Fiction Fix 12 April Gray Wilder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manicure Catalogue

CATALOGO RBB MANICURE EXTRA LINE Articles carefully produced and checked by our artisans, forged with the best materials in the sector to satisfy every professionist. MANICURE SCISSORS 244 C Cuticle scissors curved 244 R Cuticle scissors straight 246 C Nail scissors curved 246 R Nail scissors straight 244 LC Cuticle scissors curved pointed tips 244 LR Cuticle scissors straight pointed tips 245 LC Nail scissors curved pointed tips 244 246 244L 245L 310/1/3,5R Cuticle scissors straight 9 cm 310/1/3,5C Cuticle scissors curved 9 cm 310/1/4R Cuticle scissors straight 10 cm 310/1/4C Cuticle scissors curved 10 cm 225/1/4 Moustache scissors 320/1/4 Ear & nose scissors 326/1/4 326/1/4 Toenail scissors 225/1/4 320/1/4 310 244L CICOGNA SCISSORS 244L 235/1/3,5 “Cicogna” scissors 9 cm 235/1/4,5 “Cicogna” scissors 11 cm 235/1 TWEEZERS 470 Fantasy professional tweezers 471 Color professional tweezers 471 6472 Professional tweezers 470 6472 NIPPERS 322/I/4 mm3 Cuticle nippers blade 3 mm 322/I/4 mm5 Cuticle nippers blade 5 mm 322/I/4 mm7 Cuticle nippers blade 7 mm 322/I/4 mm9 Cuticle nippers blade 9 mm 322/P/4 Cuticle nippers 10 cm 324/P/4 Nail nippers 10 cm 324/P/4,5 Nail nippers 11 cm 324/P/5 Nail nippers 12 cm 322/I/4 322/P/4 324/P 325/BO/5,5 Toenail nippers 14 cm 325/BI/5,5 Nail nippers 14 cm 325/X/4,5 Nail nippers pointed 11 cm 325/X/5 Nail nippers pointed 12 cm 1 325/BO/5,5 325/BI/5,5 325/X CATALOGO RBB MANICURE INOX EXTRA LINE Line produced with stainless steel, which allows complete sterilization, completed with the highest quality professional accessories. -

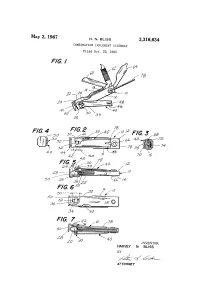

May 2, 1967 H, N. BLISS 3,316,634 COMBINATION IMPLEMENT AS SEMBLY Filed Oct

May 2, 1967 H, N. BLISS 3,316,634 COMBINATION IMPLEMENT AS SEMBLY Filed Oct. 22, 1965 INVENTOR. HARVEY N. BLSS BY A 77OAWEY 3,316,634 United States Patent Office Patented May 2, 1967 2 mounted thereon which extends generally longitudinally COMBINATION i?3,316,634 a PLEENT ASSEMBLY of the side wall portions and is pivotable into operative Harvey N. Bliss, Windsor, Conta, assigner to The Brition position with its free end spaced above the side wall por Corporation, Newington, Coan, a corporation of Con tions for biasing the unconnected lengths into engage nectic at ment by the abutting of the clipper jaw elements. A Filed Oct. 22, 1965, Ser. No. 501,482 pivot member is provided adjacent the connected side 2 Claims. (CE. 30-43) wall end of the casing and has at least one blade member The present invention relates to a combination imple pivotably mounted thereon which is receivable in the ment assembly, and more particularly to a combination casing for rotation from a closed position disposed within implement assembly providing a nail clipper and a plu 0 the casing to an open position generally aligned with the rality of blade-like implements. elongated axis of the casing. Thus, in the present invention, the casing is integrally Many pocket knives provide a plurality of blade-like formed of resiliently deflectable sheet metal and provides implements including a knife, nail file, screwdriver, a a pair of spaced apart side wall portions which provide bottle opener, and like members as individual blade mem 5 both unconnected lengths thereof with nail clipper jaw bers or in the form of combination blade members ca elements on end thereof and a housing for blade-like im pable of several functions. -

