienne leeks SIDES Endive & Williams Pear Salad celery, almonds; grainy mustard & apple cider vinaigrette Steamed Vegetables; Green Beans; Baked Potato; Mashed Potato; Creamed Spinach; Rice Pilaf MAIN COURSES Lumache con Carciofi e Pomodoro Secco DESSERTS shell pasta with artichokes, guianciale (pork) & sundried tomato Crème Brûlée Grilled Swordfish Steak with Tomato Relish Bourbon vanilla on basil crusted fingerling potato; bois boudran sauce New York Cheesecake Cornish Game Hen strawberry, raspberry, blueberry raspberry sauce; chanterelle mushrooms, farro risotto Fromagerie Braised Beef Ribs homemade chutney, crackers, grapes & baguette peanut sauce & coconut; steamed rice Fresh Fruit Plate melon, pineapple & berries DESSERTS Today’s Ice Cream Selection or Sorbet Chocolate Volcano lemon curd, poppy seed tuile Vanilla Risotto SOMMELIER’ S RECOMMENDATION silken tofu, vanilla bean Wine Name $36 Wine Name $32 Country Country VEGETARIAN HIGHLIGHTS Brie in Crispy Phyllo candied pecan & cranberry compote Gluten‐free bread available upon request. -

OK PASSOVER PRODUCTS FOOD GUIDE 2020 ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES Aluminum 10" Round Pan Multipeel (O) Barkan Wine Cellars Ltd

OK PASSOVER PRODUCTS FOOD GUIDE 2020 ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES Aluminum 10" Round Pan Multipeel (O) Barkan Wine Cellars Ltd. Aluminum 3lb Large Oval Bakin Nalo Faser / Fibrous- cellulose Givon Vodka Aluminum 4 4/5" Round Pan casings with paper (O) Courvoisier SAS Aluminum 5lb X-large Oval Bak Nalo Ferm (O) XO Cognac Courvoisier Size: Aluminum 8" Angel Tube Pan Nalo Kranz-pure cellulose casings 700ml Lot: L9162JCG01, Aluminum 8" Round Pan (O) L6202JCG05 Aluminum Medium Oval Baking Nalo ML-pure cellulose casings Le Cognac de Napoleon P (O) XO Cognac Courvoisier Size: Nicole Home Collection Nalo M-pure cellulose casings 700ml Lot: L9162JCG01, (O) 8" Square Cake Pan Aluminum L6202JCG05 Nalo Net-fibrous casing with net 9" Square Deep Cake Pan- Matar Winery (O) alumin Arak Nalo Schmal / Cellulose- pure Aluminum 10" Angel Tube Royal Wine Corporation cellulose casings (O) Pan Alfasi - Mistico (MV) Nalo Top - cellulose casings with Aluminum 10" Round Pan ALUMINUM WRAP PRODUCTS paper (O) Aluminum 3lb Large Oval Bakin Betty Crocker NaloFashion (O) Aluminum 4 4/5" Round Pan 25Sq ft Aluminum Foil (O) OSKUDA 2101 (O) Aluminum 5lb X-large Oval Bak 37.5Sq ft Aluminum Foil (O) Pergament (O) Aluminum 8" Angel Tube Pan 75Sq ft Aluminum Foil (O) Rona (O) Aluminum 8" Round Pan Formula Brands Inc. Ronet (O) Aluminum Medium Oval Baking 25Sq ft Aluminum Foil (O) Rotex (O) P 37.5Sq ft Aluminum Foil (O) Texdalon (O) AROMATIC CHEMICALS 75Sq ft Aluminum Foil (O) Texdalon KSB - Semi Finished Crown Chemicals Pvt. Ltd. Guangzhou Huafeng Aluminum (O) Piperonal Foil Technologies Co Ltd. -

Great Food, Great Stories from Korea

GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIE FOOD, GREAT GREAT A Tableau of a Diamond Wedding Anniversary GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS This is a picture of an older couple from the 18th century repeating their wedding ceremony in celebration of their 60th anniversary. REGISTRATION NUMBER This painting vividly depicts a tableau in which their children offer up 11-1541000-001295-01 a cup of drink, wishing them health and longevity. The authorship of the painting is unknown, and the painting is currently housed in the National Museum of Korea. Designed to help foreigners understand Korean cuisine more easily and with greater accuracy, our <Korean Menu Guide> contains information on 154 Korean dishes in 10 languages. S <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Tokyo> introduces 34 excellent F Korean restaurants in the Greater Tokyo Area. ROM KOREA GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES FROM KOREA The Korean Food Foundation is a specialized GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES private organization that searches for new This book tells the many stories of Korean food, the rich flavors that have evolved generation dishes and conducts research on Korean cuisine after generation, meal after meal, for over several millennia on the Korean peninsula. in order to introduce Korean food and culinary A single dish usually leads to the creation of another through the expansion of time and space, FROM KOREA culture to the world, and support related making it impossible to count the exact number of dishes in the Korean cuisine. So, for this content development and marketing. <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Western Europe> (5 volumes in total) book, we have only included a selection of a hundred or so of the most representative. -

