Nineteenth International Seapower Symposium: Report of the Proceedings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

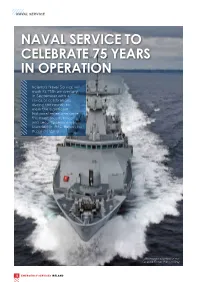

Naval Service to Celebrate 75 Years in Operation

NAVAL SERVICE NAVAL SERVICE TO CELEBRATE 75 YEARS IN OPERATION Ireland’s Naval Service will mark its 75th anniversary in September with a series of celebrations during the month to mark the significant historical milestone since the maritime, defence and security service was founded in 1946. Report by Ruairí de Barra. (All images courtesy of the Defence Forces Press Office) 12 EMERGENCY SERVICES IRELAND NAVAL SERVICE uring his recent anniversary and small boats, shall address, the current Flag then sail to Cork City, for Officer Commanding the a civic reception hosted Naval Service (FOCNS), by the Lord Mayor of DCommodore Michael Malone, said: Cork, Colm Kelleher. “Underpinning our achievements While it is hoped over the last 75 years have been our that public events such personnel and their families at home. as the ‘Meet the Fleet – “I take this opportunity to thank, It’s Your Navy’ planned not only those who have served in the tours of the ships will Naval Service, but those who have be well attended, they supported them. The mothers, fathers, are all dependant on husbands, wives, family and friends restrictions in place at who have held the fort at home and the time. Other events who have also made sacrifices, so that planned for September others could serve.” include a ‘Naval Family Celebrations planned for the Day’, the publication month of September include a of a special book of ‘Meet the Fleet’ event in Dublin photographs, a special and Cork. A number of vessels shall edition of the Defence visit Dublin, where the President Forces’ magazine ‘An “Underpinning our achievements over the last 75 Michael D. -

The 'Blue Green' Ship a Look at Intelligence Section Naval Service

ISSN 0010-9460 00-An Cos-DEC-05(p1-11)1/12/056:59pmPage1 0 9 THE DEFENCEFORCESMAGAZINE DECEMBER2005 9 770010 946001 UNOCI Mission inCôted’Ivoire Naval ServiceReserve A LookatIntelligence Section The ‘BlueGreen’Ship € 2.20 (Stg£1.40) 00-An Cos-DEC-05 (p1-11) 5/12/05 10:11 am Page 3 An Cosantóir VOLUME 65 inside Number 9 December 2005 EDITORIAL MANAGER: Capt Fergal Costello Over the next two issues, to mark the establishment of the new Reserve Defence Force and the beginning of the integration process, An Cosantóir will feature a substantial number of features looking at the EDITOR: activities of our Reserve units. In this month's magazine we have articles on the Naval Reserve, medics, Sgt Willie Braine and air defence, we also have a 'vox pop' of personnel, giving their views on life in the Reserve. For those of you wondering what has happened to your October and November issues, you will be receiv- JOURNALISTS: ing a double-size issue commemorating 50 years of Ireland's membership of the United Nations, from the Terry McLaughlin Defence Forces' point of view. This special issue, which will cover all of our UN missions since our first, Wesley Bourke UNOGIL, in 1958, up to the present missions in Liberia, Kosovo and Ivory Coast, among many others, will be coming out to coincide with the anniversary of our accession to the UN on December 14th. CONNECT: Sgt David Nagle The ‘Blue Green’ PDFORRA PHOTOGRAPHER: Armn Billy Galligan Ship – Yes or No? 7 Annual 20 A new type of ship for Delegate SUBSCRIPTIONS: the Naval Service? Sgt David Nagle Report by Conference Cmdr Mark Mellet Report by ADVERTISING: Terry McLaughlin Above Board Publishing Paul Kelly, Advertising Manager Tel: 0402-22800 Getting on Looking Printed by Kilkenny People, Board 12 Forward 23 Kilkenny. -

Vice Admiral Luke M. Mccollum Chief of Navy Reserve Commander, Navy Reserve Force

