An Exploratory Study of the Problem Solving Strategies Used by Selected Young Adolescents While Playing a Microcomputer Text Adventure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ye Intruders Beware: Fantastical Pirates in the Golden Age of Illustration

YE INTRUDERS BEWARE: FANTASTICAL PIRATES IN THE GOLDEN AGE OF ILLUSTRATION Anne M. Loechle Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of the History of Art Indiana University November 2010 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee _________________________________ Chairperson, Sarah Burns, Ph.D. __________________________________ Janet Kennedy, Ph.D. __________________________________ Patrick McNaughton, Ph.D. __________________________________ Beverly Stoeltje, Ph.D. November 9, 2010 ii ©2010 Anne M. Loechle ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii Acknowledgments I am indebted to many people for the help and encouragement they have given me during the long duration of this project. From academic and financial to editorial and emotional, I was never lacking in support. I am truly thankful, not to mention lucky. Sarah Burns, my advisor and mentor, supported my ideas, cheered my successes, and patiently edited and helped me to revise my failures. I also owe her thanks for encouraging me to pursue an unorthodox topic. From the moment pirates came up during one of our meetings in the spring of 2005, I was hooked. She knew it, and she continuously suggested ways to expand the idea first into an independent study, and then into this dissertation. My dissertation committee – Janet Kennedy, Patrick McNaughton, and Beverly Stoeltje – likewise deserves my thanks for their mentoring and enthusiasm. Other scholars have graciously shared with me their knowledge and input along the way. David M. Lubin read a version of my third chapter and gave me helpful advice, opening up to me new ways of thinking about Howard Pyle in particular. -

Pirates and Perils of the Deep! Chatterbooks Activity Pack

Pirates and Perils of the Deep! Chatterbooks Activity Pack Pirates and Perils of the Deep! Reading and activity ideas for your Chatterbooks group About this pack Ahoy, me Hearties – and shiver me timbers! Here be a Chatterbooks pack full of swashbuckling pirate fun – activity ideas and challenges, and great reading for your group! The pack is brought to you by The Reading Agency and their publisher partnership Children’s Reading Partners Chatterbooks [ www.readinggroups.org/chatterbooks] is a reading group programme for children aged 4 to 14 years. It is coordinated by The Reading Agency and its patron is author Dame Jacqueline Wilson. Chatterbooks groups run in libraries and schools, supporting and inspiring children’s literacy development by encouraging them to have a really good time reading and talking about books. The Reading Agency is an independent charity working to inspire more people to read more through programmes for adults, young people and Children – including the Summer Reading Challenge, and Chatterbooks. See www.readingagency.org.uk Children’s Reading Partners is a national partnership of children’s publishers and libraries working together to bring reading promotions and author events to as many children and young people as possible. Contents 2 Things to talk about 2 Activity ideas 8 Chatterbooks double session plan, with a pirates theme 10 Pirates and perils quiz 11 Pirates and perils: great titles to read 17 More swashbuckling stories For help in planning your Chatterbooks meeting, have a look at these Top Tips for a Successful Session 2 Pirates and Perils of the Deep! Chatterbooks Activity Pack Ideas for your Chatterbooks sessions Things to talk about What do you know about pirates? Get together a collection of pirate books – stories and non-fiction – so you’ve got lots to refer to, and plenty of reading for your group to share. -

