Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No. 40. the System of Lunar Craters, Quadrant Ii Alice P

NO. 40. THE SYSTEM OF LUNAR CRATERS, QUADRANT II by D. W. G. ARTHUR, ALICE P. AGNIERAY, RUTH A. HORVATH ,tl l C.A. WOOD AND C. R. CHAPMAN \_9 (_ /_) March 14, 1964 ABSTRACT The designation, diameter, position, central-peak information, and state of completeness arc listed for each discernible crater in the second lunar quadrant with a diameter exceeding 3.5 km. The catalog contains more than 2,000 items and is illustrated by a map in 11 sections. his Communication is the second part of The However, since we also have suppressed many Greek System of Lunar Craters, which is a catalog in letters used by these authorities, there was need for four parts of all craters recognizable with reasonable some care in the incorporation of new letters to certainty on photographs and having diameters avoid confusion. Accordingly, the Greek letters greater than 3.5 kilometers. Thus it is a continua- added by us are always different from those that tion of Comm. LPL No. 30 of September 1963. The have been suppressed. Observers who wish may use format is the same except for some minor changes the omitted symbols of Blagg and Miiller without to improve clarity and legibility. The information in fear of ambiguity. the text of Comm. LPL No. 30 therefore applies to The photographic coverage of the second quad- this Communication also. rant is by no means uniform in quality, and certain Some of the minor changes mentioned above phases are not well represented. Thus for small cra- have been introduced because of the particular ters in certain longitudes there are no good determi- nature of the second lunar quadrant, most of which nations of the diameters, and our values are little is covered by the dark areas Mare Imbrium and better than rough estimates. -

Feature of the Month – January 2016 Galilaei

A PUBLICATION OF THE LUNAR SECTION OF THE A.L.P.O. EDITED BY: Wayne Bailey [email protected] 17 Autumn Lane, Sewell, NJ 08080 RECENT BACK ISSUES: http://moon.scopesandscapes.com/tlo_back.html FEATURE OF THE MONTH – JANUARY 2016 GALILAEI Sketch and text by Robert H. Hays, Jr. - Worth, Illinois, USA October 26, 2015 03:32-03:58 UT, 15 cm refl, 170x, seeing 8-9/10 I sketched this crater and vicinity on the evening of Oct. 25/26, 2015 after the moon hid ZC 109. This was about 32 hours before full. Galilaei is a modest but very crisp crater in far western Oceanus Procellarum. It appears very symmetrical, but there is a faint strip of shadow protruding from its southern end. Galilaei A is the very similar but smaller crater north of Galilaei. The bright spot to the south is labeled Galilaei D on the Lunar Quadrant map. A tiny bit of shadow was glimpsed in this spot indicating a craterlet. Two more moderately bright spots are east of Galilaei. The western one of this pair showed a bit of shadow, much like Galilaei D, but the other one did not. Galilaei B is the shadow-filled crater to the west. This shadowing gave this crater a ring shape. This ring was thicker on its west side. Galilaei H is the small pit just west of B. A wide, low ridge extends to the southwest from Galilaei B, and a crisper peak is south of H. Galilaei B must be more recent than its attendant ridge since the crater's exterior shadow falls upon the ridge. -

00010853-Preview.Pdf

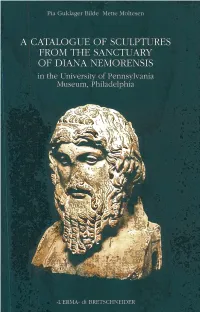

ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANIcI Supplemen turn XXIX A CATALOGUE OF SCULPTURES FROM THE SANCTUARY OF DIANA NEMORENSIS IN THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA MUSEUM, PHILADELPHIA A Catalogue of Sculptures from the Sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis in The University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia by Pia Guldager Bilde and Mette Moltesen <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER ROMAE MMII ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANIcI, SUPPL. XXIX Accademia di Danimarca - Via Omero, 18 - 00197 Rome - Italy Lay-out by the editors © 2002 <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER, Rome PUBLISHED WITH THE SUPPORT OF GRANTS FROM Knud Højgaards Fond Novo Nordisk Fonden University of Pennsylvania. Museum of archaeology and anthropology A catalogue of sculptures from the sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis in the University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia / by Pia Guldager Bilde and Mette Moltesen. - Roma: <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER , 2002. - 95 p. : ill. ; 30 cm. (Analecta Romana Instituti Danici. Supplementum ; 29) ISBN 88-8265-211-4 CDD 21. 731.4 1. Sculture in marmo - Collezioni 2. Filadelfia - University of Pennsylvania - Museum of archaeology and anthropology - Cataloghi I. Guldager Bilde, Pia II. Moltesen, Mette The journal ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANICI (ARID) publishes studies within the main range of the Academy's research activities: the arts and humanities, history and archaeology. Intending contributors should get in touch with the editors, who will supply a set of guide- lines and establish a deadline. A print of the article, accompanied y a disk containing the text should be sent to the editors, Accademia di Danimarca, 18 Via Omero, I - 00197 Roma, tel. +39 06 32 65 931, fax +39 06 32 22 717. -

