The Path Less Taken: the Intersection of Narratives and the Icelandic Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oaklands School Geography Department - Iceland Trip 2019

Oaklands School Geography Department - Iceland Trip 2019 Skogafoss Waterfall Name: __________________________________ Tutor Group: _____________________________ 1 Part A: Where is Iceland? Iceland is an island formerly belonging to Denmark. It has been a Republic since 1944 and is found in the middle of the North Atlantic Ocean. We will fly to Keflavik and stay near Hvolsvollur in the SW of the island. The map above is an enlargement of the box drawn on the map of Iceland below left. Map area on next Clearly, we are only visiting a small section of page the island, but in this small area you will be blown away by what you will see. Perhaps your visit to the island will prompt you to come back to explore further in the future? 2 Part B: History of Iceland Iceland is only about 20 million years old! It was formed by a series of volcanic eruptions at the Mid- Atlantic ridge. In fact the plume of magma called the Iceland ‘Hot Spot’ is responsible for its continued existence and almost continuous volcanic activity. Exact dates for first human occupancy is uncertain, but the accepted date is 874 for the first permanent settlers from Scandinavia. They settled near Reykjavik (which means ‘smokey cove’ – due to the Geothermal heat). Settlers continued to come from Norway, Scotland and Ireland. The first parliament was held at Thingvellir (pictured right), where chieftains met and agreed laws and rules for the country. The country converted to Christianity in the 11th Century, but pagan worship was tolerated if it was in secret. Civil war followed and the end result was that Iceland accepted Norwegian sovereignty and were ruled by the Norwegian kings. -

Landyacht Island 2016 V20160706

LandYacht Island 2016 V20160706 Abschnitt Seydisfjördur nach Reykjavik: Grundsätzlich kann man nach der Ankunft auf Island Richtung Süden oder Norden fahren. Wir empfehlen, nach Süden zu starten. So kann man vor der späteren Rückreise die Zeit bis zur Fährabfahrt am attraktiven Myvatn-See abpuffern und man ist früh in der Saison an unserer Topattraktion Nr.1 Jökulsarlon, der berühmten Gletscherbucht mit vielen treibenden Eisbergen. Bei unserem zweiten Besuch nur drei Wochen später (Ende Mai) waren etwa 2 Drittel weniger Eisberge zu sehen und am schwarzen Lavastrand waren gar keine Eiskolosse mehr zu finden. Auch haben wir nur beim ersten Mal zahlreiche Robben entdeckt. Eine detaillierte Reisebeschreibung ist für die ersten 800km gar nicht nötig, alle Attraktionen liegen links oder rechts direkt an der Ringstrasse und sind leicht zu finden. Es gibt sehr, sehr viele herrliche Naturschauplätze, die in den Reiseführern gut beschrieben sind. Wir fanden Cap Dyrholaey, die Wasserfälle Skogafoss, Seljalandfoss und den Svartifoss mit dem Gletscher Skaftafell besonders schön. Wenig beschrieben, aber traumhaft schön waren der Fjadrargljufur Canyon, das Wrack einer vor 50 Jahren notgelandeten DC3 am schwarzen Lavastrand, unser geheimer Stellplatz am Gluggafoss und der Urridafoss (siehe Koordinaten). Alleine für diesen Reiseabschnitt hatten wir 14 Tage Zeit und sie wurden mit vielen eindrucksvollen Ausblicken, Fotomotiven und Panoramen belohnt. Schnell begreift man bei der Fahrt, dass der gigantische Gletscher Vätnajökull ein Lebensspender für ganz Island ist: an fast jedem kleineren Wasserfall findet sich eine Farm, für Trinkwasser ist dann gesorgt, Strom kann generiert werden und es fehlt nur noch eine Erdbohrung für kostenlose Wärme; schon beginnt die Tierhaltung oder der Lebensmittelanbau. -

