World Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finalpublished.Pdf

The Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei (FEEM) Series on ____________________________________ «Climate Change and Sustainable Development» Foreword Economic development is an essential component of the life of human societies: it is crucial to provide better living conditions to present to future generations. Poverty eradication, better nutrition, access to energy, health and education are objectives almost unanimously shared by all societies, but require economic development to be achieved. Resources in our planet are however finite, and living conditions do not depend only on economic development but also on the quality of the environment. Among the threats to economic development and quality of life in this planet, climate change is certainly the most important one. But other threats, from biodiversity losses to lack of water availability, often closely interrelated with climate change, cannot be neglected when assessing the future prospect of human life on earth. This series’ goal is to provide a comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach to sustainable development and to analyze its economic, social and environmental components. FEEM’s « Climate Change and Sustainable Development » Series aims indeed at disseminating research carried out and knowledge developed within FEEM’s Climate Change and Sustainable Development program. Volumes will move from methodological tools (game theory, integrated assessment models, risk assessment tools, etc.) to economic and policy analysis of measures designed to control climate change, to offset its impacts and, more widely, to support and operationalize sustainable development. Premessa Lo sviluppo economico è una componente essenziale della vita delle nostre società: è infatti decisivo per fornire migliori condizioni di vita alle generazioni presenti e future. Ridurre la povertà, migliorare i livelli di nutrizione, fornire a tutti accesso all’energia, all’istruzione e ai servizi sanitari sono obiettivi unanimemente condivisi, ma che richiedono per essere raggiunti uno sviluppo economico diffuso e inclusivo. -

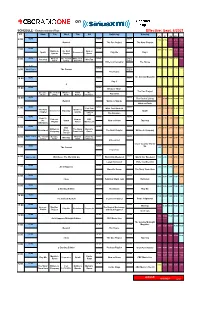

Siriusxm-Schedule.Pdf

on SCHEDULE - Eastern Standard Time - Effective: Sept. 6/2021 ET Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Saturday Sunday ATL ET CEN MTN PAC NEWS NEWS NEWS 6:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 3:00 Rewind The Doc Project The Next Chapter NEWS NEWS NEWS 7:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 Quirks & The Next Now or Spark Unreserved Play Me Day 6 Quarks Chapter Never NEWS What on The Cost of White Coat NEWS World 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 8:00 Pop Chat WireTap Earth Living Black Art Report Writers & Company The House 8:37 NEWS World 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 9:00 World Report The Current Report The House The Sunday Magazine 10:00 NEWS NEWS NEWS 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 Day 6 q NEWS NEWS NEWS 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 11:00 Because News The Doc Project Because The Cost of What on Front The Pop Chat News Living Earth Burner Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 12:00 The Cost of Living 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 Rewind Quirks & Quarks What on Earth NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 Pop Chat White Coat Black Art 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 10:00 The Next Quirks & Unreserved Tapestry Spark Chapter Quarks Laugh Out Loud The Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 2:00 Ideas in 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 Podcast Now or CBC the Spark Now or Never Tapestry Playlist Never Music Live Afternoon NEWS NEWS NEWS 3:00 CBC 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 Writers & The Story Marvin's Reclaimed Music The Next Chapter Writers & Company Company From Here Room Top 20 World This Hr The Cost of Because What on Under the NEWS NEWS 4:00 WireTap 5:00 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 Living News Earth Influence Unreserved Cross Country Check- NEWS NEWS Up 5:00 The Current -

Appendix 6 Board of Directors’ Response to the Recommendations Presented in the Ombudsmens’ Report

