The Victoria Institute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Golgotha and the Holy Sepulchre," Which Sir C

109 'vjOLGOTHA AND THE Holy Sepulchre BY THE LATE MAJOR GENERAL SIR C.W.WILSON K.CB., Etc, Etc., Etc. CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/cletails/cu31924028590499 """"'"'" '""'"' DS 109.4:W74 3 1924 028 590 499 COINS OF ROMAN EMPERORS. GOLGOTHA AND THE HOLY SEPULCHRE BY THE LATE MAJOR-GENERAL SIR C. W. WILSON, R.E., K.C.B., K.C.M.G., F.R.S., D.C.L., LL.D. EDITED BY COLONEL SIR C. M. WATSON, R.E., K.C.M.G., C.B., M.A. f,-f (».( Published by THE COMMITTEE OF THE PALESTINE EXPLORATION FUND, 38, Conduit Street, London, W. igo6 All rights reserved. HAKKISON AKD SOSS, PIUSTEH5 IN OBMNAEY 10 HIS MAJliSTV, ST MAHTIX'S LAK'li, LOSDOiV, W.C. CONTENTS. PAGE Introductory Note vii CHAPTEE I. Golgotha—The Name ... 1 CHAPTEE II. Was there a Public Place op Execution at Jerusalem in THE Time of Christ? 18 CHAPTER III. The Topography of Jerusalem at the Time op the Crucifixion 24 CHAPTER IV. The Position of Golgotha—The Bible Narrative 30 CHAPTER V. On the Position op certain Places mentioned in the Bible Narrative—Gethsemane—The House of Caiaptias —The Hall op the Sanhedein—The Pr^torium ... 37 CHAPTEE VI. The Arguments in Favour op the Authenticity of the Traditional Sites 45 CHAPTER VII. The History op Jerusalem, a.d. 33-326 49 Note on the Coins of JElia 69 CHAPTEE VIII. -

Middle Miocene Paleoenvironmental Reconstruction of the Central Great Plains from Stable Carbon Isotopes in Large Mammals Willow H

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations & Theses in Earth and Atmospheric Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department of Sciences 7-2017 Middle Miocene Paleoenvironmental Reconstruction of the Central Great Plains from Stable Carbon Isotopes in Large Mammals Willow H. Nguy University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geoscidiss Part of the Geology Commons, Paleobiology Commons, and the Paleontology Commons Nguy, Willow H., "Middle Miocene Paleoenvironmental Reconstruction of the Central Great Plains from Stable Carbon Isotopes in Large Mammals" (2017). Dissertations & Theses in Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. 91. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geoscidiss/91 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations & Theses in Earth and Atmospheric Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. MIDDLE MIOCENE PALEOENVIRONMENTAL RECONSTRUCTION OF THE CENTRAL GREAT PLAINS FROM STABLE CARBON ISOTOPES IN LARGE MAMMALS by Willow H. Nguy A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Major: Earth and Atmospheric Sciences Under the Supervision of Professor Ross Secord Lincoln, Nebraska July, 2017 MIDDLE MIOCENE PALEOENVIRONMENTAL RECONSTRUCTION OF THE CENTRAL GREAT PLAINS FROM STABLE CARBON ISOTOPES IN LARGE MAMMALS Willow H. Nguy, M.S. University of Nebraska, 2017 Advisor: Ross Secord Middle Miocene (18-12 Mya) mammalian faunas of the North American Great Plains contained a much higher diversity of apparent browsers than any modern biome. -

Morton County, Kansas Michael Anthony Calvello Fort Hays State University

Fort Hays State University FHSU Scholars Repository Master's Theses Graduate School Summer 2011 Mammalian Fauna From The ulF lerton Gravel Pit (Ogallala Group, Late Miocene), Morton County, Kansas Michael Anthony Calvello Fort Hays State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.fhsu.edu/theses Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Calvello, Michael Anthony, "Mammalian Fauna From The ulF lerton Gravel Pit (Ogallala Group, Late Miocene), Morton County, Kansas" (2011). Master's Theses. 135. https://scholars.fhsu.edu/theses/135 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at FHSU Scholars Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of FHSU Scholars Repository. - MAMMALIAN FAUNA FROM THE FULLERTON GRAVEL PIT (OGALLALA GROUP, LATE MIOCENE), MORTON COUNTY, KANSAS being A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the Fort Hays State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science by Michael Anthony Calvello B.A., State University of New York at Geneseo Date Z !J ~4r u I( Approved----c-~------------- Chair, Graduate Council Graduate Committee Approval The Graduate Committee of Michael A. Calvello hereby approves his thesis as meeting partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Degree of Master of Science. Approved: )<--+-- ----+-G~IJCommittee Meilnber Approved: ~J, iii,,~ Committee Member 11 ABSTRACT The Fullerton Gravel Pit, Morton County, Kansas is one of many sites in western Kansas at which the Ogallala Group crops out. The Ogallala Group was deposited primarily by streams flowing from the Rocky Mountains. Evidence of water transport is observable at the Fullerton Gravel Pit through the presence of allochthonous clasts, cross-bedding, pebble alignment, and fossil breakage and subsequent rounding. -

