Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Source Projects As Incubators of Innovation

RESEARCH CONTRIBUTIONS TO ORGANIZATIONAL SOCIOLOGY AND INNOVATION STUDIES / STUTTGARTER BEITRÄGE ZUR ORGANISATIONS- UND INNOVATIONSSOZIOLOGIE SOI Discussion Paper 2017-03 Open Source Projects as Incubators of Innovation From Niche Phenomenon to Integral Part of the Software Industry Jan-Felix Schrape Institute for Social Sciences Organizational Sociology and Innovation Studies Jan-Felix Schrape Open Source Projects as Incubators of Innovation. From Niche Phenomenon to Integral Part of the Software Industry. SOI Discussion Paper 2017-03 University of Stuttgart Institute for Social Sciences Department of Organizational Sociology and Innovation Studies Seidenstr. 36 D-70174 Stuttgart Editor Prof. Dr. Ulrich Dolata Tel.: +49 711 / 685-81001 [email protected] Managing Editor Dr. Jan-Felix Schrape Tel.: +49 711 / 685-81004 [email protected] Research Contributions to Organizational Sociology and Innovation Studies Discussion Paper 2017-03 (May 2017) ISSN 2191-4990 © 2017 by the author(s) Jan-Felix Schrape is senior researcher at the Department of Organizational Sociology and Innovation Studies, University of Stuttgart (Germany). [email protected] Additional downloads from the Department of Organizational Sociology and Innovation Studies at the Institute for Social Sciences (University of Stuttgart) are filed under: http://www.uni-stuttgart.de/soz/oi/publikationen/ Abstract Over the last 20 years, open source development has become an integral part of the software industry and a key component of the innovation strategies of all major IT providers. Against this backdrop, this paper seeks to develop a systematic overview of open source communities and their socio-economic contexts. I begin with a recon- struction of the genesis of open source software projects and their changing relation- ships to established IT companies. -

Alevist Vallamajani from Borough to Community House

Eesti Vabaõhumuuseumi Toimetised 2 Alevist vallamajani Artikleid maaehitistest ja -kultuurist From borough to community house Articles on rural architecture and culture Tallinn 2010 Raamatu väljaandmist on toetanud Eesti Kultuurkapital. Toimetanud/ Edited by: Heiki Pärdi, Elo Lutsepp, Maris Jõks Tõlge inglise keelde/ English translation: Tiina Mällo Kujundus ja makett/ Graphic design: Irina Tammis Trükitud/ Printed by: AS Aktaprint ISBN 978-9985-9819-3-1 ISSN-L 1736-8979 ISSN 1736-8979 Sisukord / Contents Eessõna 7 Foreword 9 Hanno Talving Hanno Talving Ülevaade Eesti vallamajadest 11 Survey of Estonian community houses 45 Heiki Pärdi Heiki Pärdi Maa ja linna vahepeal I 51 Between country and town I 80 Marju Kõivupuu Marju Kõivupuu Omad ja võõrad koduaias 83 Indigenous and alien in home garden 113 Elvi Nassar Elvi Nassar Setu küla kontrolljoone taga – Lõkova Lykova – Setu village behind the 115 control line 149 Elo Lutsepp Elo Lutsepp Asustuse kujunemine ja Evolution of settlement and persisting ehitustraditsioonide püsimine building traditions in Peipsiääre Peipsiääre vallas. Varnja küla 153 commune. Varnja village 179 Kadi Karine Kadi Karine Miljööväärtuslike Virumaa Milieu-valuable costal villages of rannakülade Eisma ja Andi väärtuste Virumaa – Eisma and Andi: definition määratlemine ja kaitse 183 of values and protection 194 Joosep Metslang Joosep Metslang Palkarhitektuuri taastamisest 2008. Methods for the preservation of log aasta uuringute põhjal 197 architecture based on the studies of 2008 222 7 Eessõna Eesti Vabaõhumuuseumi toimetiste teine köide sisaldab 2008. aasta teaduspäeva ettekannete põhjal kirjutatud üpris eriilmelisi kirjutisi. Omavahel ühendab neid ainult kaks põhiteemat: • maaehitised ja maakultuur. Hanno Talvingu artikkel annab rohkele arhiivimaterjalile ja välitööaine- sele toetuva esmase ülevaate meie valdade ja vallamajade kujunemisest alates 1860. -

