Board and Table Games from Many Civilizations. 2Nd Ed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concord Mcnair Scholars Research Journal

Concord McNair Scholars Research Journal Volume 9 (2006) Table of Contents Kira Bailey Mentor: Rodney Klein, Ph.D. The Effects of Violence and Competition in Sports Video Games on Aggressive Thoughts, Feelings, and Physiological Arousal Laura Canton Mentor: Tom Ford, Ph.D. The Use of Benthic Macroinvertebrates to Assess Water Quality in an Urban WV Stream Patience Hall Mentor: Tesfaye Belay, Ph.D. Gene Expression Profiles of Toll-Like Receptors (TLRs) 2 and 4 during Chlamydia Infection in a Mouse Stress Model Amanda Lawrence Mentor: Tom Ford, Ph.D. Fecal Coliforms in Brush Creek Nicholas Massey Mentor: Robert Rhodes Appalachian Health Behaviors Chivon N. Perry Mentor: David Matchen, Ph.D. Stratigraphy of the Avis Limestone Jessica Puckett Mentors: Darla Wise, Ph.D. and Darrell Crick, Ph.D. Screening of Sorrel (Oxalis spp.) for Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activity Sandra L. Rodgers Mentor: Jack Sheffler, M.F.A. Rembrandt’s Path to Master Painter Crystal Warner Mentor: Roy Ramthun, Ph.D. Social Impacts of Housing Development at the New River Gorge National River 2 Ashley L. Williams Mentor: Lethea Smith, M.Ed. Appalachian Females: Catalysts to Obtaining Doctorate Degrees Michelle (Shelley) Drake Mentor: Darrell Crick, Ph.D. Bioactivity of Extracts Prepared from Hieracium venosum 3 Running head: SPORTS VIDEO GAMES The Effects of Violence and Competition in Sports Video Games on Aggressive Thoughts, Feelings, and Physiological Arousal Kira Bailey Concord University Abstract Research over the past few decades has indicated that violent media, including video games, increase aggression (Anderson, 2004). The current study was investigating the effects that violent content and competitive scenarios in video games have on aggressive thought, feelings, and level of arousal in male college students. -

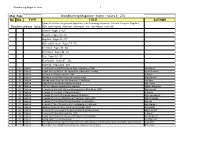

Woodturning Magazine Index 1

Woodturning Magazine Index 1 Mag Page Woodturning Magazine - Index - Issues 1 - 271 No. No. TYPE TITLE AUTHOR Types of articles are grouped together in the following sequence: Feature, Projects, Regulars, Readers please note: Skills and Projects, Technical, Technique, Test, Test Report, Tool Talk Feature - Pages 1 - 32 Projects - Pages 32 - 56 Regulars - Pages 56 - 57 Skills and Projects - Pages 57 - 70 Technical - Pages 70 - 84 Technique - Pages 84 - 91 Test - Pages 91 - 97 Test Report - Pages 97 - 101 Tool Talk - Pages 101 - 103 1 36 Feature A review of the AWGB's Hay on Wye exhibition in 1990 Bert Marsh 1 38 Feature A light hearted look at the equipment required for turning Frank Sharman 1 28 Feature A review of Raffan's work in 1990 In house 1 30 Feature Making a reasonable living from woodturning Reg Sherwin 1 19 Feature Making bowls from Norfolk Pine with a fine lustre Ron Kent 1 4 Feature Large laminated turned and carved work Ted Hunter 2 59 Feature The first Swedish woodturning seminar Anders Mattsson 2 49 Feature A report on the AAW 4th annual symposium, Gatlinburg, 1990 Dick Gerard 2 40 Feature A review of the work of Stephen Hogbin In house 2 52 Feature A review of the Craft Supplies seminar at Buxton John Haywood 2 2 31 Feature A review of the Irish Woodturners' Seminar, Sligo, 1990 Merryll Saylan 2 24 Feature A review of the Rufford Centre woodturning exhibition Ray Key 2 19 Feature A report of the 1990 instructors' conference in Caithness Reg Sherwin 2 60 Feature Melbourne Wood Show, Melbourne October 1990 Tom Darby 3 58 -