The Flaxville Gravel and ·Its Relation to Other Terrace Gravels of the Northern Great Plains

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRANKLIN K. LANE, Secretary . -UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, Director Professional Paper 108-J THE FLAXVILLE GRAVEL AND ·ITS RELATION TO OTHER TERRACE GRAVELS OF THE NORTHERN GREAT PLAINS BY ARTHUR J. COLLIER AND W. T. THOM, JR. Published January 26,1918 Shorter contributions to general geology, 1917 ( Paates 179-184 ) WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1918 i, '!· CONTENTS. Page. Introduction ............... ~ ... ~ ........... , ........... .......... ~ ......................... ~ .... -.----- 179 Flaxville gravel ......................................................................· .. ............ ·.... 179 Late Pliocene or early Pleistocene gravel. ..................................... ..... .. .................• - 182 Late Pleistocene and Recent erosion and deposition ........................ ..... ............ ~ ............ 182 Oligocene beds in Cypress Hilla .................... .' ................. ........................ .......... 183 Summary ....•......................... ················· · ·· · ·········.···············"···················· 183 ILLUSTRA 'fl ONS. Page. PLATE LXII. Map of northeastern Montana and adjacent parts of Canada, showing the distribution of erosion levels and gravel horizons................................................................ 180 J,XIII. A, Surface of the Flaxville plateau, northeastern Montana; B, Outcrop of cemented Flaxville gravel in escarpment ·of plateau northwest of Opheim, Mont.; C; Escarpment of the Flaxville plateau, northeastern -

Aelia Capitolina’ Through a Review of the Archaeological Data

Roman changes to the hill of Gareb in ‘Aelia Capitolina’ through a review of the archaeological data Roberto Sabelli Dipartimento di Architettura Università degli Studi di Firenze Abstract opposite page Following Jewish revolts, in 114-117 and 132-136 AD, the colony of Iulia Aelia Cap- Fig.1 itolina was founded by Publio Elio Traiano Adriano on the site of Jerusalem – View of the east side Aelia in his honour and Capitolina because it was intended to contain a Capi- of the old walled city from Kidron Valley tol for the Romans – so as to erase Jewish and Christian memories. On the ba- (R. Sabelli 2007) sis of the most recent research it is possible to reconstruct the main phases of transformation by the Romans of a part of the hill of Gareb: from a stone quar- ry (tenth century BC - first century AD) into a place of worship, first pagan with the Hadrianian Temple (second century AD) then Christian with the Costantin- ian Basilica (fourth century AD). Thanks to the material evidence, historical tes- timonies, and information on the architecture of temples in the Hadrianic pe- riod, we attempt to provide a reconstruction of the area where the pagan tem- ple was built, inside the expansion of the Roman town in the second century AD, aimed at the conservation and enhancement of these important traces of the history of Jerusalem. 1 The Gehenna Valley (Wadi er-Rababi to- The hill of Gareb in Jerusalem to the north of Mount Zion, bounded on the day) was for centuries used as city ity 1 dump and for disposing of the unburied south and west by the Valley of Gehenna (Hinnom Valley) , rises to 770 me- corpses of delinquents, which were then ters above sea level; its lowest point is at its junction with the Kidron Valley, burned. -

Giant Camels from the Cenozoic of North America SERIES PUBLICATIONS of the SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION

Giant Camels from the Cenozoic of North America SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to the H^arine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Folklife Studies Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that refXJrt the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world of science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the worid. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given substantive review. Press requirements for manuscript and art preparation are outlined on the inside back cover. -

Multivariate Discriminant Function Analysis of Camelid Astragali

Palaeontologia Electronica palaeo-electronica.org A method for improved identification of postcrania from mammalian fossil assemblages: multivariate discriminant function analysis of camelid astragali Edward Byrd Davis and Brianna K. McHorse ABSTRACT Character-rich craniodental specimens are often the best material for identifying mammalian fossils to the genus or species level, but what can be done with the many assemblages that consist primarily of dissociated postcrania? In localities lacking typi- cally diagnostic remains, accurate identification of postcranial material can improve measures of mammalian diversity for wider-scale studies. Astragali, in particular, are often well-preserved and have been shown to have diagnostic utility in artiodactyls. The Thousand Creek fauna of Nevada (~8 Ma) represents one such assemblage rich in postcranial material but with unknown diversity of many taxa, including camelids. We use discriminant function analysis (DFA) of eight linear measurements on the astragali of contemporaneous camelids with known taxonomic affinity to produce a training set that can then be used to assign taxa to the Thousand Creek camelid material. The dis- criminant function identifies, at minimum, four classes of camels: “Hemiauchenia”, Alforjas, Procamelus, and ?Megatylopus. Adding more specimens to the training set may improve certainty and accuracy for future work, including identification of camelids in other faunas of similar age. For best statistical practice and ease of future use, we recommend using DFA rather than qualitative analyses of biplots to separate and diag- nose taxa. Edward Byrd Davis. University of Oregon Museum of Natural and Cultural History and Department of Geological Sciences, 1680 East 15th Avenue, Eugene, Oregon 97403. [email protected] Brianna K. -

