FULL ISSUE (56 Pp., 2.4 MB PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Study of Jining Religions in the Late Imperial and Republican Periods

www.ccsenet.org/ach Asian Culture and History Vol. 4, No. 2; July 2012 Pluralism, Vitality, and Transformability: A Case Study of Jining Religions in the Late Imperial and Republican Periods Jinghao Sun1 1 History Department, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China Correspondence: Jinghao Sun, History Department, East China Normal University, Shanghai 200241, China. Tel: 86-150-2100-6037. E-mail: [email protected] Received: March 12, 2012 Accepted: June 4, 2012 Online Published: July 1, 2012 doi:10.5539/ach.v4n2p16 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ach.v4n2p16 The final completion and publication of this article was supported by the New Century Program to Promote Excellent University Talents (no.: NECJ-10-0355). Abstract This article depicts the dynamic demonstrations of religions in late imperial and republican Jining. It argues with evidences that the open, tolerant and advanced urban circumstances and atmosphere nurtured the diversity and prosperity of formal religions in Jining in much of the Ming and Qing periods. It also argues that the same air and ethos enabled Jining to less difficultly adapt to the West-led modern epoch, with a notable result of welcoming Christianity, quite exceptional in hinterland China. Keywords: Jining, religions, urban, Grand Canal, hinterland, Christianity I. Introduction: A Special Case beyond Conventional Scholarly Images It seems a commonplace that intellectual and religious beliefs and practices in imperial Chinese inlands were conservative, which encouraged orthodoxy ideology or otherwise turned to heretic sectarianism. It is also commonplace that in the post-Opium War modern era, hinterland China, while being sluggishly appropriated into Westernized modernization, persistently resisted the penetration of Western values and institutes including Christianity. -

Apr 1990 Vol 14 No 2

EVANGELICAL REVIEW OF THEOLOGY VOLUME 14 Volume 14 • Number 2 • April 1990 Evangelical Review of Theology WORLD EVANGELICAL FELLOWSHIP Theological Commission p. 99 The Doctrine of Regeneration in the Second Century Victor K. Downing Printed with permission Having been raised within the evangelical community since birth, and having ‘gone forward’ at a Billy Graham crusade at the age of nine, there has never been any question in my mind as to what it means to be ‘born again’. However, since having begun to dabble in historical theology, the question has often occurred to me: ‘I wonder if Ignatius or Justin or Irenaeus understood John 3:7 as I understand it, and if not, why not?’. The purpose of this paper is not to critique twentieth-century evangelicalism’s doctrine of regeneration but to ponder this issue: if the idea of the ‘new birth’ is as foundational to the Christian faith, and the experience of the ‘new birth’ as central to the Christian life, as we evangelicals believe them to be; and if our (evangelical) view of regeneration is correct, as I presume most of us are convinced that it is; then why is it not more evident in the traditions of the sub-apostolic and early patristic Church? There are two reasons that I have chosen to examine the second century in particular. First, the person of Irenaeus provides us with an appropriate and convenient focal point. He lived and wrote at the close of the period and was the pre-eminent systematic theologian of the century and arguably the first in the history of the Church. -

Academic Calendar

> > > ACADEMIC CALENDAR 2005-2006 ACADEMIC CALENDAR FALL SEMESTER 2005 August 5 ExL registration begins for students within an 85-mile radius of the Kentucky Campus for fall 2005 31-Sept. 2 Orientation and Registration for new students, Kentucky September 6 Classes begin 6 Opening Convocation, Kentucky 8 Opening Convocation, Florida 13, 15, 20, 22 Holiness Chapels 16 Last day to drop a course with a refund; close of all registration for additional classes 30 Payment of fees due in Business Office October 18-21 Kingdom Conference Speakers: Asbury Community 21 Last day to withdraw from the institution with a prorated refund; last day to drop a course without a grade of “F” November 3-4 Ryan Lectures Speaker: • Dr. Miroslav Volf, Professor of Systematic Theology, Yale University Divinity School 18 Last day to remove incompletes (spring and summer) 21 - 25 Fall Reading Week December 4 Advent Service 6 Baccalaureate and Commencement, Wilmore 12-16 Final Exams 16 Semester ends JANUARY TERM 2006 January 3 Classes begin 5 Last day to drop a course with a refund; close of registration for addition al courses 9 ExL registration begins for students within an 85-mile radius of the Kentucky Campus for spring 2006 13 Last day to drop a course without a grade of “F” 16 Martin Luther King Day, No Classes 20 Payment of fees due in Business Office 27 Final exams, term ends Jan. 30 - Feb. 2 2006 Ministry Conference 2 Academic Calendar 3 SPRING SEMESTER 2006 February 3 Spring Orientation 6 Classes begin 15-16 Beeson Lectures Speaker: • The Reverend Jim Garlow, Senior Pastor at Skyline Church, San Diego, CA 17 Last day to drop a course with refund; close of all registration for additional courses March 3 Payment of fees due in the Business Office 9, 10 Theta Phi Lectures Speaker: • Dr. -

