The Ethical Record Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

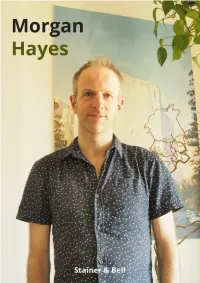

Morgan Hayes, Including a Performance Diary and News of Recent Works, May Be Found At

Stainer & Bell CONTENTS Biographical Note .............................................................2 Music for Orchestra ..........................................................5 Music for String Orchestra ................................................6 Ensemble Works ...............................................................6 Works for Solo Instrument and Ensemble .......................10 Works for Flexible Instrumentation .................................11 Instrumental Chamber Music .........................................12 Works for Solo Piano .......................................................14 Choral Works ..................................................................16 Vocal Chamber Music .....................................................16 Works for Solo Voice .......................................................17 Discography....................................................................17 Alphabetical List of Works...............................................19 Ordering Information ......................................................20 Further information about the music of Morgan Hayes, including a performance diary and news of recent works, may be found at www.stainer.co.uk/hayes.html Cover design: Joe Lau August 2019 1 Morgan Hayes Born in 1973, Morgan Hayes reflects the cultural pluralism of his generation in his open and relaxed attitude to many kinds of musical expression. At the same time, he has pursued a single-minded artistic vision that has won him admirers from among the ranks -

Programme Artikulationen 2017

Programme ARTikulationen 2017 Introduction 2 Research Festival Programme 4 Thursday, 5 October 2017 6 Friday, 6 October 2017 29 Saturday, 7 October 2017 43 Further Doctoral Researchers (Dr. artium), Internal Supervisors and External Advisors 51 Artistic Doctoral School: Team 68 Venues and Public Transport 69 Credits 70 Contact and Partners 71 1 Introduction ARTikulationen. A Festival of Artistic Research (Graz, 5–7 October 2017) Artistic research is currently a much-talked about and highly innovative field of know- ledge creation which combines artistic with academic practice. One of its central features is ambitious artistic experiments exploring musical and other questions, systematically bringing them into dialogue with reflection, analysis and other academic approaches. ARTikulationen, a two-and-a-half day festival of artistic research that has been running under that name since 2016, organised by the Artistic Doctoral School (KWDS) of the Uni- versity of Music and Performing Arts Graz (KUG), expands the pioneering format deve- loped by Ulf Bästlein and Wolfgang Hattinger in 2010, in which the particular moment of artistic research – namely audible results, which come about through a dynamic between art and scholarship that is rooted in methodology – becomes something the audience can understand and experience. In Alfred Brendel, Georg Friedrich Haas and George Lewis, the festival brings three world- famous and influential personalities and thinkers from the world of music to Graz as key- note speakers. George Lewis will combine his lecture with a version of his piece for soloist and interactive grand piano. The presentations at ARTikulationen encompass many different formats such as keynotes, lecture recitals, guest talks, poster presentations and a round table on practices in artistic research. -

Rediscover Northern Ireland Report Philip Hammond Creative Director

REDISCOVER NORTHERN IRELAND REPORT PHILIP HAMMOND CREATIVE DIRECTOR CHAPTER I Introduction and Quotations 3 – 9 CHAPTER II Backgrounds and Contexts 10 – 36 The appointment of the Creative Director Programme and timetable of Rediscover Northern Ireland Rationale for the content and timescale The budget The role of the Creative Director in Washington DC The Washington Experience from the Creative Director’s viewpoint. The challenges in Washington The Northern Ireland Bureau Publicity in Washington for Rediscover Northern Ireland Rediscover Northern Ireland Website Audiences at Rediscover Northern Ireland Events Conclusion – Strengths/Weaknesses/Potential Legacies CHAPTER III Artist Statistics 37 – 41 CHAPTER IV Event Statistics 42 – 45 CHAPTER V Chronological Collection of Reports 2005 – 07 46 – 140 November 05 December 05 February 06 March 07 July 06 September 06 January 07 CHAPTER VI Podcasts 141 – 166 16th March 2007 31st March 2007 14th April 2007 1st May 2007 7th May 2007 26th May 2007 7th June 2007 16th June 2007 28th June 2007 1 CHAPTER VII RNI Event Analyses 167 - 425 Community Mural Anacostia 170 Community Poetry and Photography Anacostia 177 Arts Critics Exchange Programme 194 Brian Irvine Ensemble 221 Brian Irvine Residency in SAIL 233 Cahoots NI Residency at Edge Fest 243 Healthcare Project 252 Camerata Ireland 258 Comic Book Artist Residency in SAIL 264 Comtemporary Popular Music Series 269 Craft Exhibition 273 Drama Residency at Catholic University 278 Drama Production: Scenes from the Big Picture 282 Film at American Film -

