Freedom to Learn: Basic Skills for Learners with Learning Difficulties And/Or Disabilities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Refresh of the Janet Network in the East Midlands Roll Out: Scheduled Virgin Media Connection Date Is 24Th September (I.E

REFRESH OF THE JANET NETWORK IN THE EAST MIDLANDS ROLL OUT: SCHEDULED VIRGIN MEDIA CONNECTION DATE IS 24TH SEPTEMBER (I.E. BY THAT DATE) UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED READY FOR SERVICE: FINAL MIGRATION WILL BE COMPLETED BY EMMAN IN AUTUMN 2013 NB: EVEN WHERE THE TELCO IS LATE DELIVERING, CONNECTIVITY WILL BE MAINTAINED THROUGH EXISTING CONNECTION. ACCESS CIRCUITS Status Status Status Status Status Status Status Customer "B" END Remote Sites "A" END University Band Circuit ID Post Code Supplier POP Sites Post Code Supplier width Bilborough College NG8 4DQ BT BT 100Mb 27/06 BT planning and survey 11/07 BT fibre work complete 01/08 BT FF & T to be 15/08.VM seeking 22/08 still awaiting 04/09 - telco delivery College Way. Openreach Openreach work complete. A to B end. confirmed 02/09/13 confirmation that the Derby confirmation that BT FF & complete Nottingham University of Nottingham cabinet is in place with T will be 02/09 Cripps CC. University NG7 2RD power so that the works Park Nottingham will go ahead as scheduled. 60 Bishop Grosseteste University LN1 3DY BT University of Lincoln LN6 7TS BT 1Gb As per contract - connection 11/07 BT fibre work complete 01/08 Final Fit and Test date 15/08 Final Fit and Test date As previous update 18/09 - BT amending College. Openreach Main Admin Building, Openreach not required until Dec 1 A to B end. TBA. TBA. presentation to mulimode Newport. Lincoln Brayford Pool. Lincoln 61 Boston College PE21 6JF BT University of Lincoln. LN6 7TS Virgin Media 200Mb 20/06 U of Lincoln end is VM - 25/07 ECD currently 02/09 01/08 - BT need to complete 15/08 BT awaiting access 22/08 BT access to Boston 18/09 - telco delivery Skirbeck Road. -

Under-16 Home to School Transport Policy and Post-16 Transport Policy

POST-16 TRANSPORT POLICY STATEMENT 2017/18 ACADEMIC YEAR NOTTINGHAMSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL POST-16 TRANSPORT POLICY STATEMENT – 2017/18 ACADEMIC YEAR 1. Summary of Policy Statement This statement informs learners and their parents/carers of the support for transport that is available to help them access post-16 learning opportunities. The Council has consulted with various stakeholders in preparing this document. The statement includes information from the Council and provides links to enable learners and their parents/carers to access the most up to date transport and travel information from schools, colleges of further education, transport providers and other relevant sources. The aim is to provide the most up to date information about how to get to school or college. The statement also explains the support available to learners with special educational needs and or learning/mobility difficulties and gives information about the Council’s scheme of independent travel training. 2. Post-16 Travel Assistance Scheme 2017/18 2.1 Who is eligible to join the scheme? To participate in the scheme a student must:- • be a Nottinghamshire County resident (excludes students resident in Nottingham City) • be attending a full time course (a minimum of 540 guided learning hours per year over a period of a least 30 weeks) at a school (including Academies), college of further education or Independent Specialist Provider that is funded directly by the Education Funding Agency (the scheme does not apply to fee paying independent schools, higher education courses or universities) • live more than three miles from the school/college using the nearest available walking route • be over compulsory school age but under 19 years of age on 1 September 2017 For entitlements and additional benefits that are available for students with a disability or special transport need, see parts 4-6 below . -

