How American Society Memorialized the Dead After 1945

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PHLF News Publication

Protecting the Places that Make Pittsburgh Home Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation Nonprofit Org. 1 Station Square, Suite 450 U. S. Postage Pittsburgh, PA 15219-1134 PAID www.phlf.org Pittsburgh, PA Address Service Requested Permit No. 598 PHLF News Published for the members of the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation No. 160 April 2001 Landmarks Launches Rural In this issue: 4 Preservation Program Landmarks Announces Its Gift Annuity Program Farms in Allegheny County—some Lucille C. Tooke Donates vent non-agricultural development. with historic houses, barns, and scenic Any loss in market value incurred by 10 views—are rapidly disappearing. In Historic Farm Landmarks in the resale of the property their place is urban sprawl: malls, Through a charitable could be offset by the eventual proceeds The Lives of Two North Side tract housing, golf courses, and high- remainder unitrust of the CRUT. Landmarks ways. According to information from (CRUT), long-time On December 21, 2000, Landmarks the U. S. Department of Agriculture, member Lucille C. succeeded in buying the 64-acre Hidden only 116 full-time farms remained in Tooke has made it Valley Farm from the CRUT. Mrs. Tooke 12 Allegheny County in 1997. possible for Landmarks is enjoying her retirement in Chambers- Revisiting Thornburg to acquire its first farm burg, PA and her three daughters are property, the 64-acre Hidden Valley excited about having saved the family Farm on Old State Road in Pine homestead. Landmarks is now in the 19 Township. The property includes a process of selling the protected property. Variety is the Spice of Streets house of 1835 that was awarded a “I believe Landmarks was the answer Or, Be Careful of Single-Minded Planning Historic Landmark plaque in 1979. -

April 1920) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 4-1-1920 Volume 38, Number 04 (April 1920) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 38, Number 04 (April 1920)." , (1920). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/667 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jlae Utiuiufi SPRING NUMBER 1MUUISZ5 LJEJNTS APRIL 1920 $ 2.00 A YEAR The Tonne daugrhter of the Into Tnrasn-Bonlba, a new opera by A Brrent Opera Trnst, according: to Colerldgre-Taylor is following a musical Marcel Sninuel-Houssenu, was recently report. Is being proposed in tlif« career, and has already a number of songs country, which would control all presenta¬ tions of opera, all singers, all opera houses, ■SS.rJE •! *£rS'.!Bf j" ' 1 CONTENTS FOR APRIL, 1920 sHSr!Sir'-s‘^“'s SV,s£S: APRIL 1920 Page THE ETUDE Page 218 APRIL 1920 THE Jane Novak in “The River’s End” Jane Novak is an emotional ac¬ PUPILS RECITALS AND PLEASED AUDIENCES tress of sincere power and dis¬ tinguished ability. -

How Public Art Gets Lost - and Saved - in Philly

How public art gets lost - and saved - in Philly JANUARY 8, 2016 by Samantha Melamed For fans of public art in Philadelphia, it still stings to think about that day in 1998 when word got out that an iconic wall sculpture by artist Ellsworth Kelly had been removed from the old Greyhound office building, quietly sold, and given to New York's Museum of Modern Art. It wasn't the first or last great work of public art to be lost to Philadelphia through some combination of intercity poaching, heedless development, and neglect. In fact, even as the Gallery mall closed for renovations Jan. 1, the fate of its public art remained unclear. The same goes for other works that have languished in storage, with limited money for preservation. Still, losing the work by Kelly, who died Dec. 27, wasn't entirely a bad thing, said Penny Balkin Bach, executive director of the Association for Public Art, a nonprofit that commissions, preserves, and promotes works in the city. "The removal of the Kelly was this sort of slap-in-the-face wake-up call that we needed as a city and as a cultural community to pay more attention to these kinds of things," she said. Her organization has become more proactive since, as have art fans. "Having the public's eyes and ears alert is probably our greatest protection." Now, scrap yards call her when they come across bronze sculptures they suspect have been stolen, and New York gallery owners tip her off when important works come up for sale. -

Operations RG.03

Operations RG.03 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 24, 2019. Describing Archives: A Content Standard The papers of the American Academy in Rome 7 East 60 Street New York, New York 10022 [email protected] URL: http://www.aarome.org Operations RG.03 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 4 - Page 2 - Operations RG.03 Summary Information Repository: The papers of the American Academy in Rome Title: Operations ID: RG.03 Date [inclusive]: 1895-2018 Physical Description: 209.45 Linear Feet Language of the English Material: ^ Return to Table of Contents Scope and Contents This Record Group is comprised of records that document the functions of the American Academy in Rome (AAR). Records in this group include administrative files that document the daily operations -