Tricky Dice a Game Design by Andy Miner Using Square Shooters Poker

Tricky Dice A game design by Andy Miner using Square Shooters Poker Dice Players: 4 Playing Time: about an hour Required Components: Standard deck of 52 playing cards (no jokers) One complete set of nine Square Shooters poker dice Bag/pouch to hold dice Pen and paper for scoring Order of Play 1. Before the Bid One player is chosen to be dealer. The dealer deals eight cards to every player. He then places all dice in the bag and passes it to his left. Each player in turn draws two dice from the bag and rolls them, placing them face up in front of him. After rolling his two dice, the dealer draws the last remaining dice from the bag and rolls it. The face-up side of this die will show the trump suit and highest card value for this hand. Note: If a player rolls a joker on his dice, he may turn the die to any other side that he wishes, after looking at his cards. However, it cannot be changed after that. Note: If the dealer rolls a joker space on the trump die, he may look at his cards and turn the die to one of the other five sides (his choosing) to determine the trump suit and high card for the hand. 2. The Bid Starting to the dealer’s left, each player may bid (or pass) on how many tricks they think they can take this hand with the help of a partner. The player on the dealer’s left must start with the minimum bid of four tricks, but may start higher. -

Valentine's Day

Dudley Hart REMINISCE leading at SUNDAY Vintage Valentines Pebble Beach ..........Page A-8 Feb. 10, 2008 ................................Page A-3 INSIDE Mendocino County’s World briefly The Ukiah local newspaper .......Page A-2 Monday: Mostly sunny; H 68º L 40º Tuesday: Sunshine, clouds; H 66º L 41º $1 tax included DAILY JOURNAL ukiahdailyjournal.com 44 pages, Volume 149 Number 307 email: [email protected] BOARD OF Local candy shop turning out SUPERVISORS Valentine’s Day: the chocolates Asphalt House of facility Burgess EIR on The bridge agenda By ROB BURGESS to nowhere The Daily Journal By ROB BURGESS A long-simmering debate The Daily Journal about the future of a local I’ve decided that I’m pretty quarry is likely set to once much the last person to know again boil over into impas- when it comes to most things. sioned rhetoric at Tuesday’s Before my coworker Sarah Mendocino County Board of told me about the documen- Supervisors meeting. tary “The Bridge,” I had no At 9:15 a.m., the board is idea the Golden Gate Bridge scheduled to introduce the was such a popular suicide Harris Quarry Draft destination. There have been Environmental Impact Report, more than 1,200 such deaths which will focus on both pub- there since it opened in 1937. lic and supervisor comments The film’s director, Eric on a proposed asphalt batch Steel, explored this phenome- plant on the site near Willits. non by recording almost two Several community groups, dozen of these leaps during including the Ridgewood Park the course of a year. -

White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents

Chess E-Magazine Interactive E-Magazine Volume 3 • Issue 1 January/February 2012 Chess Gambits Chess Gambits The Immortal Game Canada and Chess Anderssen- Vs. -Kieseritzky Bill Wall’s Top 10 Chess software programs C Seraphim Press White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents Editorial~ “My Move” 4 contents Feature~ Chess and Canada 5 Article~ Bill Wall’s Top 10 Software Programs 9 INTERACTIVE CONTENT ________________ Feature~ The Incomparable Kasparov 10 • Click on title in Table of Contents Article~ Chess Variants 17 to move directly to Unorthodox Chess Variations page. • Click on “White Feature~ Proof Games 21 Knight Review” on the top of each page to return to ARTICLE~ The Immortal Game 22 Table of Contents. Anderssen Vrs. Kieseritzky • Click on red type to continue to next page ARTICLE~ News Around the World 24 • Click on ads to go to their websites BOOK REVIEW~ Kasparov on Kasparov Pt. 1 25 • Click on email to Pt.One, 1973-1985 open up email program Feature~ Chess Gambits 26 • Click up URLs to go to websites. ANNOTATED GAME~ Bareev Vs. Kasparov 30 COMMENTARY~ “Ask Bill” 31 White Knight Review January/February 2012 White Knight Review January/February 2012 Feature My Move Editorial - Jerry Wall [email protected] Well it has been over a year now since we started this publication. It is not easy putting together a 32 page magazine on chess White Knight every couple of months but it certainly has been rewarding (maybe not so Review much financially but then that really never was Chess E-Magazine the goal). -

