UNU CRIS Working Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winners of the Baltic Assembly Prizes 1994 – 2019 1994 1996 1998

Baltic Assembly Prizes for Literature, the Arts and Science Baltic Innovation Prize Baltic Assembly Medals 6 November 2020 Address by the President of the Baltic Assembly Aadu Must This year the Baltic Assembly, as any contribute to the targeted cooperation of other organisation, has been significantly our states and prosperity of our Baltic affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. region that will be extremely important Despite the difficulties and restrictions to in the years to come. These people meet in person, the traditions of our promote the unity and cooperation of organisation continue but in slightly the Baltic states - we greatly appreciate different format this year. their work. We award the Baltic Assembly Prizes to Unity and cooperation of the Baltic states outstanding people, who have are extremely important for us. We are demonstrated excellence in literature, thankful to all people who feel the same the arts, science and innovation. This way and act in order to bring the countries year’s winners of the Baltic Assembly closer together. The awarding of the Baltic Prizes have used their talent and Assembly Prizes and Medals in Estonia, knowledge to encourage thinking, remind Lithuania and Latvia is our way of saying about the historical milestones of that even though times are tough people are those who hold our nations together Photo by Ieva Ābele (Administration of Parliament of the Republic of Latvia) the Baltic states and make our countries visible in the international arena. Awards and we are grateful for that. We are also have been won in strong competition, as very proud about their achievements. -

Arab Maghreb Union: Achievement and Prospects

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 1994-06 Arab Maghreb Union: achievement and prospects Messaoudi, Abderrahmen Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/42905 (/) NAVAL POSTGRADUA1E SCHOOL Monterey, California AD-A283 604 1111111111!111111 !II~ 11111111111111111111111 THESIS ARAB MAGHREB UNION: ACHIEVEMENT AND PROSPECTS by Abderrahmen Messaoudi June, 1994 Thesis Advisor: Kamil. T Said Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. 94-26907 ~ II~IUI~mm11~ 94 8 23 REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Fonn Approved OMB No. 0704 Public: rc:pcrtiDa burdcll for Ibis coUa:tioo of illformalioo is eslim.rcd 10 average 1 hour per respoosc, iDc1udiDg tbc time for revicwiD& ill.llniCtioll. ICII'Cbiag existing dala soun:cs, galbcriDg and mainlaiJUag lbe dala occdcd. and complelillg and rcviewiag lbe collcclioo of illformalioo. Sead commcala rcg•diDg Ibis burden estimarc or aay olber aspect of Ibis coUa:tioo of illformalioo, including suggeslioos for rcduciDg Ibis burdca, 10 Wasbiagtoa Hcadquancn Services, Dircctorare for laformalioo Opcrllioas aad Reports, 121S Jeffcrsoa Davis Highway, Suire 1204, Arliagtoa, VA 222024302. and 10 tbc Office of M~~~agcmeat aad Budget, Papcrwort Rcduclioo Project (0704-0188) Wasbiogtoa DC 20S03. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED 1994 June Master's Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITI.E Arab Maghreb Union : Achievement and 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Prospects 6. AUTHOR(S) Abderrahmen Messaoudi. 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING Naval Postgraduate School ORGANIZATION Monterey CA 93943-5000 REPORT NUMBER 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY REPORT NUMBER 11. -

The Day Holding Hands Changed History Occupation and Annexation of the Baltic States Was Illegal, and Against the Wish of the Respective Nations

The day holding hands changed history occupation and annexation of the Baltic states was illegal, and against the wish of the respective nations. So at 19:00 on 23 August 1989, 50 years after the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was signed, church bells sounded in the Bal- tic states. Mourning ribbons decorated the national flags that had been banned a year before. The participants of the Bal- tic Way were addressed by the leaders of the respective national independence movements: the Estonian Rahvarinne, the Lithuanian Sajūdis, and the Popular Front of Latvia. The following words were chanted – ‘laisvė’, ‘svabadus, ‘brīvība’ (freedom). The symbols of Nazi Germany and the Communist regime of the USSR were burnt on large bonfires. The Baltic states demanded the cessation of the half-century long Soviet occupation, col- onisation, russification and communist genocide. The Baltic Way was a significant step to- wards regaining the national independ- ence of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia, and a source of inspiration for other region- al independence movements. The live chain was also realised in Kishinev by Ro- manians of the Soviet-occupied Bessara- bia or Moldova, while in January 1990, Ukrainians joined hands on the road from Lviv to Kyiv. Just after the Baltic Way campaign, the Berlin Wall fell, the Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia began, and the Ceausescu regime in Romania was overthrown. On 23 August 1989, approximately two doomed to be forcedly incorporated into million people stood hand in hand be- the Soviet Union until 1991. The Soviet Un- Recognising the documents of the Baltic tween Tallinn (Estonia), Rīga (Latvia) ion claimed that the Baltic states joined Way as items of documentary heritage of and Vilnius (Lithuania) in one of the voluntarily. -

