Collective Identities in Baltic and East Central Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winners of the Baltic Assembly Prizes 1994 – 2019 1994 1996 1998

Baltic Assembly Prizes for Literature, the Arts and Science Baltic Innovation Prize Baltic Assembly Medals 6 November 2020 Address by the President of the Baltic Assembly Aadu Must This year the Baltic Assembly, as any contribute to the targeted cooperation of other organisation, has been significantly our states and prosperity of our Baltic affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. region that will be extremely important Despite the difficulties and restrictions to in the years to come. These people meet in person, the traditions of our promote the unity and cooperation of organisation continue but in slightly the Baltic states - we greatly appreciate different format this year. their work. We award the Baltic Assembly Prizes to Unity and cooperation of the Baltic states outstanding people, who have are extremely important for us. We are demonstrated excellence in literature, thankful to all people who feel the same the arts, science and innovation. This way and act in order to bring the countries year’s winners of the Baltic Assembly closer together. The awarding of the Baltic Prizes have used their talent and Assembly Prizes and Medals in Estonia, knowledge to encourage thinking, remind Lithuania and Latvia is our way of saying about the historical milestones of that even though times are tough people are those who hold our nations together Photo by Ieva Ābele (Administration of Parliament of the Republic of Latvia) the Baltic states and make our countries visible in the international arena. Awards and we are grateful for that. We are also have been won in strong competition, as very proud about their achievements. -

UNU CRIS Working Papers

1 | P a g e The author Andrea Cofelice served as Ph.D. Intern at UNU-CRIS in 2011. He is currently a Ph.D. candidate in Political Science – Comparative and European Politics at the University of Siena. He is also a junior researcher at the Interdepartmental Centre on Human Rights and the Rights of Peoples of the University of Padua. United Nations University Institute on Comparative Regional Integration Studies Potterierei 72, 8000 Brugge, BE-Belgium Tel.: +32 50 47 11 00 / Fax.: +32 50 47 13 09 www.cris.unu.edu 2 | P a g e Abstract This paper aims at exploring which factors may promote or inhibit the empowerment of international parliamentary institutions (IPIs). According to the literature (Cutler 2006), an IPI may be defined as an international institution that is a regular forum for multilateral deliberations on an established basis of an either legislative or consultative nature, either attached to an international organization or itself constituting one, in which at least three states or trans-governmental units are represented by parliamentarians, who are either selected by national legislatures in a self-determined manner or popularly elected by electorates of the member states. Their origin dates back to the creation of the Inter- Parliamentary Union (IPU) in 1889, but they mushroomed after the Second World War, especially after 1989-1991 (new regionalism, also known as open regionalism especially in literature on Latin America), and today their presence is established almost everywhere in the world. However, they display sensibly different features in terms of institutional and organizational patterns, rules and procedures, legal status, membership, resources, functions and powers. -

The Day Holding Hands Changed History Occupation and Annexation of the Baltic States Was Illegal, and Against the Wish of the Respective Nations

The day holding hands changed history occupation and annexation of the Baltic states was illegal, and against the wish of the respective nations. So at 19:00 on 23 August 1989, 50 years after the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was signed, church bells sounded in the Bal- tic states. Mourning ribbons decorated the national flags that had been banned a year before. The participants of the Bal- tic Way were addressed by the leaders of the respective national independence movements: the Estonian Rahvarinne, the Lithuanian Sajūdis, and the Popular Front of Latvia. The following words were chanted – ‘laisvė’, ‘svabadus, ‘brīvība’ (freedom). The symbols of Nazi Germany and the Communist regime of the USSR were burnt on large bonfires. The Baltic states demanded the cessation of the half-century long Soviet occupation, col- onisation, russification and communist genocide. The Baltic Way was a significant step to- wards regaining the national independ- ence of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia, and a source of inspiration for other region- al independence movements. The live chain was also realised in Kishinev by Ro- manians of the Soviet-occupied Bessara- bia or Moldova, while in January 1990, Ukrainians joined hands on the road from Lviv to Kyiv. Just after the Baltic Way campaign, the Berlin Wall fell, the Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia began, and the Ceausescu regime in Romania was overthrown. On 23 August 1989, approximately two doomed to be forcedly incorporated into million people stood hand in hand be- the Soviet Union until 1991. The Soviet Un- Recognising the documents of the Baltic tween Tallinn (Estonia), Rīga (Latvia) ion claimed that the Baltic states joined Way as items of documentary heritage of and Vilnius (Lithuania) in one of the voluntarily. -

