Novel Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19): Q&A on Global Implications And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

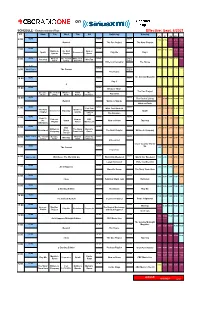

Siriusxm-Schedule.Pdf

on SCHEDULE - Eastern Standard Time - Effective: Sept. 6/2021 ET Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Saturday Sunday ATL ET CEN MTN PAC NEWS NEWS NEWS 6:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 3:00 Rewind The Doc Project The Next Chapter NEWS NEWS NEWS 7:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 Quirks & The Next Now or Spark Unreserved Play Me Day 6 Quarks Chapter Never NEWS What on The Cost of White Coat NEWS World 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 8:00 Pop Chat WireTap Earth Living Black Art Report Writers & Company The House 8:37 NEWS World 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 9:00 World Report The Current Report The House The Sunday Magazine 10:00 NEWS NEWS NEWS 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 Day 6 q NEWS NEWS NEWS 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 11:00 Because News The Doc Project Because The Cost of What on Front The Pop Chat News Living Earth Burner Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 12:00 The Cost of Living 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 Rewind Quirks & Quarks What on Earth NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 Pop Chat White Coat Black Art 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 10:00 The Next Quirks & Unreserved Tapestry Spark Chapter Quarks Laugh Out Loud The Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 2:00 Ideas in 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 Podcast Now or CBC the Spark Now or Never Tapestry Playlist Never Music Live Afternoon NEWS NEWS NEWS 3:00 CBC 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 Writers & The Story Marvin's Reclaimed Music The Next Chapter Writers & Company Company From Here Room Top 20 World This Hr The Cost of Because What on Under the NEWS NEWS 4:00 WireTap 5:00 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 Living News Earth Influence Unreserved Cross Country Check- NEWS NEWS Up 5:00 The Current -

Speaker Bios

SPEAKER BIOGRAPHIES The Honorable Deborah Birx, MD Deborah L. Birx, MD is Ambassador-at-Large and Coordinator of the United States government activities to combat HIV/AIDS globally. Ambassador Birx is a world-renowned medical expert and leader in the field of HIV/AIDS whose three decade-long career has focused on HIV/AIDS immunology, vaccine research, and global health. As the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator, Ambassador Birx oversees the implementation of the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), the largest commitment by any nation to combat a single disease in history, as well as all U.S. government engagement with the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria. In 1985, Ambassador Birx began her career with the Department of Defense (DoD) as a military trained clinician in immunology, focusing on HIV/AIDS vaccine research. From 1985-1989 she served as an Assistant Chief of the Hospital Immunology Service at Walter Reed Army Medical Center. Through her professionalism and leadership in the field, she progressed to serve as the Director of the U.S. Military HIV Research Program (USMHRP) at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research from 1996-2005. Ambassador Birx helped lead one of the most influential HIV vaccine trials in history (known as RV 144, or the Thai trial), which provided the first supporting evidence of any vaccine’s potential effectiveness in preventing HIV infection. During this time, she also rose to the rank of Colonel, bringing together the Navy, Army, and Air Force in a new model of cooperation – increasing the efficiency and effectiveness of the U.S. -