Unterwegs Mit Dem Reisemobil Auf Der Insel Der Vulkane Und Geysire

REISETIPP I sland? Wo liegt das denn? Ziemlich weit weg, denn die Insel ist nur per Fähre in ca. 48 Stunden Überfahrt oder mit dem Flugzeug zu erreichen. Die größte Vulkaninsel der Erde ist mit rund 103.000 km�nach dem Vereinigten Königreich der flächenmäßig zweitgrößte Inselstaat Europas und liegt knapp südlich des nördlichen Polarkreises. Bekannt ist Island für seinen unaussprechlichen Vulkan »Eyjafjallajökull«, gewaltige Wasserfälle und Geysire, beein- druckende Lavalandschaften, natürliche Hot Pools und seit der EM 2016 natürlich auch durch seine Fußballmannschaft. Marion und Sören Rehmann waren insgesamt 68 Tage während drei unterschiedlichen Reisen auf der Insel mit dem Reisemobil unterwegs und haben ihre Reiseeindrücke und wertvolle Tipps für uns aufgeschrieben. Da es genug Material für fast ein ganzes Buch ist, haben wir seinen Bericht im Magazin etwas gekürzt - den ganzen Artikel, inklusive Rundreise Snaefellsness-Halbinsel, finden Interessierte auf der LandYachting-Homepage. DIE ISLANDREISE VON MARION UND SÖREN Wir waren auf unseren 3 Island-Reisen von April bis Juli unterwegs und haben das Land von winterlichen Temperatu- ren bis zum sonnigen Frühling kennengelernt. Grundsätzlich kann man nach der Ankunft im Hafen Seydif- jordur auf Island Richtung Süden oder Norden fahren. Wir empfehlen, nach Süden zu starten. So kann man vor der späteren Rückreise die Zeit bis zur Fährabfahrt am attrakti- Abenteuer ven Myvatn-See abpuffern und man ist früh in der Saison an Jökulsarlon, der berühmten Gletscherbucht mit vielen treibenden Eisbergen, in der man Anfang April noch zahlrei- che Robben entdecken kann. Eine detaillierte Reisebeschrei- bung ist für die ersten 800 km gar nicht nötig, da alle Attrak- Island tionen links oder rechts der Ringstraße liegen und leicht zu finden sind. -

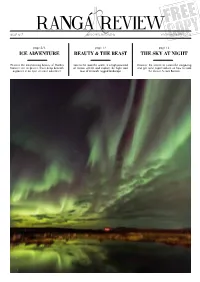

Rangá Review Issue 7

ISSUE N°7 SEASONAL MAGAZINE WWW.HOTELRANGA.IS page 2/3 page 13 page 15 ICE ADVENTURE BEAUTY & THE BEAST THE SKY AT NIGHT Witness the mesmerising beauty of Mother Take to the road this winter in a high powered Discover the secrets to successful stargazing Nature´s ice sculptures. Enter deep beneath all terrain vehicle and explore the highs and and get some expert advice on how to track a glacier in an epic ice cave adventure lows of Iceland’s rugged landscape the elusive Aurora Borealis ICE CAVE ADVENTURES The magic of the glaciers can never really be explained in words and images alone. To really understand the magnitude and marvel of a glacier and its ever-changing dynamics you really need to get up close and personal. Whether you decide to explore the empty magma chamber of a Hotel Rangá’s team recommends the following experiences: dormant volcano or discover the beauty of a crystal ice cave, guid- ed tours of lava and ice caves allow you to see for yourself why LAVA CAve RaufARHÓLSHELLIR Iceland is often referred to as the Land of Fire and Ice. Explore the magnificent lava tunnel Raufarhólshellir, one of the longest and best-known lava tubes in Iceland. A journey into Raufarhólshellir is a During the winter months the ice caves take on an entirely different unique experience and a great opportunity to witness the inner workings character as in the summer the sunlight makes the colours appear a of a volcanic eruption. Walk along the path of lava that flowed during the whiter shade. -