Education and Training Providers

Post Holbrook education opportunities Landmarks Specialist College - Chesterfield 01246 433788 Specialist Independent college for people with learning difficulties and disabilities. Their mission – To deliver high quality education and support that maximises life opportunities for our learners. T2 – Derby 01332 370978 At Transition2 we believe that all our alumni should move on from education into meaningful opportunities in adult life, through which they can continue to develop their skills as lifelong learners, as well as share their assets with the community as active citizens. Derby College – Broomfield 01332 387473 Derby College is a further education centre with sites located within Derbyshire. It delivers training in workplace locations across England. An extensive working estate, the campus supports the land based, leisure, sport and public services sectors, with Students on a variety of pathways leading to positive destinations in the world of work, further and higher education. Buxton & Leek College 0800 074 0099 Vocational course levels are BTEC’s, NVQ’s, Developing skills, Working towards Independence and Independence & Living Skills and Learning for Leisure. Entry level 1–3 for students who find learning difficult or who have become disengaged with education. You will be given the support you need in an all- inclusive learning environment. Level 1 – 3 and beyond also available. Portland College – Mansfield 01623 499111 A leading specialist college. Working with disabled people to develop their employability, independence and communication skills. With such a wide range of qualifications available - from pre-entry level to level 3, we will tailor a programme to suit your individual disability or needs. RNIB College – Loughborough 01509 611 077 RNIB College Loughborough supports a wide range of students to achieve their goals. -

Learning Technologist Award 2014

UNIVERSITY COSECTOR OF LONDON Learning Technologist of the Year Awards 1997–2016 The Association for Learning Technology Learning Technologist of the Year Awards celebrate and reward excellent practice and outstanding achievement in the learning technology field. The Awards are open to individuals and teams based anywhere in the world. They celebrate and reward excellent practice and outstanding achievement in the learning technology field and promote intelligent use of Learning Technology on a national scale. The Awards were supported by CoSector – University of London and were presented at the 2016 ALT Annual conference in Warwick on the evening of 7 September 2016. This year, we also celebrate 10 years of the Award. Turn over for details of the winners not only of this year’s Award but also for an overview of the last 10 years. Individual Awards Winner Daniel Scott, Barnsley College Daniel’s submission describes his journey as he extended his role as a Learning Technologist and the milestones he achieved. Daniel dedicated himself to training and developing a new Instructional Designer and Learning Technologist workforce, through the Digital Learning Design qualification suite. Daniel went above and beyond his role, and he designed, delivered, assessed and managed the Level 4 Certificate in Technology in Learning Delivery to staff. He is highly proactive, reflective and evaluative of his experiences and professionalism through his personal and professional blog, which enables him to inform his and the organisation’s development. Runner-up Chrissi Nerantzi, Manchester Metropolitan University Chrissi works as an academic developer in the Centre for Excellence in Learning and Teaching at Manchester Metropolitan University. -

Derby, Derbyshire, Nottingham, Nottinghamshire Area Review College Annex

Derby, Derbyshire, Nottingham, Nottinghamshire Area Review College annex August 2017 Contents1 Bilborough Sixth Form College 3 Central College Nottingham and New College Nottingham 4 Chesterfield College 6 Derby College 8 Portland College 10 Vision West Nottinghamshire College 11 1 Please note that the information on the colleges included in this annex relates to the point at which the review was undertaken. No updates have been made to reflect subsequent developments or appointments since the completion of the review. 2 Bilborough Sixth Form College Type: Sixth-form college Location: The college is based in Nottingham Local Enterprise Partnership: D2N2 LEP Principal: Chris Bradford Corporation Chair: Eileen Hartley Main offer includes: The college offers some technical education, but mainly delivers academic A level provision for 16 to 18 year olds across a range of subject areas. Details about the college offer can be reviewed on the Bilborough Sixth Form College website Specialisms: Bilborough Sixth Form College is the largest specialist deliverer of A levels to 16-18 year olds in the review area. The most popular curriculum areas at the college are science and mathematics, business, administration and law and languages, literature and culture The college receives funding from: Education Funding Agency For the 2014 to 2015 academic year, the college’s total income was: £9,035,000 Ofsted inspections: The college was inspected in September 2016 and was assessed as good 3 Central College Nottingham and New College Nottingham Type: General further education college Location: Central College Nottingham currently operates from over 10 sites in Nottingham City and Nottinghamshire, and New College Nottingham operates from 4 campuses In 2015, the Further Education Commissioner conducted a review of technical education in the City of Nottingham. -