Bernard Quaritch Ltd Hong Kong

Bernard Quaritch Ltd CHINA IN PRINT 22 – 24 November 2013 Hong Kong BERNARD QUARITCH LTD. 40 SOUTH AUDLEY STREET , LONDON , W1K 2PR Tel. : +44 (0)20 7297 4888 Fax : +44 (0)20 7297 4866 E-mail : [email protected] or [email protected] Website : www.quaritch.com Mastercard and Visa accepted. If required, postage and insurance will be charged at cost. Other titles from our stock can be browsed/searched at www.quaritch.com Bankers : Barclays Bank PLC, 50 Pall Mall, PO Box 15162, London SW1A1QA Sort code : 20-65-82 Swift code : BARCGB22 Sterling account IBAN: GB98 BARC 206582 10511722 Euro account IBAN: GB30 BARC 206582 45447011 US Dollar account IBAN: GB46 BARC 206582 63992444 VAT number : GB 840 1358 54 © Bernard Quaritch Ltd 2013 Front cover: item 5 1. AH FONG . The Sino-Japanese Hostilities Shanghai. N.p., 1937 . Album of 110 gelatin silver prints, 2 in a panoramic format approx. 2 x 7½ inches (4.7 x 19 cm.) the remainder 2¼ x 3½ inches (5.5 x 8.3 cm.), a few titled in the negatives, five images including one panorama toned red; all prints numbered on mounts according to a printed index attached at beginning of album (folded), with captions to all images and photographer’s credit ah fong photographer 819 Nanking Road Shanghai; black paper boards, the upper cover decorated in silver, depicting a city skyline ravaged by bombs and tanks with bombers and a warship, black cord tie, oblong 8vo. £3800 / HK$ 47,500 Following the Mukden (or Manchurian) Incident in September 1931, when the Japanese invaded the north-eastern part of China, the Chinese called for a boycott of Japanese goods. -

Anglicans in China

ANGLICANS IN CHINA A History of the Zhonghua Shenggong Hui (Chung Hua Sheng Kung Huei) by G.F.S. Gray with editorial revision by Martha Lund Smalley The Episcopal China Mission History Project 1996 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements . ..... ...... ..... ...... ..... ...... ..... ...... ..... ............ .......................... ............ 1 Editor's foreword ..... ..... ...... ..... ...... ..... ...... ..... ...... ..... ............ .......................... ............ 2 List of illustrations ... ..... ...... ..... ...... ..... ...... ..... ...... ..... ............ .......................... ............ 3 Preface by G.F.S. Gray. ...... ..... ...... ..... ...... ..... ...... ..... ............ .......................... ............ 4 Overview and chronology of the period 1835-1910 ... ..... ............ .......................... ............ 5 Overview of the period 1911-1927 .... ..... ...... ..... ...... ..... ............ .......................... ............ 20 Diocesan histories 1911-1927 Hong Kong and South China ...... ..... ...... ..... ...... ..... ............ .......................... ............ 25 Fujian (Fukien) .. ..... ...... ..... ...... ..... ...... ..... ...... ..... ............ .......................... ............ 26 Zhejiang (Chekiang) ...... ..... ...... ..... ...... ..... ...... ..... ............ .......................... ............ 27 Guangxi-Hunan (Kwangsi-Hunan) .... ...... ..... ...... ..... ............ .......................... ............ ............ 28 Shanghai .... ...... .... -