Games Ancient and Oriental and How to Play Them, Being the Games Of

CO CD CO GAMES ANCIENT AND ORIENTAL AND HOW TO PLAY THEM. BEING THE GAMES OF THE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS THE HIERA GRAMME OF THE GREEKS, THE LUDUS LATKUNCULOKUM OF THE ROMANS AND THE ORIENTAL GAMES OF CHESS, DRAUGHTS, BACKGAMMON AND MAGIC SQUAEES. EDWARD FALKENER. LONDON: LONGMANS, GEEEN AND Co. AND NEW YORK: 15, EAST 16"' STREET. 1892. All rights referred. CONTENTS. I. INTRODUCTION. PAGE, II. THE GAMES OF THE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS. 9 Dr. Birch's Researches on the games of Ancient Egypt III. Queen Hatasu's Draught-board and men, now in the British Museum 22 IV. The of or the of afterwards game Tau, game Robbers ; played and called by the same name, Ludus Latrunculorum, by the Romans - - 37 V. The of Senat still the modern and game ; played by Egyptians, called by them Seega 63 VI. The of Han The of the Bowl 83 game ; game VII. The of the Sacred the Hiera of the Greeks 91 game Way ; Gramme VIII. Tlie game of Atep; still played by Italians, and by them called Mora - 103 CHESS. IX. Chess Notation A new system of - - 116 X. Chaturanga. Indian Chess - 119 Alberuni's description of - 139 XI. Chinese Chess - - - 143 XII. Japanese Chess - - 155 XIII. Burmese Chess - - 177 XIV. Siamese Chess - 191 XV. Turkish Chess - 196 XVI. Tamerlane's Chess - - 197 XVII. Game of the Maharajah and the Sepoys - - 217 XVIII. Double Chess - 225 XIX. Chess Problems - - 229 DRAUGHTS. XX. Draughts .... 235 XX [. Polish Draughts - 236 XXI f. Turkish Draughts ..... 037 XXIII. }\'ci-K'i and Go . The Chinese and Japanese game of Enclosing 239 v. -

Heads and Tails Unit Overview

6 Heads and tails Unit Overview Outcomes READING In this unit pupils will: Pupils can: ●● Describe wild animals. ●● recognise cognates and deduce meaning of words in ●● Ask and answer about favourite animals. context. ●● Compare different animals’ bodies. ●● understand a poem, find specific information and transfer ●● Write about a wild animal. this to a table. ●● read and complete a gapped text about two animals. Productive Language WRITING VOCABULARY Pupils can: ●● Animals: a crocodile, an elephant, a giraffe, a hippo, ●● write short descriptive texts following a model. a monkey, an ostrich, a pony, a snake. Strategies ●● Body parts: an arm, fingers, a foot, a head, a leg, a mouth, a nose, a tail, teeth, toes, wings. Listen for words that are similar in other languages. L 1 ●● Adjectives: fat, funny, hot, long, short, silly, tall. PB p.35 ex2 PHRASES Before you listen, look at the pictures and guess. ●● It has got/It hasn’t got (a long neck). L 2 AB p.39 ex5 ●● Has it got legs? Yes, it has./No, it hasn’t. Read the questions before you listen. Receptive Language L 3 PB p.39 ex1 VOCABULARY Listen and try to understand the main idea. ●● Animals: butterfly, meerkat, penguin, whale. L 4 ●● Africa, apple, beak, carrot, lake, water, wildlife park. PB p.36 ex1 ●● Eat, live, fly. S Use the model to help you speak. PHRASES 3 PB p.38 ex2 ●● It lives ... Look for words that are similar in other languages. R 2 Recycled Language AB p.38 ex1 VOCABULARY Use your Picture Dictionary to help you spell. -

