University of Copenhagen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Games Ancient and Oriental and How to Play Them, Being the Games Of

CO CD CO GAMES ANCIENT AND ORIENTAL AND HOW TO PLAY THEM. BEING THE GAMES OF THE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS THE HIERA GRAMME OF THE GREEKS, THE LUDUS LATKUNCULOKUM OF THE ROMANS AND THE ORIENTAL GAMES OF CHESS, DRAUGHTS, BACKGAMMON AND MAGIC SQUAEES. EDWARD FALKENER. LONDON: LONGMANS, GEEEN AND Co. AND NEW YORK: 15, EAST 16"' STREET. 1892. All rights referred. CONTENTS. I. INTRODUCTION. PAGE, II. THE GAMES OF THE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS. 9 Dr. Birch's Researches on the games of Ancient Egypt III. Queen Hatasu's Draught-board and men, now in the British Museum 22 IV. The of or the of afterwards game Tau, game Robbers ; played and called by the same name, Ludus Latrunculorum, by the Romans - - 37 V. The of Senat still the modern and game ; played by Egyptians, called by them Seega 63 VI. The of Han The of the Bowl 83 game ; game VII. The of the Sacred the Hiera of the Greeks 91 game Way ; Gramme VIII. Tlie game of Atep; still played by Italians, and by them called Mora - 103 CHESS. IX. Chess Notation A new system of - - 116 X. Chaturanga. Indian Chess - 119 Alberuni's description of - 139 XI. Chinese Chess - - - 143 XII. Japanese Chess - - 155 XIII. Burmese Chess - - 177 XIV. Siamese Chess - 191 XV. Turkish Chess - 196 XVI. Tamerlane's Chess - - 197 XVII. Game of the Maharajah and the Sepoys - - 217 XVIII. Double Chess - 225 XIX. Chess Problems - - 229 DRAUGHTS. XX. Draughts .... 235 XX [. Polish Draughts - 236 XXI f. Turkish Draughts ..... 037 XXIII. }\'ci-K'i and Go . The Chinese and Japanese game of Enclosing 239 v. -

Temporal Difference Learning Algorithms Have Been Used Successfully to Train Neural Networks to Play Backgammon at Human Expert Level

USING TEMPORAL DIFFERENCE LEARNING TO TRAIN PLAYERS OF NONDETERMINISTIC BOARD GAMES by GLENN F. MATTHEWS (Under the direction of Khaled Rasheed) ABSTRACT Temporal difference learning algorithms have been used successfully to train neural networks to play backgammon at human expert level. This approach has subsequently been applied to deter- ministic games such as chess and Go with little success, but few have attempted to apply it to other nondeterministic games. We use temporal difference learning to train neural networks for four such games: backgammon, hypergammon, pachisi, and Parcheesi. We investigate the influ- ence of two training variables on these networks: the source of training data (learner-versus-self or learner-versus-other game play) and its structure (a simple encoding of the board layout, a set of derived board features, or a combination of both of these). We show that this approach is viable for all four games, that self-play can provide effective training data, and that the combination of raw and derived features allows for the development of stronger players. INDEX WORDS: Temporal difference learning, Board games, Neural networks, Machine learning, Backgammon, Parcheesi, Pachisi, Hypergammon, Hyper-backgammon, Learning environments, Board representations, Truncated unary encoding, Derived features, Smart features USING TEMPORAL DIFFERENCE LEARNING TO TRAIN PLAYERS OF NONDETERMINISTIC BOARD GAMES by GLENN F. MATTHEWS B.S., Georgia Institute of Technology, 2004 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE ATHENS,GEORGIA 2006 © 2006 Glenn F. Matthews All Rights Reserved USING TEMPORAL DIFFERENCE LEARNING TO TRAIN PLAYERS OF NONDETERMINISTIC BOARD GAMES by GLENN F. -

Fatehpur Sikri

Fatehpur Sikri Fatehpur Sikri Fort Fatehpur Sikri fort and city was built by Mughal Emperor Akbar. He made it his capital and later shifted his capital to Agra. It was the same place where Akbar declared his nine jewels or Navaratna. The city is built on Mughal architecture. This tutorial will let you know about the history of Fatehpur Sikri along with the structures present inside. You will also get the information about the best time to visit it along with how to reach the city. Audience This tutorial is designed for the people who would like to know about the history of Fatehpur Sikri along with the interiors and design of the city. This city is visited by many people from India and abroad. Prerequisites This is a brief tutorial designed only for informational purpose. There are no prerequisites as such. All that you should have is a keen interest to explore new places and experience their charm. Copyright & Disclaimer Copyright 2016 by Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. All the content and graphics published in this e-book are the property of Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. The user of this e-book is prohibited to reuse, retain, copy, distribute, or republish any contents or a part of contents of this e-book in any manner without written consent of the publisher. We strive to update the contents of our website and tutorials as timely and as precisely as possible, however, the contents may contain inaccuracies or errors. Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. provides no guarantee regarding the accuracy, timeliness, or completeness of our website or its contents including this tutorial. -