Description and CT Scan Henry Kirkland, Jr

63 A Complete Tertiary Camel Skull from Roger Mills County: Description and CT Scan Henry Kirkland, Jr. Department of Biological Sciences, Southwestern Oklahoma State University, Weatherford, OK 73096 Received: 1992 Dec 18; Revised: 1993 Aug 02 The Tertiary beds exposed in Roger Mills County are continuous with beds which cover the northeastern part of the Texas panhandle; they are the Ogallala formation (1). The Ogallala rocks in northern Roger Mills County rest unconformably upon the Permian Cloud Chief and Quartermasters formations. The Ogallala rocks consist of fine to medium grain, well-sorted quartz sand and are about 90 m thick. At places where the lower 63 m of Ogallala section are exposed, the rocks are predominantly yellowish-brown, evenly bedded fine-grained quartz sands (1). Figure 1. Complete skull of Procamelus cf A complete camel skull with several articulated grandis with articulated cervical vertebrae. vertebrae was found in the Fall of 1991 at Section 3, T15N R23W, in northwestern Roger Mills County. The excavated, late Miocene, camel skull was in good condition with several cervical vertebrae attached. The skull was completely encased within the Ogallala formation (Fig. 1). The camel skull was identified, by comparison with the fossil collection at Southwestern Oklahoma State University, as Procamelus cf grandis (2). Procamelus, described by Leidy (1858), has long functioned as a catchall genus for medium- to Figure 2. Right side of intact skull: (a) the eye socket; (b) a protruding metacarpal. large-sized Pliocene-age camelids (3). This skull is the third Tertiary Procamelus found in Oklahoma. Previous finds, in 1989 and 1990, were identified by comparison with fossil camels at the Natural History Museum, University of Kansas (2). -

Carcharodon Megalodon in a Time Capsule

Inside The Newsletter of the - Highlights Calvert Marine Museum • Bowhead Support Services • Reinecke's Gomphothere Art Fossil Club Sponsors New Whale Exhibit • Gomphotherium calvertensis Volume 19 • Number 2 The Margaret Clark Smith • Upcoming Field Trips Collection on Display July 2004 Whole Number 63 • Miocene Rhino tooth from Calvert Cliffs The Carcharodon megalodon in a Bowhead Support Services, an Alaska Time Capsule Native Corporation (www.Bowhead.com). deriving its name from the Bowhead Whale, has partnered As part of Calvert County's 350th with the Calvert Marine Museum to sponsor a new Anniversary celebrations, a time capsule was just exhibit on the fossil baleen whale found by Jeff buried in the Courthouse to be opened 100 years DiMeglio last year after Hurricane Isabel. Their two from now. I suggested they include a Carcharodon year sponsorship will fund the preparation of the megalodon tooth, with which they agreed. Chris O. skull as well as the development of an exhibit on this Donaldson donated the tooth that was "reburied," to .J.<..:velyspecimen. Our sincerest thanks go out to the Museum in 1998. He found it by flashlight early Jwhead for their interest in furthering our one morning in 1998 as float along Scientists Cliffs. understanding of the history and diversity of Pat Fink catalogued the tooth, giving it CMM- V-10, prehistoric whales! V 000 (highest vertebrate number now is CMM -V• 2400) with the expectation that the tooth will be Former Calvert Marine Museum Director returned to our permanent collections in 100 years and Vertebrate Paleontologist, Dr. Ralph Eshelman (at which time I'll throw a really big party f9r has added numerous valuable and important surviving members of the fossil club). -

