Russian 280 Introduction to Russian Civilization Bulletin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Musorgsky's Boris Godunov

22 JANUARY 2019 Musorgsky’s Boris Godunov PROFESSOR MARINA FROLOVA-WALKER Today we are going to look at what is possibly the most famous of Russian operas – Musorgsky’s Boris Godunov. Its route to international celebrity is very clear – the great impresario Serge Diaghilev staged it in Paris in 1908, with the star bass Fyodor Chaliapin in the main role. The opera the Parisians saw would have taken Musorgsky by surprise. First, it was staged in a heavily reworked edition made by Rimsky-Korsakov after Musorgsky’s death, where only about 20% of the bars in the original were left unchanged. But that was still a modest affair compared to the steps Diaghilev took on his own initiative. The production had a Russian cast singing the opera in Russian, and Diaghilev was worried that the Parisians would lose patience with scenes that were more wordy, since they would follow none of it, so he decided simply to cut these scenes, even though this meant that some crucial turning points in the drama were lost altogether. He then reordered the remaining scenes to heighten contrasts, jumbling the chronology. In effect, the opera had become a series of striking tableaux rather than a drama with a coherent plot. But as pure spectacle, it was indeed impressive, with astonishing sets provided by the painter Golovin and with the excitement generated by Chaliapin as Boris. For all its shortcomings, it was this production that brought Musorgsky’s masterwork to the world’s attention. 1908, the year of the Paris production was nearly thirty years after Musorgsky’s death, and nearly and forty years after the opera was completed. -

The Transformation of Pushkin's Eugene Onegin Into Tchaikovsky's Opera

THE TRANSFORMATION OF PUSHKIN'S EUGENE ONEGIN INTO TCHAIKOVSKY'S OPERA Molly C. Doran A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2012 Committee: Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Megan Rancier © 2012 Molly Doran All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Since receiving its first performance in 1879, Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky’s fifth opera, Eugene Onegin (1877-1878), has garnered much attention from both music scholars and prominent figures in Russian literature. Despite its largely enthusiastic reception in musical circles, it almost immediately became the target of negative criticism by Russian authors who viewed the opera as a trivial and overly romanticized embarrassment to Pushkin’s novel. Criticism of the opera often revolves around the fact that the novel’s most significant feature—its self-conscious narrator—does not exist in the opera, thus completely changing one of the story’s defining attributes. Scholarship in defense of the opera began to appear in abundance during the 1990s with the work of Alexander Poznansky, Caryl Emerson, Byron Nelson, and Richard Taruskin. These authors have all sought to demonstrate that the opera stands as more than a work of overly personalized emotionalism. In my thesis I review the relationship between the novel and the opera in greater depth by explaining what distinguishes the two works from each other, but also by looking further into the argument that Tchaikovsky’s music represents the novel well by cleverly incorporating ironic elements as a means of capturing the literary narrator’s sardonic voice. -

COCKEREL Education Guide DRAFT

VICTOR DeRENZI, Artistic Director RICHARD RUSSELL, Executive Director Exploration in Opera Teacher Resource Guide The Golden Cockerel By Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov Table of Contents The Opera The Cast ...................................................................................................... 2 The Story ...................................................................................................... 3-4 The Composer ............................................................................................. 5-6 Listening and Viewing .................................................................................. 7 Behind the Scenes Timeline ....................................................................................................... 8-9 The Russian Five .......................................................................................... 10 Satire and Irony ........................................................................................... 11 The Inspiration .............................................................................................. 12-13 Costume Design ........................................................................................... 14 Scenic Design ............................................................................................... 15 Q&A with the Queen of Shemakha ............................................................. 16-17 In The News In The News, 1924 ........................................................................................ 18-19 -

