Mascots on the Loose: the Pragmatics of Kawaii (Cute)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mariko Mori and the Globalization of Japanese “Cute”Culture

《藝術學研究》 2015 年 6 月,第十六期,頁 131-168 Mariko Mori and the Globalization of Japanese “Cute” Culture: Art and Pop Culture in the 1990s SooJin Lee Abstract This essay offers a cultural-historical exploration of the significance of the Japanese artist Mariko Mori (b. 1967) and her emergence as an international art star in the 1990s. After her New York gallery debut show in 1995, in which she exhibited what would later become known as her Made in Japan series— billboard-sized color photographs of herself striking poses in various “cute,” video-game avatar-like futuristic costumes—Mori quickly rose to stardom and became the poster child for a globalizing Japan at the end of the twentieth century. I argue that her Made in Japan series was created (in Japan) and received (in the Western-dominated art world) at a very specific moment in history, when contemporary Japanese art and popular culture had just begun to rise to international attention as emblematic and constitutive of Japan’s soft power. While most of the major writings on the series were published in the late 1990s, problematically the Western part of this criticism reveals a nascent and quite uneven understanding of the contemporary Japanese cultural references that Mori was making and using. I will examine this reception, and offer a counter-interpretation, analyzing the relationship between Mori’s Made in Japan photographs and Japanese pop culture, particularly by discussing the Japanese mass cultural aesthetic of kawaii (“cute”) in Mori’s art and persona. In so doing, I proffer an analogy between Mori and popular Japanimation characters, SooJin Lee received her PhD in Art History from the University of Illinois-Chicago and was a lecturer at the School of Art Institute of Chicago. -

East-West Film Journal, Volume 3, No. 2

EAST-WEST FILM JOURNAL VOLUME 3 . NUMBER 2 Kurosawa's Ran: Reception and Interpretation I ANN THOMPSON Kagemusha and the Chushingura Motif JOSEPH S. CHANG Inspiring Images: The Influence of the Japanese Cinema on the Writings of Kazuo Ishiguro 39 GREGORY MASON Video Mom: Reflections on a Cultural Obsession 53 MARGARET MORSE Questions of Female Subjectivity, Patriarchy, and Family: Perceptions of Three Indian Women Film Directors 74 WIMAL DISSANAYAKE One Single Blend: A Conversation with Satyajit Ray SURANJAN GANGULY Hollywood and the Rise of Suburbia WILLIAM ROTHMAN JUNE 1989 The East- West Center is a public, nonprofit educational institution with an international board of governors. Some 2,000 research fellows, grad uate students, and professionals in business and government each year work with the Center's international staff in cooperative study, training, and research. They examine major issues related to population, resources and development, the environment, culture, and communication in Asia, the Pacific, and the United States. The Center was established in 1960 by the United States Congress, which provides principal funding. Support also comes from more than twenty Asian and Pacific governments, as well as private agencies and corporations. Kurosawa's Ran: Reception and Interpretation ANN THOMPSON AKIRA KUROSAWA'S Ran (literally, war, riot, or chaos) was chosen as the first film to be shown at the First Tokyo International Film Festival in June 1985, and it opened commercially in Japan to record-breaking busi ness the next day. The director did not attend the festivities associated with the premiere, however, and the reception given to the film by Japa nese critics and reporters, though positive, was described by a French critic who had been deeply involved in the project as having "something of the air of an official embalming" (Raison 1985, 9). -

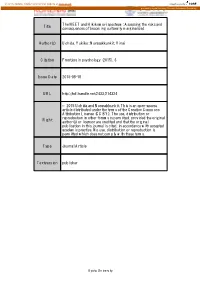

Title the NEET and Hikikomori Spectrum

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository The NEET and Hikikomori spectrum: Assessing the risks and Title consequences of becoming culturally marginalized. Author(s) Uchida, Yukiko; Norasakkunkit, Vinai Citation Frontiers in psychology (2015), 6 Issue Date 2015-08-18 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/214324 © 2015 Uchida and Norasakkunkit. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original Right author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms. Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 18 August 2015 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01117 The NEET and Hikikomori spectrum: Assessing the risks and consequences of becoming culturally marginalized Yukiko Uchida 1* and Vinai Norasakkunkit 2 1 Kokoro Research Center, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan, 2 Department of Psychology, Gonzaga University, Spokane, WA, USA An increasing number of young people are becoming socially and economically marginalized in Japan under economic stagnation and pressures to be more globally competitive in a post-industrial economy. The phenomena of NEET/Hikikomori (occupational/social withdrawal) have attracted global attention in recent years. Though the behavioral symptoms of NEET and Hikikomori can be differentiated, some commonalities in psychological features can be found. Specifically, we believe that both NEET and Hikikomori show psychological tendencies that deviate from those Edited by: Tuukka Hannu Ilmari Toivonen, governed by mainstream cultural attitudes, values, and behaviors, with the difference University of London, UK between NEET and Hikikomori being largely a matter of degree. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

Liste Des Jeux Nintendo NES Chase Bubble Bobble Part 2

Liste des jeux Nintendo NES Chase Bubble Bobble Part 2 Cabal International Cricket Color a Dinosaur Wayne's World Bandai Golf : Challenge Pebble Beach Nintendo World Championships 1990 Lode Runner Tecmo Cup : Football Game Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles : Tournament Fighters Tecmo Bowl The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle and Friends Metal Storm Cowboy Kid Archon - The Light And The Dark The Legend of Kage Championship Pool Remote Control Freedom Force Predator Town & Country Surf Designs : Thrilla's Surfari Kings of the Beach : Professional Beach Volleyball Ghoul School KickMaster Bad Dudes Dragon Ball : Le Secret du Dragon Cyber Stadium Series : Base Wars Urban Champion Dragon Warrior IV Bomberman King's Quest V The Three Stooges Bases Loaded 2: Second Season Overlord Rad Racer II The Bugs Bunny Birthday Blowout Joe & Mac Pro Sport Hockey Kid Niki : Radical Ninja Adventure Island II Soccer NFL Track & Field Star Voyager Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II : The Arcade Game Stack-Up Mappy-Land Gauntlet Silver Surfer Cybernoid - The Fighting Machine Wacky Races Circus Caper Code Name : Viper F-117A : Stealth Fighter Flintstones - The Surprise At Dinosaur Peak, The Back To The Future Dick Tracy Magic Johnson's Fast Break Tombs & Treasure Dynablaster Ultima : Quest of the Avatar Renegade Super Cars Videomation Super Spike V'Ball + Nintendo World Cup Dungeon Magic : Sword of the Elements Ultima : Exodus Baseball Stars II The Great Waldo Search Rollerball Dash Galaxy In The Alien Asylum Power Punch II Family Feud Magician Destination Earthstar Captain America and the Avengers Cyberball Karnov Amagon Widget Shooting Range Roger Clemens' MVP Baseball Bill Elliott's NASCAR Challenge Garry Kitchen's BattleTank Al Unser Jr. -

Kawaii Feeling in Tactile Material Perception

Kawaii Feeling in Tactile Material Perception Michiko Ohkura*, Shunta Osawa*, Tsuyoshi Komatsu** * College of Engineering, Shibaura Institute of Technology, {ohkura, l08021}@shibaura-it.ac.jp, ** Graduate School of Engineering, Shibaura Institute of Technology, [email protected] Abstract: In the 21st century, the importance of kansei (affective) values has been recognized. How- ever, since few studies have focused on kawaii as a kansei value, we are researching its physical at- tributes of artificial products. We previously performed experiments on kawaii shapes, colors, and sizes. We also performed experiments on kawaii feelings in material perception using virtual ob- jects with various visual textures and actual materials with various tactile textures. This article de- scribes the results of our new experiment on kawaii feeling in material perception using materials with various tactile textures corresponding with onomatopoeia, clarifying the phonic features of onomatopoeia with materials evaluated as kawaii. The obtained results are useful to make more at- tractive industrial products with material perception of kawaii feeling. Key words: kansei value, kawaii, tactile sensation, material perception, onomatopoeia 1. Introduction Recently, the kansei (affective) value has become crucial in industrials in Japan. The Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) determined that it is the fourth most important characteristic of industrial products after function, reliability, and cost [1]. According to METI, it is important not only to offer new functions and competitive prices but also to create a new value to strengthen Japan’s industrial competitiveness. Focusing on kansei as a new value axis, METI launched the “Kansei Value Creation Initiative” in 2007 [1,2] and held a kansei value creation fair called the “Kansei-Japan Design Exhibition” at Les Arts Decoratifs (Museum of Decora- tive Arts) at the Palais du Louvre in Paris in December 2008. -

SHINTŌ: EL CAMINO DEL CORAZÓN ‘Conciencia Mítica En El Japón Contemporáneo’