PO Box 101 Banora Point, NSW Australia 2486 NAIL SNAIL

Media Contact Contact Person: Julia Christie Contact Email: [email protected] , [email protected] Phone Number: 0421860045 Website: www.nail-snail.com Postal Address: PO Box 101 Banora Point, NSW Australia 2486 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NAIL SNAIL: THE SOLUTION TO THE AGE-OLD PROBLEM OF TRIMMING TINY NAILS THIS REVOLUTIONARY NEW 3-IN-1 BABY NAIL TRIMMER PROVIDES A SAFE, EASY AND QUICK OPTION FOR TRIMMING THE NAILS OF NEWBORNS, INFANTS AND CHILDREN. AUSTRALIAN FAMILY-RUN BUSINESS, CHRISTIE AND CHRISTIE, IS LAUNCHING A KICKSTARTER CAMPAIGN ON FEBRUARY 15 TO RAISE FUNDS FOR THE FIRST PRODUCTION RUN OF THIS INNOVATIVE NEW PRODUCT. February 15, 2017, Gold Coast, Australia: Today, Christie & Christie, an Australian, family owned company, is proud to announce the launch of their Kickstarter campaign for the Nail Snail, the first substantial change in nail clipper design for over a century. This product, which will change the face of child nail care, is designed to provide a safe, quick and easy method by which to trim the nails of newborns, babies, and children up to 5 years old. Mother of two, Julia Christie, who, after the birth of her first child, realized the enormity of this problem facing parents the world over, invented the Nails Snail. The spark of a new idea was followed by years of hard work, dedication, and much research and development. The Nail Snail is a multi-purpose 3-in-1 tool that allows easy fingernail and toenail trimming, nail filing and under nail cleaning. Features such as the easy grip handle, compact construction, and innovative ‘V’ shaped precision trimmer to allow multi directional cutting, make this product the best option for the care of babies’ nails. -

Nr Kat Artysta Tytuł Title Supplement Nośnik Liczba Nośników Data

nr kat artysta tytuł title nośnik liczba data supplement nośników premiery 9985841 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us black LP+CD LP / Longplay 2 2015-10-30 9985848 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us Ltd. Edition CD / Longplay 1 2015-10-30 88697636262 *NSYNC The Collection CD / Longplay 1 2010-02-01 88875025882 *NSYNC The Essential *NSYNC Essential Rebrand CD / Longplay 2 2014-11-11 88875143462 12 Cellisten der Hora Cero CD / Longplay 1 2016-06-10 88697919802 2CELLOSBerliner Phil 2CELLOS Three Language CD / Longplay 1 2011-07-04 88843087812 2CELLOS Celloverse Booklet Version CD / Longplay 1 2015-01-27 88875052342 2CELLOS Celloverse Deluxe Version CD / Longplay 2 2015-01-27 88725409442 2CELLOS In2ition CD / Longplay 1 2013-01-08 88883745419 2CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb DVD-V / Video 1 2013-11-05 88985349122 2CELLOS Score CD / Longplay 1 2017-03-17 0506582 65daysofstatic Wild Light CD / Longplay 1 2013-09-13 0506588 65daysofstatic Wild Light Ltd. Edition CD / Longplay 1 2013-09-13 88985330932 9ELECTRIC The Damaged Ones CD Digipak CD / Longplay 1 2016-07-15 82876535732 A Flock Of Seagulls The Best Of CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88883770552 A Great Big World Is There Anybody Out There? CD / Longplay 1 2014-01-28 88875138782 A Great Big World When the Morning Comes CD / Longplay 1 2015-11-13 82876535502 A Tribe Called Quest Midnight Marauders CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 82876535512 A Tribe Called Quest People's Instinctive Travels And CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88875157852 A Tribe Called Quest People'sThe Paths Instinctive Of Rhythm Travels and the CD / Longplay 1 2015-11-20 82876535492 A Tribe Called Quest ThePaths Low of RhythmEnd Theory (25th Anniversary CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88985377872 A Tribe Called Quest We got it from Here.. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,020,964 B2 Han Et Al

