Violence Against Children WORLD REPORT on VIOLENCE AGAINST CHILDREN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

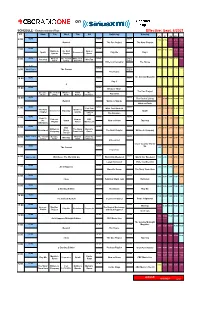

Siriusxm-Schedule.Pdf

on SCHEDULE - Eastern Standard Time - Effective: Sept. 6/2021 ET Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Saturday Sunday ATL ET CEN MTN PAC NEWS NEWS NEWS 6:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 3:00 Rewind The Doc Project The Next Chapter NEWS NEWS NEWS 7:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 Quirks & The Next Now or Spark Unreserved Play Me Day 6 Quarks Chapter Never NEWS What on The Cost of White Coat NEWS World 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 8:00 Pop Chat WireTap Earth Living Black Art Report Writers & Company The House 8:37 NEWS World 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 9:00 World Report The Current Report The House The Sunday Magazine 10:00 NEWS NEWS NEWS 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 Day 6 q NEWS NEWS NEWS 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 11:00 Because News The Doc Project Because The Cost of What on Front The Pop Chat News Living Earth Burner Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 12:00 The Cost of Living 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 Rewind Quirks & Quarks What on Earth NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 Pop Chat White Coat Black Art 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 10:00 The Next Quirks & Unreserved Tapestry Spark Chapter Quarks Laugh Out Loud The Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 2:00 Ideas in 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 Podcast Now or CBC the Spark Now or Never Tapestry Playlist Never Music Live Afternoon NEWS NEWS NEWS 3:00 CBC 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 Writers & The Story Marvin's Reclaimed Music The Next Chapter Writers & Company Company From Here Room Top 20 World This Hr The Cost of Because What on Under the NEWS NEWS 4:00 WireTap 5:00 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 Living News Earth Influence Unreserved Cross Country Check- NEWS NEWS Up 5:00 The Current -

Session 4 Personal Safety: Handling Taunting

Session 4 Personal Safety: Handling taunting/ bullying Rationale Children are often taunted and bullied by their peers, older children and at times by adults. They have a few ways of handling such incidents, ranging from retaliation, complaining to someone in authority, ignoring the taunts and at times, internalizing the damaging message. This can reduce a child’s self- esteem. We need to help children understand that words, like the deeds of a person, describe and tell others about the character and personality of the person doing the taunting. Materials required - Marker pen - Any sticking substance (Blu Tac / double sided sticking tape / cello tape / board pins) - Session 4- worksheets Objectives of session 4 To impart and help children internalize the following messages: Core message 1: The way a person talks and acts tells us about the character of that person. Core Message 2: My qualities and abilities are more important what people say about my looks. Core Message 3: We can help each other be safe Core message 4: It is okay to discuss embarrassing feelings with people who care for me. Core message 1: The way person talks and acts tells us about Material Required the character of that person. Marker pen, Blu Tac / Board pins / Double sided sticking tape / Cello tape Tell a story: Marker pen, Chalk, Duster, Blackboard Ashtavakra’s body was bent in eight places and hence he came to be known as ‘Ashtavakra’. His grandfather Uddalaka took up Tips for Trainers the responsibility of his education. Ashtavakra was brilliant and by the time he was 11 years old, he was a complete scholar. -