THE MUSIC DREAMLAND QUARTET (1997, Revised in 2006)

Music by Fozié Majd (b.1938) and Amir Mahyar Tafreshipour (b.1974) Dreamland (for string quartet) (Majd) 20:57 1 I. Lento 6:10 2 II Delicamente e cantado 14:46 3 Pendar (for solo violin) (Tafreshipour) 6:44 4 Broken Times (for string quartet) (Tafreshipour) 9:38 Farãghi (In Absentia) (for violin and cello) (Majd) 21:10 5 I Mesto, molto lento 14:10 6 II Animato, ma non troppo allegro, relentlessy 6:59 Total playing time: 58:29 Darragh Morgan, violin (all tracks) Patrick Savage, violin (tracks 1-2, 4) Fiona Winning, viola (tracks 1-2, 4) Deidre Cooper, cello (tracks 1-2, 4-6) THE MUSIC DREAMLAND QUARTET (1997, revised in 2006) Dreamland is in two movements; the first acting as a lento introduction to the second movement which is designated as “Delicatamente e cantando,” – delicate with a singing lilt. The opening theme of the second movement is a predominant cyclic or ever-returning factor, assuming various transformations, also present in the finale “lento espressivo” section, as an undercurrent to the expressive romantic melody of the first violin. The thematic materials often evoke a certain mood or feeling associated with the Iranian Dastgah music, and include the use of microtones. In the title “Dreamland,” dream is meant to be understood as “maya” or illusion. Dreamland had its premiere in New York in May 2008, performed by members of the Bãrbad Chamber Orchestra, with Cyrus Beroukhim as its first violin, and Rãmin Heydarbeygi as its music director. Majd PENDAR for violin (2017) Pendar is a series of compositions for solo instruments. -

St John's Smith Square

ST JOHN’S SMITH SQUARE 2015/16 SEASON Discover a musical landmark Patron HRH The Duchess of Cornwall 2015/16 SEASON CONTENTS WELCOME TO ST JOHN’S SMITH SQUARE —— —— 01 Welcome 102 School concerts Whether you’re already a friend, or As renovation begins at Southbank 02 Season Overview 105 Discover more discovering us for the first time, I trust Centre, we welcome residencies from the 02 Orchestral Performance 106 St John’s history you’ll enjoy a rewarding and stimulating Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment 03 Choral & Vocal Music 108 Join us experience combining inspirational and London Sinfonietta, world-class 03 Opera 109 Subscription packages music, delicious food and good company performers from their International Piano 04 Period Instruments 110 Booking information in the fabulous grandeur of this historic Series and International Chamber Music 05 Regular Series 111 How to find us building – the UK’s only baroque Series, and a mid-summer performance 06 New Music 112 Footstool Restaurant concert venue. from the Philharmonia Orchestra. 07 Young Artists’ Scheme This is our first annual season brochure We’re proud of our reputation for quality 08 Festivals – a season that features more than 250 and friendly service, and welcome the 09 Southbank Centre concerts, numerous world premieres and thoughts of our visitors. So, if you have 10 Listings countless talented musicians. We’re also any comments, please let me know and discussing further exciting projects, so I’ll gladly discuss them with you. please keep an eye on our What’s On I look forward to welcoming you to guides or sign up to our e-newsletter. -