US007020964B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,020,964 B2 Han et al. (45) Date of Patent: Apr. 4, 2006 (54) NAIL CLIPPER AND NAIL CUTTER, LEVER 796,389 A 8/1905 Wright AND SUPPORTING SHAFT FOR THE SAME 806,037 A 11, 1905 Wilcox 1,085,569 A * 1/1914 Casse ............................ 30, 28 (76) Inventors: Jeong Sik Han, c/o BOCAS Inc., 62-7 2,477,782 A 8, 1949 Bassett ...................... 132,755 Ogeum-Dong, Songpa-Ku, Seoul (KR) 2,995,820 A 8, 1961 Pocoski ......................... 30, 28 3,042,047 A 7/1962 Plaskon ..................... 132,755 138-856; Gyoung Hee Kim, c/o 3,555,675 A 1/1971 Jurena ........................... 30, 28 BOCAS Inc., 62-7 Ogeum-Dong, 5,226,849 A 7/1993 Johnson ......................... 30, 28 Songpa-Ku, Seoul (KR) 138-856 5.488,772 A 2f1996 Dababneh et al. 5,832,610 A * 11/1998 Chaplick ....................... 30, 28 (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 5,870,826 A 2, 1999 Lewan .......................... 30, 28 patent is extended or adjusted under 35 6,173,497 B1 1/2001 Domenge U.S.C. 154(b) by 52 days. 6,523,545 B1* 2/2003 Rende ....................... 132,755 2002/0092.172 A1* 7/2002 Park .............................. 30, 28 (21) Appl. No.: 10/730,910 FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS (22) Filed: Dec. 10, 2003 JP 57-27.204 2, 1982 JP 11-169227 6, 1999 (65) Prior Publication Data JP 2002-142853 5, 2002 WO O2/398.44 5, 2002 US 2004/O 111893 A1 Jun. 17, 2004 WO O2/O67720 9, 2002 (30) Foreign Application Priority Data * cited by examiner Dec. -

Levers Around the House Page 48

Grade 7 Page 47 CIBL Levers Around NC Essential the House Standard 7.P.2.4 Throughout the guide teaching tips are in red. Overview Over a few class periods, this three-part activity introduces students to levers and the concept of mechanical advantage. On the first day, before learning about levers, students are presented with nail clipper bases without the lever attached, are asked to use it to cut a nail, and then to draw the tool as-is, labeling the drawing to show where force is applied and where it is used. Next, they receive the clipper lever, assemble it, use it, and learn that the job is easier. They then redraw the clippers with the lever, again showing where force is applied and where it is used. After this exploration, students go through similar steps with scissors. On the next day, students again have clippers, scissors, and their drawings. This time they identify the levers in these objects, measure distances that both ends of the lever travel, and develop some ideas about how the levers might make things easier, including the concept of work. Objectives •Students can explain that levers make it possible to apply more force. •Students can demonstrate the mechanical advantage (increased efficiency) of a lever, using less force over a greater distance to produce more force over a shorter distance. NC Essential 7.P.2.4 Explain how simple machines such as inclined planes, pulleys, levers Science Standards and wheels and axles are used to create mechanical advantage and increase efficiency. Science Background This activity explores ways to do some simple things more easily. -

Edible Wild Plants Of

table of contents Title: Edible wild plants of eastern North America Author: Fernald, Merritt Lyndon, 1873- Print Source: Edible wild plants of eastern North America Fernald, Merritt Lyndon, 1873- Idlewild Press, Cornwall-on-Hudson, N.Y. : [c1943] First Page Page i view page image ALBERT R. MANN LIBRARY NEW YORKSTATE COLLEGES. ~ OF AGRICULTURE AND HOME ECONOMICS AT CORNELL UNIVERSITY Front Matter Page ii view page image Page iii view page image EDIBLE WILD PLANTS of EASTERN NORTH AMERICA Page vi view page image 1 An Illustrated Guide to all Edible Flower- ing Plants and Ferns, and some of the more important Mushrooms, Seaweeds and Lich- ens growing wild in the region east of the Great Plains and Hudson Bay and north of Peninsular Florida Page vii view page image INTRODUCTION NEARLY EVERY ONE has a certain amount of the pagan or gypsy in his nature and occasionally finds satisfaction in living for a time as a primitive man. Among the primi- tive instincts are the fondness for experimenting with un- familiar foods and the desire to be independent of the conventional sources of supply. All campers and lovers of out-of-door life delight to discover some new fruit or herb which it is safe to eat, and in actual camping it is often highly important to be able to recognize and secure fresh vegetables for the camp-diet; while in emergency the ready recognition of possible wild foods might save life. In these days, furthermore, when thoughtful people are wondering about the food-supply of the present and future generations, it is not amiss to assemble what is known of the now neglected but readily available vege- table-foods, some of which may yet come to be of real economic importance. -