Notes from White House Briefing Call 6.10.2020

State, Local, and Tribal Leaders – Thank you to the State, local, and Tribal leaders who joined Vice President Mike Pence and Senior Administration Officials for the White House COVID-19 National Briefing Call on Wednesday, June 10. Attendees heard comprehensive updates and insights on continuing support for State, local, and Tribal response, recovery, and reopening efforts from Vice President Pence, Ambassador Deborah Birx (White House Coronavirus Task Force Coordinator), Secretary Ben Carson (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development), Secretary Eugene Scalia (U.S. Department of Labor), and Secretary Betsy DeVos (U.S. Department of Education). The Vice President also expressed his appreciation for the great work and sacrifice from America’s State, local, and Tribal leaders and also asked call attendees to share his, President Trump’s, and the entire Administration’s appreciation for our Nation’s first responders and healthcare workers. Find several examples from State and local leaders here, here, here, here, and here. Below, please find pertinent updates and a recap from the call. Recent Announcements President Trump Hosts Law Enforcement Roundtable: On Monday, President Trump held a roundtable discussion with law enforcement officials at the White House, where officers discussed responsible ideas for reform and ways for police officers to act as better friends for their communities. “There’s a reason for our less crime – it’s because we have great law enforcement. I’m very proud of them. There won’t be defunding, there won’t be dismantling of our police, and there are not going to be any disbanding of our police,” the President stated. -

COVID-19: a Weekly Health Care Update from Washington April 13-17, 2020

COVID-19: A Weekly Health Care Update from Washington April 13-17, 2020 IN BRIEF What Happened This Week: Negotiators failed to reach consensus on a proposal to provide additional support for small businesses this week (hospital funding was one of the major sticking points, although negotiations are progressing). Meanwhile, at the White House, President Trump and members of the Coronavirus Task Force unveiled the details of a new phased approach to “reopen” the nation’s the economy yesterday and instructed state governors to take the lead. What to Expect in the Weeks and Months Ahead: Expect lawmakers to continue negotiating a path forward for additional small business support; expect lawmakers to continue working remotely on additional measures tied to the pandemic; and expect the Trump Administration to continue providing clarity and guidance on the distribution of funds and implementation of other major provisions in the first three COVID-19 bills. DEEP DIVE President Trump Unveils “Guidelines for Opening Up America Again”; Instructs State Governors to Take the Lead on a Phased Reopening of the Economy President Trump and members of the White House Coronavirus Task Force unveiled the details of a new phased “reopening” of the nation’s economy using a “deliberate, data-driven approach.” The Administration leaves much of the decision-making to the states but instructs them to open up gradually after benchmarks on new cases, testing, and hospital resources are met. As far as timing goes, Coronavirus Task Force Response Coordinator Dr. Deborah Birx said there is no set schedule for any of the guideline’s three phases. -

Appendix 6 Board of Directors’ Response to the Recommendations Presented in the Ombudsmens’ Report

APPENDIX 6 BOARD OF DIRECTORS’ RESPONSE TO THE RECOMMENDATIONS PRESENTED IN THE OMBUDSMENS’ REPORT BOARD OF DIRECTORS of the CANADIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION STANDING COMMITTEES ON ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANGUAGE BROADCASTING Minutes of the Meeting held on June 18, 2014 Ottawa, Ontario = by videoconference Members of the Committee present: Rémi Racine, Chairperson of the Committees Hubert T. Lacroix Edward Boyd Peter Charbonneau George Cooper Pierre Gingras Marni Larkin Terrence Leier Maureen McCaw Brian Mitchell Marlie Oden Members of the Committee absent: Cecil Hawkins In attendance: Maryse Bertrand, Vice-President, Real Estate, Legal Services and General Counsel Heather Conway, Executive Vice-President, English Services () Louis Lalande, Executive Vice-President, French Services () Michel Cormier, Executive Director, News and Current Affairs, French Services () Stéphanie Duquette, Chief of Staff to the President and CEO Esther Enkin, Ombudsman, English Services () Tranquillo Marrocco, Associate Corporate Secretary Jennifer McGuire, General Manage and Editor in Chief, CBC News and Centres, English Services () Pierre Tourangeau, Ombudsman, French Services () Opening of the Meeting At 1:10 p.m., the Chairperson called the meeting to order. 2014-06-18 Broadcasting Committees Page 1 of 2 1. 2013-2014 Annual Report of the English Services’ Ombudsman Esther Enkin provided an overview of the number of complaints received during the fiscal year and the key subject matters raised, which included the controversy about paid speaking engagements by CBC personalities, the reporting on results polls, the style of, and views expressed by, a commentator, questions relating to matters of taste, the coverage regarding the mayor of Toronto, and the website’s section for comments. She also addressed the manner in which non-news and current affairs complaints are being handled by the Corporation. -