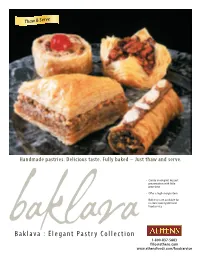

Athens Baklava Varieties Are Delicious on Their Own, but Try the Following Serving Suggestions to Create a Signature Item to Suit Your Menu

rve Se Thaw & Hurricane Shrimp Handmade pastries. Delicious taste. Fully baked – Just thaw and serve. • Create an elegant dessert presentation with little prep time • Offer a high-margin item • Bulk trays are available for in-store bakery/deli and foodservice Baklava : Elegant Pastry Collection 1-800-837-5683 [email protected] www.athensfoods.com/foodservice Classic Baklava Triangles (48 ct.) Pecan Blossoms (35 ct.) Chocolate Almond Rolls (45 ct.) Classic Baklava Rectangles (72 ct.) This classic treat contains a rich blend of spiced nuts Flaky fillo layers bursting with glazed natural pecans, Hand-rolled fillo tubes filled with a delicate blend Our delicious baklava is a sumptuous treat for any layered in sheets of crisp, flaky Athens Fillo® Dough, almonds and walnuts. Topped with honey syrup and of ground and chopped walnuts and sweet occasion. Rich blend of spiced nuts layered between finished with a sweet honey syrup. Scrumptious! whole pecans. Irresistible! chocolate. Baked crispy and then glazed. Finished crisp and flaky sheets of Athens Fillo® Dough, finished with hand-piped chocolate and natural sliced with a sweet honey syrup. Classic! almonds. As beautiful as they are delicious! elegant and Handmade delicious Appearance, Sensational Flavors, Excellentdessert Profitability. specialties Athens presents the finest collection of dessert specialties you’ll find anywhere - our collection has something for everyone. Beautiful presentation, delectable combinations, ready to serve, and with a high profit margin. You’ll love our sweet and -

General Directions

20 GENERAL DIRECTIONS TIME PROCEDURE NOTES active / inactive MIX by hand* combine A in a bowl, and mix to a shaggy mass; autolyse 30 min; add see Hand Mixing, page 5 min / 30 min B, and mix until homogeneous; transfer to a lightly oiled tub or bowl, 3·116 and cover well with a lid or plastic wrap by machine* combine A in mixer’s bowl, and mix on low speed to a shaggy mass; see Machine Mixing 37–41 min autolyse 20–30 min; add B, and mix on medium speed to medium options, page 65 gluten development; turn off mixer, add C, and mix on low speed until fully incorporated; transfer to a lightly oiled tub or bowl, and cover well with a lid or plastic wrap BULK FERMENT by hand* 4 h total; 6 folds (1 fold every 30 min after the first hour), 30 min rest see How to Perform a 5 min / 4 h after final fold; after the second fold, turn off mixer, add C; mix with Four-Edge Fold, page your hands using a squeeze, pull, and fold-over motion; check for full 3·129; see Gluten Devel- gluten development using the windowpane test opment, page 3·89 by machine* 2½ h total; 2 folds (1 fold every hour after the first hour), 30 min rest 5 min / 2½ h after final fold; check for full gluten development using the window- pane test DIVIDE/SHAPE divide lg boule/bâtard sm boule/bâtard roll miche see How to Divide Your 0–7 min do not divide 500 g 75 g do not divide Dough, page 3·136 preshape boule/bâtard boule/bâtard roll boule see shaping boules and 1–7 min rest 20 min 20 min 20 min 20 min bâtards, pages 3·152–155, 20 min and rolls, page 3·176 shape boule/bâtard boule/bâtard -