Studies in the Sources of J.R.R. Tolkien's the Lord of the Rings

.-- . .,l,.. .I~ i . ,. s._ .i. -_. _..-..e.. _ . (3 f Preface i In the Spring of 1968 while I was studying the Old English poem Beowulf with Dr. Rudolph Bambas, my colleague and classmate Judith Moore suggested that I might enjoy reading a new work by J:R.R. Tolkien, known to us as the editor of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and the author of that seminal article -- “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics.” The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings delighted me that summer. In the fall, at the urging of another colleague, I enrolled in the Old Norse seminar. That conjunction of events proved to be the beginning of a lifelong study of Northern literature and its contributions to the cauldron of story which produced The Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit, The Silmarillion, and The Unfinished Tales. The first version of this study became my doctoral dissertation -- “Studies in the Sources of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings.“1 Throughout the years that followed while I was either teaching college English or working as a librarian, I have continued my research. The original study was based on about twenty-five sagas; that number has been tripled. Christopher Tolkien’s careful publication of The Silmarillion, The Unfinished Tales, and six volumes of The Historv of Middle-earth has greatlyreatly expanded the canon available for scholarly study. Humphrey Carpenter’s authorized biography has also been helpful. However, the Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien have produced both the . greatest joy and the greatest terror. -

Przegląd Humanistyczny 2015/4 (451)

PrzegladHum_4_2015 4/7/16 8:38 AM Page 1 Ceny „Przeglądu Humanistycznego” w roku 2015: 4 Prenumerata roczna (4 numery) – 120,00 zł, Prenumerata półroczna (2 numery) – 60,00 zł, 2015 Opłata za pojedynczy numer – 30,00 zł. PRZEGLĄD Zamówienia na pojedyncze egzemplarze prosimy kierować na adres: [email protected] Zamówienia na prenumeratę „Przeglądu Humanistycznego” przyjmują: PRZEGL HUMANISTYCZNY RUCH S.A. Zamówienia na prenumeratę w wersji papierowej i na e-wydania można składać KWARTALNIK • ROK LIX / 2015 • NR 4 (451) bezpośrednio na stronie www.prenumerata.ruch.com.pl Ewentualne pytania prosimy kierować na adres e-mail: [email protected] lub kontaktując się z Centrum Obsługi Klienta „RUCH” pod numerami: Ą 22 693 70 00 lub 801 800 803 – czynne w dni robocze w godzinach 7–17. D HUMANISTYCZNY O TERYTORIACH, GRANICACH I MAPACH Koszt połączenia wg taryfy operatora. PISZĄ M.IN.: F. KROBB: From Track to Territory: German Cartographic KOLPORTER SA, ul. Kolberga 11, 25-620 Kielce Penetration of Africa, c. 1860–1900 Y. SCHWARTZ: But at Night, at Night, I still Dream in Spanish. GARMOND PRESS SA, ul. Sienna 5, 31-041 Kraków The Map of the Imagination of Israeli Literature: The South American Province Subscription orders for all magazines published in Poland available through B. KALNAČS: Territories, Memories, and Colonial Difference: the locał press distributors or directly through the Foreign Trade Enterprise A Comparative Insight into Late Nineteenth-Century Latvian ARS POLONA SA, ul. Obrońców 25, 03-933 Warszawa, Poland. BANK and German Literature HANDLOWY SA, Oddział w Warszawie, PL 02 1030 1016 0000 0000 0089 5001 J. -

Swiss Army Knives

Distributed in the United States by: Wenger NA 15 Corporate Drive Orangeburg NY 10962 Tel: 800-431-2996, 845-365-3500 Fax: 845-425-4700 (General Correspondence) 845-365-3743 (Orders only) www.WengerNA.com SWISS ARMY KNIVES 2007 New Product Introductions The Genuine Swiss Army Knife™ The Genuine Swiss Army Knife™ Item #883 EvoGrip 16 EVOGRIP EvoGrip 18 EVOGRIP INTRODUCING I Weight 2.6 oz. I Weight 3.1 oz. EVOGRIP 16811 16814 S S N N O O I I T T C C N N U U F F 4 5 1 The Evolution Series represented 1 – – S S T a dramatic and unique redesign of the T N N E E M M E venerable Swiss Army knife by employing a new, E L L P P M M I smart ergonomic handle. Now, Wenger is taking the I 0 1 1 next step in the progression of the Evolution 1 platform with EvoGrip. By adding rubber to the most critical areas of the handle, the knife’s safety, performance and functionality have been Actual size 3.25" Actual size 3.25" increased again. Ergonomic handles with rubber • 2.5" Blade • 2.4" Springless scissors with Ergonomic handles with rubber • 2.5" Blade • 2.75" Double-cut wood saw, serrated, self-sharpening design • Patented locking screwdriver, cap lifter, • 2.4" Springless scissors with serrated, self-sharpening design • Patented wire stripper • Can opener • Nail file, nail cleaner • Phillips® head locking screwdriver, cap lifter, wire stripper • Can opener • Nail file, nail screwdriver • Reamer, awl • Toothpick • Tweezers • Key ring cleaner • Phillips® head screwdriver • Reamer, awl • Toothpick • Tweezers • Key ring EvoGrip 10 EVOGRIP EvoGrip S54 EVOGRIP EvoGrip S557 EVOGRIP I 16810 Weight 1.9 oz. -