The Architecture of Fatehpur Sikri

THE ARCHITECTURE OF FATEHPUR SIKRI Dissertation Submitted for the Degree of M. Phil. BY SHIVANI SINGH Under the Supervision of DR. J. V. SINGH AGRE CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) MAY, 1995 DS2558 ,i.k *i' ••J-jfM/fjp ^6"68 V :^;j^^»^ 1 6 FEB W(> ;»^ j IvJ /\ S.'D c;v^•c r/vu ' x/ ^-* 3 f«d In Coflnp«< CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY TELEPHONE : 5546 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH, U.P. M«r 31, 1995 Thl« Is to certify that tiM M.Phil 4iM«rt«tion •Btitlad* *Arca>lt<ictar« of FstrtaHir aikri* miikm±ttmd by Mrs. Shlvonl ftlagti 1» Iwr odgi&al woxk and is soitsbls for sulMiiisslon. T (J«g^ Vlr Slagh Agrs) >8h«x«s* • ****•**********."C*** ******* TO MY PARENTS ** **lr*******T*************** ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to express my profound gratitude to my supervisor Dr. J.V, Singh Agre for his unstinted guid ance, valuable suggestions and critical analysis of the present study. I am also grateful to- a) The Chairman, Department of Histoiry, A,i-i.u., Aligarh, b) The ICHR for providing me financial assistance and c) Staff of the Research Seminar, Department of History, A.M.U., Aligarh. I am deeply thankful to my husband Rajeev for his cooperation and constant encouragement in conpleting the present work. I take my responsibility for any mistak. CW-- ^^'~ (SHIVANI SINGH) ALIGARH May'9 5, 3a C O N T E NTS PAGE NO. List of plates i List of Ground Plan iii Introduction 1 Chapter-I t HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 2 Chapter-II: MAIN BUILDINGS INSIDE THE FORT 17 Chapter-Ill; BUILDINGS OUTSIDE THE FORT 45 Chapter-IV; WEST INDIAN ( RAJPUTANA AND GUJARAT ) ARCHITECTURAL INFLUENCE ON THE BUIL DINGS OF FATEHPUR SIKRI. -

Pachisi Is a Traditional Indian Game Whose Origins Are Pachisi Is Cross and Circle Board Race Game, and Many Speculated to Go Back As Early As the Fourth Century

Pachisi is a traditional indian game whose origins are Pachisi is cross and circle board race game, and many speculated to go back as early as the fourth century. Is has games adapted from it gained popularity in the West, a twin game, called Chaupar, that was once considered to commercialized with such names as Parcheesi, Sorry! and be a game for the nobility, while Pachisi, with its slightly Ludo. The original name, however, derives from the word simpler rules, was thought of as a game for the common 'pachis', which means 'twenty-five' in hindi. The game is people. traditionally played with a board embroidered on cloth and using cowries instead of dice. Pachisi is played by two participants, each choosing a color, THE GAME or by two doubles, one taking the yellow and black pieces In his turn each participant will roll once, and is allowed to and the other, the red and green. Each participant must move one piece a number of spaces equal to the result. On guide his four pieces from the central, go around the board his first turn, he will be able to free a piece from the counterclockwise and return to the Charkoni. The first Charkoni no matter the result he got. player (or double) to do so is considered winner. The participant may have any number of free pieces (pieces A ROLL out of teh Charkoni) as she can, and may also refuse to During the game, it will be asked for the participant to cast a move on his turn, thus ending it. -

A Handbook to Agra and the Taj, Sikandra, Fatehpur-Sikri and the Neighbourhood

A HANDBOOK TO AGRA AND THE TAJ SIKANDRA, FATEHPUR-SIKRI, AND THE NEIGHBOURHOOD ija>b ;a .^-—-^ A HANDBOOK TO AGRA AND THE TAJ SIKANDRA, FATEHPUR-SIKRI AND THE NEIGHBOURHOOD BY E. B. HAVELL, A.R.C.A. PRINCIPAL, GOVERNMENT SCHOOL OF ART, CALCUTTA FELLOW OF THE CALCUTTA UNIVERSITY WITH 14 ILLUSTRATIONS FROM PHOTOGRAPH*' AND 4 PLANS LONGMANS, GREEN, AND"^ 39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON NEW YORK AND BOMBAY 1904 All right* reserved A3H3 FEB 21 1966 " ^*?/Ty OF TO*$£^ 10 516 5 4 PREFACE This little book is not intended for a history or archaeological treatise, but to assist those who visit, or have visited, Agra, to an intelligent under- standing of one of the greatest epochs of Indian Art. In the historical part of it, I have omitted unimportant names and dates, and only attempted to give such a sketch of the personality of the greatest of the Great Moguls, and of the times in which they lived, as is necessary for an apprecia- tion of the wonderful monuments they left behind them. India is the only part of the British Empire where art is still a living reality, a portion of the people's spiritual possessions. We, in our ignorance and affectation of superiority, make efforts to improve it with Western ideas ; but, so far, have only succeeded in doing it incalculable harm. It would be wiser if we would first attempt to understand it. Among many works to which I owe valuable information, I should name especially Erskine's vi Preface ; translation of Babar's " Memoirs " Muhammad ; Latif's " Agra, Historical and Descriptive " and Edmund Smith's " Fatehpur-Sikri." My acknow- ledgments are due to Babu Abanindro Nath Tagore, Mr. -