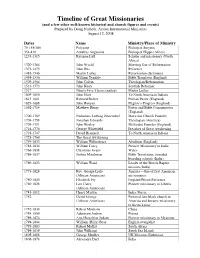

Timeline of Great Missionaries

Timeline of Great Missionaries (and a few other well-known historical and church figures and events) Prepared by Doug Nichols, Action International Ministries August 12, 2008 Dates Name Ministry/Place of Ministry 70-155/160 Polycarp Bishop of Smyrna 354-430 Aurelius Augustine Bishop of Hippo (Africa) 1235-1315 Raymon Lull Scholar and missionary (North Africa) 1320-1384 John Wyclif Morning Star of Reformation 1373-1475 John Hus Reformer 1483-1546 Martin Luther Reformation (Germany) 1494-1536 William Tyndale Bible Translator (England) 1509-1564 John Calvin Theologian/Reformation 1513-1573 John Knox Scottish Reformer 1517 Ninety-Five Theses (nailed) Martin Luther 1605-1690 John Eliot To North American Indians 1615-1691 Richard Baxter Puritan Pastor (England) 1628-1688 John Bunyan Pilgrim’s Progress (England) 1662-1714 Matthew Henry Pastor and Bible Commentator (England) 1700-1769 Nicholaus Ludwig Zinzendorf Moravian Church Founder 1703-1758 Jonathan Edwards Theologian (America) 1703-1791 John Wesley Methodist Founder (England) 1714-1770 George Whitefield Preacher of Great Awakening 1718-1747 David Brainerd To North American Indians 1725-1760 The Great Awakening 1759-1833 William Wilberforce Abolition (England) 1761-1834 William Carey Pioneer Missionary to India 1766-1838 Christmas Evans Wales 1768-1837 Joshua Marshman Bible Translation, founded boarding schools (India) 1769-1823 William Ward Leader of the British Baptist mission (India) 1773-1828 Rev. George Liele Jamaica – One of first American (African American) missionaries 1780-1845 -

The Dharma Through a Glass Darkly: on the Study of Modern

‧46‧聖嚴研究 Xian, this research will make a comparative study between the travel literature works of Master Sheng Yen and Fa Xian’s Fo- The Dharma Through guo-ji. This paper will be divided into two parts, the first part will a Glass Darkly: make an observation and analysis on the dialogue which occurred between Master Sheng Yen and Fa Xian through their writing and On the Study of Modern Chinese will deal with the following subjects: how the dialogue between Buddhism Through Protestant two great monks were made, the way the dialogue carried on, and * the contents of the dialogue. The second part of this paper will Missionary Sources focus on the dialectic speeches which appeared in many places of the books, including: see / not to see, sthiti / abolish, past / future. These dialectic dialogues made Master Sheng Yen’s traveling Gregory Adam Scott Ph.D. Candidate, Department of Religion, Columbia University writings not only special in having his own characteristic but also made his traveling writings of great importance and deep meanings in the history of Chinese Buddhist literature. ▎Abstract KEYWORDS: Master Sheng Yen, travel literature, Fa Xian, Fo- European-language scholarship on Buddhism in nineteenth— guo-ji and early twentieth—century China has traditionally relied heavily on sources originally produced by Christian missionary scholars. While the field has since broadened its scope to include a wide variety of sources, including Chinese-language and ethnographic studies, missionary writings continue to be widely cited today; * T his paper is based on presentations originally given at the North American Graduate Student Conference on Buddhist Studies in Toronto in April 2010, and at the Third International Conference of the Sheng Yen Educational Foundation in Taipei in May 2010. -