Victorinox SAK Directory VICTORINOX 1884 - 2021 MORE THAN 130 YEARS of EXPERIENCE and LIVED SWISS TRADITION

MAKERS OF THE ORIGINAL SWISS ARMY KNIFE | ESTABLISHED 1884 Victorinox SAK Directory VICTORINOX 1884 - 2021 MORE THAN 130 YEARS OF EXPERIENCE AND LIVED SWISS TRADITION The little red pocket knife, with Cross & Shield emblem in design and quality, but also in their ability to serve on the handle is an instantly recognisable symbol of as reliable companions on life’s adventures, both great our company. In a unique way, it conveys excellence and small. in Swiss crafts manship, and also the impressive Today, the full range of Victorinox knives is comprised expertise of more than 2,000 employees worldwide. of over 1,200 models. The range is presented in The principles by which we do business, are as two, separate catalogs: «Swiss Army Knives» and relevant today as they were in 1897 when our company «Household and Professional Knives». We are pleased founder, Karl Elsener, developed the «Original Swiss to offer this streamlined assortment, with our best, Army Knife»: functionality, innovation, iconic design and perhaps future classics. and uncompromising quality. Our commitment to these principles for more than 130 years has allowed Carl Elsener us to develop products that are not only extraordinary CEO Victorinox 6 10 12 SMALL POCKET KNIVES SWISS CARDS MEDIUM POCKET KNIVES 58 mm Companion 6 Classic 10 84 mm Original Swiss Army Knives, Small Models 12 INFORMATION 65 mm Companion 9 Lite 10 85 mm Evolution 14 Nailcare 11 91 mm Original Swiss Army Knives, Large Models 18 Quattro 11 93 mm Pioneer 26 26 27 33 34 SPORTS LARGE POCKET KNIVES SWISS TOOLS ACCESSORIES Golf Tool 26 111 mm Workman 28 Swiss Tool Spirit 31 Pouches 34 130 mm Ranger 28 Swiss Tool 32 Knife Sharpeners 35 PACKAGING There are two types of packaging for pocket knives: Standard packaging and blister packaging. -

Packing Ideas for Operation Christmas Child: Girls/Boys 10-14 Years

Packing Ideas for Operation Christmas Child: Girls/Boys 10-14 years: Do Not Include: Candy; toothpaste; used or damaged items; war-related items such as guns; knives; military figures; chocolate or food; fruit rolls or other fruit snacks; drink mixes (powdered or liquid); liquids or lotions; medications or vitamins; breakable items such as snow globes or glass containers; aerosol cans. A “WOW” Item: • Doll (consider including accessories such as doll clothes or a small doll bed.) • Deflated Soccer ball (Make sure to include a manual air pump so that the ball can be re-inflated.) • Stuffed animal • Toy truck or boat • An outfit of clothing to wear • Small musical instrument (such as a harmonica or woodwind recorder.) • Backpack Personal Care Items: • Comb/ Hairbrush • Washcloth • Bar soap (packaged and/or in a container) • Adhesive bandages (Colorful ones can help a child be more willing to wear a bandage. Do not include liquid antibiotic ointment.) • Reusable plastic containers: cup, water bottle, plate, bowl, blunt-edged utensils (Consider filling an empty container with non-liquid items such as hair bows, bracelets, sunglasses, or washcloths or maximize the space.) • Non-liquid lip balm • Flashlight (solar-powered or hand-crank; if battery operated, be sure to include extra batteries of the type needed) • Compact mirror • Nail clipper and file • Stick deodorant • Washable/reusable cloth menstrual pads School Suplies: • Pencils/Pens • Small manual pencil sharpener • Colored pencils/Crayons/Markers • Erasers • Pencil case • Notebooks/Blank