HTS WEB Report Processor V2.1

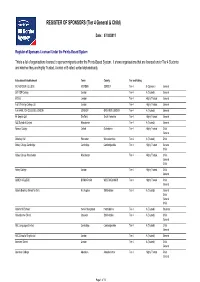

REGISTER OF SPONSORS (Tier 4 General & Child) Date : 22/06/2011 Register of Sponsors Licensed Under the Points-Based System This is a list of organisations licensed to sponsor migrants under the Points-Based System. It shows organisations that are licensed under Tier 4 Students and whether they are Highly Trusted, A-rated or B-rated, sorted alphabetically. Educational Establishment Town County Tier and Rating 3 D MORDEN COLLEGE MORDEN SURREY Tier 4 A (Trusted) General 360 GSP College London Tier 4 A (Trusted) General 4N ACADEMY LIMITED London Tier 4 B (Sponsor) General 5 E Ltd London Tier 4 Highly Trusted General A & S Training College Ltd London Tier 4 Highly Trusted General A A HAMILTON COLLEGE LONDON LONDON GREATER LONDON Tier 4 A (Trusted) General A+ English Ltd Sheffield South Yorkshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted General A2Z School of English Manchester Tier 4 A (Trusted) General Abacus College Oxford Oxfordshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted General Child Abberley Hall Worcester Worcestershire Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child Abbey College Cambridge Cambridge Cambridgeshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted General Child Abbey College Manchester Manchester Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child General Abbey College London Tier 4 Highly Trusted General Child ABBEY COLLEGE BIRMINGHAM WEST MIDLANDS Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child General Abbots Bromley School for Girls Nr. Rugeley Staffordshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted General Child Abbot's Hill School Hemel Hempstead Hertfordshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted Students Abbotsholme School Uttoxeter Staffordshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child -

Design of a Virtual Learning Environment for Students with Special Needs

An Interdisciplinary Journal on Humans in ICT Environments ISSN: 1795-6889 www.humantechnology.jyu.fi Volume 2 (1), April 2006, 119-153 DESIGN OF A VIRTUAL LEARNING ENVIRONMENT FOR STUDENTS WITH SPECIAL NEEDS Martin Maguire Edward Elton Ergonomics and Safety Research Institute Ergonomics and Safety Research Institute Loughborough University, UK Loughborough University, UK Zaheer Osman Colette Nicolle Active Ergonomics, Orangebox Ergonomics and Safety Research Institute Hengoed, UK Loughborough University, UK Abstract: The European Social Fund-supported Portland Partnership project developed a computer-based virtual learning environment (VLE) to benefit students with cognitive and physical disabilities. This system provided students with access to a suite of software programs to teach them basic/essential skills needed for everyday life and to use information and communications technology (ICT). The VLE can be customized to meet individual students’ needs by selecting an input device, adjusting its setting, or choosing a symbol set to support on-screen text. The learning programs within the VLE required careful design to make them stimulating and beneficial to students who have diverse health conditions and disabilities. The VLE and learning programs were evaluated within four partner Colleges of Further Education. Observations showed that students enjoyed the learning tools and the tutor comments indicated that students also benefited from them. A series of guidelines were identified for the design of future VLEs and learning software for students with special needs. Keywords: virtual learning environment, learning programs, special needs, physical and cognitive disabilities, human-computer interaction. INTRODUCTION Students with severe disabilities and special needs may suffer from a wide range of communication and learning impairments. -