APPENDIX 6 BOARD OF DIRECTORS’ RESPONSE TO THE RECOMMENDATIONS PRESENTED IN THE OMBUDSMENS’ REPORT BOARD OF DIRECTORS of the CANADIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION STANDING COMMITTEES ON ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANGUAGE BROADCASTING Minutes of the Meeting held on June 18, 2014 Ottawa, Ontario = by videoconference Members of the Committee present: Rémi Racine, Chairperson of the Committees Hubert T. Lacroix Edward Boyd Peter Charbonneau George Cooper Pierre Gingras Marni Larkin Terrence Leier Maureen McCaw Brian Mitchell Marlie Oden Members of the Committee absent: Cecil Hawkins In attendance: Maryse Bertrand, Vice-President, Real Estate, Legal Services and General Counsel Heather Conway, Executive Vice-President, English Services () Louis Lalande, Executive Vice-President, French Services () Michel Cormier, Executive Director, News and Current Affairs, French Services () Stéphanie Duquette, Chief of Staff to the President and CEO Esther Enkin, Ombudsman, English Services () Tranquillo Marrocco, Associate Corporate Secretary Jennifer McGuire, General Manage and Editor in Chief, CBC News and Centres, English Services () Pierre Tourangeau, Ombudsman, French Services () Opening of the Meeting At 1:10 p.m., the Chairperson called the meeting to order. 2014-06-18 Broadcasting Committees Page 1 of 2 1. 2013-2014 Annual Report of the English Services’ Ombudsman Esther Enkin provided an overview of the number of complaints received during the fiscal year and the key subject matters raised, which included the controversy about paid speaking engagements by CBC personalities, the reporting on results polls, the style of, and views expressed by, a commentator, questions relating to matters of taste, the coverage regarding the mayor of Toronto, and the website’s section for comments. She also addressed the manner in which non-news and current affairs complaints are being handled by the Corporation. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE EMBARGOED UNTIL JUNE 20, 2016 Film4Climate Global Video Competition Opens, In Search of Short Videos to Inspire the World Winners to be honored at official awards ceremony at COP22 climate summit in Marrakech, Morocco in November 2016 WASHINGTON, June 20, 2016 – The Film4Climate Global Video Competition formally opens today as the centerpiece of the Connect4Climate initiative to promote sustainability in the creative industries through active engagement with young people in finding solutions to climate change. Announced at the Cannes Film Festival by the World Bank Group’s Connect4Climate global partnership program, the competition will be open for submissions through September 15, with the winners to be announced at a high-profile awards ceremony at the United Nations COP22 Climate Summit in Marrakesh, Morocco in November. The winning entries will receive cash prizes of $8,000, $5,000, and $2,000 for first, second and third place in each of two categories: an under one-minute Public Service Advertisement (PSA) or a Short Film up to five minutes. The competition offers filmmakers a chance to have their work reviewed by a jury chaired by Bernardo Bertolucci, and including other preeminent directors, producers, writers and political leaders. At the competition’s announcement in Cannes, producer and jury member Lawrence Bender said, “In every country, every city, people have different stories on climate change...there are many stories that can be told. If this worldwide film competition creates a critical mass of ideas and energy, it could help tip the balance in terms of focusing people’s attention.” As the next five years will be critical to advancing and scaling up climate action around the world as part of the SDGs, the COP22 climate summit aims to encourage countries to implement ambitious climate actions, with youth playing a vital role in the agenda. -

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation's Annual Report For

ANNUAL REPORT 2001-2002 Valuable Canadian Innovative Complete Creative Invigorating Trusted Complete Distinctive Relevant News People Trust Arts Sports Innovative Efficient Canadian Complete Excellence People Creative Inv Sports Efficient Culture Complete Efficien Efficient Creative Relevant Canadian Arts Renewed Excellence Relevant Peopl Canadian Culture Complete Valuable Complete Trusted Arts Excellence Culture CBC/RADIO-CANADA ANNUAL REPORT 2001-2002 2001-2002 at a Glance CONNECTING CANADIANS DISTINCTIVELY CANADIAN CBC/Radio-Canada reflects Canada to CBC/Radio-Canada informs, enlightens Canadians by bringing diverse regional and entertains Canadians with unique, and cultural perspectives into their daily high-impact programming BY, FOR and lives, in English and French, on Television, ABOUT Canadians. Radio and the Internet. • Almost 90 per cent of prime time This past year, • CBC English Television has been programming on our English and French transformed to enhance distinctiveness Television networks was Canadian. Our CBC/Radio-Canada continued and reinforce regional presence and CBC Newsworld and RDI schedules were reflection. Our audience successes over 95 per cent Canadian. to set the standard for show we have re-connected with • The monumental Canada: A People’s Canadians – almost two-thirds watched broadcasting excellence History / Le Canada : Une histoire CBC English Television each week, populaire enthralled 15 million Canadian delivering 9.4 per cent of prime time in Canada, while innovating viewers, nearly half Canada’s population. and 7.6 per cent share of all-day viewing. and taking risks to deliver • The Last Chapter / Le Dernier chapitre • Through programming renewal, we have reached close to 5 million viewers for its even greater value to reinforced CBC French Television’s role first episode. -