Estonian Academy of Sciences Yearbook 2014 XX

Facta non solum verba ESTONIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES YEAR BOOK ANNALES ACADEMIAE SCIENTIARUM ESTONICAE XX (47) 2014 TALLINN 2015 ESTONIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES The Year Book was compiled by: Margus Lopp (editor-in-chief) Galina Varlamova Ülle Rebo, Ants Pihlak (translators) ISSN 1406-1503 © EESTI TEADUSTE AKADEEMIA CONTENTS Foreword . 5 Chronicle . 7 Membership of the Academy . 13 General Assembly, Board, Divisions, Councils, Committees . 17 Academy Events . 42 Popularisation of Science . 48 Academy Medals, Awards . 53 Publications of the Academy . 57 International Scientific Relations . 58 National Awards to Members of the Academy . 63 Anniversaries . 65 Members of the Academy . 94 Estonian Academy Publishers . 107 Under and Tuglas Literature Centre of the Estonian Academy of Sciences . 111 Institute for Advanced Study at the Estonian Academy of Sciences . 120 Financial Activities . 122 Associated Institutions . 123 Associated Organisations . 153 In memoriam . 200 Appendix 1 Estonian Contact Points for International Science Organisations . 202 Appendix 2 Cooperation Agreements with Partner Organisations . 205 Directory . 206 3 FOREWORD The Estonian science and the Academy of Sciences have experienced hard times and bearable times. During about the quarter of the century that has elapsed after regaining independence, our scientific landscape has changed radically. The lion’s share of research work is integrated with providing university education. The targets for the following seven years were defined at the very start of the year, in the document adopted by Riigikogu (Parliament) on January 22, 2014 and entitled “Estonian research and development and innovation strategy 2014- 2020. Knowledge-based Estonia”. It starts with the acknowledgement familiar to all of us that the number and complexity of challenges faced by the society is ever increasing. -

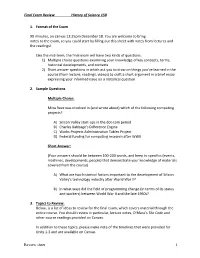

Final Exam Review History of Science 150

Final Exam Review History of Science 150 1. Format of the Exam 90 minutes, on canvas 12:25pm December 18. You are welcome to bring notes to the exam, so you could start by filling out this sheet with notes from lectures and the readings! Like the mid-term, the final exam will have two kinds of questions. 1) Multiple choice questions examining your knowledge of key concepts, terms, historical developments, and contexts 2) Short answer questions in which ask you to draw on things you’ve learned in the course (from lecture, readings, videos) to craft a short argument in a brief essay expressing your informed issue on a historical question 2. Sample Questions Multiple Choice: Mina Rees was involved in (and wrote about) which of the following computing projects? A) Silicon Valley start-ups in the dot-com period B) Charles Babbage’s Difference Engine C) Works Projects Administration Tables Project D) Federal funding for computing research after WWII Short Answer: (Your answers should be between 100-200 words, and keep to specifics (events, machines, developments, people) that demonstrate your knowledge of materials covered from the course) A) What are two historical factors important to the development of Silicon Valley’s technology industry after World War II? B) In what ways did the field of programming change (in terms of its status and workers) between World War II and the late 1960s? 3. Topics to Review: Below, is a list of ideas to review for the final exam, which covers material through the entire course. You should review in particular, lecture notes, O’Mara’s The Code and other course readings provided on Canvas. -

