Heinonline (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LINCOLN's OFFICIAL FAMILY-Bffiuography

LINCOLN LORE Bulletin of the Lincoln National Life Foundation -- --- Dr. Louis A. WarreniEditor Published each week by The Lincoln National Life Insurance Company, Fort Wayne, ndlana Number 753 FORT WAYNE, INDIANA September 13, 1943 LINCOLN'S OFFICIAL FAMILY-BffiUOGRAPHY Sometimes the appearance of a new Salmon P. Chase, 1861-1864 Seward, F. W., Stward at Wa8hington book will call to the attention of the 1.18 Senat<w and Secretary of State, public a considerable number of titles Schuckers, J. W., Life and Public Serv· ices of Salm<m Portland Clwse, 1846·1881, 650pp., 1891. with which it may be classified. Gideon Seward, F. W., Seward at Washington \Velles, Lincoln's Navy Department, 669pp., 1874. is such a book. Chase, S. P., AgaimJt tl~ Re,Jealof the as Sent~.t<w and Secretary of State, Missottri Prohibition of Suwery, 1861-187!, 561pp., 1891. Just outside the pale which separates 16pJ>., 1854. Bancroft, F., Life of William H. Sew· Lincolniana from a general library is ard, 2 vols., 1900. an indefinite number of books called Luthin, R. H., Salmon P. Chase'tt P(}o collateral items. A bibliography of this litical Career Bef&re the Civil ll'ar. Seward, 0. R., William H. Seward's (23) pp., 1943. Travel• Arormd the World, 730pp., large number of Lincoln J'cference 1873. items has never been attempted, except Chase, S. P., Diary and Cor-rcttpon· in Civil War compilations, where many tlence of S. P. Cl1.0.11c, 2 vols., 1903. Seward, W. H., Recent SpeecJwg and of them properly belong, yet, most of Writing• of William H. -

Treason on Trial: the United States V. Jefferson Davis'

H-Nationalism Walser on Icenhauer-Ramirez, 'Treason on Trial: The United States v. Jefferson Davis' Review published on Monday, March 29, 2021 Robert Icenhauer-Ramirez. Treason on Trial: The United States v. Jefferson Davis. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2019. 376 pp. $55.00 (cloth),ISBN 978-0-8071-7080-9. Reviewed by Heather C. Walser (The Pennsylvania State University) Published on H-Nationalism (March, 2021) Commissioned by Evan C. Rothera (University of Arkansas - Fort Smith) Printable Version: https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=56425 In Treason on Trial: The United States v. Jefferson Davis, Robert Icenhauer-Ramirez explores why the United States failed to prosecute Jefferson Davis for treason in the years following the US Civil War. When federal troops arrested the former Confederate president outside of Irwinville, Georgia, in the early morning hours of May 10, 1865, few questioned whether Davis would face treason charges. Considering Davis’s role as the leader of the Confederacy, accusations about his involvement in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, and President Andrew Johnson’s well-known stance regarding the need to make treason “odious,” prosecution of Davis seemed inevitable. But as Icenhauer-Ramirez skillfully demonstrates, any efforts to successfully try Davis for treason hinged on the capabilities and willingness of multiple individuals involved in the prosecution. According toTreason on Trial, the inability of the prosecution to determine when and where Davis should be tried, the reluctance of Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase to actively participate in the case in his role as judge, and the skillful use of the countless delays by Davis’s attorneys and wife crippled the prosecution and resulted in Davis’s release from federal custody in December 1868 as a free, and fully pardoned, man. -

Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution

Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Collection of Essays Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Collection of Essays Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission Kentucky Heritage Council © Essays compiled by Alicestyne Turley, Director Underground Railroad Research Institute University of Louisville, Department of Pan African Studies for the Kentucky African American Heritage Commission, Frankfort, KY February 2010 Series Sponsors: Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Kentucky Historical Society Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission Kentucky Heritage Council Underground Railroad Research Institute Kentucky State Parks Centre College Georgetown College Lincoln Memorial University University of Louisville Department of Pan African Studies Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission The Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission (KALBC) was established by executive order in 2004 to organize and coordinate the state's commemorative activities in celebration of the 200th anniversary of the birth of President Abraham Lincoln. Its mission is to ensure that Lincoln's Kentucky story is an essential part of the national celebration, emphasizing Kentucky's contribution to his thoughts and ideals. The Commission also serves as coordinator of statewide efforts to convey Lincoln's Kentucky story and his legacy of freedom, democracy, and equal opportunity for all. Kentucky African American Heritage Commission [Enabling legislation KRS. 171.800] It is the mission of the Kentucky African American Heritage Commission to identify and promote awareness of significant African American history and influence upon the history and culture of Kentucky and to support and encourage the preservation of Kentucky African American heritage and historic sites. -

