VII. Historical Remarks on the Introduction of the Game of Chess Into Europe, and on the Ancient Chess-Meyi Discovered in the Isle of Lewis ; by FREDERIC MADDEN, Esq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 12Th Top Chess Engine Championship

TCEC12: the 12th Top Chess Engine Championship Article Accepted Version Haworth, G. and Hernandez, N. (2019) TCEC12: the 12th Top Chess Engine Championship. ICGA Journal, 41 (1). pp. 24-30. ISSN 1389-6911 doi: https://doi.org/10.3233/ICG-190090 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/76985/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/ICG-190090 Publisher: The International Computer Games Association All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online TCEC12: the 12th Top Chess Engine Championship Guy Haworth and Nelson Hernandez1 Reading, UK and Maryland, USA After the successes of TCEC Season 11 (Haworth and Hernandez, 2018a; TCEC, 2018), the Top Chess Engine Championship moved straight on to Season 12, starting April 18th 2018 with the same divisional structure if somewhat evolved. Five divisions, each of eight engines, played two or more ‘DRR’ double round robin phases each, with promotions and relegations following. Classic tempi gradually lengthened and the Premier division’s top two engines played a 100-game match to determine the Grand Champion. The strategy for the selection of mandated openings was finessed from division to division. -

White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents

Chess E-Magazine Interactive E-Magazine Volume 3 • Issue 1 January/February 2012 Chess Gambits Chess Gambits The Immortal Game Canada and Chess Anderssen- Vs. -Kieseritzky Bill Wall’s Top 10 Chess software programs C Seraphim Press White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents Editorial~ “My Move” 4 contents Feature~ Chess and Canada 5 Article~ Bill Wall’s Top 10 Software Programs 9 INTERACTIVE CONTENT ________________ Feature~ The Incomparable Kasparov 10 • Click on title in Table of Contents Article~ Chess Variants 17 to move directly to Unorthodox Chess Variations page. • Click on “White Feature~ Proof Games 21 Knight Review” on the top of each page to return to ARTICLE~ The Immortal Game 22 Table of Contents. Anderssen Vrs. Kieseritzky • Click on red type to continue to next page ARTICLE~ News Around the World 24 • Click on ads to go to their websites BOOK REVIEW~ Kasparov on Kasparov Pt. 1 25 • Click on email to Pt.One, 1973-1985 open up email program Feature~ Chess Gambits 26 • Click up URLs to go to websites. ANNOTATED GAME~ Bareev Vs. Kasparov 30 COMMENTARY~ “Ask Bill” 31 White Knight Review January/February 2012 White Knight Review January/February 2012 Feature My Move Editorial - Jerry Wall [email protected] Well it has been over a year now since we started this publication. It is not easy putting together a 32 page magazine on chess White Knight every couple of months but it certainly has been rewarding (maybe not so Review much financially but then that really never was Chess E-Magazine the goal). -

Herjans Dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Femininities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age

Herjans dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Femininities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age Luke John Murphy Lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni trú Félagsvísindasvið Herjans dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Femininities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age Luke John Murphy Lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni trú Leiðbeinandi: Terry Gunnell Félags- og mannvísindadeild Félagsvísindasvið Háskóla Íslands 2013 Ritgerð þessi er lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni Trú og er óheimilt að afrita ritgerðina á nokkurn hátt nema með leyfi rétthafa. © Luke John Murphy, 2013 Reykjavík, Ísland 2013 Luke John Murphy MA in Old Nordic Religions: Thesis Kennitala: 090187-2019 Spring 2013 ABSTRACT Herjans dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Feminities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age This thesis is a study of the valkyrjur (‘valkyries’) during the late Iron Age, specifically of the various uses to which the myths of these beings were put by the hall-based warrior elite of the society which created and propagated these religious phenomena. It seeks to establish the relationship of the various valkyrja reflexes of the culture under study with other supernatural females (particularly the dísir) through the close and careful examination of primary source material, thereby proposing a new model of base supernatural femininity for the late Iron Age. The study then goes on to examine how the valkyrjur themselves deviate from this ground state, interrogating various aspects and features associated with them in skaldic, Eddic, prose and iconographic source material as seen through the lens of the hall-based warrior elite, before presenting a new understanding of valkyrja phenomena in this social context: that valkyrjur were used as instruments to propagate the pre-existing social structures of the culture that created and maintained them throughout the late Iron Age. -