Workplace Bullying Made Simple Employee Quiz

Workplace Bullying Prevention Made Simple Facilitator’s Guide © TrainingABC 2011 Getting Started: Workplace bullying has been around for generations, however only just recently has the cost of this unfortunate tradition been quantified. Some experts estimate the cost of downtime and employee turnover as a result of bullying to run into the billions. In fact, most studies show that 50% of employees have either witnessed or been a victim of bullying at work. Workplace bullying of any type is truly unacceptable. Psychologists have compared the effects of bullying on victims as similar to post-traumatic stress disorder. The stress of bullying manifests into real physical and mental health issues. It destroys creativity by robbing some of the brightest employees of a voice in the organization. It increases employee turnover - bullied employees are three times more likely to leave a job than non-bullied employees. Lastly, it spreads like wildfire through organizations - destroying them from within. Bullying is like a virus – it spreads exponentially when it’s allowed to flourish. Stress the seriousness! The participants will key off you and decide if the organization is serious about stopping bullying. Put the participants at ease. Stress the seriousness of the topic. Be firm and don’t laugh or smile at jokes. Participants will key off of you! The Effects of Workplace Bullying Employee turnover Lost productivity Low company-wide morale Destroys creativity Cost to employee health Destroys organizational reputation Question: Ask the participant’s to list some of the effects of workplace bullying. What is Workplace Bullying? Bullying is hostile, aggressive or unreasonable behavior perpetrated against a co-worker. -

Louise Arbour and Marie Henein Share Their Personal Reflections on Unconscious Bias in Litigation December 9, 2020

Louise Arbour and Marie Henein Share Their Personal Reflections on Unconscious Bias in Litigation December 9, 2020 In this transformative age when actions against unconscious bias and social injustice have swiftly gathered momentum, two legal phenoms engage in an enlightening Q & A on what this means for us as people, as a profession, and as propellers for change. Hear Louise Arbour and Marie Henein tell us how they have approached unconscious bias and how to combat it. Topics will include the following: • personal experiences with power, privilege and unconscious bias • how to prevent bias and discrimination in workplaces • bias, discrimination and underrepresentation as viewed through a judicial lens • why the existence and consequences of unconscious bias are important to the bench and bar. Speakers The Honourable Louise Arbour, C.C., G.O.Q., Senior Counsel at Borden Ladner Gervais LLP The Honourable Louise Arbour is Senior Counsel and jurist in residence at BLG in Montreal. She provides strategic advice on litigation, governance and international disputes. She is an active mentor of younger lawyers. She recently completed her mandate at the UN as Special Representative of the Secretary- General on International Migration, which led to the adoption of the Global Compact for Migration. She has also held other senior positions at the United Nations, including High Commissioner for Human Rights (2004-2008) and Chief Prosecutor for The International Criminal Tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and for Rwanda (1996 to 1999). She formerly sat as a justice of the Supreme Court of Canada from 1999 to 2004, on the Court of Appeal for Ontario and the Supreme Court of Ontario. -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

Guidelines on Human Rights Education for Health Workers Published by the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) Ul

guidelines on human rights education for health workers Published by the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) Ul. Miodowa 10 00–251 Warsaw Poland www.osce.org/odihr © OSCE/ODIHR 2013 All rights reserved. The contents of this publication may be freely used and copied for educational and other non-commercial purposes, provided that any such reproduction is accompanied by an acknowledgement of the OSCE/ ODIHR as the source. ISBN 978-92-9234-870-0 Designed by Homework, Warsaw, Poland Cover photograph by iStockphoto Printed in Poland by Sungraf Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................ 5 FOreworD ................................................................................................... 9 Introduction ............................................................................................11 Rationale for human rights education for health workers............................. 11 Key definitions for the guidelines .............................................................................14 Process for elaborating the guidelines ................................................................... 15 Anticipated users of the guidelines .......................................................................... 17 Purposes of the guidelines ........................................................................................... 17 Application of the guidelines ......................................................................................18 -

Joking, Teasing Or Bullying? • a Kid Who Isn’T Very Nice to You Trips You in the Hall for the Third Time This Week

