Tanzania's Mediation Process in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entanglements of Modernity, Colonialism and Genocide Burundi and Rwanda in Historical-Sociological Perspective

UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS Entanglements of Modernity, Colonialism and Genocide Burundi and Rwanda in Historical-Sociological Perspective Jack Dominic Palmer University of Leeds School of Sociology and Social Policy January 2017 Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ii The candidate confirms that the work submitted is their own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. ©2017 The University of Leeds and Jack Dominic Palmer. The right of Jack Dominic Palmer to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by Jack Dominic Palmer in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would firstly like to thank Dr Mark Davis and Dr Tom Campbell. The quality of their guidance, insight and friendship has been a huge source of support and has helped me through tough periods in which my motivation and enthusiasm for the project were tested to their limits. I drew great inspiration from the insightful and constructive critical comments and recommendations of Dr Shirley Tate and Dr Austin Harrington when the thesis was at the upgrade stage, and I am also grateful for generous follow-up discussions with the latter. I am very appreciative of the staff members in SSP with whom I have worked closely in my teaching capacities, as well as of the staff in the office who do such a great job at holding the department together. -

Will Hutus and Tutsis Live Together Peacefully ?

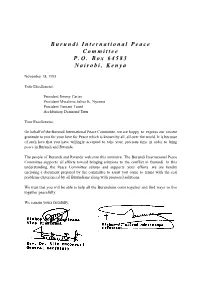

B u r u n d i I n t e r n a t i o n a l P e a c e C o m m i t t e e P . O . B o x 6 4 5 8 3 N a i r o b i , K e n y a November 18, 1995 Your Excellencies. President Jimmy Carter President Mwalimu Julius K. Nyerere President Tumani TourŽ Archbishop Desmond Tutu Your Excellencies, On behalf of the Burundi International Peace Committee, we are happy to express our sincere gratitude to you for your love for Peace which is known by all, all over the world. It is because of such love that you have willingly accepted to take your precious time in order to bring peace in Burundi and Rwanda. The people of Rurundi and Rwanda welcome this initiative. The Burundi International Peace Committee supports all efforts toward bringing solutions to the conflict in Burundi. In this understanding, the Peace Committee salutes and supports your efforts. we are hereby enclosing a document prepared by the committee to assist you come to terms with the real problems experienced by all Burundians along with proposed solutions. We trust that you will be able to help all the Burundians come together and find ways to live together peacefully. We remain yours faithfully, WILL HUTUS AND TUTSIS LIVE TOGETHER PEACEFULLY ? Introduction More than two years have passed since the assassination of President Melchior Ndadaye of Burundi. Since then, many people have lost their lives and continue to die. One wonders whether it will be possible again for Hutus and Tutsis to live together peacefully. -

List of Prime Ministers of Burundi

SNo Phase Name Took office Left office Duration Political party 1 Kingdom of Burundi (part of Ruanda-Urundi) Joseph Cimpaye 26-01 1961 28-09 1961 245 days Union of People's Parties 2 Kingdom of Burundi (part of Ruanda-Urundi) Prince Louis Rwagasore 28-09 1961 13-10 1961 15 days Union for National Progress 3 Kingdom of Burundi (part of Ruanda-Urundi) André Muhirwa 20-10 1961 01-07 1962 254 days Union for National Progress 4 Kingdom of Burundi (independent country) André Muhirwa 01-07 1962 10-06 1963 344 days Union for National Progress 5 Kingdom of Burundi (independent country) Pierre Ngendandumwe 18-06 1963 06-04 1964 293 days Union for National Progress 6 Kingdom of Burundi (independent country) Albin Nyamoya 06-04 1964 07-01 1965 276 days Union for National Progress 7 Kingdom of Burundi (independent country) Pierre Ngendandumwe 07-01 1965 15-01 1965 10 days Union for National Progress 8 Kingdom of Burundi (independent country) Pié Masumbuko 15-01 1965 26-01 1965 11 days Union for National Progress 9 Kingdom of Burundi (independent country) Joseph Bamina 26-01 1965 30-09 1965 247 days Union for National Progress 10 Kingdom of Burundi (independent country) Prince Léopold Biha 13-10 1965 08-07 1966 268 days Union for National Progress 11 Kingdom of Burundi (independent country) Michel Micombero 11-07 1966 28-11 1966 140 days Union for National Progress 12 Republic of Burundi Albin Nyamoya 15-07 1972 05-06 1973 326 days Union for National Progress 13 Republic of Burundi Édouard Nzambimana 12-11 1976 13-10 1978 1 year, 335 days Union for -

