Stevenson's Treasure Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson

Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson adapted for the stage by Stewart Skelton Stewart E. Skelton 6720 Franklin Place, #404 Copyright 1996 Hollywood, CA 90028 213.461.8189 [email protected] SETTING: AN ATTIC A PARLOR AN INN A WATERFRONT THE DECK OF A SHIP AN ISLAND A STOCKADE ON THE ISLAND CAST: VOICE OF BILLY BONES VOICE OF BLACK DOG VOICE OF MRS. HAWKINS VOICE OF CAP'N FLINT VOICE OF JIM HAWKINS VOICE OF PEW JIM HAWKINS PIRATES JOHNNY ARCHIE PEW BLACK DOG DR. LIVESEY SQUIRE TRELAWNEY LONG JOHN SILVER MORGAN SAILORS MATE CAPTAIN SMOLLETT DICK ISRAEL HANDS LOOKOUT BEN GUNN TIME: LATE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY TREASURE ISLAND/Skelton 1 SCENE ONE (A treasure chest sits alone on plank flooring. We hear the creak of rigging on a ship set adrift. As the lights begin to dim, we hear menacing, thrilling music building in the background. When a single spot is left illuminating the chest, the music comes to a crashing climax and quickly subsides to continue playing in the background. With the musical climax, the lid of the chest opens with a horrifying groan. Light starts to emanate from the chest, and the spotlight dims. Voices and the sounds of action begin to issue forth from the chest. The music continues underneath.) VOICE OF BILLY BONES (singing) "Fifteen men on the dead man's chest - Yo-ho-ho, and a bottle of rum! Drink and the devil had done for the rest - Yo-ho-ho, and a bottle of rum!" VOICE OF BLACK DOG Bill! Come, Bill, you know me; you know an old shipmate, Bill, surely. -

Ye Intruders Beware: Fantastical Pirates in the Golden Age of Illustration

YE INTRUDERS BEWARE: FANTASTICAL PIRATES IN THE GOLDEN AGE OF ILLUSTRATION Anne M. Loechle Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of the History of Art Indiana University November 2010 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee _________________________________ Chairperson, Sarah Burns, Ph.D. __________________________________ Janet Kennedy, Ph.D. __________________________________ Patrick McNaughton, Ph.D. __________________________________ Beverly Stoeltje, Ph.D. November 9, 2010 ii ©2010 Anne M. Loechle ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii Acknowledgments I am indebted to many people for the help and encouragement they have given me during the long duration of this project. From academic and financial to editorial and emotional, I was never lacking in support. I am truly thankful, not to mention lucky. Sarah Burns, my advisor and mentor, supported my ideas, cheered my successes, and patiently edited and helped me to revise my failures. I also owe her thanks for encouraging me to pursue an unorthodox topic. From the moment pirates came up during one of our meetings in the spring of 2005, I was hooked. She knew it, and she continuously suggested ways to expand the idea first into an independent study, and then into this dissertation. My dissertation committee – Janet Kennedy, Patrick McNaughton, and Beverly Stoeltje – likewise deserves my thanks for their mentoring and enthusiasm. Other scholars have graciously shared with me their knowledge and input along the way. David M. Lubin read a version of my third chapter and gave me helpful advice, opening up to me new ways of thinking about Howard Pyle in particular. -

Dt1962jwc.Pdf (13.95Mb)