Trade and Conflict: the Case of the Arab Maghreb Union

Topics in Middle Eastern and African Economies Proceedings of Middle East Economic Association Vol. 20, Issue No. 2, September 2018 Trade and Conflict: The Case of the Arab Maghreb Union Rayhana Chabbouh El Asmi University of Tunis El Manar Faculty of Economics and Management of Tunis Research Laboratory «Prospective, Stratégies et Développement Durable (PS2D) » [email protected] Abstract- This paper explores the links between trade, conflict and peace in the Arab Maghreb countries. Since its creation in 1989, the Arab Maghreb Union (AMU) has been in a lethargic state. We assume that reducing inter and intra-state conflicts would be a sound argument for the reactivation of the Arab Maghreb Union. In this paper, we will discuss trade flows between the Maghreb Union countries and highlight the pending political issues and conflicts. The results confirm that countries which are more likely to create regional blocks are naturally more open to trade and even more subject to interstate disputes. Elimination of all trade barriers and putting into effect multilateral trading systems would enable AMU countries the creation of a regional security framework that leverages diplomatic, political, economic and even military resources. Regional integration can be built and strengthened in order to promote peace and stability. Keywords – trade, conflict, peace, regional trade agreements, geographic proximity, Arab Maghreb Union. JEL – F01, F15, F51, D74, C23 90 Topics in Middle Eastern and African Economies Proceedings of Middle East Economic Association Vol. 20, Issue No. 2, September 2018 1. Introduction The relationship between international trade and security has been long known for centuries. -

NATO, the Baltic States, and Russia a Framework for Enlargement

NATO, the Baltic States, and Russia A Framework for Enlargement Mark Kramer Harvard University February 2002 In 2002, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) will be initiating its second round of enlargement since the end of the Cold War. In the late 1990s, three Central European countries—Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Poland—were admitted into the alliance. At a summit due to be held in Prague in November 2002, the NATO heads-of-state will likely invite at least two and possibly as many as six or seven additional countries to join. In total, nine former Communist countries have applied for membership. Six of the prospective new members—Slovakia, Slovenia, Bulgaria, Romania, Albania, and Macedonia—lie outside the former Soviet Union. Of these, only Slovakia and Slovenia are likely to receive invitations. The three other aspiring members of NATO—Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia— normally would stand a good chance of being admitted, but their status has been controversial because they were republics of the Soviet Union until August 1991. Until recently, the Russian government had vehemently objected to the proposed admission of the Baltic states into NATO, and many Western leaders were reluctant to antagonize Moscow. During the past year-and-a-half, however, the extension of NATO membership to the Baltic states in 2002 has become far more plausible. The various parties involved—NATO, the Baltic states, and Russia—have modified their policies in small but significant ways. Progress in forging a new security arrangement in Europe began before the September 2001 terrorist attacks, but the improved climate of U.S.-Russian relations since the attacks has clearly expedited matters. -

Silke Berndsen Outlook on Baltic Cooperation 1945-2004 at the First

Silke Berndsen Outlook on Baltic Cooperation 1945-2004 At the First Baltic Assembly the Estonian Mati Hint evoked the unity of the Baltic nations in his manifesto “the Baltic Way". The Baltic way soon after became known beyond the three Baltic states when approximately two million people joined their hands to form a human chain across the three Baltic states on 23 August 1989 during a a peaceful political demonstration that carried the same name. In the months that followed, the popular fronts made numerous joint appeals to international organizations and foreign governments. When they had declared independence from the Soviet Union, the governments of the Baltic States were quick to renew the suspended Baltic Treaty on Unity and Cooperation signed on 12 September 1934 with an explicit reference to the "historical experience of our trilateral cooperation" and with the aim to "continue and develop political and economic cooperation among our three states". Only a few years later, the Baltic States argued over border demarcations between their countries, fought "egg wars", "herring wars", "pork wars" and competed as to which of them would be the first to join the EU and NATO. Prominent politicians in Estonia and Lithuania no longer wanted their countries to be labelled as "Baltic", but as “Nordic“ (in case of Estonia) or Central European (in case of Lithuania). So, what had happened? Did Baltic ceased to serve as an identity anchor just within a few years? And what did this mean for cooperation among the Baltic states, which was initiated by the 1990 Treaty and further institutionalised in subsequent years? Based on constructivist approaches in cultural studies, my presentation assumes that territorial spaces are analytical categories with context-dependent attributions. -