Assassinat Du Premier Ministre Du Burundi, Pierre Ngendandumwe Cinquante Ans Après Par Perpétue Nshimirimana, Le 15 Janvier 2015

Assassinat du Premier ministre du Burundi, Pierre Ngendandumwe Cinquante ans après Par Perpétue Nshimirimana, le 15 janvier 2015 Contribution à la Commission Vérité-Réconciliation et au Mécanisme de Justice Transitionnelle L’année 2015 est une année particulière dans l’Histoire du Burundi. Elle marque, en effet, le cinquantième anniversaire du déclenchement des premiers assassinats en masse des citoyens et des intellectuels burundais ayant en commun le fait d’appartenir à l’ethnie Hutu. Cet anniversaire invite tous les Barundi épris de justice et de paix à marquer un temps d’arrêt pour une pensée envers toutes les victimes innocentes du pays. Aujourd’hui, le public attend, précisément, de la part des dirigeants du Burundi officiel, de vrais gestes symboliques et concrets dans le but d’honorer leur mémoire et de lutter contre l’oubli suivi d’une impunité invraisemblable. L’année 2015 donne l’occasion, aussi, de se souvenir en particulier de ces illustres disparus, les vrais Bâtisseurs du Burundi moderne. Il faut les mettre en lumière pour assurer la pérennité de leurs idées et de leurs projets. Au moment où le pays se dote, enfin, des membres constitutifs de la Commission Vérité et Réconciliation (C.V.R.)1, le Burundi doit regarder en face son passé et délivrer l’entière vérité à sa population en souffrance depuis si longtemps. De nombreuses familles sont dans l’attente d’explications sur l’étendue du mal répandu en toute conscience et avec détermination. Le temps de la réhabilitation des personnes injustement accusées puis assassinées dans la foulée, au cours de l’année 1965, est arrivé. -

Resource Scarcity and Social Identity in the Political Conflicts in Burundi

Resource Scarcity and Social Identity in the Political Conflicts in Burundi by Elisabeth Naito Jengo Dissertation presented for the degree of Master of Political Science (International Studies) in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Promotor: Prof Pierre du Toit March 2013 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. November 2012 Copyright © 2013 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT Since Burundi gained independence in 1962, this country has experienced periods of mass communal violence. Extensive scholarly research has focused on exploring the factors behind, and the nature of, the conflicts in Burundi from a socio-ethnic perspective. There has, however, been a persistent lack of attention paid to the inextricable relationship between environmental factors; particularly the scarcity of resources, coupled with rapid population growth; and Burundi‘s recent history of internal conflict. Noteworthy explanatory factors, which are often ignored in literature on the environment and conflict, have thus motivated this study. Burundi is an example of this reality because of a highly dependent agricultural economy and a constant growing population. This study used a descriptive analysis, as methodological tool; in order to gain an understanding of Burundi‘s land question - that is, how limited access to land and the constantly increasing population have led to environmental degradation, that served as motivational trigger factors for the violent political conflicts that occurred at various periods between 1965 and 1993 in this country. -

