Interview Magazine: Art & Fame

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moma Andy Warhol Motion Pictures

MoMA PRESENTS ANDY WARHOL’S INFLUENTIAL EARLY FILM-BASED WORKS ON A LARGE SCALE IN BOTH A GALLERY AND A CINEMATIC SETTING Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures December 19, 2010–March 21, 2011 The International Council of The Museum of Modern Art Gallery, sixth floor Press Preview: Tuesday, December 14, 10:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m. Remarks at 11:00 a.m. Click here or call (212) 708-9431 to RSVP NEW YORK, December 8, 2010—Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures, on view at MoMA from December 19, 2010, to March 21, 2011, focuses on the artist's cinematic portraits and non- narrative, silent, and black-and-white films from the mid-1960s. Warhol’s Screen Tests reveal his lifelong fascination with the cult of celebrity, comprising a visual almanac of the 1960s downtown avant-garde scene. Included in the exhibition are such Warhol ―Superstars‖ as Edie Sedgwick, Nico, and Baby Jane Holzer; poet Allen Ginsberg; musician Lou Reed; actor Dennis Hopper; author Susan Sontag; and collector Ethel Scull, among others. Other early films included in the exhibition are Sleep (1963), Eat (1963), Blow Job (1963), and Kiss (1963–64). Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures is organized by Klaus Biesenbach, Chief Curator at Large, The Museum of Modern Art, and Director, MoMA PS1. This exhibition is organized in collaboration with The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. Twelve Screen Tests in this exhibition are projected on the gallery walls at large scale and within frames, some measuring seven feet high and nearly nine feet wide. An excerpt of Sleep is shown as a large-scale projection at the entrance to the exhibition, with Eat and Blow Job shown on either side of that projection; Kiss is shown at the rear of the gallery in a 50-seat movie theater created for the exhibition; and Sleep and Empire (1964), in their full durations, will be shown in this theater at specially announced times. -

Post Layout 1

22 Established 1961 Lifestyle Fashion Sunday, September 9, 2018 Tom Ford kicks off New York Fashion Week ew York Fashion Week opened with a bang Victoria Beckham is celebrating the 10th anniversary of with a masterclass from Tom Ford, A-list mod- her brand in London. Tommy Hilfiger held his show in Nels oozing subdued sophistication in neutral Shanghai on Tuesday, the latest pit-stop on what has palettes with Tom Hanks and break-out rom-com star been a global tour since declining to show in the Big Henry Golding front row. The US city kicks off a Apple since September 2016. month-long fashion merry-go-round in which editors, Alexander Wang, the king of cool, has switched to a celebrities and influencers descend first on the Big June-December schedule and plenty of others make lit- Apple before jetting off to fashion weeks in London, tle secret of their a thirst for something new in a city Milan and Paris. that constantly glorifies innovation. “What we know Everyone from the biggest names in the industry to traditionally as fashion week-and I love a runway US model Gigi Hadid fresh-out-of-college hopefuls will pack a frenetic show-is changing,” designer Zac Posen told CNBC this schedule from Thursday to September 12 as the Big week. “It’s a very saturated field, so you have to find Apple wilts under a late summer heatwave. Ford took a interesting creative ways of cutting through the mar- chill pill-opening the spring/summer 2019 season by ket.” His answer? Unveil his collection in a photo shoot sending down the runway models Kaia Gerber, Gigi starring up-and-coming actress Maya Hawke, daughter Hadid, Joan Smalls in matte make-up, headscarves and of Ethan and Uma Thurman.—AFP smokey eyes. -