Three Poems on the Death of Pushkin

STEPHANIE SANDLER THE LAW, THE BODY, AND THE BOOK: THREE POEMS ON THE DEATH OF PUSHKIN ... the Cheated Eye Shuts Arrogantly-in the Grave- Another way-to See- Emily Dickinson No fact of Alexander Pushkin's life or work was so important in constructing modern mythologies of Pushkin as his death. As a preliminary effort toward understanding those modern myths, I propose here to consider three nineteenth-century poems on Pushkin's death, all written soon thereafter. Mikhail Lermontov's "Smert' poeta" ("The Death of the Poet," 1837) de- fined Pushkin's death as an act of social violence and created a powerful discourse about Pushkin's death based on moral judgment. His definition itself constituted a symbolic act in Russian political and cultural life: "Smert' poeta" attained great authority for succeeding generations' writings about Pushkin's death and about the political context of his life. Less well-known accounts by Vasilii Zhukovskii and Countess Evdokiia Rostopchina will show more personal and strictly historical responses, foreshadowing the unorthodox responses of some of Pushkin's later readers. At the time of his death in a duel in 1837, Alexander Pushkin was admired as Russia's great national poet. Though his fame had declined during the 1830s, crowds who waited for news of the dying poet revealed how much Pushkin was loved and how pro- found was Russia's loss. The transformation of the death into tributes to his greatness began at once,l and Lermontov's "Smert' 1. For a survey of nineteenth-century poems about Pushkin, see R. V. Iezuitova, "Evoliutsiia obraza Pushkina v russkoi poezii XIX veka," Pushkin: Issledovaniia i materialy, 5 (1967), 113-39. -

Russian History: a Brief Chronology (998-2000)

Russian History: A Brief Chronology (998-2000) 1721 Sweden cedes the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea to Russia (Treaty of Nystad). In celebration, Peter’s title Kievan Russia is changed from tsar to Emperor of All Russia Abolition of the Patrarchate of Moscow. Religious authority passes to the Holy Synod and its Ober- prokuror, appointed by the tsar. 988 Conversion to Christianity 1722 Table of Ranks 1237-1240 Mongol Invasion 1723-25 The Persian Campaign. Persia cedes western and southern shores of the Caspian to Russia Muscovite Russia 1724 Russia’s Academy of Sciences is established 1725 Peter I dies on February 8 1380 The Battle of Kulikovo 1725-1727 Catherine I 1480 End of Mongol Rule 1727-1730 Peter II 1462-1505 Ivan III 1730-1740 Anne 1505-1533 Basil III 1740-1741 Ivan VI 1533-1584 Ivan the Terrible 1741-1762 Elizabeth 1584-98 Theodore 1744 Sophie Friederike Auguste von Anhalt-Zerbst arrives in Russia and assumes the name of Grand Duchess 1598-1613 The Time of Troubles Catherine Alekseevna after her marriage to Grand Duke Peter (future Peter III) 1613-45 Michael Romanoff 1762 Peter III 1645-76 Alexis 1762 Following a successful coup d’etat in St. Petersburg 1672-82 Theodore during which Peter III is assassinated, Catherine is proclaimed Emress of All Russia Imperial Russia 1762-1796 Catherine the Great 1767 Nakaz (The Instruction) 1772-1795 Partitions of Poland 1682-1725 Peter I 1773-1774 Pugachev Rebellion 1689 The Streltsy Revolt and Suppression; End of Sophia’s Regency 1785 Charter to the Nobility 1695-96 The Azov Campaigns 1791 Establishment fo the Pale of Settlement (residential restrictions on Jews) in the parts of Poland with large 1697-98 Peter’s travels abroad (The Grand Embassy) Jewish populations, annexed to Russia in the partitions of Poland (1772, 1793, and 1795) and in the 1698 The revolt and the final suppression of the Streltsy Black Sea liitoral annexed from Turkey. -

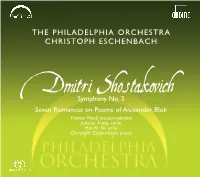

Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No

Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 1 THE PHILADELPHIA ORCHESTRA CHRISTOPH ESCHENBACH Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No. 5 Seven Romances on Poems of Alexander Blok Yvonne Naef,mezzo-soprano Juliette Kang,violin Hai-Ye Ni,cello CHristoph EschenbacH,piano Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 2 ESCHENBACH CHRISTOPH • ORCHESTRA H bac hen c s PHILADELPHIA E THE oph st i r H C 2 Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 3 Dmitri ShostakovicH (1906–1975) Symphony No. 5 Seven Romances in D minor,Op. 47 (1937) on Poems of Alexander Blok,Op. 127 (1967) ESCHENBACH 1 I.Moderato – Allegro 5 I.Ophelia’s Song 3:01 non troppo 17:37 6 II.Gamayun,Bird of Prophecy 3:47 2 II.Allegretto 5:49 7 III.THat Troubled Night… 3:22 3 III.Largo 16:25 8 IV.Deep in Sleep 3:05 4 IV.Allegro non troppo 12:23 9 V.The Storm 2:06 bu VI.Secret Signs 4:40 CHRISTOPH • bl VII.Music 5:36 The Philadelphia Orchestra Yvonne Naef,mezzo-soprano CHristoph EschenbacH,conductor Juliette Kang,violin* Hai-Ye Ni ,cello* CHristoph EschenbacH ,piano ORCHESTRA *members of The Philadelphia Orchestra [78:15] Live Recordings:Philadelphia,Verizon Hall,September 2006 (Symphony No. 5) & Perelman Theater,May 2007 (Seven Romances) Executive Producer:Kevin Kleinmann Recording Producer:MartHa de Francisco Balance Engineer and Editing:Jean-Marie Geijsen – PolyHymnia International Recording Engineer:CHarles Gagnon Musical Editors:Matthijs Ruiter,Erdo Groot – PolyHymnia International PHILADELPHIA Piano:Hamburg Steinway prepared and provided by Mary ScHwendeman Publisher:Boosey & Hawkes Ondine Inc. -

