Julius Ca Esa R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Herodotos Project (OSU-Ugent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography

Faculty of Literature and Philosophy Julie Boeten The Herodotos Project (OSU-UGent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography Barbarians in Strabo’s ‘Geography’ (Abii-Ionians) With a case-study: the Cappadocians Master thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Linguistics and Literature, Greek and Latin. 2015 Promotor: Prof. Dr. Mark Janse UGent Department of Greek Linguistics Co-Promotores: Prof. Brian Joseph Ohio State University Dr. Christopher Brown Ohio State University ACKNOWLEDGMENT In this acknowledgment I would like to thank everybody who has in some way been a part of this master thesis. First and foremost I want to thank my promotor Prof. Janse for giving me the opportunity to write my thesis in the context of the Herodotos Project, and for giving me suggestions and answering my questions. I am also grateful to Prof. Joseph and Dr. Brown, who have given Anke and me the chance to be a part of the Herodotos Project and who have consented into being our co- promotores. On a whole other level I wish to express my thanks to my parents, without whom I would not have been able to study at all. They have also supported me throughout the writing process and have read parts of the draft. Finally, I would also like to thank Kenneth, for being there for me and for correcting some passages of the thesis. Julie Boeten NEDERLANDSE SAMENVATTING Deze scriptie is geschreven in het kader van het Herodotos Project, een onderneming van de Ohio State University in samenwerking met UGent. De doelstelling van het project is het aanleggen van een databank met alle volkeren die gekend waren in de oudheid. -

Wars and Battles of Ancient Rome

Wars and Battles of Ancient Rome Battle summaries are from Harbottle's Dictionary of Battles, published by Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1904. Rise of Rome—753 to 3911 B.C. The rise of Rome from a small Latin city to the dominant power in Italy Battle of Description Sabines According to legend, a year after the Romans kidnapped their wives from the neighboring Sabines, the (Kingdom) tribes returned to take vengeance. The fighting however, was stopped by the young wives who ran in B.C. 750 between the warring parties and begged that their fathers, brothers and husbands cease making war upon each other. The Sabine and Roman tribes were henceforth united. Alba Longa After a long siege, Alba was finally taken by strategm. With the fall of Alba, its father-city, Rome was (Kingdom) the undisputed leading city of the Latins. The inhabitants of Alba were resettled in Rome on the caelian B.C. 650 Hill. Sublican Lars Porsenna, king of Clusium was marching toward Rome, planning to restore the exiled Tarquins to Bridge the Roman throne. As his army descended on Rome from the opposite side of the Tiber, roman soldiers (Tarquinii) worked furiously to destroy the wooden bridge. Horatius and two other soldiers single-handedly fended B.C. 509 off Porsenna's army until the bridge could be destroyed. Lake Regillus Fought B.C. 497, the first authentic date in the history of Rome. The details handed down, however, (Tarquinii) belong to the domain of legend rather than to that of history. According to the chroniclers, this was the B.C. -

![The History of Rome, Vol. 6 [10 AD]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5302/the-history-of-rome-vol-6-10-ad-1975302.webp)

The History of Rome, Vol. 6 [10 AD]

The Online Library of Liberty A Project Of Liberty Fund, Inc. Titus Livius (Livy), The History of Rome, Vol. 6 [10 AD] The Online Library Of Liberty This E-Book (PDF format) is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a private, non-profit, educational foundation established in 1960 to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. 2010 was the 50th anniversary year of the founding of Liberty Fund. It is part of the Online Library of Liberty web site http://oll.libertyfund.org, which was established in 2004 in order to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. To find out more about the author or title, to use the site's powerful search engine, to see other titles in other formats (HTML, facsimile PDF), or to make use of the hundreds of essays, educational aids, and study guides, please visit the OLL web site. This title is also part of the Portable Library of Liberty DVD which contains over 1,000 books and quotes about liberty and power, and is available free of charge upon request. The cuneiform inscription that appears in the logo and serves as a design element in all Liberty Fund books and web sites is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash, in present day Iraq. To find out more about Liberty Fund, Inc., or the Online Library of Liberty Project, please contact the Director at [email protected]. -