Contents Qualifications – Awarding Bodies

Sharing of Personal Information Contents Qualifications – Awarding Bodies ........................................................................................................... 2 UK - Universities ...................................................................................................................................... 2 UK - Colleges ........................................................................................................................................... 6 Glasgow - Schools ................................................................................................................................. 12 Local Authorities ................................................................................................................................... 13 Sector Skills Agencies ............................................................................................................................ 14 Sharing of Personal Information Qualifications – Awarding Bodies Quality Enhancement Scottish Qualifications Authority Joint Council for Qualifications (JCQ) City and Guilds General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) General Certificate of Education (GCE) Edexcel Pearson Business Development Royal Environmental Health Institute for Scotland (REHIS) Association of First Aiders Institute of Leadership and Management (ILM) Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (IOSH) UK - Universities Northern Ireland Queen's – Belfast Ulster Wales Aberystwyth Bangor Cardiff Cardiff Metropolitan South Wales -

HTS WEB Report Processor V2.1

REGISTER OF SPONSORS (Tier 4 General & Child) Date : 07/02/2011 Register of Sponsors Licensed Under the Points-Based System This is a list of organisations licensed to sponsor migrants under the Points-Based System. It shows organisations that are licensed under Tier 4 Students and whether they are Highly Trusted, A-rated or B-rated, sorted alphabetically. Educational Establishment Town County Tier and Rating 3 D MORDEN COLLEGE MORDEN SURREY Tier 4 B (Sponsor) General 360 GSP College London Tier 4 A (Trusted) General 5 E Ltd London Tier 4 Highly Trusted General A & S Training College Ltd London Tier 4 Highly Trusted General A A HAMILTON COLLEGE LONDON LONDON GREATER LONDON Tier 4 A (Trusted) General A+ English Ltd Sheffield South Yorkshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted General A2Z School of English Manchester Tier 4 A (Trusted) General Abacus College Oxford Oxfordshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child General Abberley Hall Worcester Worcestershire Tier 4 A (Trusted) Child Abbey College Cambridge Cambridge Cambridgeshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted General Child Abbey College Manchester Manchester Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child General Child Abbey College London Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child General ABBEY COLLEGE BIRMINGHAM WEST MIDLANDS Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child General Abbots Bromley School for Girls Nr. Rugeley Staffordshire Tier 4 A (Trusted) General Child General Child Abbot's Hill School Hemel Hempstead Hertfordshire Tier 4 A (Trusted) Students Abbotsholme School Uttoxeter Staffordshire Tier 4 A (Trusted) Child General ABC Languages Limited Cambridge -

Clubs and Institutions by Institution

clubs and institutions By Institution Educational Institution Club A Plus English Limited Sheffield A+ English Language School Sheffield A+ English Ltd Sheffield A2Z School of English Manchester Abbey College London Aberystwyth University Swansea Acton High School Sixth Form London Alderwasley Hall School Surrey Angel Language Academy Southampton Anglia Ruskin University Cambridge Anglo-Continental Birmingham Anglo-Continental Preston Anglo-Continental Southampton Anglolang Academy of English York Ashfield School Leicester Aston University Birmingham Bangor University Bangor Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry Part of Queen Mary - University of London London Basil Paterson College Edinbugh Bath Academy Bath BEET Language Centre Southampton Berlitz Manchester Manchester Bilston Community College Birmingham Birkbeck - University of London London BIRMINGHAM CAMPUS- london school of business & finance Birmingham Birmingham City University Birmingham Birmingham College Birmingham Bloomsbury International London Bournemouth Academy Southampton Bournemouth Business School International - BBSI Southampton Bournemouth University Southampton Bournville College Birmingham BPP University College of Professional Studies London BPP University College of Professional Studies Limited London Bradford College Leeds Bradford Metropolitan College Leeds Brasshouse Language Centre Birmingham Bright Bees Day Nursery Leicester Brighton Day Options Brighton Brighton Language College Brighton Bristol University Bristol British International School -

