STABILIZATION and DEMOCRATIZATION of IRAQ a STRATEGIC ANALYSIS of the CONSTITUTION-BUILDING PROCESS a Thesis Presented To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

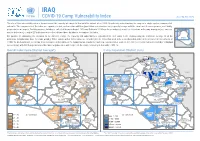

COVID-19 Camp Vulnerability Index As of 04 May 2020

IRAQ COVID-19 Camp Vulnerability Index As of 04 May 2020 The aim of this vulnerability index is to understand the capacity of camps to deal with the impact of a COVID-19 outbreak, understanding the camp as a single system composed of sub-units. The components of the index are: exposure to risk, system vulnerabilities (population and infrastructure), capacity to cope with the event and its consequences, and finally, preparedness measures. For this purpose, databases collected between August 2019 and February 2020 have been analysed, as well as interviews with camp managers (see sources next to indicators), a total of 27 indicators were selected from those databases to compose the index. For purpose of comparing the situation on the different camps, the capacity and vulnerability is calculated for each camp in the country using the arithmetic average of all the IRAQ indicators (all indicators have the same weight). Those camps with a higher value are considered to be those that need to be strengthened in order to be prepared for an outbreak of COVID-19. Each indicator, according to its relevance and relation to the humanitarian standards, has been evaluated on a scale of 0 to 100 (see list of indicators and their individual assessment), with 100 being considered the most negative value with respect to the camp's capacity to deal with COVID-19. Overall Index Score (District Average*) Camp Population (District Sum) TURKEY TURKEY Zakho Zakho Al-Amadiya 46,362 Al-Amadiya 32 26 3,205 DUHOK Sumail DUHOK Sumail Al-Shikhan 83,965 Al-Shikhan Aqra -

Rebooting U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq

Rebooting U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq MICHAEL KNIGHTS POLICY FOCUS 137 Rebooting U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq MICHAEL KNIGHTS THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY www.washingtoninstitute.org The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessarily those of The Washington Institute, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2015 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050 Washington, DC 20036 Design: 1000colors Photo: A Kurdish fighter keeps guard while overlooking positions of Islamic State mili- tants near Mosul, northern Iraq, August 2014. (REUTERS/Youssef Boudlal) CONTENTS Acknowledgments | v Acronyms | vi Executive Summary | viii 1 Introduction | 1 2 Federal Government Security Forces in Iraq | 6 3 Security Forces in Iraqi Kurdistan | 26 4 Optimizing U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq | 39 5 Issues and Options for U.S. Policymakers | 48 About the Author | 74 TABLES 1 Effective Combat Manpower of Iraq Security Forces | 8 2 Assessment of ISF and Kurdish Forces as Security Cooperation Partners | 43 FIGURES 1 ISF Brigade Order of Battle, January 2015 | 10 2 Kurdish Brigade Order of Battle, January 2015 | 28 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My thanks to a range of colleagues for their encouragement and assistance in the writing of this study. -