Chaotic Descriptor Table

Castle Oldskull Supplement CDT1: Chaotic Descriptor Table These ideas would require a few hours’ the players back to the temple of the more development to become truly useful, serpent people, I decide that she has some but I like the direction that things are going backstory. She’s an old jester-bard so I’d probably run with it. Maybe I’d even treasure hunter who got to the island by redesign dungeon level 4 to feature some magical means. This is simply because old gnome vaults and some deep gnome she’s so far from land and trade routes that lore too. I might even tie the whole it’s hard to justify any other reason for her situation to the gnome caves of C. S. Lewis, to be marooned here. She was captured by or the Nome King from L. Frank Baum’s the serpent people, who treated her as Ozma of Oz. Who knows? chattel, but she barely escaped. She’s delirious, trying to keep herself fed while she struggles to remember the command Example #13: word for her magical carpet. Malamhin of the Smooth Brow has some NPC in the Wilderness magical treasures, including a carpet of flying, a sword, some protection from serpents thingies (scrolls, amulets?) and a The PCs land on a deadly magical island of few other cool things. Talking to the PCs the serpent people, which they were meant and seeing their map will slowly bring her to explore years ago and the GM promptly back to her senses … and she wants forgot about it. -

Heraldic Terms

HERALDIC TERMS The following terms, and their definitions, are used in heraldry. Some terms and practices were used in period real-world heraldry only. Some terms and practices are used in modern real-world heraldry only. Other terms and practices are used in SCA heraldry only. Most are used in both real-world and SCA heraldry. All are presented here as an aid to heraldic research and education. A LA CUISSE, A LA QUISE - at the thigh ABAISED, ABAISSÉ, ABASED - a charge or element depicted lower than its normal position ABATEMENTS - marks of disgrace placed on the shield of an offender of the law. There are extreme few records of such being employed, and then only noted in rolls. (As who would display their device if it had an abatement on it?) ABISME - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ABOUTÉ - end to end ABOVE - an ambiguous term which should be avoided in blazon. Generally, two charges one of which is above the other on the field can be blazoned better as "in pale an X and a Y" or "an A and in chief a B". See atop, ensigned. ABYSS - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ACCOLLÉ - (1) two shields side-by-side, sometimes united by their bottom tips overlapping or being connected to each other by their sides; (2) an animal with a crown, collar or other item around its neck; (3) keys, weapons or other implements placed saltirewise behind the shield in a heraldic display. -

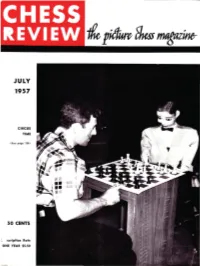

CHESS REVIEW but We Can Give a Bit More in a Few 250 West 57Th St Reet , New York 19, N

JULY 1957 CIRCUS TIME (See page 196 ) 50 CENTS ~ scription Rate ONE YEAR $5.50 From the "Amenities and Background of Chess-Play" by Ewart Napier ECHOES FROM THE PAST From Leipsic Con9ress, 1894 An Exhibition Game Almos t formidable opponent was P aul Lipk e in his pr ime, original a nd pi ercing This instruc tive game displays these a nd effective , Quite typica l of 'h is temper classical rivals in holiUay mood, ex is the ",lid Knigh t foray a t 8. Of COU I'se, ploring a dangerous Queen sacrifice. the meek thil'd move of Black des e r\" e~ Played at Augsburg, Germany, i n 1900, m uss ing up ; Pillsbury adopted t he at thirty moves an hOlll" . Tch igorin move, 3 . N- B3. F A L K BEE R COU NT E R GAM BIT Q U EE N' S PAW N GA ME" 0 1'. E. Lasker H. N . Pi llsbury p . Li pke E. Sch iffers ,Vhite Black W hite Black 1 P_K4 P-K4 9 8-'12 B_ KB4 P_Q4 6 P_ KB4 2 P_KB4 P-Q4 10 0-0- 0 B,N 1 P-Q4 8-K2 Mate announred in eight. 2 P- K3 KN_ B3 7 N_ R3 3 P xQP P-K5 11 Q- N4 P_ K B4 0 - 0 8 N_N 5 K N_B3 12 Q-N3 N-Q2 3 B-Q3 P- K 3? P-K R3 4 Q N- B3 p,p 5 Q_ K2 B-Q3 13 8-83 N-B3 4 N-Q2 P-B4 9 P-K R4 6 P_Q3 0-0 14 N-R3 N_ N5 From Leipsic Con9ress. -

Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25

Title: Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25 Introduction The UCS contains symbols for the game of chess in the Miscellaneous Symbols block. These are used in figurine notation, a common variation on algebraic notation in which pieces are represented in running text using the same symbols as are found in diagrams. While the symbols already encoded in Unicode are sufficient for use in the orthodox game, they are insufficient for many chess problems and variant games, which make use of extended sets. 1. Fairy chess problems The presentation of chess positions as puzzles to be solved predates the existence of the modern game, dating back to the mansūbāt composed for shatranj, the Muslim predecessor of chess. In modern chess problems, a position is provided along with a stipulation such as “white to move and mate in two”, and the solver is tasked with finding a move (called a “key”) that satisfies the stipulation regardless of a hypothetical opposing player’s moves in response. These solutions are given in the same notation as lines of play in over-the-board games: typically algebraic notation, using abbreviations for the names of pieces, or figurine algebraic notation. Problem composers have not limited themselves to the materials of the conventional game, but have experimented with different board sizes and geometries, altered rules, goals other than checkmate, and different pieces. Problems that diverge from the standard game comprise a genre called “fairy chess”. Thomas Rayner Dawson, known as the “father of fairy chess”, pop- ularized the genre in the early 20th century. -

The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia Religions : Ancient and Modern

RELIGION OF ANCIENT SCANDINAVIA LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO RELIGIONS ANCIENT AND MODERN THE RELIGION OF ANCIENT SCANDINAVIA RELIGIONS : ANCIENT AND MODERN. ANIMISM. By EDWARD CLODD, Author of The Story of Creation. PANTHEISM. By JAMES ALLAN SON PICTON, Author of The Religion of the universe. THE RELIGIONS OF ANCIENT CHINA. By Professor GILES, LL.D., Professor of Chinese in the University of Cambridge. THE RELIGION OF ANCIENT GREECE. By JANE HARRISON, Lecturer at Newnham College, Cambridge, Author of Prolegomena to Study of Greek Religion. ISLAM. By AMEER An SYED, M.A., C.I.E., late of H.M.'s High Court of Judicature in Bengal, Author of The Spirit of Iflam and The Ethics of Islam. MAGIC AND FETISHISM. By Dr. A. C. H ADDON, F.R.S., Lecturer on Ethnology at Cam- bridge University. THE RELIGION OF ANCIENT EGYPT. By Professor W. M. FLINDERS PETRIE, F.R.S. THE RELIGION OF BABYLONIA AND ASSYRIA. By THEOPHILUS G. PINCHES, late of the British Museum. EARLY BUDDHISM. By Professor RHYS DAVIDS, LL.D., late Secretary of The Royal Asiatic Society. HINDUISM. By Dr. L. D. BAR NEXT, of the Department of Oriental Printed Books and MSS. , British Museum. SCANDINAVIAN RELIGION. By WILLIAM A. CRAIGIE, Joint Editor of the Oxford English Dictionary. CELTIC RELIGION. By Professor ANWYL, Professor of Welsh at University College, Aberystwyth. THE MYTHOLOGY OF ANCIENT BRITAIN AND IRELAND. By CHARLES SQUIRE, Author of The Mythology of the British Islands. JUDAISM By ISRAEL ABRAHAMS, Lecturer in Talmudic Literature in Cambridge University, Author of Jewish Life in the Middle Ages. -

CHESS MASTERPIECES: (Later, in Europe, Replaced by a HIGHLIGHTS from the DR

CHESS MASTERPIECES: (later, in Europe, replaced by a HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE DR. queen). These were typically flanKed GEORGE AND VIVIAN DEAN by elephants (later to become COLLECTION bishops), though in this case, they are EXHIBITION CHECKLIST camels with drummers; cavalrymen (later to become Knights); and World Chess Hall of Fame chariots or elephants, (later to Saint Louis, Missouri 2.1. Abstract Bead anD Dart Style Set become rooKs or “castles”). A September 9, 2011-February 12, with BoarD, India, 1700s. Natural and frontline of eight foot soldiers 2012 green-stained ivory, blacK lacquer- (pawns) completed each side. work folding board with silver and mother-of-pearl. This classical Indian style is influenced by the Islamic trend toward total abstraction of the design. The pieces are all lathe- turned. The blacK lacquer finish, made in India from the husKs of the 1.1. Neresheimer French vs. lac insect, was first developed by the Germans Set anD Castle BoarD, Chinese. The intricate inlaid silver Hanau, Germany, 1905-10. Silver and grid pattern traces alternating gilded silver, ivory, diamonds, squares filled with lacy inscribed fern sapphires, pearls, amethysts, rubies, leaf designs and inlaid mother-of- and marble. pearl disKs. These decorations 2.3. Mogul Style Set with combine a grid of squares, common Presentation Case, India, 1800s. Before WWI, Neresheimer, of Hanau, to Western forms of chess, with Beryl with inset diamonds, rubies, Germany, was a leading producer of another grid of inlaid center points, and gold, wooden presentation case ornate silverware and decorative found in Japanese and Chinese clad in maroon velvet and silk-lined. -

