Neo-Liberalism in Japan's Tuna Fisheries?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DIJ-Mono 63 Utomo.Book

Monographien Herausgegeben vom Deutschen Institut für Japanstudien Band 63, 2019 Franziska Utomo Tokyos Aufstieg zur Gourmet-Weltstadt Eine kulturhistorische Analyse Monographien aus dem Deutschen Institut für Japanstudien Band 63 2019 Monographien Band 63 Herausgegeben vom Deutschen Institut für Japanstudien der Max Weber Stiftung – Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland Direktor: Prof. Dr. Franz Waldenberger Anschrift: Jochi Kioizaka Bldg. 2F 7-1, Kioicho Chiyoda-ku Tokyo 102-0094, Japan Tel.: (03) 3222-5077 Fax: (03) 3222-5420 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://www.dijtokyo.org Umschlagbild: Quelle: Franziska Utomo, 2010. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Dissertation der Universität Halle-Wittenberg, 2018 ISBN 978-3-86205-051-2 © IUDICIUM Verlag GmbH München 2019 Alle Rechte vorbehalten Druck: Totem, Inowrocław ISBN 978-3-86205-051-2 www.iudicium.de Inhaltsverzeichnis INHALTSVERZEICHNIS DANKSAGUNG . 7 SUMMARY: GOURMET CULTURE IN JAPAN – A NATION OF GOURMETS AND FOODIES. 8 1EINLEITUNG . 13 1.1 Forschungsfrage und Forschungsstand . 16 1.1.1 Forschungsfrage . 16 1.1.2 Forschungsstand . 20 1.1.2.1. Deutsch- und englischsprachige Literatur . 20 1.1.2.2. Japanischsprachige Literatur. 22 1.2 Methode und Quellen . 25 1.3 Aufbau der Arbeit . 27 2GOURMETKULTUR – EINE THEORETISCHE ANNÄHERUNG. 30 2.1 Von Gastronomen, Gourmets und Foodies – eine Begriffs- geschichte. 34 2.2 Die Distinktion . 39 2.3 Die Inszenierung: Verstand, Ästhetik und Ritual . 42 2.4 Die Reflexion: Profession, Institution und Spezialisierung . 47 2.5 Der kulinarische Rahmen . 54 3DER GOURMETDISKURS DER EDOZEIT: GRUNDLAGEN WERDEN GELEGT . -

Spring Summer Autumn Winter

Rent-A-Car und Kagoshi area aro ma airpo Recommended Seasonal Events The rt 092-282-1200 099-261-6706 Kokura Kokura-Higashi I.C. Private Taxi Hakata A wide array of tour courses to choose from. Spring Summer Dazaifu I.C. Jumbo taxi caters to a group of up to maximum 9 passengers available. Shin-Tosu Usa I.C. Tosu Jct. Hatsu-uma Festival Saga-Yamato Hiji Jct. Enquiries Kagoshima Taxi Association 099-222-3255 Spider Fight I.C. Oita The Sunday after the 18th day of the Third Sunday of Jun first month of the lunar calendar Kurume I.C. Kagoshima Jingu (Kirishima City) Kajiki Welfare Centre (Aira City) Spider Fight Sasebo Saga Port I.C. Sightseeing Bus Ryoma Honeymoon Walk Kirishima International Music Festival Mid-Mar Saiki I.C. Hatsu-uma Festival Late Jul Early Aug Makizono / Hayato / Miyama Conseru (Kirishima City) Tokyo Kagoshima Kirishima (Kirishima City) Osaka (Itami) Kagoshima Kumamoto Kumamoto I.C. Kirishima Sightseeing Bus Tenson Korin Kirishima Nagasaki Seoul Kagoshima Festival Nagasaki I.C. The “Kirishima Sightseeing Bus” tours Late Mar Early Apr Late Aug Shanghai Kagoshima Nobeoka I.C. Routes Nobeoka Jct. M O the significant sights of Kirishima City Tadamoto Park (Isa City) (Kirishima City) Taipei Kagoshima Shinyatsushiro from key trans portation hubs. Yatsushiro Jct. Fuji Matsuri Hong Kong Kagoshima Kokubu Station (Start 9:00) Kagoshima Airport The bus is decorated with a compelling Fruit Picking Kirishima International Tanoura I.C. (Start 10:20) design that depicts the natural surroundings (Japanese Wisteria Festival) Music Festival Mid-Apr Early May Fuji (Japanese Wisteria) Grape / Pear harvesting (Kirishima City); Ashikita I.C. -

Feelin' Casual! Feelin' Casual!