Special Catalogue Milestones of Lunar Mapping and Photography Four Centuries of Selenography on the Occasion of the 50Th Anniversary of Apollo 11 Moon Landing

Special Catalogue Milestones of Lunar Mapping and Photography Four Centuries of Selenography On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 moon landing Please note: A specific item in this catalogue may be sold or is on hold if the provided link to our online inventory (by clicking on the blue-highlighted author name) doesn't work! Milestones of Science Books phone +49 (0) 177 – 2 41 0006 www.milestone-books.de [email protected] Member of ILAB and VDA Catalogue 07-2019 Copyright © 2019 Milestones of Science Books. All rights reserved Page 2 of 71 Authors in Chronological Order Author Year No. Author Year No. BIRT, William 1869 7 SCHEINER, Christoph 1614 72 PROCTOR, Richard 1873 66 WILKINS, John 1640 87 NASMYTH, James 1874 58, 59, 60, 61 SCHYRLEUS DE RHEITA, Anton 1645 77 NEISON, Edmund 1876 62, 63 HEVELIUS, Johannes 1647 29 LOHRMANN, Wilhelm 1878 42, 43, 44 RICCIOLI, Giambattista 1651 67 SCHMIDT, Johann 1878 75 GALILEI, Galileo 1653 22 WEINEK, Ladislaus 1885 84 KIRCHER, Athanasius 1660 31 PRINZ, Wilhelm 1894 65 CHERUBIN D'ORLEANS, Capuchin 1671 8 ELGER, Thomas Gwyn 1895 15 EIMMART, Georg Christoph 1696 14 FAUTH, Philipp 1895 17 KEILL, John 1718 30 KRIEGER, Johann 1898 33 BIANCHINI, Francesco 1728 6 LOEWY, Maurice 1899 39, 40 DOPPELMAYR, Johann Gabriel 1730 11 FRANZ, Julius Heinrich 1901 21 MAUPERTUIS, Pierre Louis 1741 50 PICKERING, William 1904 64 WOLFF, Christian von 1747 88 FAUTH, Philipp 1907 18 CLAIRAUT, Alexis-Claude 1765 9 GOODACRE, Walter 1910 23 MAYER, Johann Tobias 1770 51 KRIEGER, Johann 1912 34 SAVOY, Gaspare 1770 71 LE MORVAN, Charles 1914 37 EULER, Leonhard 1772 16 WEGENER, Alfred 1921 83 MAYER, Johann Tobias 1775 52 GOODACRE, Walter 1931 24 SCHRÖTER, Johann Hieronymus 1791 76 FAUTH, Philipp 1932 19 GRUITHUISEN, Franz von Paula 1825 25 WILKINS, Hugh Percy 1937 86 LOHRMANN, Wilhelm Gotthelf 1824 41 USSR ACADEMY 1959 1 BEER, Wilhelm 1834 4 ARTHUR, David 1960 3 BEER, Wilhelm 1837 5 HACKMAN, Robert 1960 27 MÄDLER, Johann Heinrich 1837 49 KUIPER Gerard P. -

Geochemicaljournal,Vol.28,Pp. 173To 184,1994 C H

GeochemicalJournal,Vol.28,pp. 173to 184,1994 C h em ic al c h a r acters of cr ater la k es in th e A z o res a n d Italy: th e a n o m aly o f L a k e A lb a n o M ARlNO M ARTlNl,1 L UCIANO GIANNINl,1 FRANCO PRATI,1 FRANCO TASSI,l B RUNO CAPACCIONl2 and PAOLO IOZZELL13 IDepartm ent ofEarth Sciences,U niversity ofFlorence, 50121 Florence,Italy 2lnstitute ofV olcanology and G eochemistry, University ofUrbino, 61029 Urbino,Italy 3Departm ent ofPharm aceutical Sciences, University ofFlorence,50121 Florence,Italy (Received April23, 1993,・Accepted January 10, 1994) Investigations have been carried out on craterlakesin areas ofrecent volcanism in the A zores and in Italy, with the aim of detecting possible evidence of residual anom alies associated with past volcanic activities;data from craterlakes ofCam eroon have been considered for com parison. A m ong the physical- chem ical ch aracters taken into account, the increases of tem perature, am m onium and dissolved carbon dioxide with depth are interp reted as providing inform ation aboutthe contribution of endogene fluidsto the lake w ater budgets. The greater extent of such evidence at Lakes M onoun and N yos (Cam eroon) appears associated withthe disastersthatoccurred there duringthe lastdecade;som e sim ilarities observed atLake Albano (Italy)suggesta potentialinstability also forthis craterlake. parison. W ith reference to the data collected so INTRODUCT ION far and considering the possibility that the actual Crater lakes in active volcanic system s have chem ical characters ofcrater lakes are influenced been investigated with reference to change s oc- by residualtherm al anom alies in the hosting vol- curing in w ater chem istry in response to different canic system s, an effort has been m ade to verify stages of activity, and interesting inform ation is w hether and to w hat extent these anom alies can available about R u apehu (Giggenbach, 1974), be revealed by sim ple observations. -