LESSON 2 It Takes One Unit Joking, Teasing Grade 2 • Ages 7-8 TIME FRAME or Bullying? Preparation: 15 minutes Instruction: 30-60 minutes Students will distinguish the difference MATERIALS between joking, teasing and bullying and Large white poster sheet divided understand how joking, teasing and bullying into three columns with the following headings: Joking, Teasing, Bullying can strengthen or weaken relationships. Create three signs, one that says “JOKING”, another that Lesson Background for Teachers says, “TEASING”, third that says “BULLYING”; post on different walls This lesson builds on previous lessons in this unit. before class For more information on bullying visit PrevNet, an anti-bullying organization that RAK journals provides research, information and resources. www.prevnet.ca Kindness Concept Posters for Assertiveness, Respect Key Terms for Students LEARNING STANDARDS Consider writing key terms on the board before class to introduce vocabulary and increase understanding. Common Core: CCSS.ELA-Literacy. SL.2.1, 1a-c, 2, 3 Colorado: Compre- JOKING To say funny things or play tricks on people to make them hensive Health S.4, GLE.3, EO.a-c; laugh. Joking is between friends, makes all people laugh, Reading, Writing and Communicating isn’t meant to be mean, cruel or unkind, doesn’t make S.1, GLE.1, EO.b-f; S.1, GLE.2, EO.a-c people feel bad and stops before someone gets upset. Learning standards key TEASING Teasing doesn’t happen often. It means to make fun of someone by playfully saying unkind and hurtful things to the person; it can be friendly, but can turn unkind quickly. -

Carissima Mathen*

C h o ic es a n d C o n t r o v e r sy : J udic ia l A ppointments in C a n a d a Carissima Mathen* P a r t I What do judges do? As an empirical matter, judges settle disputes. They act as a check on both the executive and legislative branches. They vindicate human rights and civil liberties. They arbitrate jurisdictional conflicts. They disagree. They bicker. They change their minds. In a normative sense, what judges “do” depends very much on one’s views of judging. If one thinks that judging is properly confined to the law’s “four comers”, then judges act as neutral, passive recipients of opinions and arguments about that law.1 They consider arguments, examine text, and render decisions that best honour the law that has been made. If judging also involves analysis of a society’s core (if implicit) political agreements—and the degree to which state laws or actions honour those agreements—then judges are critical players in the mechanisms through which such agreement is tested. In post-war Canada, the judiciary clearly has taken on the second role as well as the first. Year after year, judges are drawn into disputes over the very values of our society, a trend that shows no signs of abating.2 In view of judges’ continuing power, and the lack of political appetite to increase control over them (at least in Canada), it is natural that attention has turned to the process by which persons are nominated and ultimately appointed to the bench. -

Anti-Abuse, Violence and Harassment Policy

Policy No: HR-023 Group: HR Approved By: Board Executive Date: Oct. 13, 2015 OUR LADY SEAT OF WISDOM Ratified By: Board of Directors Date: Nov. 6, 2015 Amended By: Board of Directors Date: Feb. 6, 2016 Policy Title: Anti-Abuse, Violence and Harassment Policy Intent Our Lady Seat of Wisdom (OLSW) is committed to building and preserving a safe, productive and healthy environment for its students, employees, volunteers, visitors and contractors, based on mutual respect. In pursuit of this goal OLSW does not condone and will not tolerate any form of physical, sexual, emotional, verbal, or psychological abuse, neglect, violence or harassment/bullying against or by any OLSW employee, student, volunteer, visitor or contractor. Our Anti-Abuse, Violence and Harassment Policy is not intended to stop free speech or to interfere with everyday interactions. However, what one person finds offensive, others may not. Usually, abuse and harassment can be distinguished from normal, mutually acceptable socializing. It is important to remember that the perception of the receiver of the potentially offensive message be it spoken, a gesture, a picture or some other form of communication which may be deemed objectionable or unwelcome is of crucial importance. Nonetheless OLSW acknowledges that situations arise in which there is a perceived conflict between academic freedom and human rights. A violation of either freedom is of grave concern to the institution. With respect to the interplay of human rights protection and the practice of academic freedom, it is the position of OLSW that the responsible discussion of controversial issues in or out of the classroom is not a violation of this Policy. -