Feelin’ casual! Feelin’ casual! to SENDAI to YAMAGATA NIIGATA Very close to Aizukougen Mt. Chausu NIIGATA TOKYO . Very convenient I.C. Tohoku Expressway Only 50minutes by to NIKKO and Nasu Nasu FUKUSHIMA other locations... I.C. SHINKANSEN. JR Tohoku Line(Utsunomiya Line) Banetsu Utsunomiya is Kuroiso Expressway FUKUSHIMA AIR PORT Yunishigawa KORIYAMA your gateway to Tochigi JCT. Yagan tetsudo Line Shiobara Nasu Nishinasuno- shiobara shiobara I.C. Nishi- nasuno Tohoku Shinkansen- Kawaji Kurobane TOBU Utsunomiya Line Okukinu Kawamata 3 UTSUNO- UTSUNOMIYA MIYA I.C. Whole line opening Mt. Nantai Kinugawa Jyoutsu Shinkansen Line to traffic schedule in March,2011 Nikko KANUMA Tobu Bato I.C. Utsunomiya UTSUNOMIYA 2 to NAGANO TOCHIGI Line TOCHIGI Imaichi TSUGA Tohoku Shinkansen Line TAKA- JCT. MIBU USTUNOMIYA 6 SAKI KAMINOKAWA 1 Nagono JCT. IWAFUNE I.C. 1 Utsunomiya → Nikko JCT. Kitakanto I.C. Karasu Shinkansen Expressway yama Line HITACHI Ashio NAKAMINATO JR Nikko Line Utsunomiya Tohoku Shinkansen- I.C. I.C. TAKASAKI SHIN- Utsunomiya Line TOCHIGI Kanuma Utsunomiya Tobu Nikko Line IBARAKI AIR PORT Tobu Motegi KAWAGUCHI Nikko, where both Japanese and international travelers visit, is Utsuno- 5 JCT. miya MISATO OMIYA an international sightseeing spot with many exciting spots to TOCHIGI I.C. see. From Utsunomiya, you can enjoy passing through Cherry Tokyo blossom tunnels or a row of cedar trees on Nikko Highway. Utsunomiya Mashiko Tochigi Kaminokawa NERIMA Metropolitan Mibu I.C. Moka I.C. Expressway Tsuga I.C. SAPPORO JCT. Moka Kitakanto Expressway UENO Nishikiryu I.C. ASAKUSA JR Ryomo Line Tochigi TOKYO Iwafune I.C. Kasama 2 Utsunomiya → Kinugawa Kitakanto Expressway JCT. -

FOODEX JAPAN Secretariat ■During the Show(March 7~10, 2017) ■After the Show(From March 14, 2017 Onwards) Makuhari Messe, Hall 3・6 Secretariat Office

Next Show MAP & EVENT 2018 3,250 Exhibitors from 79 countries & regions! March (Tue) - (Fri), Makuhari Messe Japan 10:00-17:00(16:306 close on last9 day) March 7(Tue) -10 (Fri), 2017 10:00-17:00(16:30 close on last day) Makuhari Messe Hall 1-10, Japan teway to A Ga sia he n t M , a n r a k p e a t J s ts J e ap k a ar n, M the ian Gateway to As Attention!! for next show exhibitors, You will have next year information at the secretariat office in Hall 6,10. For Inquiries FOODEX JAPAN Secretariat ■During the show(March 7~10, 2017) ■After the show(from March 14, 2017 onwards) Makuhari Messe, Hall 3・6 Secretariat office. c/o Japan Management Association 2-1 Nakase, Mihama-ku, Chiba-city, Chiba, 261-8550 Japan 1-2-2 HITOTSUBASHI CHIYODA-KU,Tokyo 100-0003 Sumitomo Corporation Takebashi Bldg. 14F Makuhari Messe, Hall 10 Secretariat office. Tel : +81-3-3434-1391 Fax : +81-3-3434-8076 2-2-1 Nakase, Mihama-ku, Chiba-city, Chiba, 261-8550 Japan E-mail: [email protected] Concurrent Event Hall 11 *Our office will move to Shibakoen, Minato-ku from 2017/ January, 2018. (Scheduled) Please check the details in the official website. URL : http://www.jma.or.jp 3/7(Tue) Individual transactions between The Organizer will not be held responsible for the content of individual transactions, negotiations and ~ (Fri) Exhibitors and Visitors contracts between Exhibitors and Visitors. Individual transactions are to be carried out at your own risk. -