2/16/2017 U.S. Navy Biographies VICE ADMIRAL LUKE M. MCCOLLUM Vice Admiral Luke M. McCollum Chief of Navy Reserve Commander, Navy Reserve Force Vice Adm. Luke McCollum is a native of Stephenville, Texas, and is the son of a WWII veteran. He is a 1983 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy and is a designated surface warfare officer. McCollum holds a Master of Science in Computer Systems Management from the University of Maryland, University College and is also a graduate of Capstone, the Armed Forces Staff College Advanced Joint Professional Military Education curriculum and the Royal Australian Naval Staff College in Sydney. At sea, McCollum served on USS Blue Ridge (LCC 19), USS Kinkaid (DD 965) and USS Valley Forge (CG 50), with deployments to the Western Pacific, Indian Ocean, Arabian Gulf and operations off South America. Ashore, he served in the Pentagon as naval aide to the 23rd chief of naval operations (CNO). In 1993 McCollum accepted a commission in the Navy Reserve where he has since served in support of Navy and joint forces worldwide. He has commanded reserve units with U.S. Fleet Forces Command, Military Sealift Command and Naval Coastal Warfare. From 2008 to 2009, he commanded Maritime Expeditionary Squadron (MSRON) 1 and Combined Task Group 56.5 in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom. He also served as the Navy Emergency Preparedness liaison officer (NEPLO) for the state of Arkansas. As a flag officer, McCollum has served as reserve deputy commander, Naval Surface Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet; vice commander, Naval Forces, Central Command, Manama, Bahrain; Reserve deputy director, Maritime Headquarters, U.S. -

Tensions Among Indonesia's Security Forces Underlying the May 2019

ISSUE: 2019 No. 61 ISSN 2335-6677 RESEARCHERS AT ISEAS – YUSOF ISHAK INSTITUTE ANALYSE CURRENT EVENTS Singapore | 13 August 2019 Tensions Among Indonesia’s Security Forces Underlying the May 2019 Riots in Jakarta Made Supriatma* EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • On May 21-22, riots broke out in Jakarta after the official results of the 2019 election were announced. These riots revealed a power struggle among retired generals and factional strife within the Indonesian armed forces that has developed since the 1990s. • The riots also highlighted the deep rivalry between the military and the police which had worsened in the post-Soeharto years. President Widodo is seen to favour the police taking centre-stage in upholding security while pushing the military towards a more professional role. Widodo will have to curb this police-military rivalry before it becomes a crisis for his government. • Retired generals associated with the political opposition are better organized than the retired generals within the administration, and this can become a serious cause of disturbance in Widodo’s second term. * Made Supriatma is Visiting Fellow in the Indonesia Studies Programme at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. 1 ISSUE: 2019 No. 61 ISSN 2335-6677 INTRODUCTION The Indonesian election commission announced the official results of the 2019 election in the wee hours of 21 May 2019. Supporters of the losing candidate-pair, Prabowo Subianto and Sandiaga Uno, responded to the announcement with a rally a few hours later. The rally went on peacefully until the evening but did not show any sign of dispersing after the legal time limit for holding public demonstrations had passed. -

After Lacklustre Performances, Selectors Face Asian Championship Dilemma by Reemus Fernando Events - Y

Friday 2nd October, 2009 15 After lacklustre performances, selectors face Asian Championship dilemma by Reemus Fernando events - Y. P. Y. Ajith (Sri Lanka Army) - 52.87 seconds in the 400 metres men’s hur- Just five athletes came up with per- dles. formances above or close to qualifying Glucoline Challenge Trophy for the standards at the 87th National Athletics best performances in women’s hurdles Championships which ended on - U. G. D. Sandamali (Sri Lanka Air Force) Wednesday. 1:01.67 seconds in the 400 metres women’s This has placed the National selectors hurdles. in a dilemma as they have to name a team Governor General’s Cup for the of 19 for the forthcoming Asian Athletic best performance in middle and long Championships which will be held in distance running- Chaminda Wijekoon China in November. (Sri Lanka Army) 3:43.80 seconds in the Chaminda Wijekoon and Decathlon men’s 1500 metres. champion Mohamed Sameer, who estab- Huxley’s Wintergino Challenge lished new Sri Lanka records, sprinters Trophy for the best performance in Rohitha Pushpakumara and Chandrika women’s middle and long distance Subashini who did well in the 400 metres events - N. M. C. Dilrukshi (Sri Lanka and Priyangika Madumanthi in the Army) 2:09.96 seconds in the men’s 800 women’s high jump were the athletes who metres. displayed promise in the three day meet Dr. Nagalingam which ended on Wednesday. Ethirweerasingam Trophy for the best high jumper of the meet – A. D. Wijekoon was the only athlete to Challenge Trophy winners with their awards at the 87th National Athletics Championship which ended at the Sugathadasa N. -