Andthe Anarchists Other Issues of "Anarchy"L Gontents of Il0

AilARCHYJ{0.109 3shillings lSpence 40cents "-*"*"'"'r ,Eh$ Russell andthe Anarchists Other issues of "Anarchy"l Gontents of il0. 109 Please note that the following issues are out of print: I to 15 inclusive, 26,27, 38, ANiARCHY 109 (Vol l0 No 3) MARCH 1970 65 March 1970 39, 66, 89, 90, 96, 98, 102. Vol. I 1961l. 1. Sex-and-Violence; 2. Workers' control; 3. What does anar- chism mcarr today?: 4. Deinstitutioni- sariorr; 5. Spain; 6. Cinema; 7. Adventure playgrourrd; 3. Anthropology; 9. Prison; 10. [ndustrial decentralisation. Neither God nor Master V. Ncill; 12. Who are the anarchists?; 13. Richard Drinnon 65 Direct action; 14. Disobcdience; 15. David Wills; 16. Ethics of anarchism; 17. Lum- lleilther God pcn proletariat ; I {l.Comprehensive schools; Russell and the anarchists 19. 'Ihcatrc; 20. Non-violence; 21. Secon- dary Vivian Harper 68 modern; 22. Marx and Bakunin. nor Master Vol. 3. l96f : 23. Squatters; 24. Com- murrity of scholars; 25. Cybernetics; 26. RIOHABD DNIililOI{ Counter-culture 'l'horcarri 27. Yor-rth; 28. Future of anar- chisml 2t). Spies for peace;30. Com- Kingsley lAidmer 18 rnurrity workshop; 31. Self-organising systcmsi 32. Orimc; 33. Alex Comfort; Kropotkin and his memoirs J4. Scicnce fiction. Nicolas Walter 84 .17. I won't votc; 38. Nottingham; 39. Tsoucn ITS Roors ARE DBEpLy BURIED, modern anarchism I Iorncr l-ancl 40. Unions; 41. Land; dates from the entry of the Bakuninists into the First Inter- 42. India; 43. Parents and teachers; 44, Observations on eNanttnv 104 l'rarrsport; 45. Thc Greeks;46. Anarchisrn national just a hundred years ago. -

Full Text (PDF)

Catalogue ISEA2009 15th International Symposium on Electronic Art 23 August – 1 September 2009 Island of Ireland New Catalogue.indd 1 21/8/09 09:53:43 Copyright © Individual Authors Published by: Interface, University of Ulster ISBN: 978-1-905902-04-0 Copyright notice: All rights reserved by individual authors; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. Individual authors of papers and presentations are soleyl responsible for all materials submitted for this publication. The publisher does not warrant or assume any legal responsibilities for the publication’s content. All opinions expressed in this publication are of the authors and do not reflect those of the publishers. Editorial Team: Kerstin Mey, Grainne Loughran, Cherie Driver Printed by: Graham and Heslip Printer Ltd Design and Layout by Ardmore Advertising Corporate Design by Terry Quigley Web Design: Mark Cullen New Catalogue.indd 2 19/8/09 15:41:49 Contents Acknowledgements .....................................................................................4 Foreword ......................................................................................................6 ISEA2009: The Exhibition Kathy Rae Huffman ......................................................................................7 Ormeau Baths Gallery .................................................................................11 -

The Fidelio Trio Winter Chamber Music Festival at St Patrick's

The Fidelio Trio ARTISTS-IN-RESIDENCE 2014/15 Music Department St Patrick’s College, Drumcondra The Fidelio Trio Darragh Morgan (violin) | Mary Dullea (piano) | Adi Tal (cello) Concert Schedule 2014/15 Wednesday 1 October 2014 Wednesday 25 February 2015 Lunchtime Concert Series Evening Concert St Patrick’s College, 1.15 pm Auditorium, St Patrick’s College, 7.30 pm Mozart – Piano Trio in B flat major K502 Fauré – Piano Trio Op. 120 Michael Nyman – Time Will Pronounce John Buckley – Piano Trio Judith Weir – Piano Trio Two (Irish premiere) Friday - Sunday 5 - 7 December 2014 Schoenberg (arr. Steuermann) – Verklärte Nacht Fidelio Trio Winter Chamber Music Festival at Belvedere House, St Patrick’s College Wednesday 15 April 2015 The Fidelio Trio with Nicholas Daniel (oboe) and Lunchtime Concert Series Meghan Cassidy (viola) (see inset for festival details) St Patrick’s College, 1.15 pm Dorothy Ker – Channel (World premiere) Wednesday 10 December 2014 Mozart – Piano Trio in E major K 542 Lunchtime Concert Series St Patrick’s College, 1.15 pm Wednesday 8 July 2015 Mendelssohn - Variations Concertantes Evening Concert Suk - Ballade & Serenade Auditorium, St Patrick’s College, 7.30 pm John Adams - Road Movies Martin O’Leary – Bluescape Liszt arr. Saint-Saens – Orphée (Poeme Symphonique) Wednesday 21 January 2015 Chausson – Piano Trio in G minor Op. 3 Lunchtime Concert Series St Patrick’s College, 1.15 pm Benedict Schlepper-Connolly – Ekstase II (Irish premiere) Mark Bowden – Airs No Oceans Keep (Irish premiere) Percy Grainger – Colonial Song Free Admission to all concerts The Fidelio Trio Winter Chamber Music Festival at St Patrick’s College 5-7 December 2014 Darragh Morgan (violin) Mary Dullea (piano) Adi Tal (cello) Nicholas Daniel (oboe) Meghan Cassidy (viola) We are delighted to announce our second Fidelio Trio Winter Chamber Music Festival at St Patrick’s College where we have continued to enjoy a wonderful artistic residency since 2012. -