Considerations About Semitic Etyma in De Vaan's Latin Etymological Dictionary

applyparastyle “fig//caption/p[1]” parastyle “FigCapt” Philology, vol. 4/2018/2019, pp. 35–156 © 2019 Ephraim Nissan - DOI https://doi.org/10.3726/PHIL042019.2 2019 Considerations about Semitic Etyma in de Vaan’s Latin Etymological Dictionary: Terms for Plants, 4 Domestic Animals, Tools or Vessels Ephraim Nissan 00 35 Abstract In this long study, our point of departure is particular entries in Michiel de Vaan’s Latin Etymological Dictionary (2008). We are interested in possibly Semitic etyma. Among 156 the other things, we consider controversies not just concerning individual etymologies, but also concerning approaches. We provide a detailed discussion of names for plants, but we also consider names for domestic animals. 2018/2019 Keywords Latin etymologies, Historical linguistics, Semitic loanwords in antiquity, Botany, Zoonyms, Controversies. Contents Considerations about Semitic Etyma in de Vaan’s 1. Introduction Latin Etymological Dictionary: Terms for Plants, Domestic Animals, Tools or Vessels 35 In his article “Il problema dei semitismi antichi nel latino”, Paolo Martino Ephraim Nissan 35 (1993) at the very beginning lamented the neglect of Semitic etymolo- gies for Archaic and Classical Latin; as opposed to survivals from a sub- strate and to terms of Etruscan, Italic, Greek, Celtic origin, when it comes to loanwords of certain direct Semitic origin in Latin, Martino remarked, such loanwords have been only admitted in a surprisingly exiguous num- ber of cases, when they were not met with outright rejection, as though they merely were fanciful constructs:1 In seguito alle recenti acquisizioni archeologiche ed epigrafiche che hanno documen- tato una densità finora insospettata di contatti tra Semiti (soprattutto Fenici, Aramei e 1 If one thinks what one could come across in the 1890s (see below), fanciful constructs were not a rarity. -

Passover 2020 Catering Packages Minimum 4 People ORDERS DUE by WEDNESDAY, APRIL 1

Passover 2020 Catering Packages Minimum 4 People ORDERS DUE BY WEDNESDAY, APRIL 1 Each Package Includes: 1 Box Matzah Chicken Soup with Matzah Ball Gefilte Fish with Purple Horseradish Choice of Salad Rosemary Fingerling Potatoes, Mashed Potato, Potato Gratin, or Potato Kugel Roasted White Asparagus, Baby Carrot, & Cauliflower Medley Choice of Entrée Chicken $40/person Roast Chicken, BBQ Chicken, Pargiot (+$2), Honey Garlic Thigh (+$2) or Lemon French Breast (+$4) Fish $43/person Pan Seared Salmon, Teriyaki Salmon, Pan Fried Flounder, or Halibut (+$8) Meat $46/person Spanish Meatballs, Boeuf Bourguignon, Smoked Brisket (+$2), French Onion Brisket (+$2), or Marinated London Broil (+$2) Duet of Chicken & Meat $55/person Chicken, Meat, & Fish $64/person ***INDIVIDUALLY PACKAGED MEALS AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST*** Adam Rafalowicz, Catering Manager C: 914-391-9050 [email protected] 108 Prospect Street Stamford CT 06901 W: 203-614-8777 www.613restaurant.com Passover 2020 Catering Menu A la Carte ORDERS DUE BY WEDNESDAY, APRIL 1 Soup Chicken Chicken Vegetable Soup - $14.99/qt Pargiot - $22.99/lb Potato Leek Soup - $14.99/qt Grilled BBQ Chicken - $20.99/lb Quinoa Vegetable Soup - $14.99/qt Honey & Garlic Chicken Thigh - $22.99/lb Matzah Ball - $2/each Fried Chicken Cutlet - $20.99/lb Teriyaki Chicken - $20.99/lb Salad Whole Roast Chicken - $17.99/each Prices Per Bowl 64oz/128oz Lemon French Breast - $24.99/lb Caesar Salad - $30/$55 Roasted Beet Salad - $30/$55 Meat Mixed Greens Salad - $30/$55 Smoked Texas Brisket - $32.99/lb Kale & Quinoa -