CBC Radio One - New Brunswick Sept

CBC Radio One - New Brunswick Sept. 26, 2008 MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 5:00 CBC Radio Overnight 5:00 5:30 CBC Radio Overnight Daybreak 5:30 5:45 5:55 6:00 6:30 Weekend Mornings 6:30 Information Morning Weekend Mornings 7:00 CBC News: World 7:00 CBC News: World Report at 6/7/8 am CBC News: World Report 8/9 am 7:30 Report 7/8/9 am 7:30 8:00 8:00 8:30 Maritime Magazine 8:30 9:00 The Current* 9:00 The House* 9:30 9:30 10:00 10:00 The Sunday Edition 10:30 Q* GO!* 10:30 11:00 11:00 White Coat Black C'est la vie* Spark* Afghanada* Q* The Debaters 11:30 Art* 11:30 12:00 PM 12:00 PM Quirks & Quarks* Vinyl Café* 12:30 12:30 Maritime Noon 1:00 WireTap* 1:00 1:30 Definitely Not The The Inside Track 1:30 2:00 Opera* 2:00 Tapestry* 2:30 The Point* 2:30 3:00 3:00 The Next Chapter* Writers & Co. 3:30 3:30 4:00 Spark* 4:00 Shift All the Best White Coat Black Art* 4:30 CBC News: The World This Hour at 4/5 pm 4:30 5:00 5:00 Atlantic Airwaves 5:30 Cross Country 5:30 6:00 CBC News: The World at Six* Checkup 6:00 A Propos 6:30 6:30 As It Happens* 7:00 CBC News: The World This Weekend 7:00 Laugh Out Loud 7:30 Dispatches* Dispatches 7:30 8:00 The Night Time Review 8:00 8:30 The Debaters C'est La Vie 8:30 Outfront* Randy Bachman's Vinyl Tap 9:00 9:00 Ideas* Inside The Music 9:30 9:30 10:00 10:00 Q* 10:30 10:30 Saturday Night Blues In The Key of Charles 11:00 Quirks & Afghanada 11:00 Vinyl Cafe* Writers & Co.* 11:30 Quarks* WireTap* 11:30 From Our Own Vinyl Tap* 12:00 AM Correspondent And The Winner 12:00 AM The Choice* Rewind* The Ticket Is* 12:30 Culture Shock Tonic 12:30 1:00 1:00 CBC Radio Overnight 1:30 1:30 Returning favourite in a new time slot. -

How Does Greta Thunberg Use the Discourse of Youth in Her Movement For

UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Greta Effect: How does Greta Thunberg use the discourse of youth in her movement for climate justice? By Leann E. Leung Supervisors: Dr. Mél Hogan & Dr. Tamara Shepherd A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ARTS IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF “BA HONOURS COMMUNICATION AND MEDIA STUDIES” DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION, MEDIA AND FILM CALGARY, ALBERTA APRIL, 2020 © Leann E. Leung 2020 2 Abstract In Winter 2018, Greta Thunberg, a 15-year-old Swedish climate activist stopped going to school and started to protest outside of the Swedish Parliament with a sign that said, “Skolstrejk för Klimatet”, which stands for “Schoolstrike for Climate”. Fast forward to September 2019, with the help of social media, she led four million people around the world for the “Fridays4Future” global climate strike, and was named Time Magazine’s “Person of the Year” for 2019. Using the critical discourse analysis framework purposed by Fairclough and Janks, and drawing on Foucault’s theorization on discourse, power and resistance, this thesis analyzes three of Greta Thunberg’s speeches to understand the way she draws on different linguistic functions to form discursive frames about the identity and ideology of youth. Evidence from the analysis concludes that while Thunberg is politically resistant in her attempts to subvert the traditional social and familial hierarchies of power, she uses both dominant and counter discourses about youth to articulate her political position. The conclusion also suggests that the oppositional position of young people in the climate movement represents a counter-power, that mutually constitutes a power struggle along with the dominant power. -