1 Updated: 1/4/2019 2:21 PM

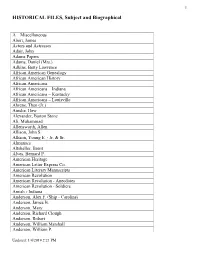

1 HISTORICAL FILES, Subject and Biographical A – Miscellaneous Abert, James Actors and Actresses Adair, John Adams Papers Adams, Daniel (Mrs.) Adkins, Betty Lawrence African American Genealogy African American History African Americans African Americans – Indiana African Americans – Kentucky African Americans – Louisville Ahrens, Theo (Jr.) Ainslie, Hew Alexander, Barton Stone Ali, Muhammad Allensworth, Allen Allison, John S. Allison, Young E. - Jr. & Sr. Almanacs Altsheller, Brent Alves, Bernard P. American Heritage American Letter Express Co. American Literary Manuscripts American Revolution American Revolution - Anecdotes American Revolution - Soldiers Amish - Indiana Anderson, Alex F. (Ship - Caroline) Anderson, James B. Anderson, Mary Anderson, Richard Clough Anderson, Robert Anderson, William Marshall Anderson, William P. Updated: 1/4/2019 2:21 PM 2 Andressohn, John C. Andrew's Raid (James J. Andrews) Antiques - Kentucky Antiquities - Kentucky Appalachia Applegate, Elisha Archaeology - Kentucky Architecture and Architects Architecture and Architects – McDonald Bros. Archival Symposium - Louisville (1970) Archivists and Archives Administration Ardery, Julia Spencer (Mrs. W. B.) Ark and Dove Arnold, Jeremiah Arthur Kling Center Asbury, Francis Ashby, Turner (Gen.) Ashland, KY Athletes Atkinson, Henry (Gen.) Audubon State Park (Henderson, KY) Augusta, KY Authors - KY Authors - KY - Allen, James Lane Authors - KY - Cawein, Madison Authors - KY - Creason, Joe Authors - KY - McClellan, G. M. Authors - KY - Merton, Thomas Authors - KY - Rice, Alice Authors - KY - Rice, Cale Authors - KY - Roberts, Elizabeth Madox Authors - KY - Sea, Sophie F. Authors - KY - Spears, W. Authors - KY - Still, James Authors - KY - Stober, George Authors - KY - Stuart, Jesse Authors - KY - Sulzer, Elmer G. Authors - KY - Warren, Robert Penn Authors - Louisville Auto License Automobiles Updated: 1/4/2019 2:21 PM 3 Awards B – Miscellaneous Bacon, Nathaniel Badin, Theodore (Rev.) Bakeless, John Baker, James G. -

Abraham Lincoln Papers

Abraham Lincoln papers From Thomas Worcester to Abraham Lincoln, May 16, 1864 Dear Sir, It is a constant subject of thankfulness with me, that you are where you are. And it is my belief that the Divine Providence is using your honesty, kindness, patience and intelligence as means of carrying us through our present troubles. 1 I see that you hesitate with regard to retaliation, and I am glad of it. Your feelings of kindness and regard to justice do not allow you to take the severe course, which is most obvious. Now I feel great confidence that you will be led to the best conclusions; but while you are hesitating, I am tempted to offer a suggestion. 1 This is a reference to the Fort Pillow massacre that occurred on April 12 when black soldiers attempted to surrender and were given no quarter. Lincoln carefully considered an appropriate response to this outrage. On May 3, he convened a meeting of the cabinet and requested each member to submit a written opinion that recommended a course of action to take in response to the massacre. At a cabinet meeting on May 6, each member read his opinion on the case and after receiving this advice, Lincoln began to draft a set of instructions for Secretary of War Stanton to implement. Apparently Lincoln became distracted by other matters, such as Grant's campaign against Lee and these instructions were neither completed nor submitted to the War Department. For the written opinions of the cabinet, see Edward Bates to Lincoln, May 4, 1864; William H. -