Yourflight Toadventure

32 Kjölur F336 25 To Djúpavogur and Seyðisfjörður Djúpavogur To To Akureyri 1 30 7 31 8 3 1 6 24 5 22 27 29 26 4 1 10 11 Useful telephone numbers 9 Road Conditions: 1777 23 2 Weather Information: 902-0600 Emergency Number: 112 To Keflavik Int. Airport 42 28 Special driving & traffic information Speed limits 21 The speed limit in urban areas is normally 50 km per hour. Outside towns, it is 90 13 km, on paved roads and 80 km on gravel roads. 15 17 Warning Domestic animals are often close to, or Check weather and road 14 even on, country roads. Drivers who hit conditions tel. 1777 12 animals may be required to pay for the or at www.road.is damage. 18 16 Travellers intending to explore out-of-the-way areas are encouraged to use the Travellers’ Reporting Service ICE-SAR, tel. 570-5900 20 19 Upplýsingamiðstöð Áhugaverður staður Bílferja Innanlandsflug Sundlaug seljalandsfoss. auglysing.new.pdf 1 29.05.15 09.56 Information Place of interest Ferry Domestic flights Geothermal Pool Glacier Jeeps – Ice & Adventure www.glacierjeeps.is [email protected] Published by South Iceland Marketing Office 2015 SELJALANDSFOSS Tel. (+354) 4781000 Yo ur flight Photos: Páll Jökull Pétursson, Þórir Niels Kjartansson, Ásborg Arnþórsdóttir, Arcanum, S to adventure Þorvarður Árnason, Katla Geopark, Glacierjeeps ehf, Laufey Guðmundsdóttir, Hótel Geysir, Visit Vatnajökull, Sigurdís Lilja Guðjónsdóttir, Sveinbjörn Jónsson, and others. Food & Beverage Adventure tours from road F985 with specially equipped 4WD jeeps to Jöklasel. eagleair.is Design and layout: Páll Jökull Pétursson Wool & Giftshop Skidoos, jeeps and glacier hiking tour on www.hrauneyjar.is Printing: Oddi hf Europe’s largest glacier Vatnajökull NATURE HIGHLIGHTS 7 Geysir 15 Þórsmörk valley 23 Eldgjá Geysir has lent its name to the English language in 51 km from Hvolsvöllur. -

Destination Management Plan Katla UNESCO Global Geopark DMP Katla UNESCO Global Geopark

Destination Management Plan Katla UNESCO Global Geopark DMP Katla UNESCO Global Geopark Emstrur Fjallabak 2 CONTENT 05 INTRODUCTION 13 THE PROCESS OF DEVELOPING A DESTINATION MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR KATLA UNESCO GLOBAL GEOPARK 17 KATLA UNESCO GLOBAL GEOPARK - A BRIEF OVERVIEW 31 CURRENT STATE OF LANDSCAPE AND TOURISM IN THE GEOPARK 57 CHALLENGES 77 LONG TERM VISION 97 RECREATIVE ENVIRONMENTAL FRAMEWORK 117 ACTION PLAN 225 CONCLUSION 233 APPENDICES DMP Katla UNESCO Global Geopark Vatnajökull glacier seen from the moss-covered lava field near the highway 4 INTRODUCTION DMP Katla UNESCO Global Geopark Gljúfrabúi waterfall tourists climbing the rocks near the waterfall Tourists taking selfies near Skógarfoss 6 DMP Katla UNESCO Global Geopark ver the past few decades, nature-based tourism has A flourishing tourism industry can provide various positive effects grown significantly worldwide, with a subsequent to a society and directly benefit the economic development of increase in the impact of tourism on delicate natural communities, both in major cities and in rural communities. landscapes (Newsome, Moore, and Dowling, 2013). However, it has also been shown that nature-based tourism can The increased popularity of nature-based tourism have significant negative impacts on Icelandic ecosystems such as Ois likely to immediately affect the planet’s most vulnerable overload, pollution, littering and trampling, causing deterioration ecosystems, especially in subarctic and arctic areas. Over the past and erosion (Gísladóttir, 2006; Ólafsdóttir and Runnström, 2013; few decades, arctic regions have become an increasingly popular Sæþórsdóttir, 2013, 2014). Also a significant increase in activities tourist destination. These regions offer stunning natural scenery like biking, horse riding, helicopter tourism (noise) and the use of and mainly attract tourists who are interested in experiencing 4WD cars and snowmobiles are likely to also have a detrimental nature and undertaking nature based activities. -