L'inde, Microcosme Ludique ?

L’inde, microcosme ludique ? Michel Van Langendonckt, Sciences et techniques du jeu, Haute Ecole de Bruxelles – Haute Ecole Spaak L’Inde est-elle un microcosme ludique ? Autrement dit, les principaux jeux du monde sont-ils indiens ou originaires d’Inde ? Y sont-ils pratiqués aujourd’hui ? A défaut, quelles seraient les spécificités des jeux indiens ou originaires d’Inde, que nous dit l’ethno-ludisme du subcontinent indien ? Telles sont les questions que nous nous posons. Quelques éléments de réponses apparaitront au cours d’un survol socio-historique des jeux inventés ou adoptés en Inde. D’une compilation des recherches antérieures consacrées aux jeux indiens et d’un relevé personnel émergent des évocations littéraires, des représentations et du matériel de jeux. Ils sont plus particulièrement issus de six sources : 1° Les jeux de dés et de course (ou de parcours symboliques) évoqués dans les textes sanskrits. 2° Les représentations sculptées de Shiva et Pârvâti jouant (IIe – XIe siècle, Inde centrale) . 3° L’album de croquis « Vie et coutumes indiennes » (fin du XVIIIe siècle, nord de l’Inde). 4° Les tabliers de jeux gravés dans le sol au Karnataka (VIIIe-XXe siècle, sud de l’Inde). 5° Un coffret multi-jeux du milieu du XIXe siècle (Mysore, sud de l’Inde). 6° Le relevé des pratiques de jeux traditionnels sur plateau réalisé en 1998-1999 dans l’ensemble de l’Inde, sous la direction de R.K Bhattacharya, I.L. Finkel et L.K. Soni (publié en 2011) Attitude ludique et créativité indienne Fig. 2 – Colloque « Jeux indiens et originaires d’Inde » (Haute Ecole de Bruxelles, 13 décembre 2013) En ce qui concerne l’attitude ludique et les jouets en général, la créativité dans la fabrication des objets de jeu demeure une constante de la culture indienne. -

Road Maps for the Soul

Road Maps for the Soul - a critical reading of five North Indian 72-square gyān caupaṛ boards by Jacob Schmidt-Madsen, stud. phil. यतत्रानक唃न क्वच椿दचꤿ हग न तत चतष्ठत्यथककथ यतत्रापकस्तदनन न बहवस्तत नककथ ऽचꤿ 椿त्रानन इत त 椿म륌न रजचनचदवस륌 दकलयनत्राचववत्राक륌 कत्राल唃 कलक भवनफलकन न कक्रीदचत पत्राच贿सत्रार唃थ Where once there were many in a house, there now remains only one, and where there is one, there are many later, and not even one in the end; and thus, shaking night and day like two dice, Time, the expert, plays with living pieces on the gameboard of the earth. - (Bhartṛhari, Śatakatraya 3.42, 5th/7th cent. CE) submitted as M.A. Specialized Topic Paper, University of Copenhagen, January 2013 1 Contents Introduction . p. 2 The World in a Game . p. 4 The Caupaṛ of Knowledge . p. 7 Analysis of Gyān Caupaṛ Boards . p. 9 Structure . p. 11 Cosmogony . p. 12 Cosmography . p. 15 Doctrine of Karma . p. 17 Summary . p. 19 Further Perspectives . p. 20 Conclusion . p. 22 Bibliography . p. 23 Appendix A: Critical Reading of Boards abcde . p. 26 Appendix B: Diagram of Preferred Readings . p. 52 Appendix C: Original Boards (abcde) . p. 53 Introduction Most people who grew up before the explosion of the games industry in the 1980s probably know the game of Snakes and Ladders (popularized as Chutes and Ladders in the US). The design is as simple as it is dull. The players take turns rolling a die, moving their single pawn forward accordingly, competing to be the first to reach the final square of the board. -