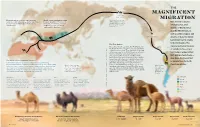

Magnificent Migration

THE MAGNIFICENT Land bridge 8 MY–14,500 Y MIGRATION Domestication of camels began between World camel population today About 6 million years ago, 3,000 and 4,000 years ago—slightly later than is about 30 million: 27 million of camelids began to move Best known today for horses—in both the Arabian Peninsula and these are dromedaries; 3 million westward across the land Camelini western Asia. are Bactrians; and only about that connected Asia and inhabiting hot, arid North America. 1,000 are Wild Bactrians. regions of North Africa and the Middle East, as well as colder steppes and Camelid ancestors deserts of Asia, the family Camelidae had its origins in North America. The The First Camels signature physical features The earliest-known camelids, the Protylopus and Lamini E the Poebrotherium, ranged in sizes comparable to of camels today—one or modern hares to goats. They appeared roughly 40 DMOR I SK million years ago in the North American savannah. two humps, wide padded U L Over the 20 million years that followed, more U L ; feet, well-protected eyes— O than a dozen other ancestral members of the T T O family Camelidae grew, developing larger bodies, . E may have developed K longer legs and long necks to better browse high C I The World's Most Adaptable Traveler? R ; vegetation. Some, like Megacamelus, grew even I as adaptations to North Camels have adapted to some of the Earth’s most demanding taller than the woolly mammoths in their time. LEWSK (Later, in the Middle East, the Syrian camel may American winters. -

Itinerary Women's Mission 2020

ITINERARY WOMEN'S MISSION 2020 fidf.org/missions • [email protected] • 1888-318-3433 ITINERARY THURSDAY, DAY 1: WELCOME TO ISRAEL! • Arrive independently and check in at the King David Hotel in Jerusalem • Official commencement of FIDF’s National Women’s Mission, led by Brigadier General (Res.) Gila Klifi-Amir • 07:00 pm Welcome dinner and ice-breaker activity OVERNIGHT: KING DAVID HOTEL, 23 KING DAVID ST., JERUSALEM +972-2-620-8888 FRIDAY, DAY 2: • Breakfast at the hotel • Hear from a high-ranking officer about the current sociopolitical climate in Israel • Visit the Kotel tunnels and Zedekiah's Cave - a 5-acre underground meleke limestone quarry that runs the length of five city blocks under the Muslim Quarter of theOld City of Jerusalem • Visit the President's house to honor Nechama Rivlin z'l and her work on behalf of women, art for kids with disabilities, and the environment • Enjoy a festive Shabbat dinner, exclusively for mission participants, at the stunning home of Aba and Pamela Claman in the Old City OVERNIGHT: KING DAVID HOTEL fidf.org/missions • [email protected] • 1888-318-3433 1 ITINERARY SATURDAY, DAY 3: • Breakfast at the hotel • Experience Jerusalem’s rich history through a walking tour of Jerusalem’s historic Old City with an emphasis Christian and Jewish history • Dinner and lecture at the hotel by Dvorah Forum, a professional network of senior women in foreign policy, security, public policy, and law who aim to advance the standing of women in the IDF • Depart for dinner and special evening out in Jerusalem OVERNIGHT: KING DAVID HOTEL SUNDAY, DAY 4: • Breakfast at the hotel • Check out from the hotel • Visit the Hall of Remembrance for Fallen Soldiers on Mount Herzl • Drive to Sde Boker fidf.org/missions • [email protected] • 1888-318-3433 2 ITINERARY • Visit to Masu'ot Yitzhak, a pre-military academy for religious girls, named after Tamar Ariel z”l, the first religious female navigator in the IAF. -

Description of a Fossil Camelid from the Pleistocene of Argentina, and a Cladistic Analysis of the Camelinae

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2020 Description of a fossil camelid from the Pleistocene of Argentina, and a cladistic analysis of the Camelinae Lynch, Sinéad ; Sánchez-Villagra, Marcelo R ; Balcarcel, Ana Abstract: We describe a well-preserved South American Lamini partial skeleton (PIMUZ A/V 4165) from the Ensenadan ( 1.95–1.77 to 0.4 Mya) of Argentina. The specimen is comprised of a nearly complete skull and mandible with full tooth rows, multiple elements of anterior and posterior limbs, and a scapula. We tested this specimen’s phylogenetic position and hypothesized it to be more closely related to Lama guanicoe and Vicugna vicugna than to Hemiauchenia paradoxa. We formulate a hypothesis for the placement of PIMUZ A/V 4165 within Camelinae in a cladistic analysis based on craniomandibular and dental characters and propose that future systematic studies consider this specimen as representing a new species. For the first time in a morphological phylogeny, we code terminal taxa at the species levelfor the following genera: Camelops, Aepycamelus, Pleiolama, Procamelus, and Alforjas. Our results indicate a divergence between Lamini and Camelini predating the Barstovian (16 Mya). Camelops appears as monophyletic within the Camelini. Alforjas taylori falls out as a basal member of Camelinae—neither as a Lamini nor Camelini. Pleiolama is polyphyletic, with Pleiolama vera as a basal Lamini and Pleiolama mckennai in a more nested position within the Lamini. Aepycamelus and Procamelus are respectively polyphyletic and paraphyletic. Together, they are part of a group of North American Lamini from the Miocene epoch.