IRAQ COUNTRY REPORT April 2004 COUNTRY INFORMATION

IRAQ COUNTRY REPORT April 2004 COUNTRY INFORMATION & POLICY UNIT IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM CONTENTS 1 Scope of document 1.1 – 1.7 2 Geography 2.1 – 2.6 3 Economy 3.1 – 3.3 4 History Post Saddam Iraq 4.3 – 4.11 History of northern Iraq 4.12 – 4.15 5 State Structures The Constitution 5.1 – 5.2 The Transitional Administrative Law 5.3 – 5.5 Nationality and Citizenship 5.6 Political System 5.7 –5.14 Interim Governing Council 5.7 – 5.8 Cabinet 5.9 – 5.11 Northern Iraq 5.12 – 5.14 Judiciary 5.15 – 5.27 Judiciary in northern Iraq 5.28 Justice for human rights abusers 5.29 – 5.31 Legal Rights/Detention 5.32 – 5.38 Death penalty 5.34 Torture 5.35 – 5.38 Internal Security 5.39 – 5.52 Police 5.41 – 5.46 Security services 5.47 Militias 5.48 – 5.52 Prisons and prison conditions 5.53 – 5.59 Military Service 5.60 – 5.61 Medical Services 5.62 – 5.79 Mental health care 5.71 – 5.74 HIV/AIDS 5.75 – 5.76 People with disabilities 5.77 Educational System 5.78 – 5.79 6 Human Rights 6A Human Rights issues Security situation 6.4 – 6.14 Humanitarian situation 6.15 – 6.22 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.23 – 6.28 Freedom of Religion 6.29 – 6.47 Shi’a Muslims 6.31 Sunni Muslims 6.32 Christians 6.33 – 6.38 Mandaeans 6.39 Yazidis 6.40 – 6.45 Jews 6.46 – 6.47 Freedom of Association and Assembly 6.48 Employment Rights 6.49 People Trafficking 6.50 Freedom of Movement 6.51 – 6.54 Internal travel 6.51 – 6.53 Travel to Iraq 6.54 6B Human rights - Specific Groups Ethnic Groups 6.55 – 6.74 Shi’a Arabs 6.55 – 6.60 Sunni Arabs 6.61 – -

Constitution of 'Iraq

[Distributed to the Official No. : C. 49. 1929. VI. Members of the Council.] [C.P.M.834] Geneva, February 20th, 1929. LEAGUE OF NATIONS CONSTITUTION OF ‘IRAQ (ORGANIC LAW) Note by the Secretary- General : The Secretary-General communicated to the Council, on August 23rd, 1924 (document C.412.1924.VI, C.P.M. 166),1 a letter from the British Government transmitting a translation of the Organic Law of ‘Iraq passed by the Constituent Assembly of ‘Iraq on July 10th, 1924. In a letter dated November 28th, 1928, the British Government transmitted the following document : The ‘Iraq Constitution, March 21st, 1925, recently published by the Government of ‘Iraq. The British Government points out, in the above-mentioned letter, that the publication of the document in question was necessitated by the discovery of considerable discrepancies between the Arabic text of the Organic Law, as passed by the ‘Iraq Constituent Assembly in July 1924, and the English translation which was communicated to the Secretariat in 1924. The British Government adds that the new text embodies the modifications introduced by the Organic Law Amendment Law, 1925,2 and was approved by the ‘Iraq Government as superseding all translations of the law hitherto published. The Secretary-General has the honour to communicate to the Council the text of the document transmitted by the British Government on November 28th, 1928. 1 See Official Journal, November 1924, page 1759. * The Organic Law Amendment Law, 1925, was published as an Appendix to the Annual Report on the Adminis tration of ‘Iraq for 1925, pages 175-177. S.d.N. -

Official General Report on Northern Iraq (April 2000) Contents Page

Official general report on Northern Iraq (April 2000) Contents Page 1. Introduction 4 2. Information on the country 6 2.1. Basic facts 6 2.1.1. Country and people 6 2.1.2. History 8 2.2. System of government 17 2.3. Political developments 20 2.3.1. Internal relations 20 2.3.2. External forces 31 2.4. Security situation 36 2.5. Social and economic situation 48 2.6. Conclusions 53 3. Human rights 55 3.1. Safeguards 55 3.1.1. Constitution 55 3.1.2. Other national legislation 55 3.1.3. Conventions 56 3.2. Monitoring 56 3.3. Respect and violations 58 3.3.1. Freedom of opinion 58 3.3.2. Freedom of association and of assembly 59 3.3.3. Freedom of religion 60 3.3.4. Freedom of movement 73 3.3.5. Judicial process 83 3.3.6. Arrest and detention 84 3.3.7. Maltreatment and torture 87 3.3.8. Extra-judicial executions and murders 87 10804/00 dre/LG/mc 2 DG H I EN 3.3.9. Death penalty 87 3.4. Position of specific groups 88 3.4.1. Turkmens 88 3.4.2. Staff of international organisations 91 3.4.3. Conscripts, deserters and servicemen 96 3.4.4. Independent intellectuals and journalists 98 3.4.5. Prominent political activists 99 3.4.6. Fayli Kurds 99 3.4.7. Women 101 3.4.8. Orphaned minors 104 3.5. Summary 104 4. Refugees and displaced persons 106 4.1. Motives 106 4.2. -