American Games: a Historical Perspective / by Bruce Whitehill

American Games: A Historical Perspective / by Bruce Whitehill istorians investigating board games of the world have traditionally examined ancient or early games, using artifacts, drawings, and available text. From this, Hthey hoped to learn more about the cultures in which these games flourished, how the games moved from one territory to another (trade routes), and how they chan- ged and evolved in different cultures. Traditional classic games such as chess, checkers (draughts), Mancala, Pachisi, Mill (Mühle or Nine Mens Morris), Fox and Geese, and the Game of Goose, among others, have been studied in great detail by many scholars. Some of these games were played on quite elaborate, carved wooden boards, and, as such, they were available only to a privileged few. In the middle 1800s, however, advances in lithography and in techniques of the mass production of printed matter allowed games to be commercially produced in large quantities. They were also inexpensive enough to be affordable by the less affluent. This meant that games could reach a larger portion of the population, and become a staple in more homes. What purposes have games served in society? Were they recreational or were they intended as educational or instructional instruments? And who manufactured and sup- plied these games to the public? In the United States, a study of games poses one immediate limit for the researcher: the term “ancient” hardly applies to a country that was not formally “discovered” until 1492. Well into the 1800s, most board games played in North America were of European origin. Culin (1907) lists the board games played by the American Indians under the hea- ding “European games,” though games he categorized as “dice games” are actually board games that use dice to determine movement. -

History of Pachisi -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

History of Pachisi The national board game of India is known as Pachisi, or the game of Twenty-Five. The name comes from the Indian word pachis, which means twenty- five, the highest score that can be earned in the game. It has been played for more than 1,200 years. Although the game of Parcheesi is related to Pachisi, Parcheesi is the U.S. version of the game, and is much simpler. Pachisi actually came from the older game called Chaupar, which is still played in India today. It is said that the Indian Emperor Akbar I played Chaupar on courts of red and white marble squares that represented a pachisi board. His playing pieces were sixteen slaves from his harem, or collection of beautiful women. Akbar sat on his throne and threw some cowrie shells, which are used in the game to determine how many squares the playing pieces may move. Some of these life-size boards still remain in India today. The traditional Pachisi board is a woven cross-shaped cloth marked by embroidered squares, but the modern version is often made of wood. Each arm of the cross has eight squares, and three squares of each arm are decorated in some way to indicate that they are “castles.” All four arms of the cross meet in the middle, which is called the “Charkoni.” The 16 traditional playing pieces are beehive-shaped, and come in four colors: black, green, red and yellow. Cowrie shells are thrown to show how many squares to move, although modern versions of the game often substitute dice. -

Traditional Cosmological Symbolism in Ancient Board Games

Traditional Cosmological Symbolism in Ancient Board Games Gaspar Pujol Nicolau ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tesisenxarxa.net) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX. No s’autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tesisenred.net) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR. No se autoriza la presentación de su contenido en una ventana o marco ajeno a TDR (framing). Esta reserva de derechos afecta tanto al resumen de presentación de la tesis como a sus contenidos. En la utilización o cita de partes de la tesis es obligado indicar el nombre de la persona autora. -

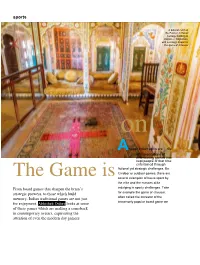

The Game Is Several Examples of Hours Spent by the Elite and the Masses Alike from Board Games That Sharpen the Brain’S Indulging in Sporty Challenges

sports A palatial room at the Patwon ki Haveli heritage building in Jaisalmer, Rajasthan, with a vintage board for the game of Chausar on Ancient Indian epics are rife with descriptions of entertaining games that kept people of that time entertained through fictional yet strategic challenges. Be it indoor or outdoor games, there are The Game is several examples of hours spent by the elite and the masses alike From board games that sharpen the brain’s indulging in sporty challenges. Take strategic prowess, to those which build for example the game of chausar, memory, Indian traditional games are not just often called the ancestor of the for enjoyment. Abhishek Dubey looks at some immensely popular board game we of these games which are making a comeback in contemporary avatars, captivating the attention of even the modern day gamers the game used to be played with now call Ludo. Played by four players a dice on a checkered board, but on a cross-shaped board, the game without black and white squares. involves the strategic movement of Some say chaturanga (quadripartite) markers - four of which are allotted to was the original chess game. In every player. This is the game that Sanskrit, chatur means four and anga finds a mention even in the Indian means limbs, that were symbolic epic, Mahabharata. The modern of the four branches of an army. Just avatar, Ludo, is now one of the most like an army from the ancient times, popularly enjoyed game on online the game used pieces shaped like platforms with thousands of games elephants, chariots, horses and being hosted online.