To-Go Menu SALADS with GARLIC SAUCE CHICKEN SHAWERMA STREET

SAMPLERS ATHENA’S WRAPS *ADD HUMMUS AND SALAD FOR $2* V DIP SAMPLER ......................................... 7 HUMMUS, GRECIAN DIP, BABA GHANOUSH & LABNEH CHICKEN SHAWERMA ............................... 7 8 ATHENA’S SAMPLER FOR ONE ................ 7 GRECIAN DIP, LETTUCE & TOMATOES FALAFEL, FRIED EGGPLANT, KIBBEH & MEAT GRAPE LEAF GYRO .............................................................. 7 8 GREEK MEZA V ......................................... 4 GRECIAN DIP, LETTUCE, TOMATOES & ONIONS TOMATOES, CUCUMBERS, ONIOINS, TURNIPS, PICKLES & OLIVES BEEF KOFTA ................................................ 7 MEAT FEAST ................................................. 25 GRECIAN DIP, LETTUCE, TOMATOES & ONIONS CHOOSE FIVE DIFFERENT SKEWER ITEMS BEEF SHAWERMA STREET ....................... 11 GRILLED 12-INCH BEEF WRAP, CUT INTO PIECES & SERVED To-Go Menu SALADS WITH GARLIC SAUCE CHICKEN SHAWERMA STREET .............. 10 GRILLED 12-INCH CHICKEN WRAP, CUT INTO PIECES & SERVED FETA SALAD .................................................. 6 WITH GARLIC SAUCE LETTUCE, FETA CHEESE & ATHENA’S SPECIAL SALAD DRESSING HALLOUMI CHEESE V ........................... 8 GREEK SALAD ............................................... 7 DRIED MINT, TOMATOES & BLACK OLIVES LETTUCE, FETA CHEESE, TOMATOES, CUCUMBERS, BLACK OLIVES & EGGPLANT V ............................................. 8 ATHENA’S SPECIAL SALAD DRESSING ARABIC SALAD .............................................. 7 FETA CHEESE, ONIONS & TOMATOES V HOURS FRESH-CUT TOATOES, CUCUMBERS, PARSLEY, -

Master List - Lectures Available from Culinary Historians

Master List - Lectures available from Culinary Historians The Culinary Historians of Southern California offer lectures on food and cultures from ancient to contemporary. Lectures that are well suited for young audiences are prefaced by a “Y” in parentheses, illustrated lectures with an “I”. Most lectures can be combined with a tasting of foods relevant to the topic. * * * Feride Buyuran is a chef and historian, as well as the author of the award-winning "Pomegranates & Saffron: A Culinary Journey to Azerbaijan." A Culinary Journey to Azerbaijan - The cooking of the largest country in the Caucasus region is influenced by Middle Eastern and Eastern European cuisines. This lecture explores the food of Azerbaijan within its historical, social, and cultural context. Feride Buyuran will highlight the importance of the Silk Road in the formation of the traditional cuisine and the dramatic impact of the Soviet era on the food scene in the country. (I) * * * Jim Chevallier began his food history career with a paper on the shift in breakfast in eighteenth century France. As a bread historian, he has contributed to the Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America, and his work on the baguette and the croissant has been cited in both books and periodicals. His most recent book is "A History of the Food of Paris: From Roast Mammoth to Steak Frites." Aside from continuing research into Parisian food history, he is also studying French bread history and early medieval food. Dining Out Before Restaurants Existed - Starting as early as the thirteenth century, inns, taverns and cabarets sold food that was varied and sometimes even sophisticated. -

Where the Flavours of the World Meet: Malabar As a Culinary Hotspot

UGC Approval No:40934 CASS-ISSN:2581-6403 Where The Flavours of The World Meet: CASS Malabar As A Culinary Hotspot Asha Mary Abraham Research Scholar, Department of English, University of Calicut, Kerala. Address for Correspondence: [email protected] ABSTRACT The pre-colonial Malabar was an all-encompassing geographical area that covered the entire south Indian coast sprawling between the Western Ghats and Arabian Sea, with its capital at Kozhikkode. When India was linguistically divided and Kerala was formed in 1956, the Malabar district was geographically divided further for easy administration. The modern day Malabar, comprises of Kozhikkode, Malappuram and few taluks of Kasarkod, Kannur, Wayanad, Palakkad and Thrissur. The Malappuram and Kozhikkod region is predominantly inhabited by Muslims, colloquially called as the Mappilas. The term 'Malabar' is said to have etymologically derived from the Malayalam word 'Malavaram', denoting the location by the side of the hill. The cuisine of Malabar, which is generally believed to be authentic, is in fact, a product of history and a blend of cuisines from all over the world. Delicacies from all over the world blended with the authentic recipes of Malabar, customizing itself to the local and seasonal availability of raw materials in the Malabar Coast. As an outcome of the age old maritime relations with the other countries, the influence of colonization, spice- hunting voyages and the demands of the western administrators, the cuisine of Malabar is an amalgam of Mughal (Persian), Arab, Portuguese,, British, Dutch and French cuisines. Biriyani, the most popular Malabar recipe is the product of the Arab influence. -

