Local Policing in Iraq Post-Isil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rebooting U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq

Rebooting U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq MICHAEL KNIGHTS POLICY FOCUS 137 Rebooting U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq MICHAEL KNIGHTS THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY www.washingtoninstitute.org The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessarily those of The Washington Institute, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2015 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050 Washington, DC 20036 Design: 1000colors Photo: A Kurdish fighter keeps guard while overlooking positions of Islamic State mili- tants near Mosul, northern Iraq, August 2014. (REUTERS/Youssef Boudlal) CONTENTS Acknowledgments | v Acronyms | vi Executive Summary | viii 1 Introduction | 1 2 Federal Government Security Forces in Iraq | 6 3 Security Forces in Iraqi Kurdistan | 26 4 Optimizing U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq | 39 5 Issues and Options for U.S. Policymakers | 48 About the Author | 74 TABLES 1 Effective Combat Manpower of Iraq Security Forces | 8 2 Assessment of ISF and Kurdish Forces as Security Cooperation Partners | 43 FIGURES 1 ISF Brigade Order of Battle, January 2015 | 10 2 Kurdish Brigade Order of Battle, January 2015 | 28 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My thanks to a range of colleagues for their encouragement and assistance in the writing of this study. -

The Case of the Iraqi Disputed Territories Declaration Submitted By

Title: Education as an Ethnic Defence Strategy: The Case of the Iraqi Disputed Territories Declaration Submitted by Kelsey Jayne Shanks to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Politics, October 2013. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Kelsey Shanks ................................................................................. 1 Abstract The oil-rich northern districts of Iraq were long considered a reflection of the country with a diversity of ethnic and religious groups; Arabs, Turkmen, Kurds, Assyrians, and Yezidi, living together and portraying Iraq’s demographic makeup. However, the Ba’ath party’s brutal policy of Arabisation in the twentieth century created a false demographic and instigated the escalation of identity politics. Consequently, the region is currently highly contested with the disputed territories consisting of 15 districts stretching across four northern governorates and curving from the Syrian to Iranian borders. The official contest over the regions administration has resulted in a tug-of-war between Baghdad and Erbil that has frequently stalled the Iraqi political system. Subsequently, across the region, minority groups have been pulled into a clash over demographic composition as each disputed districts faces ethnically defined claims. The ethnic basis to territorial claims has amplified the discourse over linguistic presence, cultural representation and minority rights; and the insecure environment, in which sectarian based attacks are frequent, has elevated debates over territorial representation to the height of ethnic survival issues. -

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION IRAQ at a CROSSROADS with BARHAM SALIH DEPUTY PRIME MINISTER of IRAQ Washington, D.C. Monday, October

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION IRAQ AT A CROSSROADS WITH BARHAM SALIH DEPUTY PRIME MINISTER OF IRAQ Washington, D.C. Monday, October 22, 2007 Introduction and Moderator: MARTIN INDYK Senior Fellow and Director, Saban Center for Middle East Policy The Brookings Institution Featured Speaker: BARHAM SALIH Deputy Prime Minister of Iraq * * * * * 2 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. INDYK: Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. Welcome to The Saban Center for Middle East Policy at the Brookings Institution. I'm Martin Indyk, the Director of the Saban Center, and it's my pleasure to introduce this dear friend, Dr. Barham Salih, to you again. I say again because, of course, Barham Salih is a well-known personality in Washington, having served here with distinction representing the patriotic Union of Kurdistan in the 1990s, and, of course, he's been a frequent visitor since he assumed his current position as Deputy Prime Minister of the Republic of Iraq. He has a very distinguished record as a representative of the PUK, and the Kurdistan regional government. He has served as Deputy Prime Minister, first in the Iraqi interim government starting in 2004, and was then successfully elected to the transitional National Assembly during the January 2005 elections and joined the transitional government as Minister of Planning. He was elected again in the elections of December 2005 to the Council of Representatives, which is the Iraqi Permanent Parliament, and was then called upon to join the Iraqi government in May 2006 as Deputy Prime Minister. Throughout this period he has had special responsibility for economic affairs. -