Novel Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19): Q&A on Global Implications And

Novel Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19): Q&A on Global Implications and Responses April 17, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46319 SUMMARY R46319 Novel Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19): Q&A on April 17, 2020 Global Implications and Responses Tiaji Salaam-Blyther, On December 31, 2019, Chinese authorities informed the World Health Organization (WHO) Coordinator about a cluster of pneumonia cases in Wuhan City, Hubei Province. Illnesses have since been Specialist in Global Health linked to a disease caused by a previously unidentified strain of coronavirus, widely known as COVID-19. The disease quickly became a pandemic, and has spread to over 150 countries, including the United States. WHO declared the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on January 30, 2020, raised its global risk assessment to "Very High" on February 28, and labeled the outbreak a "pandemic" on March 11. In using the term pandemic, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus cited COVID-19's "alarming levels of spread and severity" and governments' "alarming levels of inaction." As of April 15, 2020, almost 2 million confirmed COVID-19 cases, and more than 120,000 confirmed deaths, of which over half of all cases and nearly 70% of all deaths were identified in Europe. Congress has demonstrated strong interest in ending the pandemic domestically and globally, having introduced 50 pieces of legislation on the matter (see the Appendix). Individual countries are carrying out not only domesitic but also international efforts to control the COVID-19 pandemic, with the WHO issuing guidance, coordinating some international research and related findings, and coordinating health aid in low-resource settings. -

A Journal of Policy Ideas from Across the Roosevelt Network

2020 A Journal of Policy Ideas from Across the Roosevelt Network | CREATIVE COMMONS COPYRIGHT 2018 | ROOSEVELTINSTITUTE.ORG | 1 Roosevet Network Staff KATIE KIRCHNER, NATIONAL DIRECTOR NICOLE ANNUNZIATA ANNA N. SMITH FERNANDA BORGES NOGUEIRA JADE WILENCHIK EAMON ROSS Student Leadership Policy Coordinators OLIVIA BRADY AUSTIN SHIRLEY SNIPTA MALLICK WITTER SWANSON ARIELLA MELTZER ANGELA TSAO DOMINICK PERAINO Roosevelt Institute Staff KENDRA BOZARTH TAYRA LUCERO MATT HUGHES KATY MILANI SUZANNE KAHN TIARA PEELE JULIETTE KANG STABLESKI VICTORIA STREKER KRISTINA KARLSSON Roosevelt Network Alumni ZACHARY AGUSH JOEL LUGONES CHISOLM ALLENLUNDY CASEY LUKSZO EMILY APPLE KIMBERLY MANRIQUEZ DON BLACK TARA MARLOWE SAUMYA BOLLAM SUNDUS MUJAHID JARRED BOWMAN SABA MUNDLAY STEPHANIE BRANOVAN VALERIE NAUMAN ASHLEY CHAPPO ALYSSA NUNEZ OLIVIA COHN AUSTIN PERELKA CHRISTINA COVER KEVIN POWERS NNEKA EWULONU CARLEY PRZYSTAC GRANT FEROWICH AMREEN RAHMAN COLLEEN FONSECA LILY ROBERTS JOHN FORD DOMINIC RUSSEL AMY FRIEDER SHAUNA RUST WILL GABELMAN CARA SCHIAVONE MIGUEL GALAZ JONATHAN SHERMAN MEHAK GUPTA GARRETT SHOR KEVIN HILKE ANDREW SMALLEY JAY HOBBS MANON STEEL COURTNEY JOLINE MICHELLE TAFUR BRIGID KENNEDY MICHAEL TRACHT ZACH KOMES MATT WALSH AMY LITTLETON PEGAH ZARDOOST HANNAH LOVE 2 | CREATIVE COMMONS COPYRIGHT 2018 | ROOSEVELTINSTITUTE.ORG | Who We Are The Roosevelt Network trains, develops, and supports emerging progressive policymakers, researchers, and advocates, focusing on communities historically denied political power. With locations on campuses and in cities in nearly 40 US states, the network is founded on the principle that changing who writes the rules can help fulfill the promise of American democracy and build true public power. The network supports student-led, scalable policy campaigns that fight for the equitable provision, distribution, and accessibility of public goods at the campus, local, and state levels. -