CHRISTMAS MESSAGES Michael D

CHRISTMAS MESSAGES Michael D. Higgins Uachtarán na hÉireann Simon Coveney TD Minister for Defence Christmas Message CHRISTMAS MESSAGE TO THE DEFENCE FORCES FROM MINISTER OF DEFENCE SIMON COVENEY December 2020 To the men and women of our Defence Forces. Thank you for your service and your dedication in 2020, a year none of us will ever forget. To those serving overseas - your work has never been more valued and I know the sacrifice of being away from your family for months on end is even more acute this year given the fears at home of the virus. I know you have worried about the welfare and health of elderly and vulnerable relatives at home in the same way they usually about you when you’re abroad. I know your partners have carried extra weight this year and I know your children have worried about the virus. I want you to know that the people and government of Ireland are immensely proud of you and grateful to you. To those who have served at home this year - working from home was not really an option for our men and women in uniform, so when the roads were empty and most citizens were staying within 2km of their homes, you were at your post. The Defence Forces have been a constant and professional partner to the HSE in protecting our citizens in this pandemic. No task has been too big or too small and you have served with distinction. I was proud to return as Minister for Defence this year and my pledge to you in the years that I hold this office is to represent you at the cabinet table and to continue to highlight your work to our citizens. -

January 10, 2018 Mr. Al Bocchicchio, Director in Speaking for The

Home of Home 28073 Avenue, Grover, NC Cleveland of 301 theThe Inn Patriots™ The Museum® Presidential Culinary January 10, 2018 Mr. Al Bocchicchio, Director In speaking for the Under Secretary for Benefits Department of Veterans Affairs Atlanta Regional Office 1700 Clairmont Road Decatur, Georgia 30033 , IAHHRM MEMORANDUM: How the VA home loan code and Lenders Handbook 26-7 inadvertently, and is possibly mistakenly, blocking, inhibiting and preventing veteran success stories thus, perhaps contributing to ™ substantial rates of veteran suicides and The Presidential Service Center The Presidential Dear Al, www.theinnofthepatriots.com It has taken this disabled and injured veteran a while to answer your letter. I have been doing more research on the VA home loan code. (Perl, 2017) I understand your quoting of the VA Home Loan Lenders regulations to the Presidential Inquiry launched by then President Obama. That White House then, like this White House now, and others keep asking the same questions about the VA. What, and who is stopping veterans from becoming a success in the changing economy of 2018? ® BACKGROUNDER, WHO, WHERE, WHAT, WHEN: In 2008 my veteran disabled wife and myself (also a disabled vet, 30-year retired) opened a B&B in Grover, NC under a lease. We live in the home with our seven-year-old daughter. In 2012 we bought the house, but we were denied use of our VA loan six times, by six different banks. We have been unable ever to use our VA loan guarantee program and benefit as vets. I was once a homeless veteran living in a cargo van and closet after returning from OIF and OEF. -

Studenti II Godine O Međunarodnoj Zajednici Biografije Poznatih

Pravni fakultet Osijek Međunarodno pravo Studenti II godine o međunarodnoj zajednici Biografije poznatih aktivista, političara, državnika i povijesnih osoba Tekstove uredili: Mira Lulić i Davor Muhvić Osijek, 2020. SADRŽAJ Riječ-dvije o ovoj zbirci studentskih tekstova ................................................................................ 4 I. Aktivisti i promotori ljudskih prava ........................................................................................ 5 1. AMAL ALAMUDDIN CLOONEY (Ujedinjeno Kraljevstvo) ...................................................... 5 2. Dr. SHIRIN EBADI (Iran) ...................................................................................................... 7 3. BILL GATES (Sjedinjene Američke Države) .......................................................................... 9 4. CHEN GUANGCHENG (Kina) ............................................................................................. 12 5. HARRY, VOJVODA OD SUSSEXA (Ujedinjeno Kraljevstvo) .................................................. 14 6. ANGELINA JOLIE (Sjedinjene Američke Države) ................................................................. 16 7. AUNG SAN SUU KYI (Mianmar) ........................................................................................ 18 8. GRETA THUNBERG (Švedska) ........................................................................................... 21 9. WILLIAM, VOJVODA OD CAMBRIDGEA (Ujedinjeno Kraljevstvo) ....................................... 23 10. OPRAH WINFREY (Sjedinjene -