Music Events at Queen's

MUSIC EVENTS AT QUEEN’S SPRING 2018 qub.ac.uk/schools/ael/events Map Key General Information 1 Contact us on 028 9097 5337 facebook.com/creativeartsqub twitter.com/creativeartsqub 5 2 || Seminar www.qub.ac.uk/schools/ael/events 6 4 1 Black Box 4 Whitla Hall || Concert 2 Old McMordie Hall 5 Harty Room Drama and Film Centre (DFC)/ Brian Friel Theatre (OMcMH) McMordie Hall 6 Great Hall, QUB Harty Room Sonic Art Research Centre (SARC) 3 Sonic Lab (SARC) Whitla Hall || Workshop Note: All concert events are free except where stated. However, ALL SARC event tickets must 3 be booked in advance via Eventbrite: tickets are available at the MovingOnMusic website. www.movingonmusic.com Please note: All events are free unless a price is given Spring 2018 Upcoming Events ‘Interactive systems for the Wed 10 Jan 13:00 Thurs 11 Jan 13:10 Wed 17 Jan 13:00 embodied navigation of complex Seminar Old McMordie Hall Concert Harty Room Seminar Sonic Lab piano notation’ ‘From Amhráin Árann – Aran Alex Petcu (percussion) Songs to the Rev. Daniel Pavlos Antoniadis A rare chance to hear this virtuoso instrumentalist in J. Murphy Archive: history, a one-man percussion programme, including Volans’ repatriation, empowerment popular ‘Asanga’ and pieces for a huge array of and the digital frontier’ percussion by Irish and European composers. Dr Deirdre Ní Chonghaile (NUI Galway) Thurs 18 Jan 13:10 Wed 31 Jan 13:00 Concert Sonic Lab Seminar Sonic Lab Pavlos Antoniadis (piano) ‘Performance Without Barriers: Complexity and embodiment: Pavlos Antoniadis Designing for Inclusion in Music’ (piano) in works by Ustvolskaya, Erber, Nono, Takahashi, and Hoban. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Herbert Read to T.S. Eliot: 1 October 1949: Herbert Read Archive, University of Victoria (hereafter HRAUV), HR/TSE-170. 2. Herbert Read, The Contrary Experience: Autobiographies (London, 1963), 353, 350. 3. Isaiah Berlin, The Roots of Romanticism (London, [1965] 2000), 97. 4. For a useful discussion, see: Peter Ryley, Making Another World Possible: Anar- chism, Anti-capitalism and Ecology in Late 19th and Early 20th Century Britain (New York, 2013); Mark Bevir, The Making of British Socialism (Princeton, 2011), 256–277. 5. Martin A. Miller, Kropotkin (Chicago, 1976), 166–167; Rodney Barker, Political Ideas in Modern Britain (London, 1978), 42 passim. 6. H. Oliver, The International Anarchist Movement in Late Victorian London (London, 1983), 136; see also: 92, 132–137. For a discussion of the signifi- cance of the Congress, see: Davide Turcato, Making Sense of Anarchism: Errico Malatesta’s Experiments with Revolution (Basingstoke, 2012), 136–139. 7. W. Tcherkesoff, Let Us Be Just: (An Open Letter to Liebknecht) (London, 1896), 7. 8. The report offered short biographies of Francesco Merlino, Gustav Landauer, Louise Michel, Amilcare Cipriani, Augustin Hamon, Élisée Reclus, Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis, Bernard Lazare, and Peter Kropotkin. N.A., Full Report of the Proceedings of the International Workers’ Congress, London, July and August, 1896 (London, 1896), 67–72. 9. N.A., Full Report of the Proceedings, 21, 17. 10. Matthew S. Adams, ‘Herbert Read and the fluid memory of the First World War: Poetry, Prose, and Polemic’, Historical Research (2014), 1–22; Janet S.K. Watson, Fighting Different Wars: Experience, Memory, and the First World War in Britain (Cambridge, 2004), 226. -