Who Takes the Blame the Strategic Effects of Collateral Damage

Who Takes the Blame? The Strategic Effects of Collateral Damage Luke N. Condra University of Pittsburgh Jacob N. Shapiro Princeton University Can civilians caught in civil wars reward and punish armed actors for their behavior? If so, do armed actors reap strategic benefits from treating civilians well and pay for treating them poorly? Using precise geo-coded data on violence in Iraq from 2004 through 2009, we show that both sides are punished for the collateral damage they inflict. Coalition killings of civilians predict higher levels of insurgent violence and insurgent killings predict less violence in subsequent periods. This symmetric reaction is tempered by preexisting political preferences; the anti-insurgent reaction is not present in Sunni areas, where the insurgency was most popular, and the anti-Coalition reaction is not present in mixed areas. Our findings have strong policy implications, provide support for the argument that information civilians share with government forces and their allies is a key constraint on insurgent violence, and suggest theories of intrastate violence must account for civilian agency. “When the Americans fire back, they don’t hit the of the interaction between civilians and armed actors in people who are attacking them, only the civilians. civil wars have shown that both outcomes are possible (cf. This is why Iraqis hate the Americans so much. This Stanton 2009; Valentino 2004). Attacks that harm non- is why we love the mujahedeen.”1 —Osama Ali combatants may undermine civilian support or solidify 24-year-old Iraqi it depending on the nature of the violence, the intention- ality attributed to it, and the precision with which it is “If it is accepted that the problem of defeating the applied (Downes 2007; Kalyvas 2006; Kocher, Pepinksy, enemy consists very largely of finding him, it is easy and Kalyvas 2011). -

Peace Message for Iraq Illuminates Erbil Citadel

UNAMI Newsletter United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq Newsletter - Issue 5 September 2010 IN THIS ISSUE Peace message for Iraq illuminates Erbil Citadel Peace message for Iraq illuminates Erbil Citadel ……………………………. 1 United Nations in Iraq celebrates the International Day of Peace ………… 2 A survivor's answer to violence: help Iraqi youth build peace in Iraq ……….. 3 Championing for peace in Kirkuk, Iraq. 3 A little peace picnic …………………… 4 On the census in Iraq: Speech of DSRSG Jerzy Skuratowicz ………….. 4 The Representative of the Secretary- General on the Human Rights of Internally Displaced Persons visits Iraq …………………………………….. 5 Toward strengthening the monitoring and reporting of grave violations against children in Iraq……………….. 5 Iraq adopts UN plan to transform state The Peace Day slogan put up at the Erbil Citadel. Photo: UNAMI PIO/ Laila Shamji -owned enterprises into corporations ...…………………………. 6 s part of the world wide celebration of urgent preventive works on ten of the European Union helps improve the International Day of Peace which Citadel’s most unstable buildings. UNESCO is schools and quality of education in southern Iraq ………………………….. 6 A falls on 21 September each year, also working with national authorities in their UNAMI raised and illuminated on 19 efforts to enlist the site in the World Heritage United Nations helps tackle illiteracy in September a fluorescent sign of the 2010 List. Iraq ……………………………………… 7 peace day slogan Peace=Future: The Math is Government of Iraq approves a UNAMI collaborated closely with the offices of Easy in Erbil, Kurdistan Region of Iraq. national school feeding programme … 8 the Governor of Erbil and the High Iraq’s first National Health Accounts Scripted and illuminated in the Kurdish Commission for Erbil Citadel Revitalization in survey completed ……………………. -

Edmonds Cecil John (1889-1979) Diplomat Dates of Creation of Material: 1910-1977 Level of Description: Fonds Extent: 28 Boxes