NATO, the Baltic States, and Russia a Framework for Enlargement

NATO, the Baltic States, and Russia A Framework for Enlargement Mark Kramer Harvard University February 2002 In 2002, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) will be initiating its second round of enlargement since the end of the Cold War. In the late 1990s, three Central European countries—Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Poland—were admitted into the alliance. At a summit due to be held in Prague in November 2002, the NATO heads-of-state will likely invite at least two and possibly as many as six or seven additional countries to join. In total, nine former Communist countries have applied for membership. Six of the prospective new members—Slovakia, Slovenia, Bulgaria, Romania, Albania, and Macedonia—lie outside the former Soviet Union. Of these, only Slovakia and Slovenia are likely to receive invitations. The three other aspiring members of NATO—Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia— normally would stand a good chance of being admitted, but their status has been controversial because they were republics of the Soviet Union until August 1991. Until recently, the Russian government had vehemently objected to the proposed admission of the Baltic states into NATO, and many Western leaders were reluctant to antagonize Moscow. During the past year-and-a-half, however, the extension of NATO membership to the Baltic states in 2002 has become far more plausible. The various parties involved—NATO, the Baltic states, and Russia—have modified their policies in small but significant ways. Progress in forging a new security arrangement in Europe began before the September 2001 terrorist attacks, but the improved climate of U.S.-Russian relations since the attacks has clearly expedited matters. -

Silke Berndsen Outlook on Baltic Cooperation 1945-2004 at the First

Silke Berndsen Outlook on Baltic Cooperation 1945-2004 At the First Baltic Assembly the Estonian Mati Hint evoked the unity of the Baltic nations in his manifesto “the Baltic Way". The Baltic way soon after became known beyond the three Baltic states when approximately two million people joined their hands to form a human chain across the three Baltic states on 23 August 1989 during a a peaceful political demonstration that carried the same name. In the months that followed, the popular fronts made numerous joint appeals to international organizations and foreign governments. When they had declared independence from the Soviet Union, the governments of the Baltic States were quick to renew the suspended Baltic Treaty on Unity and Cooperation signed on 12 September 1934 with an explicit reference to the "historical experience of our trilateral cooperation" and with the aim to "continue and develop political and economic cooperation among our three states". Only a few years later, the Baltic States argued over border demarcations between their countries, fought "egg wars", "herring wars", "pork wars" and competed as to which of them would be the first to join the EU and NATO. Prominent politicians in Estonia and Lithuania no longer wanted their countries to be labelled as "Baltic", but as “Nordic“ (in case of Estonia) or Central European (in case of Lithuania). So, what had happened? Did Baltic ceased to serve as an identity anchor just within a few years? And what did this mean for cooperation among the Baltic states, which was initiated by the 1990 Treaty and further institutionalised in subsequent years? Based on constructivist approaches in cultural studies, my presentation assumes that territorial spaces are analytical categories with context-dependent attributions. -

The Baltic Assembly

Assembly of Western European Union DOCUMENT 1460 22nd May 1995 FORTIETH ORDINARY SESSION (Third Part) The Baltic Assembly REPORT submitted on behalf of the Committee for Parliamentary and Public Relations by Mr. Masseret, Chairman and Rapporteur ASSEMBLY OF WESTERN EUROPEAN UNION 43, avenue du President-Wilson, 75775 Paris Cedex 16-Tel. 53.67.22.00 Document 1460 22nd May 1995 The Baltic Assembly REPORT 1 submitted on behalf of the Committee for Parliamentary and Public Relations 2 by Mr. Masseret, Chairman and Rapporteur TABLE OF CONTENTS DRAFr0RDER on the Baltic Assembly EXPLANATORY MEMORANDUM submitted by Mr. Masseret, Chairman and Rapporteur I. Introduction II. Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania: from political to parliamentary co-operation (a) Inter-state co-operation ( i) The Baltic Council (ii) Prospects for inter-state co-operation (b) Inter-regional co-operation (i) Nordic and Baltic co-operation (ii) European and transatlantic co-operation m. The Baltic Assembly: role and prospects (a) The political role of Baltic interparliamentary co-operation (i) co-operation between the Baltic Council and the Baltic Assembly (ii) The way the Assembly operates (b) The Baltic Assembly: regional and European political perspectives (i) Inter-state security and defence co-operation ( ii) Regional and European policy - Relations with the Russian Federation - European co-operation 1. Adopted unanimously by the committee. 2. M embers ofthe committee: Mr. Masseret (Chairman); Sir Russell J ohnston, Baroness Gould ofPotternewton (Vice-Chairmen); Mr. Amaral, Mrs. Beer, MM. Benvenuti, Birraux, Decagny, Dionisi, Sir Anthony Durant (Alternate: Baroness Hooper), Mr. Erler, Mrs. Err (Alternate: Mrs. Brasseur), Mr. Eversdijk, Mrs. Fernandez Sanz, MM. -