Human Rights International Ngos: a Critical Evaluation

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law University at Buffalo School of Law Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law Contributions to Books Faculty Scholarship 2001 Human Rights International NGOs: A Critical Evaluation Makau Mutua University at Buffalo School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/book_sections Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Makau Mutua, Human Rights International NGOs: A Critical Evaluation in NGOs and Human Rights: Promise and Performance 151 (Claude E. Welch, Jr., ed., University of Pennsylvania Press 2001) Copyright © 2001 University of pennsylvania Press. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of scholarly citation, none of this work may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher. For information address the University of Pennsylvania Press, 3905 Spruce Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Contributions to Books by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chapter 7 Human Rights International NGOs A Critical Evaluation Makau Mutua The human rights movement can be seen in variety of guises. It can be seen as a move ment for international justice or as a cultural project for "civilizing savage" cultures. -

Human Rights Organisations on 5 Continents

FIDH represents 164 human rights organisations on 5 continents FIDH - International Federation for Human Rights 17, passage de la Main-d’Or - 75011 Paris - France CCP Paris: 76 76 Z Tel: (33-1) 43 55 25 18 / Fax: (33-1) 43 55 18 80 www.fi dh.org ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT 2011 Cover: © AFP/MOHAMMED ABED Egypt, 16 December 2011. 04 Our Fundamentals 06 164 member organisations 07 International Board 08 International Secretariat 10 Priority 1 Protect and support human rights defenders 15 Priority 2 Promote and protect women’s rights 19 Priority 3 Promote and protect migrants’ rights 24 Priority 4 Promote the administration of justice and the i ght against impunity 33 Priority 5 Strengthening respect for human rights in the context of globalisation 38 Priority 6 Mobilising the community of States 43 Priority 7 Support the respect for human rights and the rule of law in conl ict and emergency situations, or during political transition 44 > Asia 49 > Eastern Europe and Central Asia 54 > North Africa and Middle East 59 > Sub-Saharan Africa 64 > The Americas 68 Internal challenges 78 Financial report 2011 79 They support us Our Fundamentals Our mandate: Protect all rights Interaction: Local presence - global action The International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) is an As a federal movement, FIDH operates on the basis of interac- international NGO. It defends all human rights - civil, political, tion with its member organisations. It ensures that FIDH merges economic, social and cultural - as contained in the Universal on-the-ground experience and knowledge with expertise in inter- Declaration of Human Rights. -

Appendix 6 Board of Directors’ Response to the Recommendations Presented in the Ombudsmens’ Report

APPENDIX 6 BOARD OF DIRECTORS’ RESPONSE TO THE RECOMMENDATIONS PRESENTED IN THE OMBUDSMENS’ REPORT BOARD OF DIRECTORS of the CANADIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION STANDING COMMITTEES ON ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANGUAGE BROADCASTING Minutes of the Meeting held on June 18, 2014 Ottawa, Ontario = by videoconference Members of the Committee present: Rémi Racine, Chairperson of the Committees Hubert T. Lacroix Edward Boyd Peter Charbonneau George Cooper Pierre Gingras Marni Larkin Terrence Leier Maureen McCaw Brian Mitchell Marlie Oden Members of the Committee absent: Cecil Hawkins In attendance: Maryse Bertrand, Vice-President, Real Estate, Legal Services and General Counsel Heather Conway, Executive Vice-President, English Services () Louis Lalande, Executive Vice-President, French Services () Michel Cormier, Executive Director, News and Current Affairs, French Services () Stéphanie Duquette, Chief of Staff to the President and CEO Esther Enkin, Ombudsman, English Services () Tranquillo Marrocco, Associate Corporate Secretary Jennifer McGuire, General Manage and Editor in Chief, CBC News and Centres, English Services () Pierre Tourangeau, Ombudsman, French Services () Opening of the Meeting At 1:10 p.m., the Chairperson called the meeting to order. 2014-06-18 Broadcasting Committees Page 1 of 2 1. 2013-2014 Annual Report of the English Services’ Ombudsman Esther Enkin provided an overview of the number of complaints received during the fiscal year and the key subject matters raised, which included the controversy about paid speaking engagements by CBC personalities, the reporting on results polls, the style of, and views expressed by, a commentator, questions relating to matters of taste, the coverage regarding the mayor of Toronto, and the website’s section for comments. She also addressed the manner in which non-news and current affairs complaints are being handled by the Corporation.