TREASURE ISLAND the NOVEL and the MUSICAL 2 STUDY MATERIALS

Maine State Music Theatre Curtis Memorial Library, Topsham Public Library, and Patten Free Library present A STUDY GUIDE TO TREASURE ISLAND The NOVEL and the MUSICAL 2 STUDY MATERIALS TREASURE ISLAND: THE NOVEL Robert Louis Stevenson Page 3 Treasure Island in Literary History Page 5 Fun Facts About the Novel Page 6 Historical Context of the Novel Page 7 Adaptations of Treasure Island on Film and Stage Page 9 Treasure Island: Themes Page 10 Treasure Island: Synopsis of the Novel Page 11 Treasure Island: Characters in the Novel Page 13 Treasure Island: Glossary Page 15 TREASURE ISLAND A Musical Adventure: THE ROBIN & CLARK MUSICAL Artistic Statement Page 18 The Creators of the Musical Page 19 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Themes Page 20 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Synopsis & Songs Page 21 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Cast of Characters Page 24 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: World Premiere Page 26 Press Quotes Page 27 QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION Page 28 MSMT’s Treasure Island A Musical Adventure Page 29 3 TREASURE ISLAND: THE NOVEL ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, on November 13, 1850, to Thomas and Margaret Stevenson. Lighthouse design was his father's and his family's profession, so at age seventeen, he enrolled at Edinburgh University to study engineering, with the goal of following in the family business. Lighthouse design never appealed to Stevenson, though, and he began studying law instead. His spirit of adventure truly began to appear at this stage, and during his summer vacations he traveled to France to be around young writers and painters. -

A History of the Personal Computer Index/11

A History of the Personal Computer 6100 CPU. See Intersil Index 6501 and 6502 microprocessor. See MOS Legend: Chap.#/Page# of Chap. 6502 BASIC. See Microsoft/Prog. Languages -- Numerals -- 7000 copier. See Xerox/Misc. 3 E-Z Pieces software, 13/20 8000 microprocessors. See 3-Plus-1 software. See Intel/Microprocessors Commodore 8010 “Star” Information 3Com Corporation, 12/15, System. See Xerox/Comp. 12/27, 16/17, 17/18, 17/20 8080 and 8086 BASIC. See 3M company, 17/5, 17/22 Microsoft/Prog. Languages 3P+S board. See Processor 8514/A standard, 20/6 Technology 9700 laser printing system. 4K BASIC. See Microsoft/Prog. See Xerox/Misc. Languages 16032 and 32032 micro/p. See 4th Dimension. See ACI National Semiconductor 8/16 magazine, 18/5 65802 and 65816 micro/p. See 8/16-Central, 18/5 Western Design Center 8K BASIC. See Microsoft/Prog. 68000 series of micro/p. See Languages Motorola 20SC hard drive. See Apple 80000 series of micro/p. See Computer/Accessories Intel/Microprocessors 64 computer. See Commodore 88000 micro/p. See Motorola 80 Microcomputing magazine, 18/4 --A-- 80-103A modem. See Hayes A Programming lang. See APL 86-DOS. See Seattle Computer A+ magazine, 18/5 128EX/2 computer. See Video A.P.P.L.E. (Apple Pugetsound Technology Program Library Exchange) 386i personal computer. See user group, 18/4, 19/17 Sun Microsystems Call-A.P.P.L.E. magazine, 432 microprocessor. See 18/4 Intel/Microprocessors A2-Central newsletter, 18/5 603/4 Electronic Multiplier. Abacus magazine, 18/8 See IBM/Computer (mainframe) ABC (Atanasoff-Berry 660 computer. -