Gender Equality Discourse in Yemini Constitutions

GENDER EQUALITY DISCOURSE IN YEMINI CONSTITUTIONS RIGHTS AND DUTIES AMAL AL BASHA NO. 2014/3 Authors: Amal Al Basha The lines engraved on this paper are a humble effort dedicated to: All my country’s girls, young girls, young women as well as worn out, poor and distressed women in both rural and urban communities, in each corner of this country, dreaming of the dawn of equality, justice and equity to break soon, and it is indeed soon. © 2014 The Danish Institute for Human Rights Denmark’s National Human Rights Institution Wilders Plads 8K DK-1403 Copenhagen K Phone +45 3269 8888 www.humanrights.dk This publication, or parts of it, may be reproduced if author and source are quoted. MATTERS OF CONCERN is a working paper series focusing on new and emerging research on human rights across academic disciplines. It is a means for DIHR staff, visiting fellows and external researchers to make available the preliminary results of their research, work in progress and unique research contributions. Research papers are published under the responsibility of the author alone and do not represent the official view of the Danish Institute of Human Rights. Papers are available online at www.humanrights.dk. CONTENT INTRODUCTION 8 The importance of this research paper 9 The research methodology 11 1 EQUALITY AND DISCRIMINATION IN THE CONSTITUTIONS OF YEMEN IN THE SOUTH 12 1.1 The British Occupation Stage 12 1.1.1 The Laws of the Colony of Aden 12 1.1.2 The Constitution of the Colony of Aden, 1962 13 1.1.3 The Constitutions of the Sultanates, Emirates and -

IRAQ: Humanitarian Operational Presence (3W) for HRP and Non-HRP Activities January to June 2021

IRAQ: Humanitarian Operational Presence (3W) for HRP and Non-HRP Activities January to June 2021 TURKEY 26 Zakho Number of partners by cluster DUHOK Al-Amadiya 11 3 Sumail Duhok 17 27 33 Rawanduz Al-Shikhan Aqra Telafar 18 ERBIL 40 Tilkaef 4 23 8 Sinjar Shaqlawa 57 4 Pshdar Al-Hamdaniya Al-Mosul 4 Rania 1 NINEWA 37 Erbil Koysinjaq 23 Dokan 1 Makhmour 2 Al-Baaj 15 Sharbazher 16 Dibis 9 24 Al-Hatra 20 Al-Shirqat KIRKUK Kirkuk Al-Sulaymaniyah 15 6 SYRIA Al-Hawiga Chamchamal 21 Halabcha 18 19 6 2 Daquq Beygee 16 12 Tooz Kalar Tikrit Khurmato 12 8 2 11 SALAH AL-DIN Kifri Al-Daur Ana 2 6 Al-Kaim 7 Samarra 15 13 Haditha Al-Khalis IRAN 3 7 Balad 12 Al-Muqdadiya Heet 9 DIYALA 7 Baquba 10 4 Baladruz Al-Kadhmiyah 5 1 Al-Ramadi 9 Al-Mada'in 1 AL-ANBAR Al-Falluja 24 28 Al-Mahmoudiya Badra 3 8 Al-Suwaira Al-Mussyab JORDAN Al-Rutba 2 1 WASSIT 2 KERBALA Al-Mahaweel 3 Al-Kut Kerbela 1 BABIL 5 2 Al-Hashimiya 3 1 2 Al-Kufa 3 Al-Diwaniya Afaq 2 MAYSAN Al-Manathera 1 1 Al-Rifai Al-Hamza AL-NAJAF Al-Rumaitha 1 1 Al-Shatra * Total number of unique partners reported under the HRP 2020, HRP 2021 and other non-HRP plans Al-Najaf 2 Al-Khidhir THI QAR 2 7 Al-Nasiriya 1 Al-Qurna Suq 1 1 2 Shat 119 Partners Al-Shoyokh 3 Al-Arab Providing humanitarian assistance from January to June Al-Basrah 3 2021 for humanitarian activities under the HRP 2021, HRP 2020 AL-BASRAH Abu SAUDI ARABIA AL-MUTHANNA 4 1 other non-HRP programmes. -