Abraham Lincoln: Preserving the Union and the Constitution

ABRAHAM LINCOLN: PRESERVING THE UNION AND THE CONSTITUTION Louis Fisher* I. THE MEXICAN WAR ..................................................................505 A. Polk Charges Treason ...................................................507 B. The Spot Resolutions ....................................................508 C. Scope of Presidential Power .........................................510 II. DRED SCOTT DECISION ...........................................................512 III. THE CIVIL WAR .....................................................................513 A. The Inaugural Address.................................................515 B. Resupplying Fort Sumter .............................................518 C. War Begins ...................................................................520 D. Lincoln’s Message to Congress .....................................521 E. Constitutionality of Lincoln’s Actions .......................... 523 F. Suspending the Writ .....................................................524 G. Statutory Endorsement ................................................527 H. Lincoln’s Blockade .......................................................528 IV. COMPARING POLK AND LINCOLN ...........................................531 * Specialist in constitutional law, Law Library, Library of Congress. This paper was presented at the Albany Government Law Review’s symposium, “Lincoln’s Legacy: Enduring Lessons of Executive Power,” held on September 30 and October 1, 2009. My appreciation to David Gray Adler, Richard -

Frank and Virginia Williams Collection of Lincolniana Original Manuscripts FVWCL.2019.003

Frank and Virginia Williams Collection of Lincolniana Original Manuscripts FVWCL.2019.003 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 12, 2019. Mississippi State University Libraries P.O. Box 5408 Mississippi State 39762 [email protected] URL: http://library.msstate.edu/specialcollections Frank and Virginia Williams Collection of Lincolniana Original Manuscripts FVWCL.2019.003 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical .................................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 6 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Series 1: Abraham Lincoln Legal Documents, 1837-1859 ........................................................................ 6 Series 2: Abraham Lincoln Correspondence, 1852-1865 .......................................................................... -

The First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation Compiled by the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

The First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation Compiled by the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution Target Grade Level: 4–12 in United States history classes Objectives After completing this lesson, students will be better able to: • Identify and analyze key components of a portrait and relate visual elements to relevant historical context and significance. • Evaluate provisions of the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln's reasons for issuing it, and its significance. Portrait The First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation By Alexander Hay Ritchie, after Francis Bicknell Carpenter Stipple engraving, 1866 National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Mrs. Chester E. King NPG.78.109 Link >> Background Information for Teachers Background Information for Teachers: First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation (depicting a scene that took place on July 22, 1862) Pictured, left to right: Secretary of War Edwin Stanton; Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase; President Abraham Lincoln; Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles; Secretary of State William H. Seward (seated); Secretary of the Interior Caleb Smith; Postmaster General Montgomery Blair; Attorney General Edward Bates Pictured on the table: a copy of the Constitution of the United States; a map entitled The Seat of War in Virginia; Pictured on the floor: two volumes of Congressional Globe; War Department portfolio; “Commentaries on the Constitution”; “War Powers of the President”; and a map showing the country’s slave population Portrait Information: The painter of the original work, Francis Carpenter, spent six months in Abraham Lincoln’s White House in 1864, reconstructing the scene on July 22, 1862, when Lincoln read the first draft of his Emancipation Proclamation to his cabinet. -

The Appointment of Supreme Court Justices: Prestige, Principles and Politics John P

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Indiana University Bloomington Maurer School of Law Maurer School of Law: Indiana University Digital Repository @ Maurer Law Articles by Maurer Faculty Faculty Scholarship 1941 The Appointment of Supreme Court Justices: Prestige, Principles and Politics John P. Frank Indiana University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub Part of the Courts Commons, and the Judges Commons Recommended Citation Frank, John P., "The Appointment of Supreme Court Justices: Prestige, Principles and Politics" (1941). Articles by Maurer Faculty. Paper 1856. http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub/1856 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by Maurer Faculty by an authorized administrator of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE APPOINTMENT OF SUPREME COURT JUSTICES: PRESTIGE, PRINCIPLES AND POLITICS* JOHN P. FRANK Hidden in musty obscurity behind the forbidding covers of three hundred and more volumes of court reports, the Justices of the United States Supreme Court seldom emerge into public view. Deaths and retirements, new appointments, and occasional opinions attract fleeting attention; all else is unnoticed. But to the political scientist, to the historian, and, above all, to the lawyer, the Supreme Court is an object of vital concern. To the political scientist, the Court matters because it is the chief juggler in maintaining the Balance of Powers. To the historian, the Court matters because of its tre- mendous influence on the policies of federal and state governments. -