ON the MARKET for First Win Brings People Guide to Local Real Estate at Eureka Together for Peace

Wildcats try Earthdance ON THE MARKET for first win brings people Guide to local real estate at Eureka together for peace ..........Page A-6 ...............Page A-3 ...................................Inside INSIDE Mendocino County’s World briefly The Ukiah local newspaper .......Page A-2 Tomorrow: Sunny and warm 7 58551 69301 0 FRIDAY Sept. 22, 2006 50 cents tax included DAILY JOURNAL ukiahdailyjournal.com 44 pages, Volume 148 Number 166 email: [email protected] CITY OF UKIAH ‘We’ve lost a good friend in the passing of Norm Vroman. He was a wonderful guy.’ – Former Sheriff TONY CRAVER Police aim to recruit DA Vroman dies officers via Vroman By BEN BROWN ‘It is with deep regret and television The Daily Journal District Attorney Norman sorrow that I have to inform By BEN BROWN Vroman died Thursday The Daily Journal afternoon at a Santa Rosa the people of Mendocino Starting next week, the Ukiah hospital of complications Police Department will be using a due to a heart attack. County that District Attorney new tool in its effort to recruit The 69-year-old Vroman Norman L. Vroman passed qualified applicants onto the force: was rushed to Sutter Valley television. Memorial Hospital by heli- away this afternoon, “The ultimate idea is to get peo- copter Tuesday morning, ple talking about it and considering after suffering a heart attack Thursday, Sept. 21, 2006.’ a career in law enforcement,” said at his home. UPD Capt. Chris Dewey. His condition was KEITH FAULDER The commercial will air on five described as critical by hos- assistant district attorney, cable stations during a two-week pital staff on Tuesday when in an announcement Thursday from period. -

Stanislaus County Elementary Spelling Championship

Stanislaus County Elementary Spelling Championship Word List (Same book for past years - no revisions were made) Note: as indicated in the Stanislaus County Spelling Championship Rules (available on the following website: www.scoestudentevents.org) “Words are chosen from multiple sources” in addition to this word list. 1 abbreviate - uh-BREE-vee-ayt shorten In formal papers, it is not proper to abbreviate words. ____________________________________________________ abdominal - ab-däm-n’l lower part of the truck of the human body; in, or for the abdomen The abdominal bandage seemed too tight. ____________________________________________________ abhor - ab HOR to shrink from in fear; detest I abhor baiting my fishhook with worms. ____________________________________________________ absurd - AB-surd so clearly untrue or unreasonable as to be ridiculous It was absurd to say the baby could reach the counter. ____________________________________________________ accessory - ak SES uh ree useful but not essential thing That necklace is a nice accessory to your outfit. ____________________________________________________ accommodate - a-kä-ma-DATE to make fit, suitable, or congruous The school can now accommodate handicapped students. ____________________________________________________ acoustics - uh KOOHS tiks the qualities of a room that enhance or deaden sound The concert hall is known for its fine acoustics. ____________________________________________________ active - AK tiv lively, busy, agile Last night I baby-sat for a very active two-year old. ____________________________________________________ acumen - a-ku-men acuteness of mind; keenness in intellectual or practical matters He was a businessman of acknowledged acumen. ____________________________________________________ addendum - a-den-dum thing added or to be added The name of the second speaker is an addendum to the program. ____________________________________________________ addressee - a-dre-sE OR u-dre-sE person to whom mail, etc., is addressed His name is that of the addressee on the envelope. -