Distributional Conflict, the State, and Peace Building in Burundi

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Economics Department Working Paper Series Economics 2005 Distributional conflict, the state, and peace building in Burundi Léonce Ndikumana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/econ_workingpaper Part of the Economics Commons Recommended Citation Ndikumana, Léonce, "Distributional conflict, the state, and peace building in Burundi" (2005). Economics Department Working Paper Series. 49. https://doi.org/10.7275/1069125 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Economics at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Economics Department Working Paper Series by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS Working Paper Distributional conflict, the state, and peace building in Burundi by Léonce Ndikumana Working Paper 2005-13 UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST Distributional conflict, the state, and peace building in Burundi Léonce Ndikumana* Department of Economics University of Massachusetts Amherst, MA 01003 Tel: (413) 545-6359; Fax: (413) 545-2921 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www-unix.oit.umass.edu/~ndiku This draft: June 2005 Abstract This paper examines the causes of conflict in Burundi and discusses strategies for building peace. The analysis of the complex relationships between distribution and group dynamics reveals that these relationships are reciprocal, implying that distribution and group dynamics are endogenous. The nature of endogenously generated group dynamics determines the type of preferences (altruistic or exclusionist), which in turn determines the type of allocative institutions and policies that prevail in the political and economic system. While unequal distribution of resources may be socially inefficient, it nonetheless can be rational from the perspective of the ruling elite, especially because inequality perpetuates dominance. -

Africa Generation News) « Burundi : Un an Par Le Trou De La Serrure (De Janvier 2013 À Septembre 2013)»

Découvrez quelques extraits tirés des annexes du bilan annuel d’AGnews (Africa Generation News) « Burundi : Un an par le trou de la serrure (de janvier 2013 à Septembre 2013)» : L'Acteur de la société burundaise : La Société Civile ( Sources : AGnews, arib.info, Xinhua, Afriquinfos, radio -rtr/rpa/rtnb/isanganiro/bonesha/Rema/ccib/radio culture - ,burundi-info.com, nyabusorongo.org ) ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ SEPTEMBRE 2013 27 septembre 2013 | Burundi : La société civile se mobilise pour les préparatifs de l' AIAF-2014 / BUJUMBURA (Xinhua) - La société civile burundaise est mobilisée pour les préparatifs de l'Année Internationale de l'Agriculture Familiale prévue en 2014(AIAF-2014) pour interpeller le gouvernement burundais sur l'impérieuse nécessité de soutenir la promotion de l'agriculture familiale en célébrant solennellement l'AIAF-2014. M. Richard Sahinguvu, directeur de l'antenne nationale de l'Institut Africain pour le Développement Economique et Social ( INADES-Formation Burundi) et Coordonnateur du comité national des Organisations de la Société Civile(OSC) en charge de ces préparatifs, a affirmé jeudi à Xinhua que les enjeux de la célébration de l'AIAF-2014 pour le Burundi sont énormes. "En célébrant l'AIAF-2014, le gouvernement burundais se sera engagé à élaborer des politiques susceptibles de promouvoir le développement de l'agriculture familiale au Burundi. Avec l'élaboration des politiques visant la promotion de l'agriculture familiale, le paysan burundais pourrait bénéficier d'un cadre approprié pour s'auto développer tout en contribuant à la sécurité alimentaire de tout le pays en général", a précisé M. Sahinguvu. A la question de savoir si ces propos sous-tendent que l' agriculture familiale n'est pas développée au Burundi, M. -