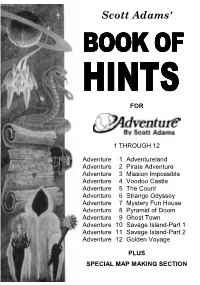

Scott Adams' BOOK of HINTS FOR

Scott Adams' BOOK OF HINTS FOR 1 THROUGH 12 Adventure 1 Adventureland Adventure 2 Pirate Adventure Adventure 3 Mission Impossible Adventure 4 Voodoo Castle Adventure 5 The Count Adventure 6 Strange Odyssey Adventure 7 Mystery Fun House Adventure 8 Pyramid of Doom Adventure 9 Ghost Town Adventure 10 Savage Island-Part 1 Adventure 11 Savage Island-Part 2 Adventure 12 Golden Voyage PLUS SPECIAL MAP MAKING SECTION THE FOLLOWING IS A METHOD USEFUL IN MAPPING ADVENTURES Each room is represented by a box with the name of the room in it, and all original items found in it noted alongside. FOREST Directions from a location are indicated by a line coming out of anywhere on the box, but with the direction leaving the box indicated by the first letter of that direction. GROVE GROVE The above shows it is East from the grove to the swamp and West from the swamp to the grove. In the case of being able to go only in one direction, an arrow is put at the end of the path. FOREST GROVE GROVE This indicates that upon leaving the grove you go north to the forest, but that you cannot return! The best way to use this system is that, upon entering a location, you draw a line representing each possible exit and its location. Later you connect them to rooms as you continue your exploration. FOREST MEADOW GROVE GROVE The advantage is that you will not forget to explore an exit once you get past your initial probe. Another advantage of this system is that you never need redraw your map as you stick extra locations anywhere on your paper. -

Arlecchino's Pirate Adventure

Arlecchino’s Pirate Adventure By Craig Lee Performance Rights It is an infringement of the federal copyright law to copy or reproduce this script in any manner or to perform this play without royalty payment. All rights are controlled by Eldridge Publishing Co., Inc. Contact the publisher for additional scripts and further licensing information. The author’s name must appear on all programs and advertising with the notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Eldridge Publishing Company.” ELDRIDGE PUBLISHING COMPANY © 2018 by Craig Lee Download your complete script from Eldridge Publishing https://histage.com/arlecchinos-pirate-adventure Arlecchino’s Pirate Adventure - 2 - DEDICATION To Katy, Mackenzie and Zoe. For making my life full of lazzi’s. STORY OF THE PLAY Inspired by Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, this adventure follows a commedia troupe as they travel from kingdom to kingdom to present their plays. Unfortunately, Arlecchino has misplaced the map and now they are lost. While looking for the map, they are overrun by pirates searching for buried treasure. Now Arlecchino and his friends are in danger and may have to walk the plank. It’s up to Arlecchino to save his friends! SYNOPSIS Arlecchino, the crafty trickster, always has his head in the clouds. He doesn’t want to do any work or take any responsibility. He would rather pretend he’s an adventurous pirate on the high seas or on a remote island looking for buried treasure. Today he is leading his commedia friends to the Kingdom of Isola del Tesoro to present their play. Unfortunately, he’s lost the map! Now they are lost and only have a few hours to get to the kingdom. -

Year 3 Fortnightly Online Learning Monday 1St June

st th Year 3 fortnightly online learning Monday 1 June – Friday 13 June. Here are some activities and ideas that you may want to explore and enjoy. Please just use them to fit into your own routine, as we appreciate that all families have different circumstances at the moment. Take photos if you wish and send them to our year group email. Please only do what you can, when you can, and if you have the resources to do so. The most important thing is to take care of each other, have some fun and family time and stay safe. Thinking of you all! Mrs Barnes Pirate Research Treasure Island Adventure Wanted Poster -Can you find out about any real-life pirates? -Pirates used maps to hide and find treasure. Can you create A wanted poster was made to let everyone know your own treasure map? Think about what will be on your Who were they? What did they do? about a pirate who had committed crime. Can you -Try using this link to find out about some map (hills, swamps, trees, rivers, bridge, bones, cave). Make make your own ‘Wanted’ poster with details of a very interesting pirates, including Black your map as interesting as you can. Can you use a grid with pirate? Don’t forget to include a picture of what the co-ordinates on your map? How could you make the paper Beard, born in 1680, who was thought to be pirate looks like, with details of what he/she has done look old? Try rubbing a wet tea bag over the paper and then wrong. -

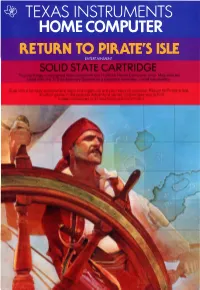

TEXAS INSTRUMENTS HOME COMPUTER RETURN to PIRATE's ISLE Entertal NMENT Adventure #14 Return to Pirate's Isle