The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

THE PENNSYLVANIA ACADEMY OF THE FINE ARTS BROAD AND CHERRY 5T5. • PHILADELPHIA 153rd ANNUAL REPORT 1958 Cover: The Fish House Door by John F. Peto Collection Fund Purchase 1958 the One-Hundred and Fifty-third Annual Report of THE PENNSYLVANIA ACADEMY OF THE FINE ARTS FOR THE YEAR 1958 Presented to the Meeting of the Stockholders of the Academy on February 2, 1959 OFFICERS John F. Lewis, Jr. President, 1949-0ctober, 1958 Henry S. Drinker Vice-Pres., 1933-0ctober, 1958; President, October, 1958- C. Newbold Taylor . Treasurer Joseph T. Fraser, Jr. Director and Secretary BOARD OF DIRECTORS Mrs. Leonard T. Beale Arthur C. Kaufmann Howard C. Petersen Mrs. Richardson Dilworth* John F. Lewis, Jr. George B. Roberts Henry S. Drinker James P. Magill Raymond A. Speiser David Gwinn Fredric R. Mann* John Stewart George Harding* Sydney E. Martin C. Newbold Taylor Frank T. Howard Mrs. Herbert C. Morris Mrs. Elias Wolf* R. Sturgis Ingersoll George P. Orr** Sydney L. Wright * Ex-officio Alfred Zantzinger **Resigned Sept_ 1958 STANDING COMMITTEES COMM ITT EE ON COLL EC TI ONS AND EX HI BITIONS George B. Roberts, Chairman Mrs. Leonard T. Beale R. Sturgis Ingersoll Alfred Zantzinger CO MM ITTEE O N FIN AN CE C. Newbold Taylor Chairman James P. Magill John Stewart COMM ITTEE ON IN ST RU CTION James P. Magill, Chairman Mrs. Leonard T. Beale Mrs. Richardson Dilworth David Gwinn Mrs. Elias Wolf SOLICITOR Maurice B. Saul WOMEN'S COMMITTEE Mrs. Hart McMichael . Chairman to May, 1958 Mrs. Elias Wolf . Chairman, May, 1958- Mrs. George B. Roberts Corresponding Secretary-Treasurer Mrs. -

The American Legion Monthly Is the Official Publication of the American Legion and the American Legion Auxiliary and Is Owned Exclusively

QlfieMERI25 Cents CAN EGION OHonthlj/ Meredith Nicholson - Lorado Taft Arthur Somers Roche — Who wants to live on a poorly lighted street? Nobody who knows the advantages of modern lighting—the safety for drivers and pedestrians the protection against crime—the evidence of a desirable residential area. The service of General Electric's street-lighting To-day, no street need be dark, for good specialists are always at the command of communities street lighting costs as little as two dollars a year interested in better light- per capita; and for that two dollars there is a ing. In cooperation with your local power company, substantial increment in property value they will suggest appropri- ate installations, and give you the benefit of their It isn't a question whether you can afford long experience in the de- sign and operation of street- good street lighting, but— can you afford not lighting and electric traffic- control systems. to have it? GENERAL ELECTRIC S. F. ROTHAFEL— the famous Roxy—of Roxy and His Gang — builder of the world's finest theatre—known and loved by hundreds of thousands—not only for his splendid enter- tainments but for his work in bringing joy and sunshine into the lives of so many in hos- pitals and institutions. Never too busy to help—Roxy keeps himself in good physical con- dition by proper rest—on a Simmons Beautyrest Mattress and Ace Spring Anyone who has to take his rest in concentrated doses is mighty particular " about how he beds himself down doesn't know "Roxy"— his says springy wire coils and its soft mattress * ^ voice on the air has cheered millions layers is the result. -