The Arab Maghreb Union: Possibilities of Maghrebine Political and Economic Unity, and Enhanced Trade in the World Community Robert W

Penn State International Law Review Volume 10 Article 4 Number 2 Dickinson Journal of International Law 1-1-1992 The Arab Maghreb Union: Possibilities of Maghrebine Political and Economic Unity, and Enhanced Trade in the World Community Robert W. McKeon Jr. Follow this and additional works at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation McKeon, Robert W. Jr. (1992) "The Arab Maghreb Union: Possibilities of Maghrebine Political and Economic Unity, and Enhanced Trade in the World Community," Penn State International Law Review: Vol. 10: No. 2, Article 4. Available at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr/vol10/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn State Law eLibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Penn State International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Penn State Law eLibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Arab Maghreb Union: Possibilities of Maghrebine Political and Economic Unity, and Enhanced Trade in the World Community Robert W. McKeon, Jr.* I. Introduction On February 17, 1989, Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, and Tunisia signed the Treaty to Constitute the Union of the Arab Maghreb (Treaty) in Marrakesh, Morocco.' The Arab Maghreb Union (Union) now comprises sixty-two million people within a re- * J.D. Case Western Reserve University, 1991; M.A. Middlebury College, 1988; A.B. College of the Holy Cross, 1987. 1. The Treaty Creating the Union of the Arab Maghreb was supplied by the United States Department of State and translated from the original in Arabic [hereinafter AMU Treaty]. -

Collective Identities in Baltic and East Central Europe

1. Introduction: Collective Identities in Baltic and East Central Europe Norbert Götz After a preoccupation with collective identities culminated in the mass destruction of the Second World War and the Holocaust, and after the post- war remapping and resettlement was enforced, ethnic identity was ‘out’ for many decades as a political vehicle or a proper topic of research.1 The ideas of the behaviour of the individual and his or her gentle civilisation in the spirit of enlightenment took its place. Personal affiliation with a group was regarded as a functional piece in a greater puzzle of general progress; stronger types of identification that did not harmonise with the rationality of light bonds were believed to be doomed to vanish. Such modernism existed in a capitalist and a communist variety, with greater emphasis on the individual and the universal dimension respectively (in its communist version the universalism was a class-based projection). The suggestion that Sweden represents a ‘third way’, with a political culture that has been lauded as ‘statist individualism’ (Trägårdh 1997; see also Berggren and Trägårdh 2006), highlights the country’s peculiar status at the time of the Cold War (see Bjereld, Johansson, and Molin 2008). The lack of independent societal forces has given rise to a conformist, single norm-oriented Nordic Sonderweg (Stenius 2013). During the Cold War, both historical materialism and modernisation theory gave meaning to a bipolar world with its two competing universa- lisms aiming at humankind at large.2 There was an intellectual distance, 1 As a research concept, ‘identity’ was not in use until after the Second World War. -

Strengthening Popular Participation in the African Union a Guide to AU Structures and Processes

STRENGTHENING POPULAR PARTICIPATION IN THE AFRICAN UNION A Guide to AU Structures and Processes AfriMAP An Open Society Institute Network Publication In memory of Tajudeen Abdul Raheem Pan-Africanist 1961–2009 First published in 2009 by the Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa (OSISA) and Oxfam Copyright © 2009 Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa (OSISA) and Oxfam ISBN 978-1-920355-24-1 2nd impression 2010 All rights reserved. Redistribution of the material presented in this work is encouraged, provided that the original text is not altered, that the original source is properly and fully acknowledged and that the objective of the redistribution is not for commercial gain. Please contact [email protected] if you wish to reproduce, redistribute or transmit, in any form or by any means, this work or any portion thereof. Produced by COMPRESS.dsl www.compressdsl.com Contents Acknowledgements v Acronyms vi INTRODUCTION: THE PURPOSE OF THIS GUIDE 1 PART 1 AU ORGANS & INSTITUTIONS 3 > Assembly of Heads of State and Government 6 > Chairperson of the African Union 8 > Executive Council of Ministers 10 > Permanent Representatives Committee (PRC) 12 > Commission of the African Union 14 > Peace and Security Council (PSC) 18 > Pan-African Parliament (PAP) 21 > African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) 22 > African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child 24 > African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (to become the African Court of Justice and Human Rights) 25 > Economic, Social and Cultural Council (ECOSOCC) -