EDMONDS GB165-0095 Reference code: GB165-0095 Title: Cecil John Edmonds Collection Name of creator: Edmonds Cecil John (1889-1979) Diplomat Dates of creation of material: 1910-1977 Level of description: Fonds Extent: 28 boxes Biographical history: Edmonds, Cecil John (1889-1979) Diplomat Born 26 October 1889, youngest son of Revd. Walter and Laura Edmonds. Educated at Bedford School; Christ’s Hospital and Pembroke College, Cambridge. Joined Levant Consular Service as Student Interpreter, 1910; acting Vice-Consul, Bushire, 1913; Assistant Political Officer in Mesopotamia, 1915 (Temp. Captain), SW Persia, 1917; Political Officer, British Forces NW Persia, 1919 (Temp. Major, Special List); Special Duty in S. Kurdistan, 1922; Divisional Adviser and Administrative Inspector in the Kirkuk and Sulaimani provinces under Iraq Govt., 1922; Political Officer with military columns in Kurdistan in 1924; Liaison Officer with League of Nations Commission of Inquiry into frontier between Iraq and Turkey, 1925; Asst. Adviser, Min. of Interior, Iraq, 1926; Consul, 1928; British Assessor, League of Nations Commission of Inquiry into the frontier between Iraq and Syria, 1932; Member Of Demarcation Commission of Iraqi-Syrian Frontier, 1933; Adviser, Min. For Foreign Affairs, Iraq, 1933; Member of Iraqi Delegation to the League of Nations, annually, 1932-38; Adviser to the Ministry of the Interior, Iraq, 1935-45; Consul-General, 1937; CMG 1941; UK Permanent Delegate to International Refugee Organisation in 1947; Minister in HM Foreign Service, 1948; retired, 1950. Lecturer in Kurdish at SOAS, 1951-57. Married 1st, 1935, Alison Hooper - 1 son & 2 daughters; 2nd., 1947, Phyllis Stephenson - 1 son. Died 11 June 1979. Scope and content: Papers, correspondence and maps relating to Edmonds’ work in the consular service in North Persia, Iraq and Kurdistan. -

Pdf | 505.8 Kb

WHO Representative’s Office in Iraq Weekly Situation Report on Cholera in Iraq Sitrep no. 30; Date of Reporting: 28 October 2007 (week 43). 1. NEW LABORATORY-CONFIRMED CHOLERA CASES REPORTED DURING 22-28 OCTOBER 2007 (WEEK 43): a. Kirkuk: 28 (of 479 samples tested) 6% b. Sulaymaniyah: 39(of 660 samples tested) 6% c. Erbil: 24 (of 487samples tested) 5% 2. OVERVIEW As of 28 October 2007 (week 43), 28 districts of Northern Iraq and 16 districts in the south and centre have reported laboratory-confirmed cases of cholera. In northern Iraq, 13 out of the 14 districts of Sulaymaniyah governorate, all five districts of Kirkuk governorate, 6 of seven districts of Erbil governorate, 4 districts in Dahuk. As for the centre and south; the affected districts are: 3 districts in each of Baghdad; Tikrit; Mosul and Diyala, 2 districts in Basra as well as one district in each of Wassit, and Anbar. The results of the samples of vibrio cholerae isolates from Sulaymaniyah were received by the U.S. Naval Medical Research Unit No. 3 (NAMRU-3) laboratory, Cairo. NAMRU-3 results confirmed Sulaymaniyah- and Central Public Health Laboratory (CPHL) results, showing vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor Inaba. 99% of Iraq’s cholera cases were reported from Kirkuk, Sulaymaniyah and Erbil, northern Iraq. Sporadic cases with definite history of travel and food consumption in Kirkuk were reported from Tikrit province; however, isolated cases with no epidemiological link to northern Iraq were also confirmed in Mosul, Wassit, Baghdad, Anbar and Basra. One of the important features in this outbreak is that most of the cases seen have mild to moderate signs and symptoms. -

Geographical Variation in the Prevalence of Female Genital Mutilation in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq

Research article EMHJ – Vol. 25 No. 9 – 2019 Geographical variation in the prevalence of female genital mutilation in the Kurdistan region of Iraq Nazar Shabila 1 1Hawler Medical University, Erbil, Iraq (Correspondence to Nazar P. Shabila: [email protected]). Abstract Background: Female genital mutilation is practised in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq but the reasons for this are not well understood. Aims: This study aimed to determine the geographical clustering of female genital mutilation in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Methods: A secondary analysis of data from the Iraq Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2011 was done. The sample includ- ed 11 384 women of reproductive age who reported having undergone genital mutilation. The prevalence of female genital was analysed according to Iraqi governorate including the three governorates of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, district of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, and age group (15–30 and 31–49 years). Results: The prevalence of female genital mutilation was highest in Erbil (62.9%) and Sulaimany (55.8%) governorates in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. The prevalence was highest in the districts of Pishdar (98.1%), Rania (95.1%), Choman (88.5%), Dukan (83.8%) and Koya (80.4%). In 20 of the 33 districts, the prevalence of female genital mutilation was significantly lower in the younger age group (15–30 years). The difference between the two age groups was small and not statistically significant in the districts of Pishdar, Rania and Dukan. The main cluster of districts with a high prevalence of female genital mutilation is located in the eastern part of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq along the border with the Islamic Republic of Iran. -

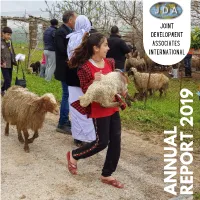

A N N U a L R E P O R T 2 0 19

JOINT DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATES INTERNATIONAL 9 1 0 2 L T A R U O N P N E A R Table of Contents Letter from the CEO 2 Mission/ Areas of Work 4 Background of Beneficiary Groups Iraq 5 Iraq RIVAL Program 6 Beneficiary Stories RIVAL 9 Afghanistan RADP-North Program 11 Water Access 14 Hygiene & Nutrition 16 Emergency Relief 17 Days for Girls 18 Financial Statement 19 Board of Directors 20 Pictured on the front cover is a Yazidi girl helping her mother carry lamb. Her mother is one of 250 beneficiaries who received a livestock grant through our RIVAL program which allowed her to buy two ewes and two lambs. Woman receiving a start up income grant. J D A I N T E R N A T I O N A L | 1 Letter from the CEO Thank you for making 2019 another exceptional year! The year marked the beginning of a chapter and the end of another. Our highlight of the year has been the Returnees, IDPs, Vulnerable Iraqis Attain Livelihoods (RIVAL) program in Iraq. The focus of the program is to assist in the rehabilitation of lives and livelihoods of refugees, internally displaced persons (IDPs), and other vulnerable persons. We are working within minority Chaldean and Yazidi communities. Program outreach is primarily through cash for work opportunities, small business grants, and agricultural training. In the first year of the program we have served 2,296 beneficiaries and their families. We look forward to the program's second year and hope to extend into a third and fourth year. -

Kirkuk Governoratre Profile.Indd

KIRKUK GOVERNORATE PROFILE OVERVIEW3 JUNE 2015 1,515 IDP families 2% 61,831 IDP FAMILIES 42,390 IDP families 69% IDP camps 370,986 IDP INDIVIDUALS total population: 13,737 ndividuals1 planned: 21,120 individuals DISPLACEMENT OVER TIME IDP families hosted in the governorate2 IDP population 36% OF ALL IDPS ARE UNDER density IDP families who originate from the gover- 14 norate 59,230 61,83162,941 71,568 OF ALL IDP 12,281 IDP families 58,184 56,885 20% 57,482 INDIVIDUALS ACROSS IRAQ ORIGINATED FROM KIRKUK Laylan Yayawah 39,796 30,492 GOVERNORATE OF ORIGIN 28,534 22,064 19,779 11,92812,813 ll IDPs in 5,645 IDP families 10,295 10,737 f a Ir 11,198 28% o a 9% q 38% % 2,665 6,578 11,027 11,383 10,349 2 4,227 10,189 1 1,379 2,915 2,117 - - - 914 8% 14 14 14 15 14 14 14 15 14 14 14 15 15 15 14 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 9% 17% Jul Jan Jun Oct Apr Apr Sep Feb Dec Aug Nov Mar Mar May May 99% Anbar Babylon Baghdad MOST COMMON SHELTER TYPES Diyala Kirkuk Ninewa INTENTIONS Salah al-Din WAVES OF DISPLACEMENT Iraq 3% 87% 8% ? Kirkuk 9% 99% 1% 23% Total 28% Rented Unknown4 Unfinished/ housing 57% 14% Abandoned Kirkuk 99% 1% buildings 12% Daquq 100% TOP PRIORITY NEEDS 31% 1 2 3 4 5 Dabes 100% 18% Locally integrate in current location Return to place of origin 90% Waiting on one or several factors Access Shelter Health NFIs Food 1- Pre-June14 2- June-July14 to work 3- August14 4- Post September14 1. -