Nomination Form

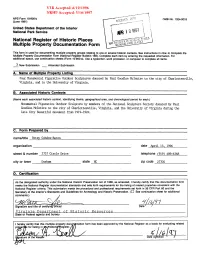

VLR Accepted: 6/19/1996 NRHP Accepted: 5/16/1997 NPS Form 10-900-b 0MB No. 1024-0018 (June 1991) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. X New Submission Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Four Monumental Figurative Outdoor Sculptures donated by Paul Goodloe McIntire to the city of Charlottesville, Virginia, and to the University of Virginia. B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Monumental Figurative Outdoor Sculpture by members of the National Sculpture Society donated by Paul Goodloe McIntire to the city of Charlottesville, Virginia, and the University of Virginia during the late City Beautiful movement fran 1919-1924. C. Form Prepared by name/title Betsy Gohdes-Baten organization date April 13, 1996 street & number 2737 Circle Drive telephone (919) 489-6368 city or town ___Du_rha_m ________ state _N_C _________ zip code --=-2--'77;_;:;0_z..5 _____ D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. -

BODILY KNOWLEDGE in DANCE TRANSFERRED to the CREATION of SCULPTURE by Nazaré Feliciano a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty

BODILY KNOWLEDGE IN DANCE TRANSFERRED TO THE CREATION OF SCULPTURE by Nazaré Feliciano A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts & Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL May 2014 Copyright by Nazaré Feliciano 2014 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation was possible because of the help and support of many others. I want to express gratitude to those who inspired me and who showed me the way. To begin, I want to express my gratitude to Mary Frank whose sculptures inspired me to write this dissertation and for her welcoming into her art studio. I wish to express sincere thanks to the members of my committee. To Dr. Brian McConnell, who believed in this project from the beginning and gave me guidance and encouragement to it’s completion. To Dr. Marcella Munson for her insights into the various dimensions of this topic. To Professor Clarence Brooks for his contagious energy and insights of the dance world. I also owe thanks to Professor Gvozden Kopani for his advice on focusing all course work assignments toward my dissertation. A special thank you to Dr. Richard Shusterman who kindly reviewed the discussion of somaesthetics in my dissertation. Deepest gratitude to my dissertation angels: To Frederick Krantz, who enthusiastically proofread and edited every chapter of this manuscript and made suggestions for better readability. To Maureen Riley who gave me support and organization guidance throughout the development of this work. Finally, I am deeply indebted to my family and friends without whose loving care and enthusiasm I wouldn’t be able to finish this project. -

Spring/Summer

friends OF THE SAINT-GAUDENS MEMORIAL CORNISH I NEW HAMPSHIRE I SUMMER 2007 (Right Augustus Saint-Gaudens in his Paris Studio, 1898. Sketch of the Amor Caritas IN THIS ISSUE SAINT-GAUDENS’ in the background. Saint-Gaudens’ Numismatic Legacy I 1 NUMISMATIC LEGACY (Below) Obverse of the high relief The Model for the 1907 Double Eagle I 4 The precedent that President 1907 Twenty Dollar A Little Known Treasure I 5 Gold Coin. Saint-Gaudens Film & Symposium I 6 Theodore Roosevelt established, Concerts and Exhibits I 7 of having academically trained Coin Exhibition I 8 sculptors design U.S. coinage, resulted in a series of remarkable coins. Many of these were created FROM THE MEMORIAL by five artists who trained under AND THE SITE Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Archival photo DEAR FRIENDS AND ANS MEMBERS, Bela Pratt (1867-1917) This Friends Newsletter from Connecticut, first studied with Saint-Gaudens In 1907, Pratt was encouraged by is dedicated to the centennial at the Art Students League Dr. William Sturgis Bigelow (185 0-1926), of Saint-Gaudens’ Ten and in New York City. He then a prominent collector of Oriental art and Twenty Dollar Gold Coins moved to Paris, where he an acquaintance of President Theodore studied under Jean Falguière (1831-1900) Roosevelt, to redesign the Two and a Half and his numismatic legacy. and Henri-Michel-Antoine Chapu (183 3- and Five Dollar Gold Coins. Pratt’s designs Augustus Saint-Gaudens, at the request 1891) at the École des Beaux-Arts. Saint- were the first American coins to have an of President Theodore Roosevelt, was the Gaudens was the first American accepted incused design, which is a relief in reverse . -