Year Book 2017

Project Year Book 2017 Great to work with. Great to work for. architecture / interiors / landscape / masterplanning Contents Project Coverage 3 RIBA Stages 3 and 4 RIBA Stage 5 RIBA Stage 6 Developed Design / Technical Design Construction Handover and Close Out Foreword Mark Hobson - Managing Director 4 • Portland College Activity Centre, • Saffron Court, Nottingham 51 • ISTeC STEM Laboratories, The People 5 Ashfeld 33 Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham 69 • Newark Fire Station, Newark 53 Clients 7 • Bemrose School, Derby 34 • Turves Green Boys’ School, Birmingham 71 • Aldi, Sherwood Oaks, Mansfeld 54 Awards 8 • NTU Engineering and IIDRA • Priority Schools Building Programme 73 Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham 35 • ROMO Fabrics, Nottinghamshire 55 - Hertfordshire maber News 9 • Radcliffe Road Stand Extension, - Luton • Bishop Ellis School, Leicester 37 Trent Bridge Cricket Ground, Nottingham 59 - Reading • Short Hill, The Lace Market, • Akaal Primary School, Derby 61 • Priority Schools Building Programme Nottingham 39 Landscape Design 75 RIBA Stages 1 and 2 • Sutherland Primary School, Stoke 63 Preparation and Brief / Concept Design • Spa Road, Bermondsey 41 • Leicester Castle Business School, • Junior School Extension, De Montfort University, Leicester 77 • Guildhall Place, Nottingham 43 Nottingham High School, Nottingham 64 • No 7 Market Place, Derby 17 • Lumis, Leicester 79 • ROMO Fabrics - Landscape, • Wilsthorpe Community School, Long Eaton 65 • Guildhall Place, Nottingham 18 Nottinghamshire 45 • Lumis - Landscape, Leicester -

Project Year Book 2015/16

Project Year Book 2015/16 Great to work with. Great to work for. architecture / interiors / landscape / masterplanning Contents RIBA Stage 5 • Premier Inn, Derby 71 Construction Project Coverage 3 • Leicester Enterprise House, Leicester 25 • AgriSTEM Campus, Rodbaston 72 • Junior School Extension, Foreword • Technology Entrepreneurship Centre, • Brooksby Melton College Campuses, Leicestershire 73 Mark Hobson - Managing Director 4 The University of Nottingham 26 Nottingham High School, Nottingham 49 • Rolls-Royce On Wing Repair Centre, Heathrow 77 The People 5 • Sherwood Forest Visitor Centre, • Trelleborg Centre of Excellence, Retford 51 Nottinghamshire 27 • Derby Manufacturing UTC, Derby 78 Clients 7 • Radcliffe Road Stand Extension, • Industrial Campus, Derby 29 Trent Bridge Cricket Ground, Nottingham 52 • Controls and Data Services, Solihull 79 Awards 8 • New facility for Engineering, • Knowsley Community College, Liverpool 83 RIBA Stages 3 and 4 Computer Science and Maths, University of Lincoln 53 • WMG Academy for Young Engineers, Solihull 87 RIBA Stages 1 and 2 Developed Design / Technical Design • Lumis, Leicester 55 Preparation and Brief / Concept Design • Space2 Creative Centre, Nottingham 91 • Portland College, Mansfeld 33 • ISTEC STEM Laboratories, • East Hampshire Leisure Centres 11 • Saffron Court, Nottingham 34 Nottingham Trent University 57 • Medway UTC, Kent 93 • Angel Row Development, Nottingham 13 • Guernsey College of Further Education, • One Hockley, Nottingham 59 • Rolls-Royce XWB, Derby 94 • G-ERA Building, Guernsey