Gaius Marius

GAIUS MARIUS BIOGRAPHY WORKBOOK Gaius Marius GAIUS MARIUS (157-86 B.C.E.) Gaius Marius was at this time 2. In what township was Gaius forty-eight years old. Two-thirds of Marius born? his life were over, and a name which _________________________________ was to sound throughout the world _________________________________ and be remembered through all ages, _________________________________ had as yet been scarcely heard of _________________________________ beyond the army and the political _________________________________ clubs in Rome. Marius forced his way steadily 1. How old was Gaius Marius when upward, by his mere soldier-like he began to enter the public eye? qualities, to the rank of military _________________________________ tribune. Rome, too, had learnt to know _________________________________ him, for he was chosen tribune of the _________________________________ people the year after the murder of _________________________________ Gaius Gracchus. Being a self-made _________________________________ man, he belonged naturally to the popular party (the Populares). While Gaius Marius was born at in office he gave offense in some way Arpinum, a Latin township, seventy to the men in power, and was called miles from the capital, in the year 157 before the Senate to answer for B.C.E. His father was a small farmer, himself. But he had the right on his and he was himself bred to the plow. side, it is likely, for they found him Gaius Marius joined the army early, stubborn and impertinent, and they and soon attracted notice by his could make nothing of their charges punctual discharge of his duties. against him. He was not bidding at In a time of growing looseness, this time, however, for the support of Marius was strict himself in keeping the mob. -

Final Playbook

COIN Series, Volume VI PLAYBOOKby Andrew Ruhnke and Volko Ruhnke TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Germanic Role and Strategy ................... 2 4. Credits .................................... 11 2. Design Notes ............................... 2 6. New Card List .............................. 12 3. Event Text and Notes ......................... 4 © 2018 GMT Games, LLC • P.O. Box 1308, Hanford, CA 93232-1308 • www.GMTGames.com 2 Ariovistus Auguries. Your need to hold Control of the Germanic Tribes and the slowness of your columns of colonists will hold your heart close to the Rhenus. But consider a deeper thrust into Gaul if opportune— your enemies will not expect it! Design Notes Why Ariovistus? An earlier version of these notes from Volko appeared on the Inside GMT Games blog in 2016. It looks at why we thought Falling Sky deserved an Ariovistus expansion and how we chose what to include. Quotations from Caesar’s Gallic War are translations by Carolyn Hammond, Oxford University Press. When Andrew and I endeavored to set a COIN Series volume in ancient Gaul, we immediately decided on the latter years of Caesar’s campaigns there. My own starting point was a suggestion from David Dockter that I try my hand at a design on “Roman-style counterinsur- Germanic Role and Strategy gency”, that is to say, counter-revolt. Andrew suggested the portion Your Nation. You are Ariovistus, king of the Suebi, and can call of Caesar’s Commentaries that more concerned revolt than conquest. upon the numbers and warlike spirit of the greatest tribe of Germania. The latter period of mobilizing confederations of tribes—Ambiorix Nearby Gaul is divided and the Romans mere newcomers across the of the Belgic Eburones (in 53BC) and Vercingetorix of the Celtic Alps. -

Supporting Information

Supporting Information McConnell et al. 10.1073/pnas.1721818115 Fig. S1. Nearly contiguous annual average (black) and 11-y median-filtered (red) lead and related measurements in the NGRIP2 ice cores. Shown are 1100 BCE to 800 CE records of (A) total lead concentration, (B) enrichment relative to cerium, (C) estimated background lead concentration, and (D) nonbackground lead concentration and lead flux. McConnell et al. www.pnas.org/cgi/content/short/1721818115 1of8 Fig. S2. Differences between ice-core chronologies. Differences between the new DRI_NGRIP2 ice-core chronology based on multiparameter, annual-layer counting and the independent IntCal13 age scale based on cosmogenic nuclides (1) at 137 volcanic tie points in both the GRIP and NGRIP2 ice-core records. Gray shading shows 1 σ uncertainties from mapping GRIP cosmogenic nuclides (10Be) on to IntCal13 (14C), suggesting <2-y uncertainties (1 σ) in the new chronology during classical antiquity. The DRI_NGRIP2 chronology differs from the NEEM_2011_S1 chronology (2) by <2 y throughout antiquity, well within the stated uncertainties of that chronology. 1. Adolphi F, Muscheler R (2016) Synchronizing the Greenland ice core and radiocarbon timescales over the Holocene–Bayesian wiggle-matching of cosmogenic radionuclide records. Clim Past 12:15–30. 2. Sigl M, et al. (2015) Timing and climate forcing of volcanic eruptions for the past 2,500 years. Nature 523:543–549. Fig. S3. Differences between the original GRIP and DRI_NGRIP2 ice-core chronologies. The former, used to interpret the 18 previously published discrete measurements in the GRIP core of copper (1) and lead concentrations (2, 3), as well as lead isotope ratios (2), was incorrect by 20–30 y during classical antiquity. -