Local Policing in Iraq Post-Isil

LOCAL POLICING IN IRAQ POST-ISIL CARVING OUT AN ARENA FOR COMMUNITY SERVICE? Jessica Watkins, Falah Mubarak Bardan, Abdulkareem al- Jarba, Thaer Shaker Mahmoud, Mahdi al-Delaimi, Abdulazez Abbas al-Jassem, Moataz Ismail Khalaf, Dhair Faysal Bidewi LSE Middle East Centre Paper Series | 51 | July 2021 About the Middle East Centre The Middle East Centre builds on LSE’s long engagement with the Middle East and provides a central hub for the wide range of research on the region carried out at LSE. The Middle East Centre aims to enhance un- derstanding and develop rigorous research on the societies, economies, polities and interna- tional relations of the region. The Centre pro- motes both specialised knowledge and public understanding of this crucial area and has out- standing strengths in interdisciplinary research and in regional expertise. As one of the world’s leading social science institutions, LSE com- prises departments covering all branches of the social sciences. The Middle East Centre harnesses this expertise to promote innovative research and training on the region. Middle East Centre Local Policing in Iraq Post-ISIL: Carving Out an Arena for Community Service? Jessica Watkins, Falah Mubarak Bardan, Abdulkareem al-Jarba, Thaer Shaker Mahmoud, Mahdi al-Delaimi, Abdulazez Abbas al- Jassem, Moataz Ismail Khalaf and Dhair Faysal Bidewi LSE Middle East Centre Paper Series | 51 July 2021 About the Authors Abstract Jessica Watkins is a Visiting Fellow at the Since 2003, frequent outbreaks of LSE Middle East Centre, and a Research violence in Iraq have led to a heavily mili- Associate at the German Institute for tarised local police force. -

Iraq: Buttressing Peace with the Iraqi Inter-Religious Congress

Religion and Conflict Case Study Series Iraq: Buttressing Peace with the Iraqi Inter-Religious Congress August 2013 © Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs http://berkleycenter.georgetown.edu/resources/classroom 4 Abstract 5 This case study shines a light on the sectarian violence that overtook Iraq after the 2003 US-led invasion that overthrew Saddam Hussein, and how religious 9 leaders gradually gained recognition as resources for the promotion of peace. This overview of the conflict addresses five main questions: What religious 11 factors contributed to insecurity in post-2003 Iraq? How did Coalition forces approach religious actors prior to 2006? How did governments interface with faith-based NGOs in pursuit of peace? What role did socioeconomic factors 14 play in exacerbating conflict? How did religious engagement intersect with the Sunni Awakening and the surge of Coalition troops in 2007? The case study includes a core text, a timeline of key events, a guide to relevant religious orga- nizations, and a list of further readings. 15 About this Case Study 17 This case study was crafted under the editorial direction of Eric Patterson, visiting assistant professor in the Department of Government and associate di- rector of the Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs at George- town University. This case study was made possible through the support of the Henry Luce Foundation and the Luce/SFS Program on Religion and International Affairs. 2 BERKLEY CENTER FOR RELIGION, PEACE & WORLD AFFAIRS AT GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY CASE STUDY — IRAQ Contents Introduction 4 Historical Background 5 Domestic Factors 9 International Factors 11 Religion and Socioeconomic Factors 12 Conclusion 14 Resources Key Events 15 Religious Organizations 17 Further Reading 19 Discussion Questions 21 BERKLEY CENTER FOR RELIGION, PEACE & WORLD AFFAIRS AT GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY CASE STUDY — IRAQ 3 Introduction While the US invasion of Iraq—and the insurgency that a shaky relationship with the United States. -