Maternal and Neonatal Health in Select Districts of Iraq: Findings

ncy gna and re C P h f Moazzem Hossain et al., J Preg Child Health 2018, 5:5 il o d l H a e n DOI: 10.4172/2376-127X.1000395 a r l u t h o J Journal of Pregnancy and Child Health ISSN: 2376-127X Research Article Article OpenOpen Access Access Maternal and Neonatal Health in Select Districts of Iraq: Findings from a Recent Household Survey SM Moazzem Hossain1*, Shatha El Nakib2, Shaimaa Ibrahim1, Abdullah-Al-Harun3, Suham Muhammad4, Nabila Zaka5, Khulood Oudah6 and Ihsaan Jaffar6 1United Nations Children’s Fund, Iraq 2Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, USA 3BRAC International, Bangladesh 4Central Statistical Organization, Iraq 5United Nations Children’s Fund, NY USA 6Ministry of Health, Government of Iraq, Iraq Abstract The dearth of updated data on Maternal Neonatal and Child Health (MNCH) indicators in Iraq hampers efforts for evidence-based programming. To address this gap, a cross-sectional household survey was carried out among 7,182 households. The aim of the survey was to assess the status of MNCH in select districts of Iraq where the Iraq Every Newborn Action plan is to be Implemented, and to investigate sociodemographic disparities in MNCH outcomes and service coverage. We used two-stage cluster sampling, selected 25 primary sampling units with probability proportional to size, and sampled 24 households per sampling unit in 12 districts. The total number of women included in the analysis were 7,222. The under-five mortality rate calculated was 37 deaths per 1000 live births and the neonatal mortality was 23 deaths per 1000 live births, accounting for more than half of under-five deaths. -

Climate Change Risks and Opportunities in Iraqi Agrifood Value Chainsy Saavi

This project is funded by the European Union CLIMATE CHANGE RISKS AND OPPORTUNITIES CHAINSY CHANGE RISKS IRAQI IN VALUE CLIMATE AGRIFOOD Climate change risks and opportunities in Iraqi agrifood value chains Strengthening the Agriculture and Agrifood Value Chain and Improving Trade Policy in Iraq (SAAVI) SAAVI This project is funded by the European Union Climate change risks and opportunities in Iraqi agrifood value chains Strengthening the Agriculture and Agrifood Value Chain and Improving Trade Policy in Iraq ( SAAVI ) ii Climate change risks and opportunities in Iraqi agrifood value chains – SAAVI ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The study Climate changes risks and opportunities in Iraqi agri-food value chains was prepared by Lorenzo Formenti, Associate Sustainable Development Officer, under the supervision of Alexander Kasterine, Senior Advisor, both from the Sustainable and Inclusive Value Chains section of the International Trade Centre ( ITC ). The study presents the findings of the Climate and Environment Risk Assessment ( CERA ) conducted to support the project’s environmental mainstreaming as- sessment and approach, Strengthening the Agriculture and Agrifood Value Chain and Improving Trade Policy in Iraq ( SAAVI ), funded by the European Union. The project is implemented under the leadership of the Government of Iraq through the Ministry of Planning ( MoP ), Ministry of Agriculture ( MoA ) and Ministry of Trade ( MoT ). It forms part of a series of assessments conducted in agrifood supply chains across the globe to ensure that principles of climate resilience and environmental sustainability are incorporated in the ITC project design. The authors are grateful to Eric Buchot, SAAVI Project Coordinator, Ky Phong Nguyen, SAAVI Project Officer, and Vanessa Erogbogbo, Chief of the Sustainable and Inclusive Value Chains section, who supported the process.