TEXAS INSTRUMENTS HOME COMPUTER RETURN TO PIRATE'S ISLE ENTERTAl NMENT Adventure #14 Return To Pirate's Isle Programmed by: Scott Adams Book developed and written by: Staff members of Texas Instruments Instructional Communications. Copyright© 1983 by Texas Instruments Incorporated. Solid State Cartridge program and data base contents copyright© 1983 by Scott Adams. See important warranty information at back of book. The World of Adventure The world of Adventure takes you to To help you select your next many exotic locations. In each Adventure, here is a brief summary Adventure you face unexpected of the Adventures currently danger as you carry out your available. mission. Whether your goal is to explore a mysterious pyramid or escape from a savage jungle, your reasoning power is challenged at every turn. Pirate's Adventure The Count Your adventure begins in a flat in In The Count, you wake from a nap to London, but you soon find yourself on a find yourself in a strange bed holding a strange island filled with treasure. tent stake. Now it's up to you to Explore it thoroughly and make friends discover who you are, what you are with its inhabitants, whose help you doing in Transylvania, and why the need for success. postman delivered a bottle of blood. Adventureland Strange Odyssey The Adventureland game begins in the Your Strange Odyssey begins as you forest of an enchanted world. By realize that you are stranded on a small exploring this world, you can locate 13 planetoid and must repair your ship treasures, as well as the special place before you can go home. -

Stevenson's Treasure Island

:. (e Ifta^uM &ava*Zz^/£4t&sT^(yi^\754 9K\S 7aejt—iSt.e/l CfWif. '/art'tue/f o^3 'a+^&ns \^ <z - STEVENSON'S TREASURE ISLAND Edited with Introduction and Notes by «? G& FRANK WILSON CHENEY HERSEY, A.M. <@ W Instructor in English in Harvard University, Coeditor of "Specimens of Prose Composition" and "Representa- tive Biographies of English Men of Letters" ( J GINN AND COMPANY BOSTON • NEW YORK • CHICAGO LONDON ATLANTA • DALLAS • COLUMBUS • SAN FRANCISCO • . •,-... • • • • - . < . - • COPYRIGHT, 191 1, BY GINN AND COMPANY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 324.5 off* vnhmm EDUCATION DEFT. GINN AND COMPANY • PRO- PRIETORS • BOSTON • U.S.A. PREFACE " " Ogilvy," I remember," says Sir J. M. Barrie in Margaret " a delightful life of his mother, I remember how she read { Treasure Island,' holding it close to the ribs of the fire (because she could not spare a moment to rise and light the gas), and how, when bedtime came, and we coaxed, remon- strated, scolded, she said quite fiercely, clinging to the book, 1 1 dinna lay my head on a pillow this night till I see how that laddie got out of the barrel.' " This is the spirit in which "Treasure Island" should be read. The student should first be allowed to give himself up to the enjoyment of rapidly reading the story as a story. He may then turn to various parts of the Introduction and the Notes, which are designed to sharpen his appreciation and zest. Several sections of the Introduction have been included in order that the student may have immediately at hand material which hardly any school library possesses: for instance, a history of the Buccaneers ; many quotations from Captain Charles Johnson's " History of the Pyrates," which Stevenson used in writing his story; and extracts from Stevenson's essay " A Gossip on Romance." Further- more, the explanation of sailing a schooner is inserted for the benefit of the many students who, living inland, have no experience in sailing and no knowledge of seamanship. -