Alphyn Capital Management, LLC

v Letter to investors, Q3 2020 Performance The Master Account, in which I am personally invested alongside SMA clients, returned -0.7% net in Q3 2020, as reported by our fund administrator. As of September 30th, 2020, the top ten positions comprised approximately 69% of the portfolio, and the portfolio held approximately 17% in cash. ACML S&P500 TR 2019 18.9% 31.5% 2020 YTD -11.0% 5.6% Growth Companies The remarkable performance of the S&P500, especially against the backdrop of COVID-19, government mandated shutdowns throughout much of the world, and stress in the “real economy” has been driven predominantly by the large technology stocks. For example, the chart below from Yardeni Research1 shows the outsized impact of the FAANMG companies on the index’s performance over the last half decade. The FAANMGs are clearly dominant companies, built by visionary founders who have developed some of the most powerful competitive advantages anywhere in the world, driven by some of the best business models. These behemoths gush cash flow (except Netflix) and enjoy rapid growth without needing to deploy much capital. We did avail ourselves of the opportunity in March of this year to pick up some AMZN and GOOG stock. Beyond the FAANMGs, the broad tech space has enjoyed impressive gains this year, especially Software as a Service (or SaaS) companies and those involved with cloud computing. For example, the WisdomTree Cloud Computing (WCLD) ETF has gained approximately 68% in 2020. These companies, overall, while not yet possessing moats as powerful as those of the FAANMGs, nevertheless are beneficiaries of the large structural shift online. -

Editors' Introduction Douglas A

Editors' Introduction Douglas A. Anderson Michael D. C. Drout Verlyn Flieger Tolkien Studies, Volume 7, 2010 Published by West Virginia University Press Editors’ Introduction This is the seventh issue of Tolkien Studies, the first refereed journal solely devoted to the scholarly study of the works of J.R.R. Tolkien. As editors, our goal is to publish excellent scholarship on Tolkien as well as to gather useful research information, reviews, notes, documents, and bibliographical material. In this issue we are especially pleased to publish Tolkien’s early fiction “The Story of Kullervo” and the two existing drafts of his talk on the Kalevala, transcribed and edited with notes and commentary by Verlyn Flieger. With this exception, all articles have been subject to anonymous, ex- ternal review as well as receiving a positive judgment by the Editors. In the cases of articles by individuals associated with the journal in any way, each article had to receive at least two positive evaluations from two different outside reviewers. Reviewer comments were anonymously conveyed to the authors of the articles. The Editors agreed to be bound by the recommendations of the outside referees. The Editors also wish to call attention to the Cumulative Index to vol- umes one through five of Tolkien Studies, compiled by Jason Rea, Michael D.C. Drout, Tara L. McGoldrick, and Lauren Provost, with Maryellen Groot and Julia Rende. The Cumulative Index is currently available only through the online subscription database Project Muse. Douglas A. Anderson Michael D. C. Drout Verlyn Flieger v Abbreviations B&C Beowulf and the Critics. -

Chess in Europe in the 5Th Century? / Thomas Thomsen

Chess in Europe in the 5th century? / Thomas Thomsen he Albanians Played Chess while Rome fell” is the headline of a press release by the Institute of World Archaeology, referring to an ivory object of 4 cm Tin height excavated at Butrint, Albania. Summarizing from the bulletin: “Butrint has been occupied since at least the 8th century BC and by the 4th century BC was an established walled settlement. It seems to have remained a small Roman port until the 6th century AD. After that, information appears to be scant. The release sug- gests – brushing aside any doubt – that the object is a chessman and that it dates to the 1st half of the 5th century. Professor Richard Hodges of the University of East Anglia is quoted as follows: “We are wondering if it is the king or queen because it has a little cross”. The description of the discovery reads: “During excava- tion of the late Roman phases of a palatial town house large urban palace, a small ivory gaming piece was found on the floor of one of the buildings, whose destruction and roof- collapse can be tightly dated to the third quarter of the 5th century. It may have fallen from the principal chamber of the house, located at first-storey level, a richly appointed reception room revetted in green-streaked cipollino marble. It must have been deposited shortly before the complex was demolished to provide material for the construction of the new expanded city wall, which almost abuts the mansion on its southern side. The piece stands only 4 cm high, and is of ivory, turned on a lathe.