World Youth Report 2003

Economic & Social Affairs World ReportYOUTH 2003 The global situation of young people UNITED NATIONS Department of Economic and Social Affairs World ReportYOUTH 2003 The global situation of young people UNITED NATIONS Note The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat is a vital interface between global policies in the economic, social and environmental spheres and national action. The Department works in three main interlinked areas: (i) it compiles, generates and analyzes a wide range of eco- nomic, social and environmental data and information on which States Members of the United Nations draw to review common problems and to take stock of policy options; (ii) it facilitates the negotiations of Member States in many intergovernmental bodies on joint courses of action to address ongoing or emerging global challenges; and (iii) it advises interested Governments on the ways and means of translating policy frameworks developed in United Nations conferences and summits into programmes at the country level and, through techncal assistance, helps build national capacities. ST/ESA/287 ISBN 92-1-130228-5 United Nations publication - Sales No. E.03.IV.7 Copyright © United Nations, 2004 All rights reserved Printed by the United Nations Reproduction Section New York Young people make up almost a fifth of the world’s population. Close to 85 per cent of the 1.061 billion young men and women between the ages of 15 and 24 live in develop- ing countries; Asia accounts for the majority, with 60 per cent of the total, while another 15 per cent call Africa home, and approximate- ly 10 per cent reside in Latin America and the Caribbean. -

December 1, 2017 Filed Electronically Mr. Chris Seidl Secretary General

December 1, 2017 Filed Electronically Mr. Chris Seidl Secretary General Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0N2 Dear Mr. Seidl: Re: Broadcasting Notice of Consultation CRTC 2017-359: Call for comments on the Governor in Council’s request for a report on future programming distribution models The Writers Guild of Canada (WGC) is the national association representing approximately 2,200 professional screenwriters working in English-language film, television, radio, and digital media production in Canada. The WGC is actively involved in advocating for a strong and vibrant Canadian broadcasting system containing high-quality Canadian programming. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ES.1 The single most significant trend in the production, distribution, and consumption of audiovisual content today is the growth of online, primarily global (typically U.S.-based) Internet-based content services, and the associated impacts, largely negative, on traditional broadcasting services in Canada and, in turn, on the public policy tools associated with them. In our view, this is the primary, driving force of change in the audiovisual content sector, and virtually everything else that matters is some facet of this larger trend. ES.2 The report, Canadian Media in a Digital Universe, produced by Nordicity for the “Digital Media at the Crossroads” conference of January, 2016, and co-sponsored by the WGC, noted the following trends: One of the most significant shifts in the film and television industry is that today, video content is being produced at record levels and increasingly through a multitude of online channels. In tandem with the increased availability of content, viewing habits are also changing, in particular shifting from appointment television—e.g., over-the-air (OTA), specialty and pay TV—to on-demand and online channels, as well as binge-watching and multi- tasking. -

Communication for Climate Change Multi- Donor Trust Fund of the World Bank Group

Communication for Climate Change Multi- Donor Trust Fund of the World Bank Group Donor Report March 2013 - July 2016 INDEX Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 1 Support to Operations Highlights .............................................................................................. 1 Research & Capacity Building Highlights .................................................................................. 2 Advocacy and Fund Leveraging Highlights: Connect4Climate ................................................. 4 Advocacy Initiatives ............................................................................................................... 4 Mass Public Outreach activities ............................................................................................. 5 High-profile events ................................................................................................................. 5 Social Media Impact .............................................................................................................. 5 Summary Conclusion ................................................................................................................ 7 Trust Fund Context ..................................................................................................................... 9 The MDTF is organized in three components ........................................................................... 9 World Bank Climate