UNIVERSIDAD DE CHILE Facultad de Filosofía y Humanidades Departamento de Ciencias Históricas SHINTŌ: EL CAMINO DEL CORAZÓN ‘Conciencia Mítica en el Japón Contemporáneo’ Informe de Seminario de Grado: Mito, Religión y Cultura para optar al grado de Licenciada en Historia : ISABEL MARGARITA CABAÑA ROJAS PROFESOR GUÍA: JAIME MORENO GARRIDO Santiago, Chile 2008 AGRADECIMIENTOS . 4 I.-INTRODUCCIÓN . 5 Marco Teórico . 6 II.-DESARROLLO . 12 1. Conciencia Mítica y Shintō. 12 a) Conciencia Mítica según Georges Gusdorf . 12 b) Características Generales del Shintō . 14 c) Shintō y Mito . 18 2. Período Pre-Meiji . 24 a) Japón, Cultura agrícola . 24 b) Cultura China y Budismo . 27 c) Contactos con Occidente . 30 3. Período Post-Meiji . 32 a) La Apertura Económica . 33 b) El Shintō Estatal . 34 c) Después de 1945 . 36 III. CONCLUSIONES . 41 BIBLIOGRAFÍA . 43 LIBROS . 43 ARTÍCULOS . 44 ANEXO 1: MAPAS . 46 ANEXO 2: EJEMPLOS DE MATSURI . 48 ANEXO 3 : SANTUARIO DE ISE . 50 ANEXO 4 : JŌMON . 52 ANEXO 5 : KOFUN . 55 ANEXO 6 :KAN-NAME-SAI . 57 ANEXO 7 :HŌNEN MATSURI . 58 SHINTŌ: EL CAMINO DEL CORAZÓN AGRADECIMIENTOS En primer lugar, quisiera agradecer a mis padres, Carlos y María Elena. El tema de este informe llegó a mí muy similar a una epifanía. El marco general estaba, pero no podía encontrar aquello que hiciera sentido en mí como esperaba que sucediera, hasta que vi en el Mito lo que faltaba al rompecabezas. La libertad que sentí de poder darme el tiempo de buscar lo que anhelaba como objeto de estudio, de haber podido estudiar lo que quería, y de cultivar esta inquietud que ya me acompaña desde hace diez años, y que con paciencia entendieron, se los debo a ellos. -

The Literature of Kita Morio DISSERTATION Presented In

Insignificance Given Meaning: The Literature of Kita Morio DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Masako Inamoto Graduate Program in East Asian Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Professor Richard Edgar Torrance Professor Naomi Fukumori Professor Shelley Fenno Quinn Copyright by Masako Inamoto 2010 Abstract Kita Morio (1927-), also known as his literary persona Dokutoru Manbô, is one of the most popular and prolific postwar writers in Japan. He is also one of the few Japanese writers who have simultaneously and successfully produced humorous, comical fiction and essays as well as serious literary works. He has worked in a variety of genres. For example, The House of Nire (Nireke no hitobito), his most prominent work, is a long family saga informed by history and Dr. Manbô at Sea (Dokutoru Manbô kôkaiki) is a humorous travelogue. He has also produced in other genres such as children‟s stories and science fiction. This study provides an introduction to Kita Morio‟s fiction and essays, in particular, his versatile writing styles. Also, through the examination of Kita‟s representative works in each genre, the study examines some overarching traits in his writing. For this reason, I have approached his large body of works by according a chapter to each genre. Chapter one provides a biographical overview of Kita Morio‟s life up to the present. The chapter also gives a brief biographical sketch of Kita‟s father, Saitô Mokichi (1882-1953), who is one of the most prominent tanka poets in modern times. -

Bloomsbury Children's Catalog Fall 2020

BLOOMSBURY FALL 2020 SEPTEMBER DECEMBER BLOOMSBURY CHILDREN'S BOOKS • SEPTEMBER 2020 JUVENILE FICTION / ANIMALS / BEARS OLIVIA A. COLE Time to Roar Sometimes you must ROAR. This powerful picture book shows the importance of raising your own strong voice to defend what you love. Sasha the bear loves the meadow in her forest more than anything. But when great, yellow machines threaten to cut and burn the forest, Sasha and the other animals must determine the best way to stop them. “Don’t go roaring,” Squirrel tells Sasha. Bird tries singing to SEPTEMBER the machines sweetly. Rabbit thumps her foot at them. Deer Bloomsbury Children's Books tries running and leading them away. None of these methods Juvenile Fiction / Animals / Bears work—must they flee? The animals need something louder, On Sale 9/1/2020 Ages 3 to 6 something bigger, something more powerful. Sasha knows Hardcover Picture Book 32 pages her voice—her roar—is the most powerful tool she has. 9.6 in H | 10.8 in W Because sometimes you must roar. Carton Quantity: 0 This picture book is the perfect introduction to showing ISBN: 9781547603701 $17.99 / $24.50 Can. young readers the power of their own voices—to stand up for what they believe in, to protect what they love, and to make a change in the world. Olivia Cole is an author and blogger from Louisville, KY. She is the author of a New Adult series and a young adult series, and her essays have been published at Real Simple, the LA Times, HuffPost, Teen Vogue, and others. -