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation's Annual Report For

ANNUAL REPORT 2001-2002 Valuable Canadian Innovative Complete Creative Invigorating Trusted Complete Distinctive Relevant News People Trust Arts Sports Innovative Efficient Canadian Complete Excellence People Creative Inv Sports Efficient Culture Complete Efficien Efficient Creative Relevant Canadian Arts Renewed Excellence Relevant Peopl Canadian Culture Complete Valuable Complete Trusted Arts Excellence Culture CBC/RADIO-CANADA ANNUAL REPORT 2001-2002 2001-2002 at a Glance CONNECTING CANADIANS DISTINCTIVELY CANADIAN CBC/Radio-Canada reflects Canada to CBC/Radio-Canada informs, enlightens Canadians by bringing diverse regional and entertains Canadians with unique, and cultural perspectives into their daily high-impact programming BY, FOR and lives, in English and French, on Television, ABOUT Canadians. Radio and the Internet. • Almost 90 per cent of prime time This past year, • CBC English Television has been programming on our English and French transformed to enhance distinctiveness Television networks was Canadian. Our CBC/Radio-Canada continued and reinforce regional presence and CBC Newsworld and RDI schedules were reflection. Our audience successes over 95 per cent Canadian. to set the standard for show we have re-connected with • The monumental Canada: A People’s Canadians – almost two-thirds watched broadcasting excellence History / Le Canada : Une histoire CBC English Television each week, populaire enthralled 15 million Canadian delivering 9.4 per cent of prime time in Canada, while innovating viewers, nearly half Canada’s population. and 7.6 per cent share of all-day viewing. and taking risks to deliver • The Last Chapter / Le Dernier chapitre • Through programming renewal, we have reached close to 5 million viewers for its even greater value to reinforced CBC French Television’s role first episode. -

What You Need to Know | President Trump's

From: Caliguiri, Laura To: Kimberly, Brad; Lynch, Sarah; Capobianco, Abigail Subject: FW: What You Need To Know | President Trump’s Coronavirus Response Efforts Date: Tuesday, March 31, 2020 8:53:05 PM From: Mitchell, Austin A. EOP/WHO (b) (6)@who.eop.gov> Sent: Tuesday, March 31, 2020 8:51 PM Subject: What You Need To Know | President Trump’s Coronavirus Response Efforts What You Need To Know | President Trump’s Coronavirus Response Efforts ________________________________ President Trump and his Administration are working every day to protect the health and wellbeing of Americans and respond to the coronavirus. WHOLE-OF-GOVERNMENT APPROACH The President signed the CARES Act, providing unprecedented and immediate relief to American families, workers, and businesses. President Trump declared a national emergency, inviting States, territories, and tribes to access over $42 billion in existing funding. President Trump signed initial legislation securing $8.3 billion for coronavirus response. President Trump signed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, ensuring that American families and businesses impacted by the virus receive the strong support they need. To leverage the resources of the entire government, the President created a White House Coronavirus Task Force to coordinate response. The Vice President named Dr. Deborah Birx to serve as the White House Coronavirus Response Coordinator. At the request of President Trump, FEMA is leading federal operations on behalf of the White House Coronavirus Task Force. FEMA’s National Response Coordination Center has been activated to its highest level in support of coronavirus response. The President held a teleconference with other G20 leaders to coordinate coronavirus response. -