Download This PDF File

SOCIETY. INTEGRATION. EDUCATION Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference. Volume V, May 22th -23th, 2020. 795-807 THE DEVELOPMENT OF TOWN-SHIELDS’ PLANNING IN BISHOPRICS OF LIVONIA DURING THE 13TH–14TH CENTURIES Silvija Ozola Riga Technical University, Latvia Abstract. Traditions of the Christianity centres’ formation can be found in Jerusalem’s oldest part where instead of domestic inhabitants’ dwellings the second king of Israel (around 1005 BC–965 BC) David built his residence on a top of the Temple Mount surrounded by deep valleys. His fortress – the City of David protected from the north side by inhabitants’ stone buildings on a slope was an unassailable public and spiritual centre that northwards extended up to the Ophel used for the governance. David’s son, king of Israel (around 970–931 BC) Solomon extended the fortified urban area where Templum Solomonis was built. In Livonia, Bishop Albrecht obtained spacious areas, where he established bishoprics and towns. At foothills, residential building of inhabitants like shields guarded Bishop’s residence. The town- shield was the Dorpat Bishopric’s centre Dorpat and the Ösel–Wiek Bishopric’s centre Haapsalu. The town of Hasenpoth in the Bishopric of Courland (1234–1583) was established at subjugated lands inhabited by the Cours: each of bishopric's urban structures intended to Bishop and the Canonical Chapter was placed separately in their own village. The main subject of research: the town-shields’ planning in Livonia. Research problem: the development of town-shields’ planning at bishoprics in Livonia during the 13th and 14th century have been studied insufficiently. Historians in Latvia often do not take into account studies of urban planning specialists on historical urban planning. -

Song Traditions of the Volga-Ural Tatars in the 21St Century: Issues in the Transmission of Historic Singing Styles Nailya Almeeva

Song Traditions of the Volga-Ural Tatars in the 21st Century: Issues in the Transmission of Historic Singing Styles Nailya Almeeva In the 20th century ethnic music attracted this has long been a phenomenon of revival great interest. With increasing ease of travel performance of folklore in live performance, not and communication, countries and continents by the bearers of folklore musical thinking and seemed to become closer, and access to original hearing but, loosely speaking, by those who folk material became ever easier. Ethnic music learned it. Understanding the value of the original could now be found not only in print but in live sound of ritual (time-bound) singing, one cannot performance, on television and on the internet. remain indiff erent to its revival, particularly once As a result, the whole spectrum of methods and one is aware of what can be lost during such types of intoning (a term introduced by Izaly revival. Zemtsovsky (1981: 87), which means types of voice Globalisation and the mass media have had a production) and sounding techniques of the oral particularly negative eff ect on ritual (time-bound) tradition could be experienced, even without genres and on the types of folklore dependent leaving home. Many of the methods bear the on a traditional way of life, on pre-industrial ways characteristics common for earlier, sometimes of production and on the natural environment. very ancient, historic epochs. In those places where these have ceased, ritual Traditional societies became urbanised, and folklore fades and eventually disappears. the all-permeating eff ects of the mass media The issues described above apply to the ritual overwhelmed the traditional ear. -

Estonian Yiddish and Its Contacts with Coterritorial Languages

DISSERT ATIONES LINGUISTICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 1 ESTONIAN YIDDISH AND ITS CONTACTS WITH COTERRITORIAL LANGUAGES ANNA VERSCHIK TARTU 2000 DISSERTATIONES LINGUISTICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS DISSERTATIONES LINGUISTICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 1 ESTONIAN YIDDISH AND ITS CONTACTS WITH COTERRITORIAL LANGUAGES Eesti jidiš ja selle kontaktid Eestis kõneldavate keeltega ANNA VERSCHIK TARTU UNIVERSITY PRESS Department of Estonian and Finno-Ugric Linguistics, Faculty of Philosophy, University o f Tartu, Tartu, Estonia Dissertation is accepted for the commencement of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in general linguistics) on December 22, 1999 by the Doctoral Committee of the Department of Estonian and Finno-Ugric Linguistics, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Tartu Supervisor: Prof. Tapani Harviainen (University of Helsinki) Opponents: Professor Neil Jacobs, Ohio State University, USA Dr. Kristiina Ross, assistant director for research, Institute of the Estonian Language, Tallinn Commencement: March 14, 2000 © Anna Verschik, 2000 Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastuse trükikoda Tiigi 78, Tartu 50410 Tellimus nr. 53 ...Yes, Ashkenazi Jews can live without Yiddish but I fail to see what the benefits thereof might be. (May God preserve us from having to live without all the things we could live without). J. Fishman (1985a: 216) [In Estland] gibt es heutzutage unter den Germanisten keinen Forscher, der sich ernst für das Jiddische interesiere, so daß die lokale jiddische Mundart vielleicht verschwinden wird, ohne daß man sie für die Wissen schaftfixiert -