Calvin Wilson Mateer, Forty-Five Years a Missionary In

Calvin Wilson <A Bio seraph if DANIEL W. HER ^ . 2-. / . 5 O / J tilt aiitoiojif/ii J, PRINCETON, N. J. //^ Purchased by the Hamill Missionary Fund. nv„ BV 3427 .M3 F5 Fisher, Daniel Webster, 183( -1913. Calvin Wilson Mateer CALVIN WILSON MATEER C. W. MATEER • »r \> JAN 301913 y ^Wmhi %^ Calvin Wilson Mateer FORTY-FIVE YEARS A MISSIONARY IN SHANTUNG, CHINA A BIOGRAPHY BY DANIEL W. FISHER PHILADELPHIA THE WESTMINSTER PRESS 1911 Copyright, 191 i, by The Trustees of the Presbyterian Board of Publication and Sabbath School Work Published September, 191 i AA CONTENTS Introduction 9 CHAPTER I The Old Home ^S ^ Birth—The Cumberland Valley—Parentage—Broth- Grandfather—Re- ers and Sisters, Father, Mother, In the moval to the "Hermitage"—Life on the Farm— Home—Stories of Childhood and Youth. CHAPTER II The Making of the Man 27 Native Endowments—Influence of the Old Home— Schoolmaster—Hunterstown Academy- \j Country Teaching School—Dunlap's Creek Academy—Pro- Recollections fession of Rehgion—Jefferson College— of 1857— of a Classmate—The Faculty—The Class '^ Semi-Centennial Letter. CHAPTER III Finding His Life Work 40 Mother and Foreign Missions—Beaver Academy- Theological Decision to be a Minister—Western Seminary—The Faculty—Revival—Interest in Mis- sions—Licentiate—Considering Duty as to Missions- Decision—Delaware, Ohio—Delay in Going—Ordi- nation—Marriage—Going at Last. CHAPTER IV • * ^' Gone to the Front . • Hardships Bound to Shantung, China—The Voyage— for Che- and Trials on the Way—At Shanghai—Bound Shore- foo—Vessel on the Rocks—Wanderings on to Deliverance and Arrival at Chefoo—By Shentza Tengchow. -

8 Reaching the Unreached Sudan?

REACHING THE UNREACHED SUDAN BELT: GUINNESS, KUMM AND THE SUDAN-PIONIER-MISSION by CHRISTOF SAUER submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF THEOLOGY in the subject MISSIOLOGY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA PROMOTER: DR J REIMER JOINT PROMOTER: DR K FIEDLER NOVEMBER 2001 ************* Scripture taken from the Holy Bible, New International Version®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Society. Used by permission of Internatio nal Bible Society. "NIV" and "New International Version" are trademarks registered in the United States Patent and Trademark office by International Bible Society. 2 Summary Reaching the unreached Sudan Belt: Guinness, Kumm and the Sudan-Pionier-Mission by C Sauer Degree: DTh - Doctor of Theology Subject: Missiology Promoter: DrJReimer Joint Promoter: Dr K Fiedler This missiological project seeks to study the role of the Guinnesses and Kumms in reaching the Sudan Belt, particularly through the Sudan-Pionier-Mission (SPM) founded in 1900. The term Sudan Belt referred to Africa between Senegal and Ethiopia, at that period one of the largest areas unreached by Christian missionaries. Grattan Guinness (1835-1910) at that time was the most influential promoter of faith missions for the Sudan. The only initiative based in Germany was the SPM, founded by Guinness, his daughter Lucy (1865-1906), and her German husband Karl Kumm (1874-1930). Kumm has undeservedly been forgotten, and his early biography as a missionary and explorer in the deserts of Egypt is here brought to light again. The early SPM had to struggle against opposition in Germany. Faith missions were considered unnecessary, and missions to Muslims untimely by influential representatives of classical missions. -

This Is a Complete Transcript of the Oral History Interview with Arthur Frederik Glasser (CN 421, T4) for the Billy Graham Center Archives

This is a complete transcript of the oral history interview with Arthur Frederik Glasser (CN 421, T4) for the Billy Graham Center Archives. No spoken words that were recorded are omitted. In a very few cases, the transcribers could not understand what was said, in which case “[unclear]” was inserted. Also, grunts and verbal hesitations such as "ah" or "um" are usually omitted. Readers of this transcript should remember that this is a transcript of spoken English, which follows a different rhythm and even rule than written English. ... Three dots indicate an interruption or break in the train of thought within the sentence on the part of the speaker. .... Four dots indicate what the transcriber believes to be the end of an incomplete sentence. ( ) Words in parentheses are asides made by the speaker. [ ] Words in brackets are comments by the transcriber. This transcript was made by Bob Shuster and Kevin Emmert and was completed in April 2011. Please note: This oral history interview expresses the personal memories and opinions of the interviewee and does not necessarily represent the views or policies of the Billy Graham Center Archives or Wheaton College. © 2017. The Billy Graham Center Archives. All rights reserved. This transcript may be reused with the following publication credit: Used by permission of the Billy Graham Center Archives, Wheaton College, Wheaton, IL. BGC Archives CN 421, T4 Transcript - Page 2 Collection 421, Tape 4. Oral history interview with Arthur Frederick Glasser by Bob Shuster on April 17, 1995. SHUSTER: This is an interview with Dr. Arthur Glasser by Robert Shuster for the Archives of Billy Graham Center. -