COVID-19 Response – Weekly Wrap-Up

COVID-19 Response – Weekly Wrap-up APRIL 24, 2020 – 2:00 PM CONGRESS COVID news… Congress passed, and the President signed, the Paycheck Protection Program and Healthcare Enhancement Act, which increases the funding levels for programs that were expanded or authorized under the CARES Act, as well as some additional provisions. A link to the VNF Alert on the measure is here. Additionally, the House passed, along party lines, a resolution establishing an investigative oversight committee that will oversee the implementation of the CARES Act and the associated economic recovery in the post-COVID-19 landscape. Democrats released proposed changes to House rules that would allow Members of Congress to vote by proxy for the first time in U.S. history, but the proposal was quickly sidelined after objections mounted from Republicans, who were not consulted on the proposed changes. Visit our COVID-19 Resource Center Lawmakers will now turn to further recovery and stimulus measures. Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) and other Democrats are calling for swift action legislation to provide aid to state and local governments, a potential second round of stimulus checks to citizens, funding for expanded health care coverage for recently laid-off workers, COVID-related expansions to Occupational Safety and Health Administration rules, money for mail-in voting in the November elections and additional funding to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) and other Republicans have called for discussions on any future bill to occur only when lawmakers return to Washington, which currently is slated for the week of May 4. -

Dân Chúa on Line Số 67 - Tháng 1.2021 Nguyệt San Công Giáo Trong Số Này Katholische on Line

Dân Chúa on line số 67 - tháng 1.2021 Nguyệt San Công Giáo Trong Số Này Katholische on line . Lá Thư Chủ Nhiệm. Monthly Catholic on line . Lịch Phụng vụ tháng Một 2021. Email: [email protected] . Năm Mục vụ Giới Trẻ 2021. Herausgeber: Franz Xaver e.V. Ghen và ghét. Dân Chúa Katholische on line . Khi Nào Trẻ Em DÂN CHÚA ÂU CHÂU Có Thể Chích Ngừa Covid-19? Chủ nhiệm: Lm Stêphanô Bùi Thượng Lưu . Những Ai Đã Góp Phần Sáng Chế Phụ tá chủ nhiệm: Lm Paul Đào Văn Thạnh Thuốc Ngừa Covid-19?. Thư ký : Sr. Anne Marie Nguyễn Thị Hường . Khát vọng Hòa Bình. Chủ biên thần học : Lm Vincent Lê Phú Hải omi . Đánh giá đời sống thiêng liêng Chủ biên văn hóa: Sh Bonaventure Trần Công Lao qua 4 điểm cốt yếu. hình bìa : Trần Anh Dũng omi. Một năm đặc biệt để làm chứng DÂN CHÚA ÚC CHÂU cho tình yêu gia đình. 715 Sydney Rd. Brunswick, Victoria 3056 . Loài Người Đã Được Tạo Dựng Tel.: (03) 9386-7455 / Fax: (03) 9386-3326 Hay Do Tiến Hóa?. Chủ nhiệm: Lm. Nguyễn Hữu Quảng SDB . Nguồn gốc vũ trụ theo Thánh Kinh Chủ bút: Rev. James Võ Thanh Xuân và khoa học. Phụ tá Chủ bút: Trần Vũ Trụ . Thiên Chúa Sáng Tạo Vũ Trụ Tổng Thư Ký: Sr. Nguyễn Thùy Linh, FMA Và Con Người. Ban kỹ thuật: Hiệp Hải . Trái đất có thể khóc không?. NHÀ KHẢO CỔ NGƯỜI ANH TIN RẰNG Mục đích & Tôn CHỈ Dân Chúa ÔNG ĐÃ TÌM THẤY NGÔI NHÀ Mục đích: Góp phần vào việc phục vụ tập thể Công THỜI THƠ ẤU CỦA CHÚA GIÊSU Giáo Việt Nam và đồng bào để cùng thăng tiến toàn . -