Les Cahiers Du CIÉRA

C novembre 2014 Les Cahiers du CIÉRA A n°12 H I Les Cahiers du CIÉRA Women and Leadership: Reflections of a Northwest Territories Inuit Woman Helen Kitekudlak E R Inuit Women Educational Leaders in Nunavut S Fiona Walton, Darlene O’Leary, Naullaq Arnaquq, Nunia Qanatsiaq-Anoee To Inspire and be Inspired by Inuit Women in Leadership du Lucy Aqpik C (Re)trouver l’équilibre en habitant en ville : le cas de jeunes Inuit à Ottawa I Stéphanie Vaudry É Souvenirs de Lioudmila Aïnana, une aînée yupik R Entretien réalisé par Dmitryi Oparin A Sápmelaš, être Sámi. Portraits et réflexions de femmes sámi Annabelle Fouquet Présentation d’œuvres de l’artiste Eruoma Awashish Sahara Nahka Bertrand La violence envers les femmes autochtones : une question de droits de la per- sonne Renée Dupuis Concordances et concurrences entre droit à l’autonomie des peuples autoch- tones et droits individuels : l’exemple du droit des femmes autochtones d’ap- partenir à une nation sans discrimination 2 Le leadership des femmes inuit et des Premières nations : Geneviève Motard 0 Trajectoires et obstacles 1 Leadership and Governance CURA in Nunavut and Nunavik 4 * ISSN 1919-6474 12 Les Cahiers du CIÉRA Les Cahiers du CIÉRA Les Cahiers du CIÉRA publient les actes de colloques, de journées d’étude et de séminaires organisés par les chercheurs du CIÉRA, ainsi que leurs projets d’ouvrages collectifs et des contributions ponctuelles. La publication des Cahiers du CIÉRA est également ouverte aux membres des Premières nations, aux Inuit et aux Métis, ainsi qu’à tous les chercheurs intéressés aux questions autochtones. -

IBEF Presentataion

WEST BENGAL CULTURALLY ARTISTIC For updated information, please visit www.ibef.org July 2017 Table of Content Executive Summary .…………….….……...3 Advantage State ...………………………….4 Vision 2022 …………..……..…………..…..5 West Bengal – An Introduction …….……....6 Annual Budget 2015-16 ……………………18 Infrastructure Status ..................................19 Business Opportunities ……..…………......42 Doing Business in West Bengal …...……...63 State Acts & Policies ….….………..............68 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY One of the largest state . West Bengal, India’s 6th largest economy, had a gross state domestic product (GSDP) of US$ 140.56 billion economies in 2016-17. The state’s GSDP grew at a CAGR of 10.42% during 2005-16. Kolkata as the next IT . By 2015-16, 8 IT parks located at Barjora, Rajarhat, Asansol, Durgapur Phase II, Bolpur, Siliguri Phase II, Puralia & Kharagpur started operating. Establishment of 7 new IT parks at Haldia, Krishnanagar, Kalyani, hub Bantala, Taratala, Howrah, Malda is expected to start soon in next 5 years. Major producer of . In 2016-17, West Bengal was the 2nd largest producer of potato in India, accounting for about 25.06% of the potato country’s potato output. The state’s potato production stood at 11 million tonnes in 2016-17. West Bengal is the largest producer of rice in India. In 2016-17, rice production in West Bengal totalled to Largest rice producer 16.2 million tonnes, which is expected to cross 17 million tonnes by 2017. West Bengal is the 3rd largest state in India in term of mineral production, accounting for about one-fifth of Coal rich state total mineral production. Coal accounts for 99% of extracted minerals. Source: Statistics of West Bengal, Government of West Bengal 3 WEST BENGAL For updated information, please visit www.ibef.org ADVANTAGE: WEST BENGAL 2014-15 Geographic and cost advantage Rich labour pool 2022-23 T . -