Behind the Scenes

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 411 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to your submissions, we always guarantee that your feed- back goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/ privacy. OUR READERS Alexis Averbuck My work on Iceland was a labour of love supported Many thanks to the travellers who used the last by many. Big thanks to Heimir Hansson (Westfjords), edition and wrote to us with helpful hints, useful Jón Björnsson (Hornstrandir), Dagný Jóhannsdóttir advice and interesting anecdotes: Anna Brunner & Jessica Brooke, Bart Streefkerk, Cliff & Helen Elsey, (Southwest), Kristján Guðmundsson (West), Rag- Daniel Crouch, Elena Kagi, Eyþór Jóvinsson, Fiorella nheiður Sylvía Kjartansdóttir (Reykjavík and every- Taddeo, Gudrun Stefansdottir, Helen Simpson, Ildiko where!), Einar Sæmundsen (Þingvellir) and Helga Lorik, Janire Echevarri, John Gerrard, John Malone, Garðarsdóttir (Laugavegurinn). -

Grönland · Färöer

ISLAND · GRÖNLAND · FÄRÖER 2020 Wir waren wieder für Sie unterwegs: Im September Vom 06.-12. Juli findet 2020 das Landsmót im Süden nahmen wir an einer Reisemesse auf den wunderschö- Islands, in Hella statt. Hierzu haben wir wieder schö- nen Färöer Inseln teil. Hier haben wir uns mit alten ne Kombinationen einer Reittour mit dem Landsmót- Bekannten, aber auch neuen interessanten Partnern Besuch zusammengestellt. Auch für Nichtreiter kann getroffen. Unser Kollege André hat sich auf eine der Besuch der isländischen Pferdemeisterschaften spannende Dienstreise rund um Island im Elektro- durchaus ein eindrucksvolles Erlebnis sein. Auto gemacht. Seinen Erfahrungsbericht finden Sie auf Seite 26. Wir freuen uns auf eine weitere, spannende Saison und auf die gemeinsame Reiseplanung sowohl mit Auch für die kommende Saison 2020 konnten wir die unseren treuen Stammkunden als auch mit allen Neu- Preise für unsere Islandreisen reduzieren. Die islän- kunden, denen wir Island sehr gerne näher bringen dische Krone ist weiterhin stabil, und unsere Partner möchten. Sjáumst! vor Ort haben ihre Preise nicht erhöht bzw. teilweise sogar merklich gesenkt. Auch für unsere Reisen nach Wedel, im November 2019 Grönland und auf die Färöer Inseln bleibt das Preis- Ihr Team von niveau gleich. Letztere erfreuen sich immer größerer ISLAND Erlebnisreisen Beliebtheit, so dass wir eine Gruppenreise mit ins Programm aufgenommen haben. Unser schönes Island Ihr Island-Erlebnisteam Wir als Island-Enthusiasten stellen uns vor: Am liebsten sind wir selbst dort, oder auch in Grönland oder den Färöer Inseln unterwegs; zusammen bringen wir es auf über 100 Island-, ein gutes Dutzend Grönland- und ein halbes Dutzend Färöer-Reisen. Einige von uns haben auch längere Zeit in Island oder Grönland gelebt, gearbeitet oder studiert. -