Atlanta Heritage Trails 2.3 Miles, Easy–Moderate

4th Edition AtlantaAtlanta WalksWalks 4th Edition AtlantaAtlanta WalksWalks A Comprehensive Guide to Walking, Running, and Bicycling the Area’s Scenic and Historic Locales Ren and Helen Davis Published by PEACHTREE PUBLISHERS 1700 Chattahoochee Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30318-2112 www.peachtree-online.com Copyright © 1988, 1993, 1998, 2003, 2011 by Render S. Davis and Helen E. Davis All photos © 1998, 2003, 2011 by Render S. Davis and Helen E. Davis All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without prior permission of the publisher. This book is a revised edition of Atlanta’s Urban Trails.Vol. 1, City Tours.Vol. 2, Country Tours. Atlanta: Susan Hunter Publishing, 1988. Maps by Twin Studios and XNR Productions Book design by Loraine M. Joyner Cover design by Maureen Withee Composition by Robin Sherman Fourth Edition 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Manufactured in August 2011 in Harrisonburg, Virgina, by RR Donnelley & Sons in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Davis, Ren, 1951- Atlanta walks : a comprehensive guide to walking, running, and bicycling the area’s scenic and historic locales / written by Ren and Helen Davis. -- 4th ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-56145-584-3 (alk. paper) 1. Atlanta (Ga.)--Tours. 2. Atlanta Region (Ga.)--Tours. 3. Walking--Georgia--Atlanta-- Guidebooks. 4. Walking--Georgia--Atlanta Region--Guidebooks. 5. -

Summary 1 1. INTRODUCTION A. the City of Worcester Issues This RFQ

1. INTRODUCTION A. The City of Worcester issues this RFQ for the purposes of engaging the services of a qualified professional sculpture conservator or art conservation studio (hereafter identified as the “Conservator” or the “Vendor”) to perform cleaning and conservation of twelve historic objects and monuments within the City of Worcester. B. The following sculptures and monuments are to be conserved/repaired: Wheaton Square (1898) (bronze) Celtic Cross (stone) City Hall Armor (2, metal) City Hall, Deedy Plaque (bronze) City Hall Marble Eagle (2) City Hall Mastrototoro Plaque (bronze) City Hall USS Maine Plaque (bronze) City Hall Norcross Plaque (bronze) City Hall Order of Construction Plaque (bronze) City Hall Ship Bell (bronze) Elm Park Fisher Boy (bronze and stone) Elm Park Winslow Gate (Lincoln Gate) (bronze and natural boulders) C. The Conservator will provide all supplies and materials, site safety materials including signs, caution tape, safety cones, and plastic sheeting. D. The Conservator will provide weekly updates to the project manager. E. Schedule for Work: all work must begin and be completed by dates agreed upon by the selected Conservator and the City of Worcester. F. The Conservator will be responsible for erecting scaffold as needed, and providing ladders as needed, except for historic objects within Worcester City Hall, where the Facilities Department will provide access. 2. REQUIRED SERVICES: PROFESSIONAL ART CONSERVATION TREATMENT A. The Conservator shall implement all conservation services according to the treatments to be carried out according to the Standards for Practice outlined by the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, including: surface cleaning of sculptures and monuments, removal of previous coatings as specified, repatination of bronze to correct historic color, removal of old or Summary 1 inappropriate coatings or over paint, structural repairs as specified, restoration of missing elements as specified in individual reports and with consultation with the project manager. -

Hartwood-RFQ.Pdf

Request for Qualifications for An Outdoor Sculpture Commission at Hartwood Acres Park Release date: Friday, October 30, 2020 Allegheny County Parks Foundation in Partnership with Allegheny County Budget: $100,000 Deadline: December 21, 2020 at 4:00 PM EST SUMMARY The Allegheny Parks Foundation in partnership with Allegheny County is soliciting proposals from individual artists or an artist team to install sculptural work outside at Hartwood Acres, one of the nine county parks. The artist or artist team will work in collaboration with the Allegheny County Parks Foundation to coordinate the design, fabrication and installation of the new artwork. The budget for this project is $100,000. PROJECT DESCRIPTION The Allegheny County Parks Foundation strengthens the health and vibrancy of the community by improving, conserving and restoring the nine parks in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. Working in partnership with Allegheny County, the Parks Foundation brings together ideas, leadership and resources to make the parks more sustainable and enjoyable for all. Originally designed as a country estate for an equestrian family, Hartwood Acres Park channels its opulent past in 629 acres of beauty. The original bridle trails still serve runners, bikers and cross-country skiers today. The park is well-known for its popular outdoor entertainment, including free summer concerts at the amphitheater. The newest treasure is the reimagined Hartwood Acres Sculpture Garden, an outdoor exhibition space for public art. Eleven sculptures were gifted to Hartwood Acres Park in the 1980s, when it was envisioned as an arts and culture park. A twelfth sculpture was added years later and another is on loan from the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh.