Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(2722) Send Our Famous Crab Cakes Nationwide!

1725 Taylor Avenue • Parkville, Maryland 21234 410-661-4357 NATIONWIDE SHIPPING Visit PappasCrabCakes.com or Call 1-888-535-CRAB (2722) Send our Famous Crab Cakes Nationwide! Family Owned and Operated Since 1972 Crab Mac & Cheese Fried Zucchini Sticks A blend of creamy cheese baked with pasta and Lightly battered zucchini served with a lump crab meat, served with tricolor tortilla chips - 13.99 side of our special “Boom-Boom” sauce - 8.99 Mini Crab Cakes Fried Calamari Five of our FAMOUS Crab Cakes, just a smaller version - 15.99 Lightly dusted in flour and spices, then flash fried until golden brown, served with house marinara - 10.99 Seafood Sampler Crab Pretzel (4) crab balls, fried calamari, (4) sautéed shrimp A JUMBO braided soft pretzel, smothered in our crab dip with and (4) sautéed scallops - 26.99 extra crab meat and shredded jack cheeses on top - 13.99 Enough for two! Santa Fe Egg Rolls Crispy tortillas stuffed with chunks of white meat chicken, Fried Mozzarella beans, corn, and southwestern flavors, Not your average mozzarella stick! with a side of Mandarin duck sauce - 9.99 These are delicious, half-moon shaped fried mozzarella with house marinara for dipping - 8.99 Crab Dip Creamy and delicious! A homemade mixture of Chicken Tenders baked cheeses and crab meat with Old Bay, Chicken tenderloins, breaded and fried, served with warm pita bread - 14.99 with your choice of dipping sauce - 8.99 Try Buffalo Style for 1.00 more Spinach & Cheese Pie Spanakopita & Tiropita! Fresh spinach and feta in Stuffed Mushroom Caps flaky phyllo and a blend of cheeses in philo, Stuffed with crab meat blended with our award winning both baked until golden brown - 11.99 recipe and baked with imperial sauce - 15.99 Pappas’ Wings Quesadilla Ten of the most plump wings in town, tossed in your Shredded cheese with pico de gallo choice of BBQ, Buffalo, Chesapeake Spices, Cheese - 7.99 | Chicken - 10.99 | Crab - 14.99 Lemon Pepper, or try our TNT Buffalo - 10.99 1 lb. -

Menu Descriptions Packet

Moby Dicks Restaurant Menu & Descriptions Edited: March 2020 (prices not accurate for 2021) 11:30 AM to 9:30 PM late June through Labor Day (Closing earlier in off-season) 508.349.9795 3225 Rt. 6 Wellfleet, MA 02667 Mobys.com Soups Fried Platters Ask about quarts of soup to go! Served with French fries and cole slaw Cape Cod Clam ‘Chowdah’ Moby’s Fried Seafood Special Cup 5.75 Bowl 8.75 A heaping combination of Codfish, Scallops, Whole Belly Clams and Shrimp - MKT Lobster Bisque Cup 6.25 Bowl 9.25 Fish & Chips Absolutely the best! Hooked Atlantic cod - 19 Seafood Gumbo Lobster Cup 6.25 Bowl 9.25 We proudly serve premium hardshell Shrimp Platter lobsters coming from the cold Atlantic Wild white shrimp from the Gulf of Mexico - 19 waters. Starters Clam Strip Platter from local hard-shelled sea clams - 17 1.5 lb. or 2 lb. Lobster - MKT Moby’s Famous Outer Cape Onion Larger sizes when available or by special order A sweet Spanish onion, cut, battered and Scallop Platter deep-fried - 9 All lobsters steamed to order served with Day boat Cape Scallops - 25 drawn butter and corn on the cob. Nantucket Bucket Oyster Platter - 22 1lb. of steamers, 1lb. of mussels and corn Make it a New England Clambake Add Chatham Steamers and Potato - MKT on the cob - MKT Calamari Platter Rings & tentacles lightly fried - 16 Steamers Local Chatham steamers. Served with drawn Whole-Belly Clams butter and clam broth. 1lb. or 2lbs. - MKT Grilled & Broiled The perfect taste of Cape Cod - MKT Dinners Local Atlantic Mussels Fresh mussels steamed and served with Grilled Crab Cake Platter All served with potato & corn on cob. -

Fisheries and Aquaculture Economics

OLA FLAATEN FISHERIES AND AQUACULTURE ECONOMICS Download free eBooks at bookboon.com 2 Fisheries and Aquaculture Economics 2nd edition © 2018 Ola Flaaten & bookboon.com ISBN 978-87-403-2281-1 Peer review by Dr. Harald Bergland, Associate professor, School of Business and Economics, Campus Harstad, UiT The Arctic University of Norway Download free eBooks at bookboon.com 3 FISHERIES AND AQUACULTURE ECONOMICS CONTENTS CONTENTS Preface 11 Acknowledgements 12 Part I Introduction 13 1 Introduction 14 Part II Fisheries 22 2 Population dynamics and fishing 23 2.1 Growth of fish stocks 23 2.2 Effort and production 26 2.3 Yield and stock effects of fishing 29 Free eBook on Learning & Development By the Chief Learning Officer of McKinsey Download Now Download free eBooks at bookboon.com Click on the ad to read more 4 FISHERIES AND AQUACULTURE ECONOMICS CONTENTS 3 A basic bioeconomic model 36 3.1 Open access bioeconomic equilibrium 36 3.2 Maximising resource rent 42 3.3 Effort and harvest taxes 46 3.4 Fishing licences and quotas 52 4 Investment analysis 60 4.1 Discounting 60 4.2 Fish stocks as capital 63 4.3 Long-run optimal stock levels 67 4.4 Transition to long-run optimum 74 4.5 Adjusted transition paths 77 5 The Gordon-Schaefer model 83 5.1 The logistic growth model 83 5.2 The open-access fishery 85 5.3 Economic optimal harvesting 88 5.4 Discounting effects 92 6 Fishing vessel economics 98 6.1 Optimal vessel effort 98 6.2 Vessel behaviour in the long run 104 6.3 Quota price and optimal effort 105 6.4 A small-scale fisher’s choice of leisure time -

Something Is Happening to Our Fish Stocks

The oceans and us 1 The oceans and us Since man first gazed across its watery depths, the sea has been held in special regard. It has evoked visions of splendour and horror. It has provided life-sustaining riches and taken the lives of many in return. The sea is and continues to be a mystery, a symbolic representation of the forces of good and evil; of things that are beautiful and those that are beastly; of that which is human and that which is inspirational. The History of Seafood Of all the things that the oceans provide, perhaps the most important resource for us is the rich array of seafood which we harvest from its depths and shorelines across the world. More importantly, for those of us involved in the seafood industry, from the fishers who catch the fish, to the restaurant or deli owner that sells it, this seafood represents more than just a source of food; it is part of our culture, our heritage and our livelihood. Seafood may mean different things to different people. We may not know it but we all depend on the oceans To some, it is the height of luxury; an oyster still fresh in one way or another. from the sea shared over a glass of champagne. To others, it may be the daily meal, the fish brought home /ƚ ĐŽŶƚƌŽůƐ ŽƵƌ ĐůŝŵĂƚĞ͖ ǁŝƚŚŽƵƚ ƚŚĞ ŽĐĞĂŶ͛Ɛ after a long time at sea or some mussels gathered at low moderating effects on the weather, our days would be tide along the rocky shore. -

Ebook Download First Book of Sushi Ebook

FIRST BOOK OF SUSHI PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Amy Wilson Sanger | 1 pages | 01 Sep 2001 | Tricycle Press | 9781582460505 | English | Berkeley, CA, United States First Book Of Sushi PDF Book Jul 05, Brandy rated it it was amazing. Henry has discovered that the cupboard doors hidden behind his bedroom Add to Cart. It is actually technically misleading to say that "crucian carp" is used, as though any funa type carp in the genus may be substituted, especially since the true crucian carp is a distinct species altogether, C. Sputnik Sweetheart Paperback by Haruki Murakami. Authors Group Best for Glossary. The illustrations are creative. Cute book, thanks. Members save with free shipping everyday! For almost the next years, until the early 19th century, sushi slowly changed and the Japanese cuisine changed as well. When I With his multinational and ever expanding empire of twelve restaurants in the United States, United Kingdom, Italy and Japan he has become the most talked-about restaurateur of recent years and arguably the world's greatest sushi chef. Verified purchase: Yes Condition: Pre-owned. There is also a somewhat personal connection for me because I was raised around the Japanese culture and ate a lot of sushi when I was a young kid myself. The pictures are mainly paper cut outs. Join a group The story definitely uses Japanese words that some may not be so familiar with like "hamachi, maguro slice, futomaki, Ikura, tamago, shrimp ebi, and tobiko". Beautiful Pictures. Kathleen A. She lives with her family in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. Her love of food has inspired a lifelong education in many cuisines, including Japanese, Chinese, French, and Italian. -

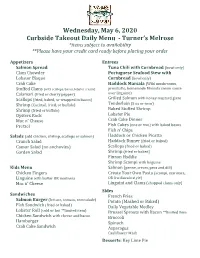

Wednesday, May 6, 2020 Curbside Takeout Daily Menu - Turner’S Melrose *Items Subject to Availability **Please Have Your Credit Card Ready Before Placing Your Order

Wednesday, May 6, 2020 Curbside Takeout Daily Menu - Turner’s Melrose *items subject to availability **Please have your credit card ready before placing your order Appetizers Entrees Salmon Spread Tuna Chili with Cornbread (bowl only) Clam Chowder Portuguese Seafood Stew with Lobster Bisque Cornbread (bowl only) Crab Cake Haddock Marsala (Wild mushrooms, Stuffed Clams (with scallops, bacon, lobster cream) prosciutto, homemade Marsala cream sauce Calamari (fried or cherry pepper) over linguine) Scallops (fried, baked, or wrapped in bacon) Grilled Salmon with honey mustard Glaze Shrimp (Cocktail, fried, or buffalo) Tenderloin (5 oz or twin) Shrimp (fried or buffalo) Baked Stuffed Shrimp Oysters Rock Lobster Pie Mac n’ Cheese Crab Cake Dinner Pretzel Fish Cakes (one or two) with baked beans Fish n’ Chips Salads (add chicken, shrimp, scallops or salmon) Haddock or Chicken Picatta Crunch Salad Haddock Dinner (fried or baked) Caesar Salad (no anchovies) Scallops (fried or baked) Garden Salad Shrimp (fried or baked) Finnan Haddie Shrimp Scampi with linguine Kids Menu Salmon (penne, cream, peas and dill) Chicken Fingers Create Your Own Pasta (scampi, marinara, Linguine with butter OR marinara OR fra diavalo style) Mac n’ Cheese Linguini and Clams (chopped clams only) Sides Sandwiches French Fries Salmon Burger (lettuce, tomato, remoulade) Potato (Mashed or Baked) Fish Sandwich (fried or baked) Daily Vegetable Medley Lobster Roll (cold or hot **limited item) Brussel Sprouts with Bacon **limited item Chicken Sandwich with cheese and bacon Broccoli -

Cracking MARKET PRICE 8Oz Roseda Farms Dry-Aged Petite Filet 44 Roasted Garlic Mashed Potatoes, Seasonal Vegetable Sautéed Musrooms, Peppercorn Steak Sauce

Maryland’s famous hard shell blue crabs are available seasonally and the chops are locally sourced upon availability. Order by the dozen or half dozen. Natty Boh's Beer Can Chicken HALF 24 • WHOLE 36 add on Let's get Crabs may vary in size by ½.” lemon & thyme whole roasted chicken, crab garlic mashed potatoes, seasonal vegetable imperial Choice of Medium, Large, Extra Large, or Jumbo to any dish $10 cracking MARKET PRICE 8oz Roseda Farms Dry-Aged Petite Filet 44 roasted garlic mashed potatoes, seasonal vegetable sautéed musrooms, peppercorn steak sauce ADD : CHICKEN 6 • SHRIMP 7 • STEAK 10 • TUNA 10 • CRAB CAKE 26 soups & salads 12oz Roseda Farms Dry-Aged New York Strip 44 roasted garlic mashed potatoes, seasonal vegetable Maryland Crab Soup CUP 8 • BOWL 14 Atlas Farms Bowl 12 sautéed musrooms, peppercorn steak sauce veggies, classic tomato broth, crab meat mixed greens, grilled corn, roasted sweet potatoes, radish, cucumber, heirloom tomatoes, farro, beet purée, lemon-herb vinaigrette Cream of Crab Soup CUP 8 • BOWL 14 eastern shore jumbo lump crab, sherry, old bay Ahi Tuna Salad 19 fried chicken Caesar Salad 12 mixed greens, radish, avocado, ponzu dressing, sesame choice of original or spicy nashville free range gem lettuce, garlic-herb croutons, parmesan, classic dressing crunch, red peppers, cucumber chicken, house batter, pickle, potato salad Half Chicken ......................................24 appetizers Choptank Cobb Salad 14 Kale Salad 14 chopped gem lettuce, bacon, tomato, corn, cucumber, dinosaur kale, spicy yogurt, truffled -

Placemat Menu

F A M I L Y M E A L E N T R E E S A D D - O N S BOARDWALK CRAB CAKE CREAM OF CRAB SOUP MEAL QUART $24 PINT $12 Four old-fashioned, down-the-ocean style MARYLAND CRAB SOUP made with local Maryland claw meat, lump QUART $22 PINT $11 crab, mustard and Old Bay, lightly fried $ 8 0 served three-mustard sauce C U R B S I D E C A R R Y - O U T BUTTERMILK BISCUITS & BUTTER (2) $3 F A M I L Y M E A L MARYLAND PAN-FRIED $ 6 8 M E N U CHICKEN MEAL CORNBREAD & BUTTER (4 PIECES) $3 Marinated chicken (8 thighs & 4 legs), Serves four Gertie’s secret seasoning, lightly fried BRIOCHE DINNER ROLLS & BUTTER (2) ALL MEALS INCLUDE: $4 CHOICE OF: TILGHMAN ISLAND $ 8 8 CAESAR SALAD KIT (SERVES 4) QUART OF MISS JEAN’S RED CRAB SOUP COMBO MEAL $20 OR Maryland Pan-fried chicken (8 thigh & 4 CAESAR SALAD KIT legs) and four Boardwalk Crab Cakes with GARLIC MASHED POTATOES three-mustard sauce QUART $9 PINT $5 QUART OF COUNTRY POTATO SALAD ROASTED GARLIC, CARAMELIZED ONIONS, MIX BELL COUNTRY POTATO SALAD PEPPERS $ 8 8 QUART $9 PINT $5 ED’S BBQ RIBS & QUART OF SLOW-BRAISED GREEN BEANS FRIED CHICKEN SLOW-BRAISED GREEN BEANS ONIONS, TOMATOES, BACON Full rack of Memphis-style bbq baby back QUART $9 PINT $5 pork ribs, Maryland pan-fried chicken (8 BUTTERMILK BISCUITS (4) & BUTTER thigh & 4 legs), cornbread & butter BOX OF HOUSE-MADE FRIES [GF] $9 CHEFS SWEET TREAT DESSERT OF THE DAY H O U R S : APPLE-FENNEL SLAW W E D N E S D A Y - S A T U R D A Y QUART $8 PINT $4 G L U T E N F R E E - G F 4 : 0 0 P M - 8 : 0 0 P M V E G E T A R I A N - V G V E G A N - V N S U N D A Y -

Making Sense of Sustainable Seafood Certifications

Making Sense of Sustainable Seafood Certifications The Honors Program Senior Capstone Project Student’s Name: Samantha Yoder Faculty Sponsor: John Visich April, 2017 Table of Contents Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 2 Sustianability Campaigns .......................................................................................................... 4 Certification Programs .......................................................................................................... 4 Recommendation Lists .......................................................................................................... 5 Confusion .............................................................................................................................. 6 Sustainable Seafood Supply Chains .......................................................................................... 7 History of the Seafood industry ................................................................................................ 8 The Creation of the Seafood Industry ................................................................................... 8 Emergence of the Sustainable Seafood Movement ................................................................... 9 Rise of Consumer Demand for Sustainably Certified Products -