Computer Analysis of Human Belligerency

mathematics Article Computer Analysis of Human Belligerency José A. Tenreiro Machado 1,† , António M. Lopes 2,*,† and Maria Eugénia Mata 3,† 1 Department of Electrical Engineering, Institute of Engineering, Polytechnic of Porto, Rua Dr. António Bernardino de Almeida, 431, 4249-015 Porto, Portugal; [email protected] 2 LAETA/INEGI, Faculty of Engineering, University of Porto, Rua Dr. Roberto Frias, 4200-465 Porto, Portugal 3 Nova SBE, Nova School of Business and Economics (Faculdade de Economia da Universidade Nova de Lisboa), Rua da Holanda, 1, 2775-405 Carcavelos, Portugal; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally to this work. Received: 13 June 2020; Accepted: 20 July 2020; Published: 22 July 2020 Abstract: War is a cause of gains and losses. Economic historians have long stressed the extreme importance of considering the economic potential of society for belligerency, the role of management of chaos to bear the costs of battle and casualties, and ingenious and improvisation methodologies for emergency management. However, global and inter-temporal studies on warring are missing. The adoption of computational tools for data processing is a key modeling option with present day resources. In this paper, hierarchical clustering techniques and multidimensional scaling are used as efficient instruments for visualizing and describing military conflicts by electing different metrics to assess their characterizing features: time, time span, number of belligerents, and number of casualties. Moreover, entropy is adopted for measuring war complexity over time. Although wars have been an important topic of analysis in all ages, they have been ignored as a subject of nonlinear dynamics and complex system analysis. -

An Economic History of Rome Second Edition Revised

An Economic History of Rome Second Edition Revised Tenney Frank Batoche Books Kitchener 2004 Originally published in 1927. This edition published 2004 Batoche Books Limited [email protected] Contents Preface ...........................................................................................................................5 Chapter 1: Agriculture in Early Latium.........................................................................6 Chapter 2: The Early Trade of Latium and Etruria .....................................................14 Chapter 3: The Rise of the Peasantry ..........................................................................26 Chapter 4: New Lands For Old ...................................................................................34 Chapter 5: Roman Coinage .........................................................................................41 Chapter 6: The Establishment of the Plantation..........................................................52 Chapter 7: Industry and Commerce ............................................................................61 Chapter 8: The Gracchan Revolution..........................................................................71 Chapter 9: The New Provincial Policy........................................................................78 Chapter 10: Financial Interests in Politics ..................................................................90 Chapter 11: Public Finances......................................................................................101 -

Retreats and Withdrawals in Republican Roman Warfare Daniel Morgan, BA (Hons) (Newcastle)

Retreats and Withdrawals in Republican Roman Warfare Daniel Morgan, BA (Hons) (Newcastle) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Classical Langugages May 2020 This research was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship Retreats and Withdrawals in Republican Roman Warfare 2020 Statement of Originality I hereby certify that the work embodied in the thesis is my own work, conducted under normal supervision. The thesis contains no material which has been accepted, or is being examined, for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made. I give consent to the final version of my thesis being made available worldwide when deposited in the University’s Digital Repository, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968 and any approved embargo. Signature: D. Morgan Date: 5 May 2020 Daniel Morgan University of Newcastle 2 Retreats and Withdrawals in Republican Roman Warfare 2020 Acknowledgements I would first and foremost like to thank my primary supervisor, Dr. Jane Bellemore, for her direction and assistance during all stages of my studies, and especially for her assistance with this thesis. I wish I had a sestertius for each gratuitous or ill-considered question I bombarded her with. Even so, I received a considered and useful response to each and every one. She has given me a great deal of feedback on numerous drafts of this thesis, and I would not have been able to do it without her guidance. -