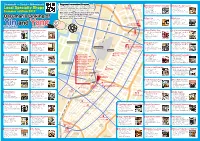

Fuji-Kawaguchiko Gourmet Guide

te it! A gre Tas at view a nd un ique foo d o ji-Kaw nl Fu ag y h uc er 湖 グルメガイド h e! 士河口 ik 富 Gou o rme 2020~2021 t G ui de ✿ Contents Japanese food How to read this guide ………………………2 QRcode Have a good food and Scan the QR code, HOTO&UDON Shop names you can get a location experience at (Local style noodles) information on smart Shop No phones. Fuji-Kawaguchiko! ………………………7 (Korean BBQ) YAKINIKU Map code Welcome to Fujikawaguchiko Town. Located This code is on a plateau in the north of Mt. Fuji, at an Chinesefood, corresponded maps altitude of 800 m, Fujikawaguchiko Town Asian food from page 30 to 3rd Recommendations is surrounded by rich nature with four cover. ……………………… lakes: Lake Kawaguchiko, Lake Saiko, Lake 12 Shojiko, and Lake Motosuko. You can enjoy magnificent views of Mt. Fuji from any Western style food, Introduction from location in Fujikawaguchiko town. In addition, shops there are many impressive sights, including a Italian,French number of world heritage sights. ………………………15 Enjoying the delicious cuisine in Fujikawaguchiko Town is essential for your Cafe trip. A variety of dishes, served in distinctive ………………………20 Phone number Address Opening hours shops, will surely make your journey memorable. Non-working day Number of seats Number of parking lots Why don’t you go out in the city with this Japanese pub,bar gourmet guide and experience the unique ………………………26 food culture that you can only enjoy in No smoking Separation of smoking Smoking allowed Fujikawaguchiko Town. Shop index………28 Maps………30 Take-away available Kids welcome Credit card available ✿ Column Transport service Wheelchair accesible Private room Tradition of eating horsemeat…6 Flour food culture Western style table Foreigners welcome Free WiFi in Fujikawaguchiko Town…11 Saiko Iyashi no Sato Nemba…14 ✿ Attention Agricultural direct sale “Oishi-ya”…19 Please note that when you call the telephone Contents of this booklet is based on information numbers of the facilities listed in the magazine, Local sake and beer using wonderful water from shops. -

OFFICIAL GAZETTE GOVERNMENT PRINTING ABENCY | Engl/SH E^T/QN B2H14-^-F-Fl =+ B M^.MM@M*£St

OFFICIAL GAZETTE GOVERNMENT PRINTING ABENCY | ENgL/SH E^T/QN B2H14-^-f-fl =+ B m^.MM@m*£st No. 1081 FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 4, 1949 Price 28,00 yen In Article 3, "and the Postal Services Special LAW Account" shall be added next to "the General Account". - I hereby promulgate the Law for Partial Amend- ments to the Law concerning the Payment of Article 3. The Postal Services Special Account Law Revenues by means of Stamps, etc. (Law No. 109 of 1949) shall be partially amended as follows : Signed : HIROHITO, Seal of the Emperor In Article 40, "The proceeds less the amount of This fourth day of the eleventh month of the the purchasing and the expenses necessary for the twenty-fourth year of Showa (November 4, 1949) sales of the revenue stamps shall be transferred to Prime Minister the General Account." shall be amended as "Out of YOSHIDA Shigeru the proceeds from sales minus the expenses for Law No. 222 re-purchase and the expenses necessary for the sales of stamps, the amount concerning revenue Law for Partial Amendments to the Law stamps and transaction tax stamps shall be trans- concerning the Payment of Revenues ferred to the General Account and the amount by means of Stamps, etc. concerning the unemployment insurance stamps Article 1. The*Law concerning the Payment of shall be transferred to the Unemployment Insurance Revenues by means of Stamps (Law No. 142 of Special Account." 1948) shall be partially amended as follows : Article 4. The Welfare Insurance Special Account In Article 1, "Article 61 of the Juvenile Law Law (Law No. -