. , A PLAN FOR EACilll;G TB3 IYOVEL TIZASURE ISiAND , I IN THE JUNIOR FiIGII SCHOOL %// ,.; A Field Report presented to The Graduate Division Drake University In Partial fulfill me^ of the Requirements for the Degree :!aster of Science in Education by John Yii1lia.m Crawford June 1962 A PLAN FOR TEACrIIIJG THE NOTEL T%AS'JRE ISLlLED IN THE JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL by John lfilliam Crawford Approved by Cormnittee : (I . & . ,I. ..% Dean of the Gradcat-a Division ' CFirnR PWY I . THE PROBLEi!. PROmDURES UaD. AiD JJSTIFICATIO!? OF THE STUDY e.................. 1 Statement of the problem ............. 1 Procedures used ................. 1 Justification of the study ............ 1 11. A CRITICAL M-XLYSIS OF TIF, NWL . 4 I11 . AIXTAILSD EACLiIIfG PWY: FOR !l?RUSUFi ISWD .... 20 Part I1 ..................... 25 Fad7 ...................... 33 part VI ..................... 35 THE PROBIEI~I, PROCEDURES USED, MJD JUSTIFICATION OF T-IE SmY Statement --of the problem. It was the purpose of this study to present a plan for teaching the novel Treasure Island in the junf or high school. Procedures -used. The plan of the study was threefold: (1) A survey of criticisms of Robert Louis Stevenson and his work Treasure Island was made by using books and periodicals; (2) teach- ing plana used suocessfully by other teachers for this novel were surveyed; and (3) audio-visual aids were sought which might b used in certain parts of the study. Justifioation --of the study. In the experience of the writer, to find a pieoe of literature that sustains the interest of boys and cirla of junior high age is a difficult task. -

Pirates and Perils of the Deep! Chatterbooks Activity Pack

Pirates and Perils of the Deep! Chatterbooks Activity Pack Pirates and Perils of the Deep! Reading and activity ideas for your Chatterbooks group About this pack Ahoy, me Hearties – and shiver me timbers! Here be a Chatterbooks pack full of swashbuckling pirate fun – activity ideas and challenges, and great reading for your group! The pack is brought to you by The Reading Agency and their publisher partnership Children’s Reading Partners Chatterbooks [ www.readinggroups.org/chatterbooks] is a reading group programme for children aged 4 to 14 years. It is coordinated by The Reading Agency and its patron is author Dame Jacqueline Wilson. Chatterbooks groups run in libraries and schools, supporting and inspiring children’s literacy development by encouraging them to have a really good time reading and talking about books. The Reading Agency is an independent charity working to inspire more people to read more through programmes for adults, young people and Children – including the Summer Reading Challenge, and Chatterbooks. See www.readingagency.org.uk Children’s Reading Partners is a national partnership of children’s publishers and libraries working together to bring reading promotions and author events to as many children and young people as possible. Contents 2 Things to talk about 2 Activity ideas 8 Chatterbooks double session plan, with a pirates theme 10 Pirates and perils quiz 11 Pirates and perils: great titles to read 17 More swashbuckling stories For help in planning your Chatterbooks meeting, have a look at these Top Tips for a Successful Session 2 Pirates and Perils of the Deep! Chatterbooks Activity Pack Ideas for your Chatterbooks sessions Things to talk about What do you know about pirates? Get together a collection of pirate books – stories and non-fiction – so you’ve got lots to refer to, and plenty of reading for your group to share. -

{PDF EPUB} Lost Cabin Fever by Bella Silver Lost: Cabin Fever by Bella Silver

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Lost Cabin Fever by Bella Silver Lost: Cabin Fever by Bella Silver. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 6615a880292dd6fd • Your IP : 116.202.236.252 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. What Happens to Your Body When You Spend So Much Time Inside? It’s possible to have too much of a good thing—even spending time in your own home. For many, the first few weeks of staying at home, lockdown, and social distancing were ideal. You had an excuse to cancel all your plans, wear sweatpants all day, and finally binge-watch the best shows on Netflix. But as weeks turned into months, for many of us, hanging out at home has lost its luster. Now you feel irritable, restless, and in a bad mood. Chances are, you’re not the only one who is feeling a little bummed out. Cabin fever isn’t an urban legend; it exists and can definitely rear its ugly head when you spend too much time indoors. -