Kurdistan Rising? Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region

KURDISTAN RISING? CONSIDERATIONS FOR KURDS, THEIR NEIGHBORS, AND THE REGION Michael Rubin AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE Kurdistan Rising? Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region Michael Rubin June 2016 American Enterprise Institute © 2016 by the American Enterprise Institute. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or reproduced in any man- ner whatsoever without permission in writing from the American Enterprise Institute except in the case of brief quotations embodied in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. The views expressed in the publications of the American Enterprise Institute are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, advisory panels, officers, or trustees of AEI. American Enterprise Institute 1150 17th St. NW Washington, DC 20036 www.aei.org. Cover image: Grand Millennium Sualimani Hotel in Sulaymaniyah, Kurdistan, by Diyar Muhammed, Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons. Contents Executive Summary 1 1. Who Are the Kurds? 5 2. Is This Kurdistan’s Moment? 19 3. What Do the Kurds Want? 27 4. What Form of Government Will Kurdistan Embrace? 56 5. Would Kurdistan Have a Viable Economy? 64 6. Would Kurdistan Be a State of Law? 91 7. What Services Would Kurdistan Provide Its Citizens? 101 8. Could Kurdistan Defend Itself Militarily and Diplomatically? 107 9. Does the United States Have a Coherent Kurdistan Policy? 119 Notes 125 Acknowledgments 137 About the Author 139 iii Executive Summary wo decades ago, most US officials would have been hard-pressed Tto place Kurdistan on a map, let alone consider Kurds as allies. Today, Kurds have largely won over Washington. -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Report No. 16850-YEM STAFF APPRAISAL REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized REPUBLIC OF YEMEN SOUTHERN GOVERNORATES RURAL DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized September 18, 1997 Rural Development, Water and Environment Departnent Public Disclosure Authorized Middle East and North Africa Region CURRENCY Yemeni Rials 125 = US$1 (at June 1, 1997) ABBREVIATIONS BDA Business Development Advisors CACB Cooperative and Agricultural Credit Bank CAS The Country Assistance Strategy CPPR Country Portfolio Performance Review EIRR Economic Internal Rate of Return FIAHS Fund for Innovative Approach in Human and Social Development GDP Gross Domestic Product GOY Government of Yemen GTZ German Technical Cooperation ICB International Competitive Bidding IDA International Development Association IFAD International Fund for Agricultural Development IU Irrigation Unit M&E Monitoring and Evaluation MAWR Ministry of Agriculture and Water Resources MENA Middle East and North Africa MIS Management Information System MOPD Ministry of Planning and Development MSE Micro and Small Enterprises NCB National Competitive Bidding NGO Non-Governmental Organization NWRA National Water Resources Authority OC Operations Committee O&M Operation and Maintenance PDC Participatory Development Coordinators PDRY People's Democratic Republic of Yemen PHRD Policy and Human Resource Development (Japanese grant) PMU Project Management Unit PNA Participatory Needs Assessment ROY Republic of Yemen SDR Special Drawing Right -

What Are the Effects of US Involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan Since The

C3 TEACHERS World History and Geography II Inquiry (240-270 Minutes) What are the effects of US involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan since the Gulf War? This inquiry was designed by a group of high school students in Fairfax County Public Schools, Virginia. US Marines toppling a statue of Saddam Hussein in Firdos Square, Baghdad, on April 9, 2003 https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/the-fate-of-a-leg-of-a-statue-of-saddam-hussein Supporting Questions 1. What are the economic effects of US involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan since the Gulf War? 2. What are the political effects of US involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan since the Gulf War? 3. What are the social effects of US involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan since the Gulf War? THIS WORK IS LICENSE D UNDER A CREATIVE C OMMONS ATTRIBUTION - N ONCOMMERCIAL - SHAREAL I K E 4 . 0 INTERNATIONAL LICENS E. 1 C3 TEACHERS Overview - What are the effects of US involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan since the Gulf War? What are the effects of US involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan since the Gulf War? VUS.14 The student will apply social science skills to understand political and social conditions in the United States during the early twenty-first century. Standards and Content WHII.14 The student will apply social science skills to understand the global changes during the early twenty-first century. HOOK: Option A: Students will go through a see-think-wonder thinking routine based off the primary source Introducing the depicting the toppling of a statue of Saddam Hussein, as seen on the previous page.