Ledning I Försvarsmakten Svenska Militära Chefers Erfarenheter

Ledning i Försvarsmakten Svenska militära chefers erfarenheter MAGDALENA GRANÅSEN, LINDA SJÖDIN, HELENA GRANLUND FOI är en huvudsakligen uppdragsfinansierad myndighet under Försvarsdepartementet. Kärnverksamheten är forskning, metod- och teknikutveckling till nytta för försvar och säkerhet. Organisationen har cirka 1000 anställda varav ungefär 800 är forskare. Detta gör organisationen till Sveriges största forskningsinstitut. FOI ger kunderna tillgång till ledande expertis inom ett stort antal tillämpningsområden såsom säkerhetspolitiska studier och analyser inom försvar och säkerhet, bedömning av olika typer av hot, system för ledning och hantering av kriser, skydd mot och hantering av farliga ämnen, IT-säkerhet och nya sensorers möjligheter. FOI Totalförsvarets forskningsinstitut Tel: 08-55 50 30 00 www.foi.se Försvarsanalys Fax: 08-55 50 31 00 164 90 Stockholm FOI-R--3375--SE Underlagsrapport Försvarsanalys ISSN 1650-1942 December 2011 Magdalena Granåsen, Linda Sjödin, Helena Granlund Ledning i Försvarsmakten Svenska militära chefers erfarenheter Omslagsbild: Bildkollage av Henric Roosberg FOI-R--3375--SE Ledning i Försvarsmakten. Svenska militära chefers Titel erfarenheter. Title Command and Control in the Swedish Armed Forces. Experiences of Swedish military commanders. Rapportnr/Report no FOI-R--3375--SE Rapporttyp/ Report Type Underlagsrapport/ Base data report Sidor/Pages 25 p Månad/Month December Utgivningsår/Year 2011 ISSN Kund/Customer Försvarsmakten Projektnr/Project no E11109 Godkänd av/Approved by Markus Derblom FOI, Totalförsvarets -

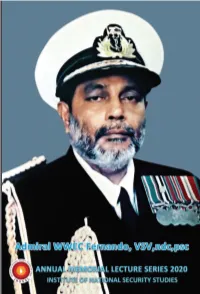

Defenc Book 2021 07 05 Print Layout 1

ANNUAL MEMORIAL LECTURE SERIES 2020 The Institute of National Security Studies (INSS) is the premiere national security think tank of Sri Lanka established under the Ministry of Defence, to understand the security environment and to work with government to craft evidence based policy options and strategies for debate and discussion to ensure national security. The institute will conduct a broad array of national security research for the Ministry of Defence. Institute of National Security Studies 8th Floor, “SUHURUPAYA”, Battaramulla, Sri Lanka Tel: +94 11 2879087 | Fax: +94 11 2879086 E mail: [email protected] www.insssl.lk ISBN: 978 624 5534 01 2 ANNUAL MEMORIAL LECTURE SERIES 2020 “Sea Power of an Island Nation and Admiral Clancy Fernando,” In honor of late Admiral Wannakuwatta Waduge Erwin Clancy Fernando VSV, ndc, psc INSTITUTE OF NATIONAL SECURITY STUDIES ANNUAL MEMORIAL LECTURE SERIES 2020 This publication includes speeches delivered during Annual Memorial Lecture Series 2020 by General Kamal Gunaratne (Retd) WWV RWP RSP USP ndc psc MPhil Secretary to the Ministry of Defence, State Ministry of National Security and Disaster Management, Admiral Prof. Jayanath Colombage RSP, VSV, USP, rcds, psc Director General of Institute of National Security Studies and Admiral Thisara Samarasingha RSP, VSV, USP,ndc, psc,DBA on 19th February 2021. The views expressed herein do not represent a consensus of views amongst the worldwide membership of the Institute as a whole. First published in July 2021 © 2020 Institute of National Security Studies (INSS) ISBN 978-624-5534-01-2 Edited by K.A. Waruni Madhubhashini You are free to use any materials in this paper for publication in newspaper, online networks, newsletters, radio/TV discussions, academic papers or for other means, so long as full credit is given to the Institute of National Security Studies (INSS). -