Jemf Quarterly

JEMF QUARTERLY JOHN EDWARDS MEMORIAL FOUNDATION VOL. XII SPRING 1976 No. 41 THE JEMF The John Edwards Memorial Foundation is an archive and research center located in the Folklore and Mythology Center of the University of California at Los Angeles. It is chartered as an educational non-profit corporation, supported by gifts and contributions. The purpose of the JEMF is to further the serious study and public recognition of those forms of American folk music disseminated by commercial media such as print, sound recordings, films, radio, and television. These forms include the music referred to as cowboy, western, country & western, old time, hillbilly, bluegrass, mountain, country ,cajun, sacred, gospel, race, blues, rhythm' and blues, soul, and folk rock. The Foundation works toward this goal by: gathering and cataloguing phonograph records, sheet music, song books, photographs, biographical and discographical information, and scholarly works, as well as related artifacts; compiling, publishing, and distributing bibliographical, biographical, discographical, and historical data; reprinting, with permission, pertinent articles originally appearing in books and journals; and reissuing historically significant out-of-print sound recordings. The Friends of the JEMF was organized as a voluntary non-profit association to enable persons to support the Foundation's work. Membership in the Friends is $8.50 (or more) per calendar year; this fee qualifies as a tax deduction. Gifts and contributions to the Foundation qualify as tax deductions. DIRECTORS ADVISORS Eugene W. Earle, President Archie Green, 1st Vice President Ry Cooder Fred Hoeptner, 2nd Vice President David Crisp Ken Griffis, Secretary Harlan Dani'el D. K. Wilgus, Treasurer David Evans John Hammond Wayland D. -

TREASURE ISLAND the NOVEL and the MUSICAL 2 STUDY MATERIALS

Maine State Music Theatre Curtis Memorial Library, Topsham Public Library, and Patten Free Library present A STUDY GUIDE TO TREASURE ISLAND The NOVEL and the MUSICAL 2 STUDY MATERIALS TREASURE ISLAND: THE NOVEL Robert Louis Stevenson Page 3 Treasure Island in Literary History Page 5 Fun Facts About the Novel Page 6 Historical Context of the Novel Page 7 Adaptations of Treasure Island on Film and Stage Page 9 Treasure Island: Themes Page 10 Treasure Island: Synopsis of the Novel Page 11 Treasure Island: Characters in the Novel Page 13 Treasure Island: Glossary Page 15 TREASURE ISLAND A Musical Adventure: THE ROBIN & CLARK MUSICAL Artistic Statement Page 18 The Creators of the Musical Page 19 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Themes Page 20 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Synopsis & Songs Page 21 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Cast of Characters Page 24 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: World Premiere Page 26 Press Quotes Page 27 QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION Page 28 MSMT’s Treasure Island A Musical Adventure Page 29 3 TREASURE ISLAND: THE NOVEL ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, on November 13, 1850, to Thomas and Margaret Stevenson. Lighthouse design was his father's and his family's profession, so at age seventeen, he enrolled at Edinburgh University to study engineering, with the goal of following in the family business. Lighthouse design never appealed to Stevenson, though, and he began studying law instead. His spirit of adventure truly began to appear at this stage, and during his summer vacations he traveled to France to be around young writers and painters. -