“Unzen, Sparkling with Seasonal Delights and Dreams for the Future”

“Unzen, sparkling with seasonal delights and dreams for the fut Welcome to a trip like no other Tourism and Products Division, Industry Promotion Department, Unzen City Office 714 Azumacho Ushiguchimyo, Unzen City, Nagasaki 859-1107, Japan TEL 0957-38-3111 FAX 0957-38-3205 Unzen Tourist Association 320 Obamacho Unzen, Unzen City, Nagasaki 854-0621, Japan TEL 0957-73-3434 FAX 0957-73-2261 Obama Hot Spring Tourism Association 14-39 Obamacho Kitahonmachi, Unzen City, Nagasaki 854-0514 Japan TEL 0957-74-2672 FAX 0957-74-2884 Mount Unzen Visitor Center 320 Obamacho Unzen, Unzen City, Nagasaki 854-0621 Japan TEL 0957-73-3636 FAX 0957-73-2136 -Unzen City Slogan Lots of downloadable content! For more information Unzen City Search ure” Created October 2014 Unzen City Tourism Guide Heisei Shinzan Unzen Jigoku Nature Model routes By area Number ones/only ones Unzen Fugendake Hiking Trail Map Volcanoes, their blessings, Welcome to the and a rich natural environment Unzen Volcanic Area Geopark world-renowned Specialties What is a geopark? What are the Unzen Volcanic Area Geopark Geoparks are outdoor “museums” highlights of Unzen City? where visitors can learn about the Earth’s history. Geoparks Geosites (places where visitors Shimabara Peninsula can observe and experience became the first demonstrate not only interesting unique topography and geological topography and geological formations, formations) such as Heisei Shinzan Dining/shopping Japanese member but also examples of human lifestyles and Chijiwa Fault. Unzen also offers and histories shaped by its natural two completely different hot spring of the Global Geoparks (Onsen) water qualities at its two spas, features. -

Lobsters, Hot Air Balloons, and the Hometown Tax: a Japanese Model for Revitalizing Rural Economies in the United States

KANZAWA – FINAL LOBSTERS, HOT AIR BALLOONS, AND THE HOMETOWN TAX: A JAPANESE MODEL FOR REVITALIZING RURAL ECONOMIES IN THE UNITED STATES Janet W. Kanzawa* Many municipalities in the United States are short of the tax revenue they need and have had to cut spending on public goods, which has lowered the quality of life for their residents. Municipalities in Japan face the same problem. Japan has developed an effective method for raising tax revenue for local governments and revitalizing languishing economies. Japan’s “Hometown Tax” system empowers taxpayers to divert tax revenue from affluent urban governments to struggling rural governments, stimulates small businesses and enables rural governments to be more autonomous and financially independent. Under the Hometown Tax, a taxpayer that makes a charitable contribution to a local government receives a tax deduction and credit amounting to almost the entire value of the charitable contribution. At almost no extra cost, the taxpayer can select a Return Gift to receive from a local business in the region. Return Gifts range from deliveries of fresh locally-caught lobsters to vouchers for hot air balloon rides, and are listed on online portals that connect taxpayers to municipal and prefectural governments throughout Japan. The online portals have also become donation channels for regions experiencing natural disasters. * J.D. Candidate 2018, Columbia Law School; B.A. 2014, Vassar College. The author would like to thank Professor David Schizer for his invaluable guidance and feedback. She would also like to thank Jen Barrows and Geoffrey Litt for their helpful comments, Yukino Nakashima and the Toshiba Library for Japanese Legal Research, and the outstanding editorial staff of the Columbia Business Law Review for their assistance in preparing this Note for publication. -

Ideals Versus Realities in the Japanese Periphery - the Case of Endogenous Development