History Is Made in the Dark 4: Alexander Nevsky: the Prince, the Filmmaker and the Dictator

1 History Is Made in the Dark 4: Alexander Nevsky: The Prince, the Filmmaker and the Dictator In May 1937, Sergei Eisenstein was offered the opportunity to make a feature film on one of two figures from Russian history, the folk hero Ivan Susanin (d. 1613) or the mediaeval ruler Alexander Nevsky (1220-1263). He opted for Nevsky. Permission for Eisenstein to proceed with the new project ultimately came from within the Kremlin, with the support of Joseph Stalin himself. The Soviet dictator was something of a cinephile, and he often intervened in Soviet film affairs. This high-level authorisation meant that the USSR’s most renowned filmmaker would have the opportunity to complete his first feature in some eight years, if he could get it through Stalinist Russia’s censorship apparatus. For his part, Eisenstein was prepared to retreat into history for his newest film topic. Movies on contemporary affairs often fell victim to Soviet censors, as Eisenstein had learned all too well a few months earlier when his collectivisation film, Bezhin Meadow (1937), was banned. But because relatively little was known about Nevsky’s life, Eisenstein told a colleague: “Nobody can 1 2 find fault with me. Whatever I do, the historians and the so-called ‘consultants’ [i.e. censors] won’t be able to argue with me”.i What was known about Alexander Nevsky was a mixture of history and legend, but the historical memory that was most relevant to the modern situation was Alexander’s legacy as a diplomat and military leader, defending a key western sector of mediaeval Russia from foreign foes. -

Boris Godunov

Boris Godunov and Little Tragedies Alexander Pushkin Translated by Roger Clarke FE<NFIC; :C8JJ@:J ONEWORLD CLASSICS LTD London House 243-253 Lower Mortlake Road Richmond Surrey TW9 2LL United Kingdom www.oneworldclassics.com Boris Godunov first published in Russian in 1831 The Mean-Spirited Knight first published in Russian in 1836 Mozart and Salieri first published in Russian in 1831 The Stone Guest first published in Russian in 1839 A Feast during the Plague first published in Russian in 1832 This translation first published by Oneworld Classics Limited in 2010 English translations, introductions, notes, extra material and appendices © Roger Clarke, 2010 Front cover image © Catriona Gray Printed in Great Britain by MPG Books, Cornwall ISBN: 978-1-84749-147-3 All the material in this volume is reprinted with permission or presumed to be in the public domain. Every effort has been made to ascertain and acknowledge the copyright status, but should there have been any unwitting oversight on our part, we would be happy to rectify the error in subsequent printings. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher. Contents Boris Godunov 1 Introduction by Roger Clarke 3 Boris Godunov 9 Little Tragedies 105 Introduction by Roger Clarke 107 The Mean-Spirited Knight 109 Mozart and Salieri 131 The Stone Guest 143 A Feast during the Plague 181 Notes on Boris Godunov 193 Notes on Little Tragedies 224 Extra Material 241 Alexander Pushkin’s Life 243 Boris Godunov 251 Little Tragedies 262 Translator’s Note 280 Select Bibliography 282 Appendices 285 1. -