Lucy Sparrow Photo: Dafydd Jones 18 Hot &Coolart

FREE 18 HOT & COOL ART YOU NEVER FELT LUCY SPARROW LIKE THIS BEFORE DAFYDD JONES PHOTO: LUCY SPARROW GALLERIES ONE, TWO & THREE THE FUTURE CAN WAIT OCT LONDON’S NEW WAVE ARTISTS PROGRAMME curated by Zavier Ellis & Simon Rumley 13 – 17 OCT - VIP PREVIEW 12 OCT 6 - 9pm GALLERY ONE PETER DENCH DENCH DOES DALLAS 20 OCT - 7 NOV GALLERY TWO MARGUERITE HORNER CARS AND STREETS 20 - 30 OCT GALLERY ONE RUSSELL BAKER ICE 10 NOV – 22 DEC GALLERY TWO NEIL LIBBERT UNSEEN PORTRAITS 1958-1998 10 NOV – 22 DEC A NEW NOT-FOR-PROFIT LONDON EXHIBITION PLATFORM SUPPORTING THE FUSION OF ART, PHOTOGRAPHY & CULTURE Art Bermondsey Project Space, 183-185 Bermondsey Street London SE1 3UW Telephone 0203 441 5858 Email [email protected] MODERN BRITISH & CONTEMPORARY ART 20—24 January 2016 Business Design Centre Islington, London N1 Book Tickets londonartfair.co.uk F22_Artwork_FINAL.indd 1 09/09/2015 15:11 THE MAYOR GALLERY FORTHCOMING 21 CORK STREET, FIRST FLOOR, LONDON W1S 3LZ TEL: +44 (0) 20 7734 3558 FAX: +44 (0) 20 7494 1377 [email protected] www.mayorgallery.com EXHIBITIONS WIFREDO ARCAY CUBAN STRUCTURES THE MAYOR GALLERY 13 OCT - 20 NOV Wifredo Arcay (b. 1925, Cuba - d. 1997, France) “ETNAIRAV” 1959 Latex paint on plywood relief 90 x 82 x 8 cm 35 1/2 x 32 1/4 x 3 1/8 inches WOJCIECH FANGOR WORKS FROM THE 1960s FRIEZE MASTERS, D12 14 - 18 OCT Wojciech Fangor (b.1922, Poland) No. 15 1963 Oil on canvas 99 x 99 cm 39 x 39 inches STATE_OCT15.indd 1 03/09/2015 15:55 CAPTURED BY DAFYDD JONES i SPY [email protected] EWAN MCGREGOR EVE MAVRAKIS & Friend NICK LAIRD ZADIE SMITH GRAHAM NORTON ELENA SHCHUKINA ALESSANDRO GRASSINI-GRIMALDI SILVIA BRUTTINI VANESSA ARELLE YINKA SHONIBARE NIMROD KAMER HENRY HUDSON PHILIP COLBERT SANTA PASTERA IZABELLA ANDERSSON POPPY DELEVIGNE ALEXA CHUNG EMILIA FOX KARINA BURMAN SOPHIE DAHL LYNETTE YIADOM-BOAKYE CHIWETEL EJIOFOR EVGENY LEBEDEV MARC QUINN KENSINGTON GARDENS Serpentine Gallery summer party co-hosted by Christopher Kane. -

Warhol, Andy (As Filmmaker) (1928-1987) Andy Warhol

Warhol, Andy (as filmmaker) (1928-1987) Andy Warhol. by David Ehrenstein Image appears under the Creative Commons Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Courtesy Jack Mitchell. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com As a painter Andy Warhol (the name he assumed after moving to New York as a young man) has been compared to everyone from Salvador Dalí to Norman Rockwell. But when it comes to his role as a filmmaker he is generally remembered either for a single film--Sleep (1963)--or for works that he did not actually direct. Born into a blue-collar family in Forest City, Pennsylvania on August 6, 1928, Andrew Warhola, Jr. attended art school at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh. He moved to New York in 1949, where he changed his name to Andy Warhol and became an international icon of Pop Art. Between 1963 and 1967 Warhol turned out a dizzying number and variety of films involving many different collaborators, but after a 1968 attempt on his life, he retired from active duty behind the camera, becoming a producer/ "presenter" of films, almost all of which were written and directed by Paul Morrissey. Morrissey's Flesh (1968), Trash (1970), and Heat (1972) are estimable works. And Bad (1977), the sole opus of Warhol's lover Jed Johnson, is not bad either. But none of these films can compare to the Warhol films that preceded them, particularly My Hustler (1965), an unprecedented slice of urban gay life; Beauty #2 (1965), the best of the films featuring Edie Sedgwick; The Chelsea Girls (1966), the only experimental film to gain widespread theatrical release; and **** (Four Stars) (1967), the 25-hour long culmination of Warhol's career as a filmmaker. -