20/20 Sóknaráætlun

Stöðuskýrsla Suðursvæðis Töluleg samantekt Mars 2010 Stöðuskýrsla Suðursvæðis Tekið saman af Inngangur Ágæti viðtakandi, Þú hefur verið valin(n) til að taka þátt í Þjóðfundi á Suðursvæði sem haldinn verður laugardaginn 6. mars næstkomandi. Í þessari samantekt er ýmis opinber fróðleikur um Suðursvæði sem getur nýst vel í þeirri vinnu sem framundan er. Í Sóknaráætlun 20/20 er markmiðið að skapa nýja sókn í atvinnulífi og móta framtíðarsýn um betra samfélag. Samfélag sem mun skipa sér í fremstu röð í verðmætasköpun, menntun, velferð og sönnum lífsgæðum. Einnig er leitast við draga fram styrkleika og sóknarfæri hvers svæðis og gera tillögur og áætlanir á grunni þeirra. Þá verður leitast við að forgangsraða fjármunum, nýta auðlindir og virkja mannauð þjóðarinnar til að vinna gegn fólksflótta og leggja grunn að velsæld. Samkeppnishæfni stuðlar að hagsæld þjóða og svæða. Það er framleiðni eða verðmætasköpun sem byggist á vinnuframlagi einstaklinga, tækjum og/eða annars konar auðlindum. Aukin framleiðni hefur jákvæð áhrif á hagsæld svæðis eða þjóðar. Við skilgreiningu á árangri með aukinni samkeppnishæfni þjóða er gjarnan horft til frammistöðu í þremur meginflokkum, en þeir eru; hagsæld, umhverfi og lífsgæði/jöfnuður. Í þessari samantekt er yfirlit yfir helstu vísa sem notaðir eru til að mæla samkeppnishæfni þjóða með aðlögun sem hentar til að meta stöðu einstakra svæða. Staða Suðursvæðis er síðan mátuð við þá. Suðursvæði er skilgreint sem svæðið frá Ölfusi til Hornafjarðar í austri. Úr skilgreiningu sóknarsvæða: Á Suðurlandi búa um það bil 26.000 manns, þar af rúmlega 12.000 manns í Ölfusi, Árborg og Hveragerði. Árborg, með 8.000 íbúa, er í senn sterkur þjónustukjarni fyrir Suðursvæðið og tenging við Höfuðborgarsvæðið, en um Árborg fara flestir af Suður- og Austurlandi sem leið eiga til Höfuðborgarsvæðisins. -

Roadtrip Ijsland Voor Fotografen

ROADTRIP IJSLAND VOOR FOTOGRAFEN IJsland is op dit moment erg populair en dat merk je, enorme hoeveelheden toeristen die je tegenkomt bij de bekende bezienswaardigheden. (groei toerisme was in 2016 plus 70%) Bus ladingen vol met “standaard” toeristen, dus vooral in de weg staand en selfies makend, maken het voor de wat meer serieuze fotografen moeilijk om nog goede platen te schieten. Maar ook deze serieuze fotografen maken het elkaar soms moeilijk, 10-12 statieven met big stoppers naast elkaar voor dezelfde waterval is geen uitzondering. Nu heeft dat standaard massa toerisme ook een voordeel, het is voorspelbaar waar je ze tegen komt en dus is het met wat zoeken te ontlopen. Daarom deze roadtrip met vele tips voor fotografen die rustig willen fotograferen en hiervoor bereid zijn om van de gebaande weg af wijken. Veel mensen volgen de rondweg ( weg nr. 1) en nu is daar niets op tegen maar dat is ook de standaard weg voor het massa toerisme dus zul je zo nu en dan deze weg moeten verlaten. Ik zal proberen aan te geven hoe druk het bij de verschillende plaatsen is, de ervaringen hier voor uit 2016 en wel augustus – september (in juni – july zal het nog drukker zijn) (0) = geen toeristen (*) = weinig toeristen (*****) = zeer veel toeristen Natuurlijk zijn er ook de verplichte nummers, die ondanks de meestal vele toeristen, toch de moeite waard zijn om te bezoeken. (sommige zijn in de trip opgenomen) Deze roadtrip gaat uit van de ringweg (weg nr 1), met de klok mee en startend in Seydisfjordur. Dit omdat hier de ferry uit Denemarken aankomt en ik de reis naar IJsland altijd met de eigen auto maak. -