Roman Soldier Vs Germanic Warrior: 1St Century AD Free

FREE ROMAN SOLDIER VS GERMANIC WARRIOR: 1ST CENTURY AD PDF Lindsay Powell,Professor of History Peter Dennis | 80 pages | 20 May 2014 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781472803498 | English | United Kingdom Chronology of warfare between the Romans and Germanic tribes - Wikipedia Marcomannic Wars — participating Roman units. Roman—Alemannic Wars. Gothic War — The nature of these wars varied through time between Roman conquest, Germanic uprisings and later Germanic invasions in the Roman Empire that started in the late 2nd century BC. The series of conflicts, which began in the 5th century under the Western Roman Emperor Honoriuswas one of many factors which led to the ultimate downfall of the Western Roman Soldier vs Germanic Warrior: 1st Century AD Empire. The territories which remained under Byzantine control were called "Romania" today's Italian region of Romagna in northeastern Italy and had its stronghold in the Exarchate of Ravenna, icluding Rome. The support Pepin enjoyed from the papacy was decisive. Because of the Roman Soldier vs Germanic Warrior: 1st Century AD this move represented for the new king of the Franks, an agreement between Pepin and Stephen II settled, in exchange Roman Soldier vs Germanic Warrior: 1st Century AD the formal royal anointing, the descent of the Franks in Italy. Inthe Lombard army, deployed in defence of the Locks in Val di Susawas defeated by the Franks. Aistulf, perched in Pavia, had to accept a treaty that required the delivery of hostages and territorial concessions, but two years later resumed the war against the pope, who in turn called on the Franks. Defeated again, Aistulf had to accept much harsher conditions: Ravenna was returned not to the Byzantinesbut to the pope, increasing the core area of the Patrimony of St. -

Between Amazons and Sabines: a Historical Approach to Women And

Volume 92 Number 877 March 2010 Between Amazons and Sabines: a historical approach to women and war Ire`ne Herrmann and Daniel Palmieri* Ire'ne Herrmann is associate professor of modern history at the University of Fribourg and lecturer of Swiss history at the University of Geneva. Daniel Palmieri is historical research officer at the ICRC. Abstract Today, war is still perceived as being the prerogative of men only. Women are generally excluded from the debate on belligerence, except as passive victims of the brutality inflicted on them by their masculine contemporaries. Yet history shows that through the ages, women have also played a role in armed hostilities, and have sometimes even been the main protagonists. In the present article, the long history and the multiple facets of women’s involvement in war are recounted from two angles: women at war (participating in war) and women in war (affected by war). The merit of a gender- based division of roles in war is then examined with reference to the ancestral practice of armed violence. Since time immemorial, war has been an integral part of the history of human- kind.1 Yet this age-old activity seems to have been the preserve of only part of humankind, since war is still perceived as being essentially a male affair. Many arguments have been put forward to explain this male predominance. ‘Innate violence’, ‘the predator instinct’, or even ‘the death wish’, traits believed to be particularly developed in men, are said to explain their propensity to go to war. Cultural traditions which instil the cult of war into boys from an early * The views expressed in this article reflect only the authors’ opinions. -

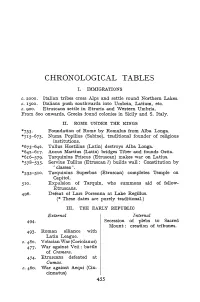

Chronological Tables

CHRONOLOGICAL TABLES I. IMMIGRATIONS c. 2000. Italian tribes cross Alps and settle round Northern Lakes. c. 1500. Italians push southwards into Umbria, Latium, etc. c. 900. Etruscans settle in Etruria and Western Umbria. From 800 onwards, Greeks found colonies in Sicily and S. Italy. II. ROME UNDER THE KINGS *753- Foundation of Rome by Romulus from Alba Longa. * 71 5-673. Numa Popilius (Sabine), traditional founder of religious institutions. *673-642. Tullus Hostilius (Latin) destroys Alba Longa. Ancus Martius (Latin) bridges Tiber and founds Ostia. *6i 6-579. Tarquinius Priscus (Etruscan) makes war on Latius. *5 78-53 5. Servius Tullius (Etruscan ?) builds wall : Constitution by ' classes '. *535~5io. Tarquinius Superbus (Etruscan) completes Temple on Capitol. 510. Expulsion of Tarquin, who summons aid of fellow- Etruscans. 496. Defeat of Lars Porsenna at Lake Regillus. (* These dates are purely traditional.) III. THE EARLY REPUBLIC External Internal 494. Secession of plebs to Sacred Mount : creation of tribunes. 493- Roman alliance with Latin League. c. 480. Volscian War (Coriolanus) 477- War against Veii : battle of Cremera. 474- Etruscans defeated at Cumae. c. 460. War against Aequi (Cin- cinnatus) 455 456 THE ROMAN REPUBLIC External Internal 451- Decemviri begin tabulation of Laws. 450. Decemviri (Appius Claudius) de posed. 449- Valerio-Horatian Laws : rights to plebeians. 445- Lex Canuleia : permitting inter marriage of Orders. 431- Aequi defeated at Mt. Algidus. 396. Capture of Veii by Camil- lus. 390. Rome sacked by Gauls. 376. Licinian proposals : violent strife results. 367- Licinian proposals become law : one consul plebeian, etc. 360-50. Gallic Invasions. 287. Lex Hortensia gives plebescita authority of law.