The Rise of Nationalism in Millennial Japan

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2010 Politics Shifts Right: The Rise of Nationalism in Millennial Japan Jordan Dickson College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Dickson, Jordan, "Politics Shifts Right: The Rise of Nationalism in Millennial Japan" (2010). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 752. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/752 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Politics Shifts Right: The Rise of Nationalism in Millennial Japan A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelors of Arts in Global Studies from The College of William and Mary by Jordan Dickson Accepted for High Honors Professor Rachel DiNitto, Director Professor Hiroshi Kitamura Professor Eric Han 1 Introduction In the 1990s, Japan experienced a series of devastating internal political, economic and social problems that changed the landscape irrevocably. A sense of national panic and crisis was ignited in 1995 when Japan experienced the Great Hanshin earthquake and the Aum Shinrikyō attack, the notorious sarin gas attack in the Tokyo subway. These disasters came on the heels of economic collapse, and the nation seemed to be falling into a downward spiral. The Japanese lamented the decline of traditional values, social hegemony, political awareness and engagement. -

Page 1 H a N N a H P a R K T R a F F I C L I G H T S

T R A F F I C L I G H T S A G U I D E S T U D I O P R O J E C T // S Y T E M S T U D I O P R J E C // H A N N A H P A R K a n o v e r v i e w K E Y T E R M S - traffic lights - traffic signals - traffic lamps - traffic semaphore - signal lights - stop lights - intersections - pedestrians - lane control - face - pole mount - lenses - red // yellow // green Nowadays, the red, yellow, and green glow of traffic lights are found everywhere across the world. They are embedded so deeply into the foundation of cities and streets that drivers and pedestrians are usually unaware of its essential role in a complex traffic system. However, this ubiquitous invention comes with years of early prototypes and design refinements that are still worked on today. components // history THEN [1] NOW [2] traffic before signal lights [3] T R [4] A F F I [5] C [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] my photographs new york city [12] [13] new york city [14] [15] [16] around the world a s i a korea [17] korea [20] japan [18] japan [21] japan [19] geneva [22] copenhagen [23] brussels [24] e u r o p e berlin [25] prague [26] e u r o p e e u r o p e london [27] belfast [28] urtrecht [29] berlin [30] e u r o p e brussels [31] berlin [32] new york [33] new york [34] new york [35] n o r t h a m e r i c a additional NIGHT GLOW [38] [36] [37] [39] [40] [41] london art [43] traffic light design [42] CLASSIC YELLOW LIGHTS YELLOW CLASSIC [44] [45] [46] culture book 1 [47] book 2 [48] song [49] game [50] CITATIONS [1] U.S. -

PICTURES of the FLOATING WORLD an Exploration of the World of the Yoshiwara, 吉原

Cherry Blossom in the Yoshiwara by Yoshikazu PICTURES OF THE FLOATING WORLD An exploration of the world of the Yoshiwara, 吉原 PICTURES OF THE FLOATING WORLD In the nightless city Floating free from life’s cares Picture memories Haiku Keith Oram INTRODUCTION Japanese woodblock prints that recorded the Ukiyo, the ‘Floating World’ of the Yoshiwara of Edo city were so numerous that during the nineteenth century they were used to wrap ceramics exported to Europe. This practice provided some European artists with their first proper encounter with these beautifully created images. The impact on western art of their bold colours and sensuous line was quite significant influencing many artists of the avant gard. The story of those prints, however, began much earlier in the seventeenth century. First a little background history. The battle of Sekigahara in 1600 and the fall of Osaka in 1615 allowed Tokugawa Ieyasu to gain complete control of Japan. He had been made Shogun, supreme military leader, in 1603, but the fall of Osaka was the final action that gave him complete control. Almost his first act was to move the capital from Kyoto, the realm of the Emperor, to Edo, now Tokyo. This backwater town, now the new capital, grew very quickly into a large town. Tokugawa Iemitsu, Shogun 1623-51, required the daimyo of Japan, local rulers and warlords, to remain in Edo every other year, but when they returned to their fiefs he made them leave their families in the capital. This ‘hostage’ style management, sankin tokai, helped to maintain the peace. The other affect was that the daimyo needed to build large homes in Edo for their families.