Pirate's Cove Rulebook

A game of swashbuckling and daring ! For 3-5 players ages 8 and above 60-90 minutes egendary home of lore and plunder… hideaway of pirates and buccaneers… Pirate’s Cove haunts the hearts and minds of every young lad who yearns L for a life at sea. Starting with a modestly outfitted sloop salvaged from last winter’s storm, you set sail to Pirate’s Cove one early morning, your eyes filled with visions of treasure and fame, your lungs filled with the salty air of the High Seas. Components Inside the box of treasures lie: N 1 Board map representing the seas and surrounding islands near Pirate’s Cove N 7 Pirate ship miniatures (1 per player & 2 Legendary Pirate black ships) N 5 Pirate Ship Mats and Captain’s Wheels (1 each per player) N 5 Wooden Fame markers (1 per player) N 20 Strength markers (wooden rings – 4 in each player’s color) N 112 Illustrated cards: • 60 Treasure cards • 5 Legendary Pirate summary cards • 1 Royal Navy summary card • 42 Tavern cards (Tavern on the back) - 4 Parrot cards - 7 Mastercraft cards - 14 Combat cards (8 Battle and 6 Volley cards) - 8 Event cards - 9 Fame cards (5 x1, 3 x2, 1 x3) • 4 Blank cards (1 Legendary Pirate card, 1 Event card, 1 battle and 1 volley combat cards) N 44 Doubloons (24 worth 1 gold and 20 worth 5 gold) N Treasure chests (Brown wooden cubes) N 6 wooden dice N 1 Rules booklet N 1 Summary Card 1 Days of Wonder Online access number Treasure (located on back of Rules) Fame Doubloon Treasure Tavern card(s) PIRATES TREASURE TAVERN Event Fame Parrot Combat Mastercraft Blank card Doubloon 2 Setting up the Game Place the board map of Pirate’s Cove Each player chooses: in the center of the table. -

A History of the Personal Computer Index/11

A History of the Personal Computer 6100 CPU. See Intersil Index 6501 and 6502 microprocessor. See MOS Legend: Chap.#/Page# of Chap. 6502 BASIC. See Microsoft/Prog. Languages -- Numerals -- 7000 copier. See Xerox/Misc. 3 E-Z Pieces software, 13/20 8000 microprocessors. See 3-Plus-1 software. See Intel/Microprocessors Commodore 8010 “Star” Information 3Com Corporation, 12/15, System. See Xerox/Comp. 12/27, 16/17, 17/18, 17/20 8080 and 8086 BASIC. See 3M company, 17/5, 17/22 Microsoft/Prog. Languages 3P+S board. See Processor 8514/A standard, 20/6 Technology 9700 laser printing system. 4K BASIC. See Microsoft/Prog. See Xerox/Misc. Languages 16032 and 32032 micro/p. See 4th Dimension. See ACI National Semiconductor 8/16 magazine, 18/5 65802 and 65816 micro/p. See 8/16-Central, 18/5 Western Design Center 8K BASIC. See Microsoft/Prog. 68000 series of micro/p. See Languages Motorola 20SC hard drive. See Apple 80000 series of micro/p. See Computer/Accessories Intel/Microprocessors 64 computer. See Commodore 88000 micro/p. See Motorola 80 Microcomputing magazine, 18/4 --A-- 80-103A modem. See Hayes A Programming lang. See APL 86-DOS. See Seattle Computer A+ magazine, 18/5 128EX/2 computer. See Video A.P.P.L.E. (Apple Pugetsound Technology Program Library Exchange) 386i personal computer. See user group, 18/4, 19/17 Sun Microsystems Call-A.P.P.L.E. magazine, 432 microprocessor. See 18/4 Intel/Microprocessors A2-Central newsletter, 18/5 603/4 Electronic Multiplier. Abacus magazine, 18/8 See IBM/Computer (mainframe) ABC (Atanasoff-Berry 660 computer. -

Finding List

I LUINO I S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Brittle Books Project, 2011. COPYRIGHT NOTIFICATION In Public Domain. Published prior to 1923. This digital copy was made from the printed version held by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. It was made in compliance with copyright law. Prepared for the Brittle Books Project, Main Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign by Northern Micrographics Brookhaven Bindery La Crosse, Wisconsin 2011 1ol - 1a ; M f FINDING LIST OF THE FREE PUBLIC LIBRARY MACOMB, ILLINOIS. PRICE 10 CENTS. FINDING LIST -OF THE- SPULBLIICI RARY9 MACOMB, ILLINOIS. Organized Novenber 22, 1881. Opened To Public April 8, 1882. BOARD OF DIRECTORS 1897T. President, Mr. Chas. W. Flack. Secretary, Mr. P. E. Kiting. qrs. W. S. Bailey. Mrs. A. Blount. Mrs. J. M. K'ee-fe er. Tjt[r. A. McLean. Mr. A. K. Lodge. Mr. W. H. Bloll lv Mr. L. F. Gumbart. Librarian, Miss Mahala Phelps. MACOMB, ILLINOIS: THE EAGLE PRINTING COMPANY. 1897. 2 FREE PUBLIC LIBRARY. FIules a9d eu1a io9rs. As Revised at Regular Meeting of the Board of Directors March 29, 1897. 1st. The officers of said Board of Direct- which shall at all times be open to the in- ors shall consist of a President, Vice-Presi- spection of any member of the board. He dent, Secretary, Treasurer, and such other shall report to the board once every month officers as may be founid necessary from the receipts and expenditures of the library time to time hereafter, all of whom shall be and other matters regarding the progress elected by ballot, unless directed otherwise or wants of the same. -