Orlofsshús Á Kortinu Má Sjá Staðsetningu Orlofshúsa Félags Iðn- Og Tæknigreina 2 Ágæti Félagsmaður

Orlofsshús Á kortinu má sjá staðsetningu orlofshúsa Félags iðn- og tæknigreina 2 Ágæti félagsmaður Sum ar út leiga (júní-ágúst) Pantanir utan sumarleyfistíma Að vori eru send út um sókn ar eyðu blöð til fé lags- Til að panta orlofshús eru fjórar leiðir færar. manna, þar sem gef inn er kost ur á allt að sex val- Einfaldast er að fara inn á www.fit.is og panta mögu leik um. Því fleiri val kosti sem merkt er við, laus orlofshús og velja hús, skrá greiðslukorta- þeim mun meiri lík ur eru á út hlut un. Út hlut un ar- upplýsingar og prenta út samning. Þá er einnig hægt regl ur er að finna hér aft ar í bæk lingn um. að senda tölvupóst á [email protected] eða hringja í síma 535 6000, þá verður að greiða með korti í gegnum Vetr ar út leiga síma eða fá bankaupplýsingar og leggja inn áður en Flest húsa okk ar eru einnig til út leigu að vetri til. samningur er sendur. Þá er ekki stuðst við punkta kerfi held ur ræð ur hver pant ar fyrst ur. Vetr ar út hlut un skerð ir ekki rétt til sum ar út hlut un ar nema um páska. Öryggisnúmerin Ef slys ber að höndum, hafið þá samband við neyðarlínuna í síma 112 og gefið upp öryggisnúmer hússins sem þið eruð stödd í. Með kærri kveðju og von um að dvölin verði ykkur ánægjuleg Stjórn Fé lags iðn- og tækni greina Efnisyfirlit • Skorradalur - Borgarfjarðarsýslu ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 4-5 • Húsafell - Borgarfjarðarsýslu .......................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Download Photo Guide to Iceland

PHOTO GUIDE TO ICELAND PHOTO GUIDE TO ICELAND Photographs and text by Finnur P. Fróðason (Finn) and Haukur Parelius Finnsson (Hawk) Foreword by Andy Cook of Rocky Mountain Reflections Photography, Inc. Text on safety by safetravel.is Proofreading and editing by Mira Astrid Sorensen Design and layout by Arngrímur Arnarson and Hróbjartur Sigurðsson at Blokkin (www.blokkin.is) Published by Ýma ehf., Garðabær, Iceland First edition published in Iceland, January 2015 Copyright © Ýma ehf., 2015 – All rights reserved The photographs, text, and this e-book in its entirety are copyrighted and protected by Icelandic and international copyright laws. However, you are welcome to share this e-book with all your friends, provided it is for non-commercial purposes and you acknowledge the source. DISCLAIMER The authors have made every effort to ensure that the information and data are accurate at the time of publication; however, please do not follow these heedlessly and use your own judgement. Please note that GPS systems can have different datums, and that the GPS points in this book have been taken using a few different devices. Opinions and advice are the subjective views of the authors, put forward responsibly, in good faith and to the best of their knowledge. The publisher and the authors disclaim any liability for damages arising from the use or misuse of the information contained in this e-book. COVER IMAGE Lava by Leirhnjúkur in North Iceland. Photo by Hawk EF70-200mm f/2.8L IS USM @ 100mm Canon 5D Mrk III f25, 3.2 September 19, 2014, 17:33 GMT ISO 200 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT THE AUTHORS .................................................