Freedom Press Bookshop

F .~ 5 - - _. _ 4.‘ - _;_L],|._ii_-'- i S‘ »= .;"5"- 1 I". -kWorld Inequality: Origins and Perspectives of the World ZERZAN. J. Elements of Refusal (essays on power and System (ed I. Wallerstein) £4.50 domination) £5.95 it-A Year of Our Lives: Hatfield Main. a colliery in the great ZIESING. M. The Scarlet Q: Anarchy, Religion and I coal strike £2.40 the Cult of Science (illustrated). Includes essay on Northern Ireland. ‘No Statist Solutions’ £4.50 BOOKS IN STOCK 1991-92 Section 2: Other Titles FREEDOM PRESS has been for the past 100 years publishers FREEDOM Pnsss BOOKSHOP in Angel Alley and distributors of the alternative social and political press. 84b Whitechapel High Street, London E1 7QX. Tel: 071- As well as Freedom fortnightly (founded 1886) and the 247 9249. Open Monday to Friday 10.00am to 6.00pm, new quarterly journal The Raven (1987). Freedom Press Saturday 10.00am to 5.00pm. irThe Anarchist Reader (ed. Woodcock) £4.95 JOLL. James. The Anarchists (2nd edition) £9.95 are publishers of more some fifty titles dealing not only Underground Aldgate East (Whitechapel Art Gallery exit). AVRICH. Paul. KROPOTKIN. Peter. with the philosophy of anarchism but with its practical An American Anarchist (life of Voltairine de Cleyre) +£25.50 Memoirs of a Revolutionist (intro by Nicolas Buses 15, 25, 40 and 253 pass close by. Many other Anarchist Portraits +£17.95 Walter. illustrated) £8.95 application to the problems of modern society. Such titles routes serve Aldgate Bus Station (500 yards). The Haymarket Tragedy £6.25 Memoirs of a Revolutionist (abridged) £6.95 as Anarchists in the Spanish Revolution by José Peirats. -

Anarchism and Religion

Anarchism and Religion Nicolas Walter 1991 For the present purpose, anarchism is defined as the political and social ideology which argues that human groups can and should exist without instituted authority, and especially as the historical anarchist movement of the past two hundred years; and religion is defined as the belief in the existence and significance of supernatural being(s), and especially as the prevailing Judaeo-Christian systemof the past two thousand years. My subject is the question: Is there a necessary connection between the two and, if so, what is it? The possible answers are as follows: there may be no connection, if beliefs about human society and the nature of the universe are quite independent; there may be a connection, if such beliefs are interdependent; and, if there is a connection, it may be either positive, if anarchism and religion reinforce each other, or negative, if anarchism and religion contradict each other. The general assumption is that there is a negative connection logical, because divine andhuman authority reflect each other; and psychological, because the rejection of human and divine authority, of political and religious orthodoxy, reflect each other. Thus the French Encyclopdie Anarchiste (1932) included an article on Atheism by Gustave Brocher: ‘An anarchist, who wants no all-powerful master on earth, no authoritarian government, must necessarily reject the idea of an omnipotent power to whom everything must be subjected; if he is consistent, he must declare himself an atheist.’ And the centenary issue of the British anarchist paper Freedom (October 1986) contained an article by Barbara Smoker (president of the National Secular Society) entitled ‘Anarchism implies Atheism’.