The Inextricable Link Between Literature and Music in 19Th

COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Ashley Shank December 2010 COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA Ashley Shank Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor Interim Dean of the College Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Dudley Turner _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. George Pope Dr. George R. Newkome _______________________________ _______________________________ School Director Date Dr. William Guegold ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. OVERVIEW OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF SECULAR ART MUSIC IN RUSSIA……..………………………………………………..……………….1 Introduction……………………..…………………………………………………1 The Introduction of Secular High Art………………………………………..……3 Nicholas I and the Rise of the Noble Dilettantes…………………..………….....10 The Rise of the Russian School and Musical Professionalism……..……………19 Nationalism…………………………..………………………………………..…23 Arts Policies and Censorship………………………..…………………………...25 II. MUSIC AND LITERATURE AS A CULTURAL DUET………………..…32 Cross-Pollination……………………………………………………………...…32 The Russian Soul in Literature and Music………………..……………………...38 Music in Poetry: Sound and Form…………………………..……………...……44 III. STORIES IN MUSIC…………………………………………………… ….51 iii Opera……………………………………………………………………………..57 -

The Historical Legacy for Contemporary Russian Foreign Policy

CHAPTER 1 The Historical Legacy for Contemporary Russian Foreign Policy o other country in the world is a global power simply by virtue of geogra- N phy.1 The growth of Russia from an isolated, backward East Slavic principal- ity into a continental Eurasian empire meant that Russian foreign policy had to engage with many of the world’s principal centers of power. A Russian official trying to chart the country’s foreign policy in the 18th century, for instance, would have to be concerned simultaneously about the position and actions of the Manchu Empire in China, the Persian and Ottoman Empires (and their respec- tive vassals and subordinate allies), as well as all of the Great Powers in Europe, including Austria, Prussia, France, Britain, Holland, and Sweden. This geographic reality laid the basis for a Russian tradition of a “multivector” foreign policy, with leaders, at different points, emphasizing the importance of rela- tions with different parts of the world. For instance, during the 17th century, fully half of the departments of the Posolskii Prikaz—the Ambassadors’ Office—of the Muscovite state dealt with Russia’s neighbors to the south and east; in the next cen- tury, three out of the four departments of the College of International Affairs (the successor agency in the imperial government) covered different regions of Europe.2 Russian history thus bequeaths to the current government a variety of options in terms of how to frame the country’s international orientation. To some extent, the choices open to Russia today are rooted in the legacies of past decisions. -

Refractions of Rome in the Russian Political Imagination by Olga Greco

From Triumphal Gates to Triumphant Rotting: Refractions of Rome in the Russian Political Imagination by Olga Greco A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Comparative Literature) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Valerie A. Kivelson, Chair Assistant Professor Paolo Asso Associate Professor Basil J. Dufallo Assistant Professor Benjamin B. Paloff With much gratitude to Valerie Kivelson, for her unflagging support, to Yana, for her coffee and tangerines, and to the Prawns, for keeping me sane. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication ............................................................................................................................... ii Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 1 Chapter I. Writing Empire: Lomonosov’s Rivalry with Imperial Rome ................................... 31 II. Qualifying Empire: Morals and Ethics of Derzhavin’s Romans ............................... 76 III. Freedom, Tyrannicide, and Roman Heroes in the Works of Pushkin and Ryleev .. 122 IV. Ivan Goncharov’s Oblomov and the Rejection of the Political [Rome] .................. 175 V. Blok, Catiline, and the Decomposition of Empire .................................................. 222 Conclusion ........................................................................................................................... 271 Bibliography ....................................................................................................................... -

Eugene Miakinkov

Russian Military Culture during the Reigns of Catherine II and Paul I, 1762-1801 by Eugene Miakinkov A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Department of History and Classics University of Alberta ©Eugene Miakinkov, 2015 Abstract This study explores the shape and development of military culture during the reign of Catherine II. Next to the institutions of the autocracy and the Orthodox Church, the military occupied the most important position in imperial Russia, especially in the eighteenth century. Rather than analyzing the military as an institution or a fighting force, this dissertation uses the tools of cultural history to explore its attitudes, values, aspirations, tensions, and beliefs. Patronage and education served to introduce a generation of young nobles to the world of the military culture, and expose it to its values of respect, hierarchy, subordination, but also the importance of professional knowledge. Merit is a crucial component in any military, and Catherine’s military culture had to resolve the tensions between the idea of meritocracy and seniority. All of the above ideas and dilemmas were expressed in a number of military texts that began to appear during Catherine’s reign. It was during that time that the military culture acquired the cultural, political, and intellectual space to develop – a space I label the “military public sphere”. This development was most clearly evident in the publication, by Russian authors, of a range of military literature for the first time in this era. The military culture was also reflected in the symbolic means used by the senior commanders to convey and reinforce its values in the army.