Scandale D'une Enquête Au Burundi. Analyse Critique Du Rapport S/1996

Scandale d'une enqu•te de l'ONU au Burundi Une analyse critique du Rapport S/1996/682 de L'ONU sur le putsch sanglant du 21 octobre 1993 Analyse rŽalisŽe par le G.R.A.B. (Groupe de RŽflexion et d'Action pour le Burundi) Bruxelles, FŽvrier 1997 i Les auteurs de la prŽsente analyse sontÊ: Anatole BACANAMWO, Zacharie BACANAMWO, Mam•s BANSUBIYEKO, Jean-Baptiste BIGIRIMANA, FŽlix KUBWAYO, Joseph NTAKIRUTIMANA, Rapha‘l NTIBAZONKIZA, Cyriaque SABINDEMYI, Xavier WAEGENAERE, Ferdinand NGENDABANKA ii Liste des abrŽviations ARIB Association pour la RŽflexion et l'Information sur le Burundi CEI Commission d'Enqu•te Internationale FRODEBU Front pour la DŽmocratie au Burundi GRAB Groupe de RŽflexion et d'Action pour le Burundi ONG Organisation Non Gouvernementales ONU Organisation des Nations Unies OUA Organisation de l'UnitŽ Africaine PL Parti LibŽral PP Parti du Peuple PRP Parti pour la RŽconciliation du Peuple, originellement appelŽ Parti Royaliste Parlementaire RADDES Rassemblement pour la DŽmocratie, le DŽveloppement Economique et Social RPB Rassemblement du Peuple Burundais SRD SociŽtŽ RŽgionale de DŽveloppement UPRONA Union pour le Progr•s National CNDD Conseil National pour la DŽfense de la DŽmocratie iii TABLE DES MATIéRES AVANT-PROPOS ................................................................................... 1 PRESENTATION GENERALE................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................... 4 CHAPITRE IÊ: UNE PROCEDURE D'ENQUETE -

Comparative Reconciliation Politics in Rwanda and Burundi

Comparative Reconciliation Politics in Rwanda and Burundi Philippe Rieder A Thesis In the Humanities Doctoral Program Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Humanities) at Concordia University Montreal, Québec, Canada April 2015 © Philippe Rieder, 2015 Signature Page Main Supervisor Frank Chalk Committee member Peter Stoett Committee member Andrew Ivaska Chair Steven High External Examiner René Lemarchand Examiner for Humanities Doctoral Program Maurice Charland iii Abstract Comparative Reconciliation Politics in Rwanda and Burundi Philippe Rieder, Ph.D. Concordia University, 2015 This thesis functions as a comparative exercise juxtaposing reconciliation politics in Rwanda and Burundi from a bottom-up perspective. Rwanda and Burundi have been labeled 'twins' before. Both countries have a very similar population structure and history of mass violence. However, their post- conflict processes differ. This fact renders them ideal candidates for comparison. Rwanda's 'maxi- mum approach' is compared to Burundi's 'non-approach' to reconciliation politics on two levels: official and informal. The 'official' level examines intention and politico-economic context from the government's side, the 'informal' level looks at how these policies have been perceived at the grass- roots and if they succeeded in reconciling the population with regard to the key objectives memory, acknowledgement, apology, recognition, and justice. The thesis analyzes and compares the advantages and disadvantages of both -

The Enigmatic Nature of the Israeli Legal System

Authors: LA Ndimurwimo and MLM Mbao L du Plessis RETHINKING VIOLENCE, RECONCILIATION AND RECONSTRUCTION IN BURUNDI eISSN 1727-3781 2015 VOLUME 18 No 4 http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/pelj.v18i4.04 LA NDIMURWIMO & MLM MBAO PER / PELJ 2015(18)4 RETHINKING VIOLENCE, RECONCILIATION AND RECONSTRUCTION IN BURUNDI LA Ndimurwimo MLM Mbao 1 Introduction Human insecurity due to armed violence particularly in the African continent is among the main obstacles preventing the attainment of sustainable economic development. Armed violence in the form of an intentional and unlawful use of force against unarmed individuals includes a wide range of crimes such as murder, assault, rape, genocide, politically-motivated killings, war crimes and crimes against humanity, as confirmed in the case of Democratic Republic of the Congo v Burundi, Rwanda and Uganda (Armed Activities case).1 The UN Security Council is entrusted with the primary responsibility of maintaining international peace and human security in line with the objectives stipulated under the UN Charter.2 However, very little has been done to maintain peace and human security in Burundi. It is common cause that Burundi has experienced gross violations of human rights since independence in 1962. Even the post-transition arrangements which were designed to consolidate the rule of law and good governance have failed to deal with these violations in a comprehensive manner. Today, ten years after the adoption of the Post-Transitional Constitution of 2005 (hereinafter Post-conflict Constitution) sexual violence against women, arbitrary detentions and extra-judicial killings, torture This article is an updated version of a paper presented to the 57th Annual Meeting of the African Studies Association, November 20-23, 2014, JW Marriott Indianapolis Hotel, Indianapolis, USA. -