Eu Baltic Sea Strategy

EU BALTIC SEA STRATEGY REPORT FOR THE KONRAD-ADENAUER-STIFTUNG LONDON OFFICE www.kas.de This paper includes résumés and experts views from conferences and seminars facilitated and organised by the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung London and Centrum Balticum. Impressum © Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronical or mechanical, without permission in writing from Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, London office, 63D Eccleston Square, London SW1V 1PH. ABBREVIATIONS AC Arctic Council AEPS Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy ALDE Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe BaltMet Baltic Metropoles BCCA Baltic Sea Chambers of Commerce Association BDF Baltic Development Forum BEAC Barents Euro-Arctic Council BEAR Council of the Barents Euro-Arctic Region BENELUX Economic Union of Belgium, The Netherlands and Luxembourg BFTA The Baltic Free Trade Area BSCE Black Sea Economic Cooperation Pact BSPC The Baltic Sea Parliamentary Conference BSR Baltic Sea Region BSSSC Baltic Sea States Subregional Cooperation CBSS The Council for Baltic Sea States CFSP Common Foreign and Security Policy CEFTA Central European Free Trade Agreement CIS The Commonwealth of Independent States COMECON Council for Mutual Economic Assistance CPMR Conference of Peripheral Maritime Regions of Europe EBRD European Bank for Reconstruction and Development EEA European Economic Area EEC European Economic Community EFTA European Free Trade Agreement EGP European Green Party ENP European -

Baltic Alliance for Apprenticeships (Bafa) Enhancing the Attractiveness of VET Systems in the Baltic States Through Work-Based Learning and Apprenticeships

Baltic Alliance for Apprenticeships (BAfA) Enhancing the attractiveness of VET systems in the Baltic states through work-based learning and apprenticeships LITHUANIA, LATVIA, ESTONIA Title of the practice (in Baltijas māceklības alianse original language) Who is implementing the • Ministry of Education and Science, Latvia practice? • Ministry of Education and Science, Lithuania • Ministry of Education and Research, Estonia Which other • Social partners: Employers’ Confederation of Latvia, Free Trade Union organisations are Confederation of Latvia involved in the practice? • National Centre for Education of Latvia • Qualifications and Vocational Education and Training Development Centre, Lithuania • Foundation Innove, Estonia What are the main BAfA aims to raise the status and enhance the attractiveness of VET in the Baltic objectives of the states by involving national social partners and VET provider organisations in practice? the development of effective approaches. Particular emphasis is placed on the promotion and implementation of work-based learning (WBL) and apprenticeship- type schemes. When was the practice Since 2015 (ongoing) implemented? Who is targeted by the VET stakeholders in the Baltic states practice? What activities are/were • Studies on work-based learning feasibility and implementation. carried out? • Technical assistance to national VET stakeholders in the form of expert working groups, round table discussions, information and dissemination seminars. • VET and work-based learning promotion campaigns. • Joint Baltic-wide -

The Foreign Policy of Russia : Changing Systems, Enduring Interests / by Robert H

RUSSIATHE FOREIGN POLICY OF This page intentionally left blank RUSSIATHE FOREIGN POLICY OF CHANGING SYSTEMS, ENDURING INTERESTS FIFTH EDITION ROBERT H. DONALDSON JOSEPH L. NOGEE AND VIDYA NADKARNI ROUTLEDGE Routledge Taylor & Francis Group LONDON AND NEW YORK First published 2014 by M.E. Sharpe Published 2015 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Copyright © 2014 Taylor & Francis. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Notices No responsibility is assumed by the publisher for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use of operation of any methods, products, instructions or ideas contained in the material herein. Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility. Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Donaldson, Robert H., author. -