H. Doc. 108-222

OFFICERS OF THE EXECUTIVE BRANCH OF THE GOVERNMENT [ 1 ] EXPLANATORY NOTE A Cabinet officer is not appointed for a fixed term and does not necessarily go out of office with the President who made the appointment. While it is customary to tender one’s resignation at the time a change of administration takes place, officers remain formally at the head of their department until a successor is appointed. Subordinates acting temporarily as heads of departments are not con- sidered Cabinet officers, and in the earlier period of the Nation’s history not all Cabinet officers were heads of executive departments. The names of all those exercising the duties and bearing the respon- sibilities of the executive departments, together with the period of service, are incorporated in the lists that follow. The dates immediately following the names of executive officers are those upon which commis- sions were issued, unless otherwise specifically noted. Where periods of time are indicated by dates as, for instance, March 4, 1793, to March 3, 1797, both such dates are included as portions of the time period. On occasions when there was a vacancy in the Vice Presidency, the President pro tem- pore is listed as the presiding officer of the Senate. The Twentieth Amendment to the Constitution (effective Oct. 15, 1933) changed the terms of the President and Vice President to end at noon on the 20th day of January and the terms of Senators and Representatives to end at noon on the 3d day of January when the terms of their successors shall begin. [ 2 ] EXECUTIVE OFFICERS, 1789–2005 First Administration of GEORGE WASHINGTON APRIL 30, 1789, TO MARCH 3, 1793 PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—GEORGE WASHINGTON, of Virginia. -

Bamzai 93 Notre Dame L. Rev. 1501.Pdf

+(,1 2 1/,1( Citation: Aditya Bamzai, The Attorney General and Early Appointments Clause Practice, 93 Notre Dame L. Rev. 1501 (2018) Provided by: University of Virginia Law Library Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Fri Sep 7 10:14:19 2018 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at https://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: Copyright Information Use QR Code reader to send PDF to your smartphone or tablet device THE ATTORNEY GENERAL AND EARLY APPOINTMENTS CLAUSE PRACTICE Aditya Bamzai* INTRODUCTION Among the structural provisions of the Constitution are a series of rules specifying the method by which the federal government will be staffed. One of those rules, contained in what is known as the Appointments Clause, estab- lishes the procedures for appointing "all ... Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not .. otherwise provided for" in the Constitu- tion-requiring one mechanism (presidential appointment and senate con- firmation) for "principal" officers and permitting a set of alternatives (appointment by the "President alone," the "Courts of Law," or the "Heads of Departments") for "officers" who are considered "inferior."' The Clause has traditionally been understood to require these appointment procedures for a subset of federal government employees who meet some constitutional threshold that establishes their status as "officers," rather than for all federal employees.2 In light of that understanding, the Clause naturally raises a question about the precise boundary between constitutional "officers" and other federal "employees"-a question that has recently been the subject of substantial litigation and extensive treatment within the executive branch 3 and the scholarly literature. -

Department of Justice Journal of Federal Law and Practice

DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE JOURNAL OF FEDERAL LAW AND PRACTICE Volume 68 September 2020 Number 4 Acting Director Corey F. Ellis Editor-in-Chief Christian A. Fisanick Managing Editor E. Addison Gantt Associate Editors Gurbani Saini Philip Schneider Law Clerks Joshua Garlick Mary Harriet Moore United States The Department of Justice Journal of Department of Justice Federal Law and Practice is published by Executive Office for the Executive Office for United States United States Attorneys Attorneys Washington, DC 20530 Office of Legal Education Contributors’ opinions and 1620 Pendleton Street statements should not be Columbia, SC 29201 considered an endorsement by Cite as: EOUSA for any policy, 68 DOJ J. FED. L. & PRAC., no. 4, 2020. program, or service. Internet Address: The Department of Justice Journal https://www.justice.gov/usao/resources/ of Federal Law and Practice is journal-of-federal-law-and-practice published pursuant to 28 C.F.R. § 0.22(b). Page Intentionally Left Blank For K. Tate Chambers As a former editor-in-chief (2016–2019), Tate Chambers helped make the Journal what it is today. His work transformed it from a bi-monthly, magazine-style publication to a professional journal that rivals the best publications by the top law schools. In doing so, Tate helped disseminate critical information to the field and helped line AUSAs preform at their highest. Tate served the Department for over 30 years, taking on several assignments to make the Department a better place, and his work created a lasting legacy. This issue of the Journal, focused on providing insight for new AUSAs, is dedicated to Tate.