Kongsberg, Norwegen 1883-1975) : Diplomat Biographie 1920 Nicolai Aall Ist Generalkonsul Des Norwegischen Konsulats in Shanghai

Report Title - p. 1 of 11 Report Title Aall, Nicolai (Kongsberg, Norwegen 1883-1975) : Diplomat Biographie 1920 Nicolai Aall ist Generalkonsul des norwegischen Konsulats in Shanghai. [Wik] 1923 Nicolai Aall ist Chargé d'affaires der norwegischen Gesandtschaft in Beijing. [Wik] 1928-1938 Nicolai Aall ist Gesandter der norwegischen Gesandtschaft in Beijing. [Norw2] 1945-1949 Nicolai Aall ist Botschafter der norwegischen Botschaft in Beijing. [Norw2] Akre, Helge = Akre, Helge Skyrud (Oslo 1903-1986) : Diplomat, Jurist, Übersetzer Biographie 1963-1966 Helge Akre ist Botschafter der norwegischen Botschaft in Beijing. [Wik] Algard, Ole (Gjesdal, Norwegen 1921-1995 Valer, Ostfold) : Diplomat Biographie 1967-1969 Ole Algard ist Botschafter der norwegischen Botschaft in Beijing. [Norw2] Anda, Torleif (1921-2013) : Norwegischer Diplomat Biographie 1975-1979 Torleif Anda ist Botschafter der norwegischen Botschaft in Beijing. [Norw2] Arnesen, Arne (Moss 1928-2010 Oslo) : Diplomat Biographie 1982-1987 Arne Arnesen ist Botschafter der norwegischen Botschaft in Beijing. [Norw3:norw2] Bock, Carl Alfred (Kopenhagen 1849-1932 Oslo) : Norwegischer Naturforscher, Entdeckungsreisnder, Diplomat Biographie 1886-1893 Carl Alfred Bock ist Vizekonsul des schwedisch-norwegischen Generalkonsulats in Shanghai. [Wil] 1893-1902 Carl Alfred Bock ist Generalkonsul des schwedisch-norwegischen Generalkonsulats in Shanghai. [Wik] Bugge, Sten = Bugge, Joseph Laurentius Sten (Adal 1885-1977) : Norwegischer Missionar Biographie 1910-1934 Sten Bugge ist als Missionar in China, arbeitet für den YMCA (Young Men's Christian Association) in Hankou, Changsha und Taohualun (Hunan). 1928-1934 ist er Lehrer des Lutheran Seminary in Shekou (Hankou). [Bug1] Report Title - p. 2 of 11 Bibliographie : Autor 1915 Bugge, Sten. Fra det unge Kina. (Kristiania : Bjørnstad, 1915). [Aus dem jungen China]. -

The Hong Kong Baptist University (HKBU) Is a Regional

The Archives on the History of Christianity in China at Hong Kong Baptist University Library: Its Development, Significance, and Future Kylie Chan he Hong Kong Baptist University (HKBU) is a regional and mass education.”3 In addition, women missionaries made Tpioneer in establishing a valuable archives collection on important contributions as educators, role models, and social the history of Christianity in China, with the aim of preserving service workers. various facets of the Christian heritage in China.1 Archival materials on Christianity in China help to shed light on the anti-Christian movements in the 1920s that were Archives on the History of Christianity in China supported by political parties hoping to raise their political profile. Some recently surfaced publications on the Chinese The Archives on the History of Christianity in China (AHC) churches under the People’s Republic of China will allow more collection, consisting mainly of materials in either English or understanding of official churches, that is, the Catholic Patriotic Chinese, covers topics of Chinese Christians, missionaries, church Association and the Three-Self Movement, as well as of their history, and the history of Christianity in China. The archives counterparts among the underground churches. emphasizes the period before 1950. At the end of 2003, there were 3,084 volumes of monographs (2,078 in English and 1,006 in Development and Mission of the Archives Chinese), and 31,000 microform items, with thirty linear feet of archival records on the history of Christianity in China. Although Christianity first spread into China over 1,300 years The archives contains over 200 biographies and memoirs ago, formal research on the history of Chinese Christianity did detailing prominent missionaries, such as Hudson Taylor, James not begin before the 1930s and the 1940s.4 From 1949 to 1976 Outram Fraser, Karl Ludvig Reichelt, David Abeel, and John missionary activities in China were considered to be associated Leighton Stuart.