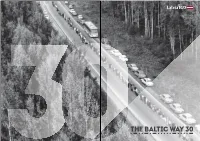

The Baltic Way Towards Freedom

THE BALTIC The Baltic Way WAY 30 Towards Freedom At 19:00 on 23 August 1989 approximately two million people of the Baltic states joined hands forming a live, continuous chain on the road Tallinn-Rīga-Vilnius (660-670 km). Church bells sounded in the Baltic states. Mourning ribbons decorated the national flags that were banned a year ago. The participants of the Baltic Way were addressed by the leaders of Rahvarinne - the Estonian Popular Front, the Lithuanian movement Sajūdis and the Popular Front of Latvia. The following words were heard – ‘laisvė’, ‘svabadus, ‘brīvība’ (freedom). The symbols of Nazi Germany and the Communist regime of the USSR were burned in large bonfires. Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania engaged in collective action against the non-assault agreement between Hitler and Stalin of 23 August 1939 and its secret protocols or the “devil pact”. The Baltic states demanded the cessation of half-century long Soviet occupation, colonisation, russification and Photo 1 (cover photo) communist genocide. The Baltic Way became the The Baltic Way on Pleskava highway. crucial application by the Baltic states’ civil society The photo was taken from the helicopter for independence and return to Europe. It was the on 23 August 1989. first dice in the domino effect that disrupted the Photographer Aivars Liepiņš. Archive of the Latvian Institute. totalitarian regime in Eastern Europe - the first step towards regaining national independence of Latvia. © State Chancellery of Latvia, 2019 THE BALTIC WAY 30 1 2 THE BALTIC WAY 30 Photo 2 Causes and Participants of the Baltic Way on the Stone Bridge (at that time the October Bridge). -

Roadmap for the Baltic Sea Region

Roadmap for the Baltic Sea Region Cultural Routes | 2 Routes Cultural Heritage protection, cultural tourism and transnational co-operation through the Cultural Routes Cultural Routes | 2 Roadmap for the Baltic Sea Region Roadmap for Routes4U Project Roadmap for the Baltic Sea Region Heritage protection, cultural tourism and transnational co-operation through the Cultural Routes Cultural Routes | 2 Council of Europe Table of content FOREWORD 4 INTRODUCTION 6 PART I – OVERVIEW OF THE CULTURAL ROUTES OF THE COUNCIL OF EUROPE PROGRAMME AND THE EU STRATEGY FOR THE BALTIC SEA REGION 9 1. THE CULTURAL ROUTES OF THE COUNCIL OF EUROPE 10 1.1. Historic context 10 1.2. Definition 11 1.3. Institutional structure 12 1.4. Creation of a Cultural Route 14 1.5. Key features 16 2. THE BALTIC SEA REGION 20 2.1. European Union Strategy for the Baltic Sea Region 21 2.2. The role of cultural tourism for the region 24 3. ANALYSIS OF THE CULTURAL ROUTES IN THE BALTIC SEA REGION 25 3.1. Geographical framework of Cultural Routes in the Baltic Sea Region 25 3.2. Sectorial framework of Cultural Routes in the Baltic Sea Region 26 3.3. Thematic framework of Cultural Routes in the Baltic Sea Region 28 3.4. Summary 29 4. IMPACT OF CULTURAL ROUTES ON REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT 30 4.1. Economic impact 30 4.2. Social impact 32 5. ROUTES4U PROJECT 33 5.1. Identification of Cultural Routes priorities for the Baltic Sea Region 34 5.2. Extension of certified Cultural Routes 35 5.3. Bibliography 36 PART II – EXPERTS REPORTS ON REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT THROUGH THE CULTURAL ROUTES IN THE BALTIC SEA REGION 39 1. -

Keynote Speeches

KEYNOTE SPEECHES Mr Dariusz Rosati Minister of Foreign Affairs of Republic of Poland Mr Pierre Schori Minister for International Development Cooperation of Sweden Mrs Monika Wulf-Mathies Commissioner for Regional Policies, European Commission Mr Dan Nielsen Chairman of the Committee of Senior Officials of CBSS Mr Olof Salmen President of the Nordic Council Mr Knud Andersen Speaker of the Baltic Sea States Subregional Cooperation Mr Hannu Tapiola President of CPMR Baltic Sea Commission Mr Wolf-Rudiger Janzen President of Baltic Sea Chambers of Commerce Association Mr Dariusz Rosati Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland Mr Chairman! Excellencies! Ladies and Gentlemen! In my first words I would like to express my satisfaction with hosting you, members of the Union of the Baltic Cities in Gdansk which celebrates this year the 1000th anniversary. Using this opportunity I wish you interesting discussion and promising exchange of your experience. Poland attaches a great importance to the cooperation in this region and especially between Baltic cities. As an example of this approach is the fact that UBC was founded in 1991 in Gdansk among others on Polish initiative. In our opinion the Union of the Baltic Cities is one of the most active organisation in the network of Baltic Sea institutions. We believe that today the Union has so much capacities to act as good and efficient as its great predecessor - the Hanse which was the first great regional organisation in Baltic Sea region. The participation in the Hanse was a source of the faster development and growing prosperity for its members and for the whole Baltic region.