Cognitive Psychology

COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY PSYCH 126 Acknowledgements College of the Canyons would like to extend appreciation to the following people and organizations for allowing this textbook to be created: California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office Chancellor Diane Van Hook Santa Clarita Community College District College of the Canyons Distance Learning Office In providing content for this textbook, the following professionals were invaluable: Mehgan Andrade, who was the major contributor and compiler of this work and Neil Walker, without whose help the book could not have been completed. Special Thank You to Trudi Radtke for editing, formatting, readability, and aesthetics. The contents of this textbook were developed under the Title V grant from the Department of Education (Award #P031S140092). However, those contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. Unless otherwise noted, the content in this textbook is licensed under CC BY 4.0 Table of Contents Psychology .................................................................................................................................................... 1 126 ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Chapter 1 - History of Cognitive Psychology ............................................................................................. 7 Definition of Cognitive Psychology -

Probability and Counting Rules

blu03683_ch04.qxd 09/12/2005 12:45 PM Page 171 C HAPTER 44 Probability and Counting Rules Objectives Outline After completing this chapter, you should be able to 4–1 Introduction 1 Determine sample spaces and find the probability of an event, using classical 4–2 Sample Spaces and Probability probability or empirical probability. 4–3 The Addition Rules for Probability 2 Find the probability of compound events, using the addition rules. 4–4 The Multiplication Rules and Conditional 3 Find the probability of compound events, Probability using the multiplication rules. 4–5 Counting Rules 4 Find the conditional probability of an event. 5 Find the total number of outcomes in a 4–6 Probability and Counting Rules sequence of events, using the fundamental counting rule. 4–7 Summary 6 Find the number of ways that r objects can be selected from n objects, using the permutation rule. 7 Find the number of ways that r objects can be selected from n objects without regard to order, using the combination rule. 8 Find the probability of an event, using the counting rules. 4–1 blu03683_ch04.qxd 09/12/2005 12:45 PM Page 172 172 Chapter 4 Probability and Counting Rules Statistics Would You Bet Your Life? Today Humans not only bet money when they gamble, but also bet their lives by engaging in unhealthy activities such as smoking, drinking, using drugs, and exceeding the speed limit when driving. Many people don’t care about the risks involved in these activities since they do not understand the concepts of probability. -

Temporal Difference Learning Algorithms Have Been Used Successfully to Train Neural Networks to Play Backgammon at Human Expert Level

USING TEMPORAL DIFFERENCE LEARNING TO TRAIN PLAYERS OF NONDETERMINISTIC BOARD GAMES by GLENN F. MATTHEWS (Under the direction of Khaled Rasheed) ABSTRACT Temporal difference learning algorithms have been used successfully to train neural networks to play backgammon at human expert level. This approach has subsequently been applied to deter- ministic games such as chess and Go with little success, but few have attempted to apply it to other nondeterministic games. We use temporal difference learning to train neural networks for four such games: backgammon, hypergammon, pachisi, and Parcheesi. We investigate the influ- ence of two training variables on these networks: the source of training data (learner-versus-self or learner-versus-other game play) and its structure (a simple encoding of the board layout, a set of derived board features, or a combination of both of these). We show that this approach is viable for all four games, that self-play can provide effective training data, and that the combination of raw and derived features allows for the development of stronger players. INDEX WORDS: Temporal difference learning, Board games, Neural networks, Machine learning, Backgammon, Parcheesi, Pachisi, Hypergammon, Hyper-backgammon, Learning environments, Board representations, Truncated unary encoding, Derived features, Smart features USING TEMPORAL DIFFERENCE LEARNING TO TRAIN PLAYERS OF NONDETERMINISTIC BOARD GAMES by GLENN F. MATTHEWS B.S., Georgia Institute of Technology, 2004 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE ATHENS,GEORGIA 2006 © 2006 Glenn F. Matthews All Rights Reserved USING TEMPORAL DIFFERENCE LEARNING TO TRAIN PLAYERS OF NONDETERMINISTIC BOARD GAMES by GLENN F.