Pirate Ship Anchored Just Off the Beach

Teacher’s Notes Pearson EnglishTeacher’s Kids Readers Notes Pearson English Kids Readers Level 4 Suitable for: young learners who have completed up to 200 hours of study in English Type of English: American Headwords: 800 Key words: 15 (see pages 2 and 7 of these Teacher’s Notes) Key grammar: past simple of regular and irregular verbs, irregular superlatives (best, worst), How + adjective, relative pronouns, conjunctions Background information – The world Summary of the story of Poptropica English One sunny day, best friends Max and Clara Poptropica English has six islands, where the see a pirate ship anchored just off the beach. students can follow stories to explore and discover They discover that a castle and a volcano have English and other topics across the curriculum. appeared on the beach, too. None of these things The islands are Family Island, Tropical Island, Space were on the beach last week. Island, Movie Studio Island, Ice Island and Future Island. There is an online educational game for Then they meet Zack, a movie director who the students using Poptropica English, with an is making a pirate movie on the island. He is adventure on each Island. worried though, as he has lost the pirate captain’s costume. Max and Clara offer to help Zack find Movie Studio Island Adventure is written by Hawys Captain Crab’s costume. The mustache, beard, hat, Morgan, an author and editor specializing in and a boot are missing. primary and preschool ELT materials and CLIL. The children see a monkey wearing the pirate’s boot in the castle. -

Captain Plank's Pirate Adventure

Key Stage 1 – My Pirate Adventure Captain Plank’s Pirate Adventure Once there was a poor young pirate named Captain Plank. He lived with his parrot Nelson in a tiny, run-down red shack near the sea. On Monday, Captain Plank decided to head off in search of pirate treasure. But then he realised he didn’t look like a pirate. So he rummaged in his cupboard and found a big black hat. “Arrgh”, he said. “Now I feel more like a pirate.” On Tuesday, Captain Plank was nearly ready to start his adventure. But then he realised he had another problem. He didn’t have a ship. So he looked around the harbour and stole a speedy ship with three sails while no one was looking. He named his ship the Flying Dragon. Then he was ready to set sail! On Wednesday, Captain Plank pulled up the anchor, raised the sail and set out to sea. Nelson and the Captain were having a great time. They sailed so far out that they could not see land anymore. But then Captain Plank realised they were lost. So he ran into the ship’s cabin. [Insert picture of map] He searched high and low until he found a map to help them on their way. Then Captain Plank and Nelson weren’t so lost. On Thursday, Captain Plank wanted to scare other ships with his fearsome Jolly Roger flag. But he realised some sneaky pirates had climbed the mast and stolen it in the night. So he ran to the bow of the ship and found a new flag and some paint. -

TREASURE ISLAND ADVENTURES Globeducate Project Suitable for 4-5 Year Olds

TREASURE ISLAND ADVENTURES Globeducate Project Suitable for 4-5 year olds Globeducate Projects 2020 PROJECT TITLE - OVERVIEW ABOUT THE PROJECT PROJECT TASK You’ve been captured by Pirate Pointy Beard and find yourself upon the Jolly Roger ship with only Over the 10 sessions you will learn all there is to pirates and a parrot for company. know about being a pirate. Through a variety of creative and design activities, you’ll learn how to To survive you will need to learn how to act like a outwit the pirates and find the treasure so you pirate, walk like a pirate, talk like a pirate … BE a can get back home safely! pirate! Do it or face the plank! Are you up for the challenge, me hearties?! RESOURCES NOTES Recyclable materials such as cereal boxes, egg Some activities may require adult supervision. cartons, yoghurt pots, sponges, corks, markers, There is a video introduction for each session. scissors, glue, paints, paper, paintbrush, oil, Clicko n the image to access them. empty water bottle or jar. Click on links to listen to Pirate songs. See also cookery recipes. ©2020 Globeducate – Private and Confidential Treasure Island – A Pirate Adventure ScenarioYou find yourself aboard the Jolly Roger, the ship of the notoriously bad Pirate Pointy Beard. He likes to make his prisoners walk the plank! The only way to save yourself and get back home is to learn how to act, sing and dance like a pirate. You’ll discover how to make a treasure map, sink a ship and survive the dreaded scurvy! Don’t forget to have fun! Pirates aren’t all bad! Are you