Laporan Tahunan Aji 2015 Cerdas Cerdas Memilih Memilih Media Media

LAPORAN TAHUNAN AJI 2015 CERDAS CERDAS MEMILIH MEMILIH MEDIA MEDIA DI BAWAH BAYANG-BAYANG KRISIS Laporan Tahunan AJI 2015 DI BAWAH BAYANG-BAYANG KRISIS Laporan Tahunan AJI 2015 PENULIS: Abdul Manan EDITOR: Suwarjono PENYUMBANG BAHAN: Asep Saefullah, Yudhie Tirzano, Hesthi Murti, Bayu Wardhana DITERBITKAN OLEH Aliansi Jurnalis Independen (AJI) Indonesia, 2015 Jl. Kembang Raya No. 6, Kwitang, Senen, Jakarta Pusat Telp. +62 21 3151214, Fax. +62 21 3151261 Website : www.aji.or.id Email: [email protected] Twitter : @AJIIndo Fb : Aliansi Jurnalis Independen KATA PENGANTAR da yang berbeda dengan buku Laporan Tahunan Aliansi Jurnalis Independen (AJI) tahun 2015 ini. A Selain lebih tipis, buku laporan tahunan kali ini lebih banyak menggambarkan situasi yang dihadapi AJI dalam mewujudkan visi dan misi di tengah dinamika masyarakat, industri media dan negara. Banyak catatan penting terkait isu jurnalistik maupun perkembangan media nasional dan global sepanjang tahun 2014-2015. Ada kabar baik dan ada kabar yang kurang meng- gembirakan. Kabar baiknya adalah media di Indonesia terus tumbuh mengikuti perkembangan teknologi yang mendorong perubahan besar-besaran dalam cara mengakses informasi. Masyarakat semakin lengket dengan gawai dalam mencari informasi. Informasi semakin mudah dan murah didapat, cukup melalui genggaman tangan. Masyarakat tidak hanya sebagai penikmat informasi, namun juga menjadi sumber informasi. Teknologi Internet telah mengubah cara memproduksi berita atau menyampaikan pesan ke publik. Kabar kurang menggembirakannya, teknologi ini menimbulkan kerentanan baru. Batas-batas kebebasan masyarakat menyampaikan pendapat dipertanyakan. Ruang publik yang muncul dari teknologi Internet (hendak) dibatasi melalui regulasi. UU Informatika dan Transaksi Elektronik yang berlaku sejak tahun 2008, sudah membuat lebih dari 100 orang masuk tahanan karena pendapat atau ekspresinya di LAPORAN TAHUNAN AJI 2015 | III Internet. -

Eighteenth International Seapower Symposium: Report of the Proceedings

U.S. Naval War College U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons International Seapower Symposium Events 10-2007 Eighteenth International Seapower Symposium: Report of the Proceedings The U.S. Naval War College Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/iss Recommended Citation Naval War College, The U.S., "Eighteenth International Seapower Symposium: Report of the Proceedings" (2007). International Seapower Symposium. 3. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/iss/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Events at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Seapower Symposium by an authorized administrator of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen EIGHTEENTH INTERNATIONAL SEAPOWER SYMPOSIUM Report of the Proceedings ISS18.prn C:\Documents and Settings\john.lanzieri.ctr\Desktop\NavalWarCollege\5164_NWC_ISS-18\Ventura\ISS18.vp Friday, August 28, 2009 3:11:10 PM Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen ISS18.prn C:\Documents and Settings\john.lanzieri.ctr\Desktop\NavalWarCollege\5164_NWC_ISS-18\Ventura\ISS18.vp Friday, August 28, 2009 3:11:12 PM Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen EIGHTEENTH INTERNATIONAL SEAPOWER SYMPOSIUM Report of the Proceedings 17–19 October 2007 Edited by John B. Hattendorf Ernest J. King Professor of Maritime History Naval War College with John W. Kennedy NAVAL WAR COLLEGE NEWPORT,RHODE ISLAND