Ideals versus Realities in the Japanese Periphery - The Case of Endogenous Development SAM K. STEFFENSEN Endogenous development in Japan goes back to the prewar period, but is it correct to say that it firmly took root in society when we entered the 1970s expressed by words such as "locality making" (machi zulcuri) and "village awakening" (mura olcoshi). Endogenous development started out as an alternative approach among regions which were being left behind during the high economic growth period or affected by its failures. The most celebrated examples are probably Ikeda town in Hokkaido prefecture, and Yufuin and Oyama towns in Oita prefecture.1 Endogenous Development as Ideal The idea of local "development from within" (naihatsutelci hatten) became a challenging issue in Japanese regional development debates of the 1970s. From the outset it was contextually connected to progressive city government initiatives, regionalist theories, and novel revitalization activities in structurally backward l~calities.~ Furthermore, it gained ideological momentum from the reformed discussions on development theories taking place in the United Nations during that period.3 AS a matter of course, when the Dag Hammarskjold Foundation in 1975 applied the term "endogenous development" in a report, it gradually became accepted as a proper translation of the Japanese naihatsutelci hatten concept.4 As indicated above, to promote this notion in Japan the relatively successful pioneering examples of Ikeda, Yufuin, Oyama, including a few other localities, were always right at hand. Ikeda and Oyama town started their individual revitalization strategies in the early 1960s as a response to rural decline and poverty. Yufuin embarked on its city- 54 The Copenhagen Journal of Asian Studies 9 94 Ideals versus Realities in the Japanese Periphery making strategy in the early 1970s mainly as an reaction against externally imposed development projects and spreading real estate speculations. -

ICT, Robotics and Biobased Economy

ICT, Robotics and Biobased Economy Agricultural Innovations in Japan Market Report 2017 Department of Agriculture | Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands 3-6-3 Shibakoen | Minato-ku | Tokyo | 105-0011 ICT, Robotics and Biobased Economy Agricultural Innovations in Japan Summary 1. Use and application of big data and ICT in agricultural marketing; 2. Sensors, GPS, robotic technology, IoT, and connectivity; 3. Food innovation (hub): The roles of governments and public institutions; 4. SWOT analysis for innovation in the food industry; 5. Market entry by businesses (trends in Fujitsu and Hitachi as well as Mitsubishi and other trading firms): Relations with JA (Agricultural Cooperative Associations); 6. Opportunities for foreign businesses and knowledge/research organizations to form alliances; Agricultural innovation programs led by foreign businesses, examples of projects in which Japan invests, those of joint research and development with foreign partner companies and associations, and the like. This publication and its content is copyright of The Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, Tokyo. Any redistribution or reproduction of part or all of the contents in any form is prohibited other than the following: - you may print or download to a local hard disk extracts for your personal and non-commercial use only; - you may copy the content to individual third parties for their personal use, but only if you acknowledge the publication as the source of the material. Copyright © The Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands 2018 All rights reserved. agroberichtenbuitenland.nl/landeninformatie/japan 1 ICT, Robotics and Biobased Economy Agricultural Innovations in Japan Table of Contents Summary ................................................................................................................. 1 1 Present condition of and challenges for agriculture in Japan ............................. -