THE MARS ULTOR COINS of C. 19-16 BC

UNIWERSYTET ZIELONOGÓRSKI IN GREMIUM 9/2015 Studia nad Historią, Kulturą i Polityką s . 7-30 Victoria Győri King’s College, London THE MARS ULTOR COINS OF C. 19-16 BC In 42 BC Augustus vowed to build a temple of Mars if he were victorious in aveng- ing the assassination of his adoptive father Julius Caesar1 . While ultio on Brutus and Cassius was a well-grounded theme in Roman society at large and was the principal slogan of Augustus and the Caesarians before and after the Battle of Philippi, the vow remained unfulfilled until 20 BC2 . In 20 BC, Augustus renewed his vow to Mars Ultor when Roman standards lost to the Parthians in 53, 40, and 36 BC were recovered by diplomatic negotiations . The temple of Mars Ultor then took on a new role; it hon- oured Rome’s ultio exacted from the Parthians . Parthia had been depicted as a prime foe ever since Crassus’ defeat at Carrhae in 53 BC . Before his death in 44 BC, Caesar planned a Parthian campaign3 . In 40 BC L . Decidius Saxa was defeated when Parthian forces invaded Roman Syria . In 36 BC Antony’s Parthian campaign was in the end unsuccessful4 . Indeed, the Forum Temple of Mars Ultor was not dedicated until 2 BC when Augustus received the title of Pater Patriae and when Gaius departed to the East to turn the diplomatic settlement of 20 BC into a military victory . Nevertheless, Augustus made his Parthian success of 20 BC the centre of a grand “propagandistic” programme, the principal theme of his new forum, and the reason for renewing his vow to build a temple to Mars Ultor . -

La Latinità Di Ariccia E La Grecità Di Nemi. Istituzioni Civili E Religiose a Confronto

ANNA PASQUALINI La latinità di Ariccia e la grecità di Nemi. Istituzioni civili e religiose a confronto Il titolo del mio intervento è solo apparentemente contraddittorio. Esso è volto a mettere in relazione due contesti sociali tanto vicini nello spazio quanto distanti per impianto culturale e per funzioni politiche: la città di Ariccia e il lucus Dianius. Del bosco sacro a Diana e della selva che lo circonda si è scritto moltissimo soprattutto da quando esso costituì il fulcro di un’opera straordinaria per ricchezza ed originalità quale quella di Sir James Frazer1 Su Ariccia, invece, come comunità cittadina e sulle sue istituzioni politiche e religiose non si è riflettuto abbastanza2 e, in particolare, queste ultime non sono state messe sufficientemente in relazione con il santuario nemorense. Cercherò, quindi, di svolgere qualche considerazione nella speranza di fornire un piccolo contributo alla definizione degli intricati problemi del territorio aricino. Ariccia, come comunità politica, appare nelle fonti letterarie all’epoca del secondo Tarquinio, il tiranno per eccellenza, spregiatore del Senato e del popolo3. Al Superbo viene attribuita una forte vocazione al controllo politico del Lazio attraverso un’accorta rete di alleanze con i maggiorenti del Lazio, primo fra tutti il più eminente di essi, e cioè Ottavio Mamilio di Tuscolo, che è anche suo genero (Livio I 49); è ancora Tarquinio che, secondo le fonti (Livio I 50), indirizza la politica dei Latini convocando i federati in assemblea presso il lucus sacro a Ferentina4. La scelta del luogo non è casuale. Il bosco sacro è stato localizzato nel territorio di Ariccia, ma esso viene considerato idealmente collegato con il Monte Albano, cioè con il centro sacrale dei Latini, 1 La prima edizione dell’opera, The Golden Bough, risale al 1890. -