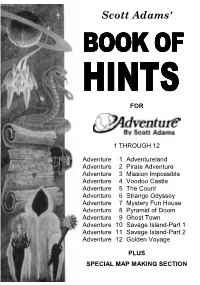

Scott Adams' BOOK of HINTS FOR

Scott Adams' BOOK OF HINTS FOR 1 THROUGH 12 Adventure 1 Adventureland Adventure 2 Pirate Adventure Adventure 3 Mission Impossible Adventure 4 Voodoo Castle Adventure 5 The Count Adventure 6 Strange Odyssey Adventure 7 Mystery Fun House Adventure 8 Pyramid of Doom Adventure 9 Ghost Town Adventure 10 Savage Island-Part 1 Adventure 11 Savage Island-Part 2 Adventure 12 Golden Voyage PLUS SPECIAL MAP MAKING SECTION THE FOLLOWING IS A METHOD USEFUL IN MAPPING ADVENTURES Each room is represented by a box with the name of the room in it, and all original items found in it noted alongside. FOREST Directions from a location are indicated by a line coming out of anywhere on the box, but with the direction leaving the box indicated by the first letter of that direction. GROVE GROVE The above shows it is East from the grove to the swamp and West from the swamp to the grove. In the case of being able to go only in one direction, an arrow is put at the end of the path. FOREST GROVE GROVE This indicates that upon leaving the grove you go north to the forest, but that you cannot return! The best way to use this system is that, upon entering a location, you draw a line representing each possible exit and its location. Later you connect them to rooms as you continue your exploration. FOREST MEADOW GROVE GROVE The advantage is that you will not forget to explore an exit once you get past your initial probe. Another advantage of this system is that you never need redraw your map as you stick extra locations anywhere on your paper. -

Part Six ~ Captain Silver Chapter 28: in the Enemy’S Camp

Treasure Island Part Six ~ Captain Silver CHAPTER 28: IN THE ENEMY’S CAMP The red glare of the torch, lighting up the interior of the block house, showed me the worst of my apprehensions realized. The pirates were in possession of the house and stores: there was the cask of cognac, there were the pork and bread, as before, and what tenfold increased my hor- ror, not a sign of any prisoner. I could only judge that all had perished, and my heart smote me sorely that I had not been there to perish with them. There were six of the buccaneers, all told; not another man was left alive. Five of them were on their feet, flushed and swollen, suddenly called out of the first sleep of drunkenness. The sixth had only risen upon his elbow; he was deadly pale, and the blood-stained bandage round his head told that he had recently been wounded, and still more recently dressed. I remembered the man who had been shot and had run back among the woods in the great attack, and doubted not that this was he. The parrot sat, preening her plumage, on Long John’s shoulder. He himself, I thought, looked somewhat paler and more stern than I was used to. He still wore the fine broadcloth suit in which he had fulfilled his mission, but it was bitterly the worse for wear, daubed with clay and torn with the sharp briers of the wood. “So,” said he, “here’s Jim Hawkins, shiver my timbers! Dropped in, like, eh? Well, come, I take that friendly.” And thereupon he sat down across the brandy cask and began to fill a pipe.