The Baltic Assembly

Assembly of Western European Union DOCUMENT 1460 22nd May 1995 FORTIETH ORDINARY SESSION (Third Part) The Baltic Assembly REPORT submitted on behalf of the Committee for Parliamentary and Public Relations by Mr. Masseret, Chairman and Rapporteur ASSEMBLY OF WESTERN EUROPEAN UNION 43, avenue du President-Wilson, 75775 Paris Cedex 16-Tel. 53.67.22.00 Document 1460 22nd May 1995 The Baltic Assembly REPORT 1 submitted on behalf of the Committee for Parliamentary and Public Relations 2 by Mr. Masseret, Chairman and Rapporteur TABLE OF CONTENTS DRAFr0RDER on the Baltic Assembly EXPLANATORY MEMORANDUM submitted by Mr. Masseret, Chairman and Rapporteur I. Introduction II. Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania: from political to parliamentary co-operation (a) Inter-state co-operation ( i) The Baltic Council (ii) Prospects for inter-state co-operation (b) Inter-regional co-operation (i) Nordic and Baltic co-operation (ii) European and transatlantic co-operation m. The Baltic Assembly: role and prospects (a) The political role of Baltic interparliamentary co-operation (i) co-operation between the Baltic Council and the Baltic Assembly (ii) The way the Assembly operates (b) The Baltic Assembly: regional and European political perspectives (i) Inter-state security and defence co-operation ( ii) Regional and European policy - Relations with the Russian Federation - European co-operation 1. Adopted unanimously by the committee. 2. M embers ofthe committee: Mr. Masseret (Chairman); Sir Russell J ohnston, Baroness Gould ofPotternewton (Vice-Chairmen); Mr. Amaral, Mrs. Beer, MM. Benvenuti, Birraux, Decagny, Dionisi, Sir Anthony Durant (Alternate: Baroness Hooper), Mr. Erler, Mrs. Err (Alternate: Mrs. Brasseur), Mr. Eversdijk, Mrs. Fernandez Sanz, MM. -

Eu Baltic Sea Strategy

EU BALTIC SEA STRATEGY REPORT FOR THE KONRAD-ADENAUER-STIFTUNG LONDON OFFICE www.kas.de This paper includes résumés and experts views from conferences and seminars facilitated and organised by the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung London and Centrum Balticum. Impressum © Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronical or mechanical, without permission in writing from Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, London office, 63D Eccleston Square, London SW1V 1PH. ABBREVIATIONS AC Arctic Council AEPS Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy ALDE Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe BaltMet Baltic Metropoles BCCA Baltic Sea Chambers of Commerce Association BDF Baltic Development Forum BEAC Barents Euro-Arctic Council BEAR Council of the Barents Euro-Arctic Region BENELUX Economic Union of Belgium, The Netherlands and Luxembourg BFTA The Baltic Free Trade Area BSCE Black Sea Economic Cooperation Pact BSPC The Baltic Sea Parliamentary Conference BSR Baltic Sea Region BSSSC Baltic Sea States Subregional Cooperation CBSS The Council for Baltic Sea States CFSP Common Foreign and Security Policy CEFTA Central European Free Trade Agreement CIS The Commonwealth of Independent States COMECON Council for Mutual Economic Assistance CPMR Conference of Peripheral Maritime Regions of Europe EBRD European Bank for Reconstruction and Development EEA European Economic Area EEC European Economic Community EFTA European Free Trade Agreement EGP European Green Party ENP European -

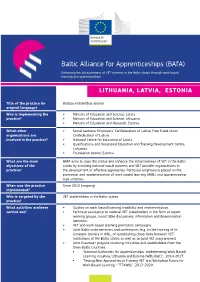

Baltic Alliance for Apprenticeships (Bafa) Enhancing the Attractiveness of VET Systems in the Baltic States Through Work-Based Learning and Apprenticeships

Baltic Alliance for Apprenticeships (BAfA) Enhancing the attractiveness of VET systems in the Baltic states through work-based learning and apprenticeships LITHUANIA, LATVIA, ESTONIA Title of the practice (in Baltijas māceklības alianse original language) Who is implementing the • Ministry of Education and Science, Latvia practice? • Ministry of Education and Science, Lithuania • Ministry of Education and Research, Estonia Which other • Social partners: Employers’ Confederation of Latvia, Free Trade Union organisations are Confederation of Latvia involved in the practice? • National Centre for Education of Latvia • Qualifications and Vocational Education and Training Development Centre, Lithuania • Foundation Innove, Estonia What are the main BAfA aims to raise the status and enhance the attractiveness of VET in the Baltic objectives of the states by involving national social partners and VET provider organisations in practice? the development of effective approaches. Particular emphasis is placed on the promotion and implementation of work-based learning (WBL) and apprenticeship- type schemes. When was the practice Since 2015 (ongoing) implemented? Who is targeted by the VET stakeholders in the Baltic states practice? What activities are/were • Studies on work-based learning feasibility and implementation. carried out? • Technical assistance to national VET stakeholders in the form of expert working groups, round table discussions, information and dissemination seminars. • VET and work-based learning promotion campaigns. • Joint Baltic-wide