Persistent Seafood Fraud Found in South Florida

Persistent Seafood Fraud Found in South Florida July 2012 Authors: Kimberly Warner, Ph.D., Walker Timme, Beth Lowell and Margot Stiles Executive Summary In Florida, the state’s residents and its visitors enjoy eating and catching seafood. In fact, Floridians eat twice as much seafood as the average American. At the same time, Florida has a long history of uncovering and addressing seafood fraud, specifically the substitution of one species of fish for another less desirable or less expensive species. Oceana recently investigated seafood mislabeling in South Florida as part of a campaign to Stop Seafood Fraud. The results were disturbing. Nearly a third of the seafood tested was mislabeled in some way, leaving consumers with little ability to know what they are eating or feeding their families, and even less ability to make informed choices that promote sustainable fishing practices, or even protect their health. Key Findings: Overall, Oceana found 31% of seafood mislabeled in the Miami/Fort Lauderdale-area in this 2011/12 survey. Fraud was detected in half of the 14 different types of fish collected, with snappers and white tuna being the most frequently mislabeled. • Red snapper was mislabeled 86% of the time (six out of seven samples). • Grouper, while mislabeled at a lower level (16% of the time), had one of the most egregious substitutions: one fish sold as grouper was actually king mackerel, a fish that federal and state authorities advise women of childbearing age not to eat due to high mercury levels, which can harm a developing fetus. • Atlantic salmon was substituted for wild or king salmon 19% of the time (one in five times). -

Seafood Expo North America and Seafood Processing North America

2017 ISSUE Seafood Expo North America and Seafood Processing North America THE OFFICIAL SHOW GUIDE Brought to you by: PAGE 6 Shuttle Schedule PAGE 32 Show Map PAGE 30 Boston Dining Guide PAGE 40 Conference Schedule March 19-21, 2017 panamei.com ©2017, Panamei Seafood. All rights reserved. Cool Chain... Logistics for the Seafood Industry! From Sea to Serve. Lynden’s Cool Chain℠ service manages your seafood supply chain from start to fi nish. Fresh or frozen seafood is transported at just the right speed and temperature to meet the particular needs of the customer and to maintain quality. With the ability to deliver via air, highway, or sea or use our temperature-controlled storage facilities, Lynden’s Cool Chain℠ service has the solution to your seafood supply challenges. lynden.com | 1-888-596-3361 Booth #280 WELCOME TO BOSTON Taking care of business Welcome (or welcome back) to Seafood Expo North America, the largest seafood expo on the continent. BE SURE TO s those who have attended before know, the expo Apacks a lot into its three days, with more than a STOP BY thousand exhibitors ready to do business, an extensive BOOTH 1301 educational conference program chock full of engaging TO SHARE speakers and interesting topics, and fun events like the YOUR NEWS 11th Annual Oyster Shucking Contest and the Seafood WITH THE Excellence Awards Ceremony. With an event of SENA’s magnitude, it’s difficult to SEAFOOD stay organized. To keep it all straight, SeafoodSource EXPO TEAM! has put together the Expo Today you’re holding in your hands right now. -

December 2020

Welcome to Feeser’s Family Owned For Over 100 Years We supply everything but the appetite... What began in 1901 as a small local produce company in downtown Harrisburg, has grown into a large food distribution company, employing hundreds of Central Pennsylvania residents. Still family owned and operated, Feeser’s is now located on over 20 acres including 275,000 square feet of warehouse facilities with cooler, freezer and dry storage capabilities. Feeser’s services restaurants, schools, entertainment, sports, and other foodservice facilities across the Mid-Atlantic Region in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia. Visit us at the new feesers.com. For information or to order any of the products in this publication, contact our Sales Team at 717.564.4636 or DECEMBER 2020 REPRESENTED BRANDS AND MANUFACTURERS CAMPBELL’S CARGILL CONAGRA GENERAL MILLS HANDY SEAFOOD KELLOGG’S KRAFT HEINZ LAMB WESTON NESTLE PROFESSIONAL P&G PROFESSIONAL PEAK SALES & MARKETING PERDUE SARA LEE SIMPLOT TYSON UNILEVER FOOD SOLUTIONS Serve more. save More. Whether you’re looking to stock up on versatile speed-scratch favorites or add to your grab-and-go lineup, we’re here to help you save on the products below. As the cases add up, so do the savings. To qualify, purchase a minimum of 10 cases from any one category. Purchase from additional product categories and save even more per case. Purchases must be made between September 1st and December 31st, 2020. rebate level 1 rebate level 2 Buy at least 10 cases from one category and get Buy at least 10 cases from two categories (minimum 20 cases) and get back per case.