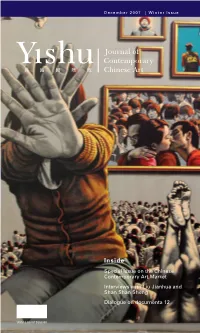

Inside Special Issue on the Chinese Contemporary Art Market Interviews with Liu Jianhua and Shan Shan Sheng Dialogue on Documenta 12

December 2007 | Winter Issue Inside Special Issue on the Chinese Contemporary Art Market Interviews with Liu Jianhua and Shan Shan Sheng Dialogue on documenta 12 US$12.00 NT$350.00 china square 1 2 Contents 4 Editor’s Note 6 Contributors 8 Contemporary Chinese Art: To Get Rich Is Glorious 11 Britta Erickson 17 The Surplus Value of Accumulation: Some Thoughts Martina Köppel-Yang 19 Seeing Through the Macro Perspective: The Chinese Art Market from 2006 to 2007 Zhao Li 23 Exhibition Culture and the Art Market 26 Yü Christina Yü 29 Interview with Zheng Shengtian at the Seven Stars Bar, 798, Beijing Britta Erickson 34 Beyond Selling Art: Galleries and the Construction of Art Market Norms Ling-Yun Tang 44 Taking Stock Joe Martin Hill 41 51 Everyday Miracles: National Pride and Chinese Collectors of Contemporary Art Simon Castets 58 Superfluous Things: The Search for “Real” Art Collectors in China Pauline J. Yao 62 After the Market’s Boom: A Case Study of the Haudenschild Collection 77 Michelle M. McCoy 72 Zhong Biao and the “Grobal” Imagination Paul Manfredi 84 Export—Cargo Transit Mathieu Borysevicz 90 About Export—Cargo Transit: An Interview with Liu Jianhua 87 Chan Ho Yeung David 93 René Block’s Waterloo: Some Impressions of documenta 12, Kassel Yang Jiechang and Martina Köppel-Yang 101 Interview with Shan Shan Sheng Brandi Reddick 109 Chinese Name Index 108 Yishu 22 errata: On page 97, image caption lists director as Liang Yin. Director’s name is Ying Liang. On page 98, image caption lists director as Xialu Guo. -

The Economist Print Edition

The Pop master's highs and lows Nov 26th 2009 From The Economist print edition Andy Warhol is the bellwether The Andy Warhol Foundation $100m-worth of Elvises “EIGHT ELVISES” is a 12-foot painting that has all the virtues of a great Andy Warhol: fame, repetition and the threat of death. The canvas is also awash with the artist’s favourite colour, silver, and dates from a vintage Warhol year, 1963. It did not leave the home of Annibale Berlingieri, a Roman collector, for 40 years, but in autumn 2008 it sold for over $100m in a deal brokered by Philippe Ségalot, the French art consultant. That sale was a world record for Warhol and a benchmark that only four other artists—Pablo Picasso, Jackson Pollock, Willem De Kooning and Gustav Klimt— have ever achieved. Warhol’s oeuvre is huge. It consists of about 10,000 artworks made between 1961, when the artist gave up graphic design, and 1987, when he died suddenly at the age of 58. Most of these are silk-screen paintings portraying anything from Campbell’s soup cans to Jackie Kennedy and Mao Zedong, drag queens and commissioning collectors. Warhol also created “disaster paintings” from newspaper clippings, as well as abstract works such as shadows and oxidations. The paintings come in series of various sizes. There are only 20 “Most Wanted Men” canvases, for example, but about 650 “Flower” paintings. Warhol also made sculpture and many experimental films, which contribute greatly to his legacy as an innovator. The Warhol market is considered the bellwether of post-war and contemporary art for many reasons, including its size and range, its emblematic transactions and the artist’s reputation as a trendsetter. -