Yin and Yang Yin and Yang

Shinbashi ~ Ginza ~ Nihonbashi Regional Innovation Project 43 22 Ishikawa Hyakumangoku Monogatari 33 Hokkaido Foodist Yaesu-ten This shopping guide leaflet is made to support Nihonbashi Edo Honten B1 Yaesu shopping mall regional revitalization through linking the local Fukushima-kan Local Specialty Shops TH Ginza Bldg MIDETTE 2-2-1 Yaesu Mie Terrace specialties and tourists visiting to Tokyo. 42 2-2-18 Ginza TEL: 03-3275-0770 Summer edition 2017 TEL: 03-6228-7177 http://www.foodist.co.jp/ Daruman’s Five Elements of Yin and Yang http://100mangokushop.jp/ Ⓒsantohsha http://www.daruman.info/ Santosha, Co., Ltd Regional Innovation Project Team Otemachi Sta. Daruman's Linking of Otemachi Sta. Mitsukoshi-mae Sta. TEL: 03-3231-7739 http://santho.net/ Bank of Japan 23 Zarai Oita 34 Kyoto-kan Nihonbashi Otemachi Sta. Shimane-kan 8F Hulic Nishiginza Bldg 1F Yanmar Tokyo Bldg 2-2-2 Ginza 2-1-1 Yaesu 41 Wood TEL: 03-3563-0322 TEL: 03-5204-2260 Water Bridge Niigata 40 http://www.zarai.jp http://www.kyotokan.jp/ Yin and Yang Nara Mahoroba-kan Tokyo Metro Hanzomon Line local regions metropolis 39 Metal Fire Tokyo Metro Chiyoda Line Chiyoda Metro Tokyo 38 1 Kagawa & Ehime Setouchi Shunsai-kan 109 秋田ふるさと館Akita Furusato-kan 24 Ginza Washita Shop 35 Fuji no Kuni Yamanashi-kan 1-2F Shinbashi Marine Bldg 有楽町2-10-11F Tokyo Traffic Hall 1F,B1F Maruito Ginza Bldg 1F Nihonbashi Plaza Bldg Earth 2-19-10 Shinbashi 東京交通会館1F2-10-1 Yurakucho 1-3-9 Ginza 2-3-4 Nihonbashi Nihonbashi Nihonbashi TEL: 03-3574-2028 03-3214-2670TEL: 03-3214-2670 Mitsukoshi TEL: 03-3535-6991 TEL: 03-3241-3776 Tokyo Metro TozaiToyama Line -kan http://www.setouchi- http://www.a-bussan.jp/ Line Marunouchi Metro Tokyo http://www.washita. -

As of 26Th, August 2020) *Items Listed May Be Modified Along with the Circumstances of Supervising Organizations

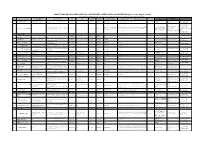

ADDITIONAL ENGLISH INFORMATION OF EXCELLENT SUPERVISING ORGANIZATION (As of 26th, August 2020) *Items listed may be modified along with the circumstances of supervising organizations. In that case, we will modify the list shortly. No. of Name of Organization Date of Approval Date of Expiry Accepting Country Job Categories (Eligible when Interns shifts to Technical Person in charge No. Name of Organization Address in English TEL HP Implementing TEL (in English) (Y/M/D) (Y/M/D) *Refer to Country Code Intern Training (ii)) *Refer to Category Code Name Email Organizations* FAX ISS HOKKAIDO business 〒067-0056, 2F No.225 Mihara, Ebetsu-shi, TEL: 011-807-0491 1 ISS北海道事業協同組合 0118070491 N/A 2018/10/31 2023/10/30 CHN, VNM 1-1, 1-2, 3-21, 4-2, 4-9, 4-10, 6-14, 7-6 70 佐藤 (Sato) [email protected] cooperative association Hokkaido FAX: 011-807-0492 アシストワン札幌オフィス TEL: 011-200-8700 [email protected] 1-1, 1-2, 3-1, 3-2, 3-3, 3-4, 3-5, 3-6, 3-7, 3-8, 3-10, 3-12, 3-13, 諏訪 (SUWA)(日本国内) FAX: 011-200-8600 〒080-0301, 14-1-15 Kino Odori nishi, Otofuke- CHN, IDN, KHM, MMR, MNG, ootani@assistone- 2 アシストワンパートナーズ協同組合 0155435011 2020/5/13 2025/5/12 3-14, 3-15, 3-16, 3-17, 3-18, 3-19, 3-20, 3-21, 4-3, 4-4, 4-9, 6- 1 大谷 (OTANI)(日本国内) アシストワンパートナーズ協 cho, Kato-gun, Hokkaido PHL, THA, VNM group.com 1, 6-6, 6-7, 7-3, 7-4, 7-6, 7-7, 7-11, 7-12, 7-13 伊藤 (ITOU)(日本国内) 同組合 [email protected] TEL: 0155-43-5011 FAX: 0155-30-7111 3 網走国際交流協同組合 0152462447 2018/12/10 2023/12/9 CHN 1-2, 4-2, 4-4, 4-6 7 アパレルファッション研究協同組合 4 0139551525 2018/1/22 2023/1/21 KHM 5-6 4 (事業休止中) 〒058-0204,