White House Briefing Call Notes 7.8.2020

Office of Intergovernmental Affairs State, Local, and Tribal Leaders – Thank you to the State, local, and Tribal leaders who joined for the White House COVID-19 National Briefing Call on Wednesday, July 8. Attendees heard comprehensive updates and insights on continuing support for State, local, and Tribal response, recovery, and reopening efforts from Larry Kudlow (Assistant to the President for Economic Policy), Secretary Robert Wilkie (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs), Ambassador Deborah Birx (White House Coronavirus Task Force Coordinator), U.S. Surgeon General Gerome Adams, Deputy Surgeon General Erica Schwartz, and Assistant Secretary Frank Brogan (U.S. Department of Education). Below, please find pertinent announcements from across the Federal family and a brief recap of yesterday's call, including information and guidance from the White House Summit on Reopening America’s Schools. We would also like to flag CDC’s online testing resource page where you can find up-to-date testing information. Recent Announcements Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) Extended Through August: On July 4, President Trump signed legislation (S. 4116) reauthorizing the Paycheck Protection Program through August 8, 2020. Enacted in March as part of the CARES Act, the $669 billion program has approved more than 4.8 million loans totaling more than $520 billion and supporting over 51 million jobs to date. The extension of the program through August will make available the remaining $134 billion to small businesses and qualifying entities. Learn more about the PPP here. Department of the Treasury’s OIG released reporting requirements for CRF recipients: On July 2, Department of the Treasury’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) released a memorandum with instructions for recipients of the CARES Act’s Coronavirus Relief Fund (CRF). -

From May 14 to 17, 2021, Data for Progress Conducted a Survey of 1,203 Registered Voters Nationally Using Web Panel Respondents

From May 14 to 17, 2021, Data for Progress conducted a survey of 1,203 registered voters nationally using web panel respondents. The sample was weighted to be representative of the adult population in the United States by age, gender, education, and race. The survey was conducted in English. The margin of error is ±3 percentage points. N=1203 unless otherwise specified. Some values may not add up to 100 due to rounding. D I R [1] Below is a list of people, groups, or institutions that are .V .e .r y. .f .a .v .o .r a. .b .l e. 3. 7. %. 6. 1. .% . 3. 0. %. 1. 3. involved in the response to the coronavirus pandemic. For .S .o .m . e. w. .h . a. t. f.a . v.o . r.a .b . l.e . 1. 9. 1. 9. 1. 7. 1. 9. each, say whether you have a favorable or unfavorable view: .S .o .m . e. w. .h . a. t. u. n. .f a. v. o. r. a. b. l.e . 1. 1. 5. 1. 8. 1. 4. -- Dr. Anthony Fauci .V .e .r y. .u . n. f.a .v .o .r .a .b .l e. 2. 0. 3. 1. 6. 4. 4. .H .a .v .e .n . '.t .h .e .a .r .d . e. n. .o .u .g .h . .t o. .s .a .y . 1. 3. 1. 2. 2. 0. 1. 0. .F A. .V .O . R. A. .B .L .E . (.T .O . T. .A .L .) . 5. 6. %. 8. 0. .% . 4. 7. %. 3. 2. .U .N . F. A. -

Introduction

Timeline - Covad-19 Virus and related events. There are five sections to this document. The timeline is the main section, but the others are also in timeline order providing supporting information. 1. Timeline of notable events. 2. Other related links. 3. Reported statistics and studies. 4. Comparisons with other medical events a. Comparisons with the 1918 Flu b. Comparisons with the 2009 H1N1 pandemic c. Comparisons with the 2018-2019 Flu Season CDC data 5. Comments and observations. Introduction The Wuhan/Chinese/Covid19 virus event is a fast moving and daily confusing combination of sound bites, often shared to make the speaker look better. This timeline is an attempt to keep the events in order, and to shed some comparative light on all the data being shared. The 1918 Influenza pandemic killed an estimated 675,000 people in the United States for a mortality rate of 636/100,000. As of Aug 25, 2021, the Wuhan Covid-19 virus has reportedly involved in the death of 628.579 people in the United States for a mortality rate of 191/100,000. The 1918 event therefore was 3 (times) times worse at 636/100,000 that this illness. Of note is the Covid-19 death numbers are likely artificially larger than actual for two reasons. First, Congress paid a 20% bounty for including a Covid-19 any diagnosis, and second on March 24, 2020 the CDC directed this “COVID-19 should be reported on the death certificate for all decedents where the disease caused or is assumed to have caused or contributed to death”.