Ethnic Problems of the Baltic Region Этническая Проблематика

Lebedev, S.V. (2021). Ethnic problems of the Baltic region . Ethnic problems of the era of globalization. Collection of Scientific Articles, European Scientific e-Journal, 03-2021 (09), 39-55. Hlučín-Bobrovníky: “Anisiia Tomanek” OSVČ. DOI: 10.47451/ eth2021-01-002 EOI: 10.11244/eth2021 -01-002 Лебедев, С.В. (2021). Этническая проблематика Прибалтийского региона. Ethnic problems of the era of globalization. Collection of Scientific Articles, European Scientific e-Journal, 03-2021 (09), 39-55. European Scientific e- Journal. Hlučín-Bobrovníky: “Anisiia Tomanek” OSVČ. Sergey V. Lebedev Full Professor, Doctor of Philosophical Sciences Head of the Department of Philosophy Higher School of Folk Arts (Academy) St Petersburg, Russia ORCID: 0000-0002-7994-2660 E-mail: [email protected] Ethnic problems of the Baltic region Abstract: The research is devoted to the ethnic problems of the Baltic region (the territory of 3 former Soviet republics – Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania). This topic remains relevant, despite the fact that these republics do not have a special global political, economic and cultural influence. The region has almost lost its industrial potential. In the Baltic States, the population is rapidly declining, returning to the figures of more than a century ago. The research shows the reasons why civil society has not developed in the Baltic States. The result is the fragmentation of society. The basis of the research is based on the historical method. Although there is a fairly significant scientific literature on the history of the region, mainly in Russian, this topic is usually reduced to the history of aboriginal peoples, which cannot be considered historically correct. -

Fifth Periodical Report Presented to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe in Accordance with Article 15 of the Charter

Strasbourg, 17 November 2017 MIN-LANG (2017) PR 7 EUROPEAN CHARTER FOR REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES Fifth periodical report presented to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe in accordance with Article 15 of the Charter FINLAND THE FIFTH PERIODIC REPORT BY THE GOVERNMENT OF FINLAND ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE EUROPEAN CHARTER FOR REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES NOVEMBER 2017 2 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................................................6 PART I .................................................................................................................................................................7 1. BASIC INFORMATION ON FINNISH POPULATION AND LANGUAGES....................................................................7 1.1. Finnish population according to mother tongue..........................................................................................7 1.2. Administration of population data ..............................................................................................................9 2. SPECIAL STATUS OF THE ÅLAND ISLANDS.............................................................................................................9 3. NUMBER OF SPEAKERS OF REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES IN FINLAND.................................................10 3.1. The numbers of persons speaking a regional or minority language..........................................................10 3.2. Swedish ......................................................................................................................................................10 -

Abstracts English

International Symposium: Interaction of Turkic Languages and Cultures Abstracts Saule Tazhibayeva & Nevskaya Irina Turkish Diaspora of Kazakhstan: Language Peculiarities Kazakhstan is a multiethnic and multi-religious state, where live more than 126 representatives of different ethnic groups (Sulejmenova E., Shajmerdenova N., Akanova D. 2007). One-third of the population is Turkic ethnic groups speaking 25 Turkic languages and presenting a unique model of the Turkic world (www.stat.gov.kz, Nevsakya, Tazhibayeva, 2014). One of the most numerous groups are Turks deported from Georgia to Kazakhstan in 1944. The analysis of the language, culture and history of the modern Turkic peoples, including sub-ethnic groups of the Turkish diaspora up to the present time has been carried out inconsistently. Kazakh researchers studied history (Toqtabay, 2006), ethno-political processes (Galiyeva, 2010), ethnic and cultural development of Turkish diaspora in Kazakhstan (Ibrashaeva, 2010). Foreign researchers devoted their studies to ethnic peculiarities of Kazakhstan (see Bhavna Dave, 2007). Peculiar features of Akhiska Turks living in the US are presented in the article of Omer Avci (www.nova.edu./ssss/QR/QR17/avci/PDF). Features of the language and culture of the Turkish Diaspora in Kazakhstan were not subjected to special investigation. There have been no studies of the features of the Turkish language, with its sub- ethnic dialects, documentation of a corpus of endangered variants of Turkish language. The data of the pre-sociological surveys show that the Kazakh Turks self-identify themselves as Turks Akhiska, Turks Hemshilli, Turks Laz, Turks Terekeme. Unable to return to their home country to Georgia Akhiska, Hemshilli, Laz Turks, Terekeme were scattered in many countries.