The Rise of Pop

Expos 20: The Rise of Pop Fall 2014 Barker 133, MW 10:00 & 11:00 Kevin Birmingham (birmingh@fas) Expos Office: 1 Bow Street #223 Office Hours: Mondays 12:15-2 The idea that there is a hierarchy of art forms – that some styles, genres and media are superior to others – extends at least as far back as Aristotle. Aesthetic categories have always been difficult to maintain, but they have been particularly fluid during the past fifty years in the United States. What does it mean to undercut the prestige of high art with popular culture? What happens to art and society when the boundaries separating high and low art are gone – when Proust and Porky Pig rub shoulders and the museum resembles the supermarket? This course examines fiction, painting and film during a roughly ten-year period (1964-1975) in which reigning cultural hierarchies disintegrated and older terms like “high culture” and “mass culture” began to lose their meaning. In the first unit, we will approach the death of the high art novel in Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49, which disrupts notions of literature through a superficial suburban American landscape and through the form of the novel itself. The second unit turns to Andy Warhol and Pop Art, which critics consider either an American avant-garde movement undermining high art or an unabashed celebration of vacuous consumer culture. In the third unit, we will turn our attention to The Rocky Horror Picture Show and the rise of cult films in the 1970s. Throughout the semester, we will engage art criticism, philosophy and sociology to help us make sense of important concepts that bear upon the status of art in modern society: tradition, craftsmanship, community, allusion, protest, authority and aura. -

Andy Warhol: When Junkies Ruled the World

Nebula 2.2 , June 2005 Andy Warhol: When Junkies Ruled the World. By Michael Angelo Tata So when the doorbell rang the night before, it was Liza in a hat pulled down so nobody would recognize her, and she said to Halston, “Give me every drug you’ve got.” So he gave her a bottle of coke, a few sticks of marijuana, a Valium, four Quaaludes, and they were all wrapped in a tiny box, and then a little figure in a white hat came up on the stoop and kissed Halston, and it was Marty Scorsese, he’d been hiding around the corner, and then he and Liza went off to have their affair on all the drugs ( Diaries , Tuesday, January 3, 1978). Privileged Intake Of all the creatures who populate and punctuate Warhol’s worlds—drag queens, hustlers, movie stars, First Wives—the drug user and abuser retains a particular access to glamour. Existing along a continuum ranging from the occasional substance dilettante to the hard-core, raging junkie, the consumer of drugs preoccupies Warhol throughout the 60s, 70s and 80s. Their actions and habits fascinate him, his screens become the sacred place where their rituals are projected and packaged. While individual substance abusers fade from the limelight, as in the disappearance of Ondine shortly after the commercial success of The Chelsea Girls , the loss of status suffered by Brigid Polk in the 70s and 80s, or the fatal overdose of exemplary drug fiend Edie Sedgwick, the actual glamour of drugs remains, never giving up its allure. 1 Drugs survive the druggie, who exists merely as a vector for the 1 While Brigid Berlin continues to exert a crucial influence on Warhol’s work in the 70s and 80s—for example, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol , as detailed by Bob Colacello in the chapter “Paris (and Philosophy )”—her street cred. -

Andy Warhol¬タルs Deaths and the Assembly-Line Autobiography

OCAD University Open Research Repository Faculty of Liberal Arts & Sciences and School of Interdisciplinary Studies 2011 Andy Warhol’s Deaths and the Assembly-Line Autobiography Charles Reeve OCAD University [email protected] © University of Hawai'i Press | Available at DOI: 10.1353/bio.2011.0066 Suggested citation: Reeve, Charles. “Andy Warhol’s Deaths and the Assembly-Line Autobiography.” Biography 34.4 (2011): 657–675. Web. ANDY WARHOL’S DEATHS AND THE ASSEMBLY-LINE AUTOBIOGRAPHY CHARLES REEVE Test-driving the artworld cliché that dying young is the perfect career move, Andy Warhol starts his 1980 autobiography POPism: The Warhol Sixties by refl ecting, “If I’d gone ahead and died ten years ago, I’d probably be a cult fi gure today” (3). It’s vintage Warhol: off-hand, image-obsessed, and clever. It’s also, given Warhol’s preoccupation with fame, a lament. Sustaining one’s celebrity takes effort and nerves, and Warhol often felt incapable of either. “Oh, Archie, if you would only talk, I wouldn’t have to work another day in my life,” Bob Colacello, a key Warhol business functionary, recalls the art- ist whispering to one of his dachshunds: “Talk, Archie, talk” (144). Absent a talking dog, maybe cult status could relieve the pressure of fame, since it shoots celebrities into a timeless realm where their notoriety never fades. But cults only reach diehard fans, whereas Warhol’s posthumously pub- lished diaries emphasize that he coveted the stratospheric stardom of Eliza- beth Taylor and Michael Jackson—the fame that guaranteed mobs wherever they went. (Reviewing POPism in the New Yorker, Calvin Tomkins wrote that Warhol “pursued fame with the single-mindedness of a spawning salmon” [114].) Even more awkwardly, cult status entails dying—which means either you’re not around to enjoy your notoriety or, Warhol once nihilistically pro- posed, you’re not not around to enjoy it. -