Newsletter Nov 2011

imperi nuntivs The newsletter of Legion Ireland --- The Roman Military Society of Ireland In This Issue • New Group Logo • Festival of Saturnalia • Roman Festivals • The Emperors - AD69 - AD138 • Beautifying Your Hamata • Group Events and Projects • Roman Coins AD69 - AD81 • Roundup of 2011 Events November 2011 IMPERI NUNTIUS The newsletter of Legion Ireland - The Roman Military Society of Ireland November 2011 From the editor... Another month another newsletter! This month’s newsletter kind grew out of control so please bring a pillow as you’ll probably fall asleep while reading. Anyway I hope you enjoy this months eclectic mix of articles and info. Change Of Logo... We have changed our logo! Our previous logo was based on an eagle from the back of an Italian Mus- solini era coin. The new logo is based on the leaping boar image depicted on the antefix found at Chester. Two versions exist. The first is for a white back- ground and the second for black or a dark back- ground. For our logo we have framed the boar in a victory wreath with a purple ribbon. We tried various colour ribbons but purple worked out best - red made it look like a Christmas wreath! I have sent these logo’s to a garment manufacturer in the UK and should have prices back shortly for group jackets, sweat shirts and polo shirts. Roof antefix with leaping boar The newsletter of Legion Ireland - The Roman Military Society of Ireland. Page 2 Imperi Nuntius - Winter 2011 The newsletter of Legion Ireland - The Roman Military Society of Ireland. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Livy's Early History of Rome: the Horatii & Curiatii

Livy’s Early History of Rome: The Horatii & Curiatii (Book 1.24-26) Mary Sarah Schmidt University of Georgia Summer Institute 2016 [1] The Horatii and Curiatii This project is meant to highlight the story of the Horatii and Curiatii in Rome’s early history as told by Livy. It is intended for use with a Latin class that has learned the majority of their Latin grammar and has knowledge of Rome’s history surrounding Julius Caesar, the civil wars, and the rise of Augustus. The Latin text may be used alone or with the English text of preceding chapters in order to introduce and/or review the early history of Rome. This project can be used in many ways. It may be an opportunity to introduce a new Latin author to students or as a supplement to a history unit. The Latin text may be used on its own with an historical introduction provided by the instructor or the students may read and study the events leading up to the battle of the Horatii and Curiatii as told by Livy. Ideally, the students will read the preceding chapters, noting Livy’s intention of highlighting historical figures whose actions merit imitation or avoidance. This will allow students to develop an understanding of what, according to Livy and his contemporaries, constituted a morally good or bad Roman. Upon reaching the story of the Horatii and Curiatii, not only will students gain practice and understanding of Livy’s Latin literary style, but they will also be faced with the morally confusing Horatius. -

Stories from the Early Years of Rome Latin 1 Project- 5Th 6Wks – NO LATE!!!!

Stories from the Early Years of Rome Latin 1 project- 5th 6wks – NO LATE!!!! The object of this project is to learn about the founding of Rome and stories from its early history. We will begin with the story of the Trojan war and Aeneas’s journey and end with the over throw of the kings of Rome and the early parts of the Roman republic. Section 1 - The Research and Sources– ____________________________ 1. You will have a topic to research from "the list" below. You will add your info to a wiki page you create for your topic. 2. You will need to have your wiki page completed for me to check by the date above. 3. Include your sources, properly formatted [MLA style], at the bottom of your wiki page. You must have at least 3 separate sources. Some of the topics have audio clips that can be used as one of your sources, but you must have other sources. 4. You will need to read Livy’s “ab urbe condita” [“From The Founding of the City”] in translation to get the best parts of the story. Some of you can listen to the audio files, but not all stories are there. I have linked several sources on our DISD Latin page. Section 2 – Illustration of Your Topic Presentations – ___________________ 5. Your final product will be a comic strip, comic book, or movie about the story you’ve chosen to research. [Yes, you may put your drawings on a ppt, but it should not have the whole story typed out on some slides. -

The Religious World of Quintus Aurelius Symmachus

The Religious World of Quintus Aurelius Symmachus ‘A thesis submitted to the University of Wales Trinity Saint David in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy’ 2016 Jillian Mitchell For Michael – and in memory of my father Kenneth who started it all Abstract for PhD Thesis in Classics The Religious World of Quintus Aurelius Symmachus This thesis explores the last decades of legal paganism in the Roman Empire of the second half of the fourth century CE through the eyes of Symmachus, orator, senator and one of the most prominent of the pagans of this period living in Rome. It is a religious biography of Symmachus himself, but it also considers him as a representative of the group of aristocratic pagans who still adhered to the traditional cults of Rome at a time when the influence of Christianity was becoming ever stronger, the court was firmly Christian and the aristocracy was converting in increasingly greater numbers. Symmachus, though long known as a representative of this group, has only very recently been investigated thoroughly. Traditionally he was regarded as a follower of the ancient cults only for show rather than because of genuine religious beliefs. I challenge this view and attempt in the thesis to establish what were his religious feelings. Symmachus has left us a tremendous primary resource of over nine hundred of his personal and official letters, most of which have never been translated into English. These letters are the core material for my work. I have translated into English some of his letters for the first time.