2020 Annual Recipe SIP.Pdf

SPECIAL COLLECTOR’SEDITION 2020 ANNUAL Every Recipe from a Full Year of America’s Most Trusted Food Magazine CooksIllustrated.com $12.95 U.S. & $14.95 CANADA Cranberry Curd Tart Display until February 22, 2021 2020 ANNUAL 2 Chicken Schnitzel 38 A Smarter Way to Pan-Sear 74 Why and How to Grill Stone 4 Malaysian Chicken Satay Shrimp Fruit 6 All-Purpose Grilled Chicken 40 Fried Calamari 76 Consider Celery Root Breasts 42 How to Make Chana Masala 77 Roasted Carrots, No Oven 7 Poulet au Vinaigre 44 Farro and Broccoli Rabe Required 8 In Defense of Turkey Gratin 78 Braised Red Cabbage Burgers 45 Chinese Stir-Fried Tomatoes 79 Spanish Migas 10 The Best Turkey You’ll and Eggs 80 How to Make Crumpets Ever Eat 46 Everyday Lentil Dal 82 A Fresh Look at Crepes 13 Mastering Beef Wellington 48 Cast Iron Pan Pizza 84 Yeasted Doughnuts 16 The Easiest, Cleanest Way 50 The Silkiest Risotto 87 Lahmajun to Sear Steak 52 Congee 90 Getting Started with 18 Smashed Burgers 54 Coconut Rice Two Ways Sourdough Starter 20 A Case for Grilled Short Ribs 56 Occasion-Worthy Rice 92 Oatmeal Dinner Rolls 22 The Science of Stir-Frying 58 Angel Hair Done Right 94 Homemade Mayo That in a Wok 59 The Fastest Fresh Tomato Keeps 24 Sizzling Vietnamese Crepes Sauce 96 Brewing the Best Iced Tea 26 The Original Vindaloo 60 Dan Dan Mian 98 Our Favorite Holiday 28 Fixing Glazed Pork Chops 62 No-Fear Artichokes Cookies 30 Lion’s Head Meatballs 64 Hummus, Elevated 101 Pouding Chômeur 32 Moroccan Fish Tagine 66 Real Greek Salad 102 Next-Level Yellow Sheet Cake 34 Broiled Spice-Rubbed 68 Salade Lyonnaise Snapper 104 French Almond–Browned 70 Showstopper Melon Salads 35 Why You Should Butter- Butter Cakes 72 Celebrate Spring with Pea Baste Fish 106 Buttermilk Panna Cotta Salad 36 The World’s Greatest Tuna 108 The Queen of Tarts 73 Don’t Forget Broccoli Sandwich 110 DIY Recipes America’s Test Kitchen has been teaching home cooks how to be successful in the kitchen since 1993. -

Desserts Drink Special

Orders must be requested by 4 p.m. on Monday, December 28 and pickup is available at valet on Thursday, December 31 from 4 p.m.-7 p.m. Prices are subject to sales tax. Return your form to [email protected], fax it to (561) 776-4943, or drop it off at valet. Platters (each serves 2) PRICE QTY NEEDED Siberian Sturgeon Caviar, two ounces $110 Chives, sour cream, grated, egg, red onion, one dozen blini, bagel chips Grand Smoked Fish Platter, serves two Smoked salmon, sable, sturgeon, whitefish chubbs, four bagels, cream cheese, sliced tomato, $60 capers, red onion 6 Large Florida Stone Crab Claws $60 Mustard sauce, cocktail sauce, lemon 8 Jumbo Shrimp Cocktail $32 Cocktail sauce, lemon Chef Mike’s Favorite Artisanal Cheeses $36 Five high-end cheeses, dried fruit, chutney, crostini, Yes! Honey Chef Mike’s Favorite Cured Meats $48 Prosciutto di Parma, foie gras pâté, Spanish hams and chorizo, breadsticks, crostini, olives 12 Crispy Wings Your Style Choose from truffle-Parmesan, Buffalo, or Yes! Honey butter with za’atar, served with carrots, celery, $18 blue cheese dressing Seasonal Crudité & Roasted Veggie Mezze Board $28 Hummus, avocado yogurt dip, baba ganoush, red pepper spread Half Tray of Housemade RigaTONY Vodka from Solstice Italian $42 Garlic bread, Parmesan cheese One Dozen Solstice Italian Meatballs $48 House red sauce, garlic bread, Parmesan cheese Desserts PRICE QTY NEEDED Assorted Pastry Box, five pieces $22 6 Chocolate-Covered Strawberries $12 Drink Special PRICE QTY NEEDED Piper-Heidsieck Cuvée Brut Champagne $35 Member Name: Mbr. #: Email Address: Telephone: .