Council of Fashion Designers of America

Council of Fashion Designers of America ANNUAL REPORT 2018 The mission of the Council of Fashion Designers of America is to strengthen the impact of American fashion in the global economy. B Letter from the Chairwoman, Diane von Furstenberg When I became President of the CFDA 13 years ago, I had two initials goals—to turn the American fashion community into a family and to make it more global. Letter from the The first adventure Steven and I went on was to Washington, D.C., President & Chief to lobby for copyright protection for fashion designers. It was quite an experience to lobby to almost everybody in Congress, from John Executive Officer, McCain to Maxine Waters, Hillary Clinton, and Nancy Pelosi. While we didn’t manage to pass legislation, we did manage to give the Steven Kolb subject so much exposure—in Washington and beyond—that a lot of the people who used to copy realized the importance of hiring Much has changed since I started at CFDA thirteen years ago. original talent to lead their design teams. The Internet and social media have revolutionized the fashion Creating a family means coming together and supporting each other. landscape. Everything is immediately universal and faster, and We launched the Strategic Partnerships Group, which provides tangible everybody has a platform to express their views. In fashion, we used business services, education, and work opportunities for our designers. to talk among ourselves a lot. Now, we must listen to all the voices and engage with the world. As the digital revolution and the influence of social media were changing our industry, we felt obligated to reevaluate the purpose of This year, we introduced the CFDA Fashion Trust with Tania Fares, Fashion Week and empower the designers to do what’s best for each which brings in individuals and corporations to raise funds for U.S.-based one of them. -

Red, Yellow, Blue Lauren Elizabeth Eyler University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2013 Red, Yellow, Blue Lauren Elizabeth Eyler University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Creative Writing Commons Recommended Citation Eyler, L. E.(2013). Red, Yellow, Blue. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/2315 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RED, YELLOW, BLUE by Lauren Eyler Bachelor of Arts Georgetown University, 2005 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2013 Accepted by: Elise Blackwell, Director of Thesis David Bajo, Reader John Muckelbauer, Reader Agnes Mueller, Reader Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Lauren Eyler, 2013 All Rights Reserved. ii ABSTRACT Red, Yellow, Blue is a hybrid, metafictional novel/autobiography. The work explores the life of Ellis, Lotte, Diana John-John and Lauren as they wander through a variety of circumstances, which center on loss and grief. As the novel develops, the author loses control over her intentionality; the character’s she claims to know fuse together, leaving the reader to wonder if Lauren is synonymous with Ellis or if Diana is actually Lotte disguised by a signifier. Red, Yellow, Blue questions the author’s as well as the reader’s ability to understand the transformation that occurs in an individual during long periods of grief and anxiety. -

Wonder Waif Meets Super Neuter

Wonder Waif Meets Super Neuter CATHERINE LORD “As far as I’m concerned, the guy was a fucking saint.”1 The fucking saint is Michel Foucault. The guy who wrote the sentence is David Halperin, whose Saint Foucault: Toward a Gay Hagiography is one of the most battered books in my library. I scribble and underline not because I revere Michel Foucault, or David, although I do, in different ways, but because I cannot resist a good polemic: Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis, for example, Malcolm X on white devils, and Yvonne Rainer’s No to everything she could think of in 1965. To write a polemic is a for- mal challenge. It is to connect the most miniscule of details with the widest of panoramas, to walk a tightrope between rage and reason, to insist that ideas are nothing but lived emotion, and vice versa. To write a polemic is to try to dig oneself out of the grave that is the margin, that already shrill, already colored, already feminized, already queered location in which words, any words, any com- bination of words are either symptoms of madness or proof incontrovertible of guilt by association. Halperin’s beatification of Foucault is a disciplined absur- dity, at once an evisceration of homophobia and an aria to the fashioning of a queer self. You don’t get to be a saint without pulling off a miracle or two. Foucault’s History of Sexuality was, says Halperin, the “single most important source of political 1. David M. Halperin, Saint Foucault: Towards a Gay Hagiography (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), p.