La Nature Du Conflit Burundais : Cocktail Politique D'intolérance Et D'hypocrisie

Page 1of42 Site web officiel du Burundi La nature du conflit burundais : cocktail politique d'intolérance et d'hypocrisie Commission Permanente d'Etudes Politiques : (COPEP / CNDD-FDD REPUBLIQUE DU BURUNDI ( Inama y'Igihugu ) Conseil National pour la Défense de la Démocratie ( Igwanira Demokarasi) Forces pour la Défense de la Démocratie ( Ingabo zigwanira Demokarasi ) DOCUMENT N° 1 La nature du conflit burundais : cocktail politique d'intolérance et d'hypocrisie Commission Permanente d'Etudes Politiques (COPEP / CNDD-FDD) Juin 2000 "Considérant qu'il est essentiel que les droits de l'homme soient protégés par un régime de droit pour que l'homme ne soit pas contraint, en suprême recours, à la révolte contre la tyrannie et l'oppression, ( ... )"(Déclaration Universelle des Droits de l'Homme, Préambule, paragraphe 3) Table des matières 1. Introduction 2. La manifestation objective du conflit et son interprétation divergente par les protagonistes 2.1. La genèse du conflit à l'aube de l'indépendance et les éléments objectifs de son développement postcolonial 2.2. La perception et la présentation du conflit par l'élite tutsi 2.2.1. L'occultation systématique du conflit (1962-1988) 2.2.2. La reconnaissance brutale du conflit (depuis 1988) 2.3. La perception et la présentation du conflit par l'élite hutu 3. Les thèses de légitimation respective dans le développement structurel de la violence politique 4. Les prolongements inavoués des thèses de légitimation de la violence politique et les enjeux réellement en présence 4.1. Mise en perspective générale du conflit 4.2. L'échiquier politique de 1966 et son évolution 4.3. -

Elizabeth a Mcclintock Doctoral Dissertation 2016

SECURING THE SPACE FOR POLITICAL TRANSITION: THE EVOLUTION OF CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS IN BURUNDI A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy Tufts University by ELIZABETH ANN MCCLINTOCK In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy DECEMBER 2015 Dissertation Committee EILEEN F. BABBITT, Co-Chair PETER UVIN, Co-Chair ANTONIA HANDLER CHAYES, Reader Securing the Space for Political Transition: The Evolution of Civil-Military Relations in Burundi Curriculum Vitae ELIZABETH ANN MCCLINTOCK Founder and Managing Partner, CMPartners EXPERIENCE SUMMARY Elizabeth McClintock is a Founder and Managing Partner with CMPartners, LLC. Ms. McClintock has over 20 years of experience developing curriculum, designing training, and implementing programs in negotiation, mediation, and communication skills, conflict management, and leadership development worldwide. Ms. McClintock’s work is focused in conflict and post-conflict environments, with both public and private sector organizations. In particular, Ms. McClintock has worked in Burundi for the past 17 years, supervised projects in Timor-Leste and Liberia, and managed a multi-year, multi- country capacity building program for the World Health Organization. Specific expertise includes: ! Leadership capacity building; ! Negotiation, mediation, communication, and conflict management training; ! Multi-stakeholder meeting design and facilitation ! Training-of-trainers programming and implementation; ! Conflict assessment and training-related