Defence Strategic Communications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Defence Strategic Communications

Defence Strategic Communications | Volume 5 | Autumn 2018 DEFENCE STRATEGIC COMMUNICATIONS DEFENCE STRATEGIC 12 Volume 5 | Autumn 2018 DEFENCE STRATEGIC COMMUNICATIONS The official journal of the NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence AUTUMN 2018 The Acoustic World of Influence: How Musicology Illuminates Strategic Communications Hostile Gatekeeping: the Strategy of Engaging With Journalists in Extremism Reporting The ‘Fake News’ Label and Politicisation of Malaysia’s Elections Brand Putin: an Analysis of Vladimir Putin’s Projected Images What Does it Mean for a Communication to be Trusted? Strategic Communications at the Pyeongchang Winter Olympics: a Groundwork Study ISSN: 2500-9486 DOI: 10.30966/2018.RIGA.5. Defence Strategic Communications | Volume 5 | Autumn 2018 DOI 10.30966/2018.RIGA.5.5 WHAT DOES IT MEAN 171 FOR A COMMUNICATION TO BE TRUSTED? Francesca Granelli Abstract Despite following best practice, most governments fail in their strategic communications. There is a missing ‘X’ factor: trust. This offers a quick win to strategic communicators, provided they understand what the phenomenon involves. Moreover, it allows practitioners to avoid the risk of citizens feeling betrayed when their government fails to deliver. Keywords: trust, communications, impersonal trust, distrust, reliance, co-operation, strategic communications About the author Dr Francesca Granelli is a Teaching Fellow at King’s College London, where her research focuses on trust. Her forthcoming book is Trust, Politics and Revolution: A European History. Defence Strategic Communications | Volume 5 | Autumn 2018 DOI 10.30966/2018.RIGA.5.5 172 Introduction Governments, politicians, and commentators are worried. The ‘crisis of trust’ is now a common refrain, which draws upon a mountain of apparent evidence.1 Edelman’s Trust Barometer, for instance, points to declining levels of trust in governments, NGOs, businesses, and the media across most countries each year. -

Read the SPUR 2012-2013 Annual Report

2012–2013 Ideas and action Annual Report for a better city For the first time in history, the majority of the world’s population resides in cities. And by 2050, more than 75 percent of us will call cities home. SPUR works to make the major cities of the Bay Area as livable and sustainable as possible. Great urban places, like San Francisco’s Dolores Park playground, bring people together from all walks of life. 2 SPUR Annual Report 2012–13 SPUR Annual Report 2012–13 3 It will determine our access to economic opportunity, our impact on the planetary climate — and the climate’s impact on us. If we organize them the right way, cities can become the solution to the problems of our time. We are hard at work retrofitting our transportation infrastructure to support the needs of tomorrow. Shown here: the new Transbay Transit Center, now under construction. 4 SPUR Annual Report 2012–13 SPUR Annual Report 2012–13 5 Cities are places of collective action. They are where we invent new business ideas, new art forms and new movements for social change. Cities foster innovation of all kinds. Pictured here: SPUR and local partner groups conduct a day- long experiment to activate a key intersection in San Francisco’s Mid-Market neighborhood. 6 SPUR Annual Report 2012–13 SPUR Annual Report 2012–13 7 We have the resources, the diversity of perspectives and the civic values to pioneer a new model for the American city — one that moves toward carbon neutrality while embracing a shared prosperity. -

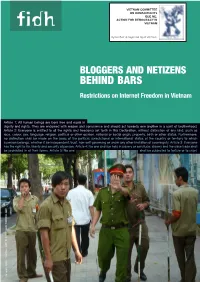

Bloggers and Netizens Behind Bars: Restrictions on Internet Freedom In

VIETNAM COMMITTEE ON HUMAN RIGHTS QUÊ ME: ACTION FOR DEMOCRACY IN VIETNAM Ủy ban Bảo vệ Quyền làm Người Việt Nam BLOGGERS AND NETIZENS BEHIND BARS Restrictions on Internet Freedom in Vietnam Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. Article 2: Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty. Article 3: Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person. Article 4: No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms. Article 5: No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, January 2013 / n°603a - AFP PHOTO IAN TIMBERLAKE Cover Photo : A policeman, flanked by local militia members, tries to stop a foreign journalist from taking photos outside the Ho Chi Minh City People’s Court during the trial of a blogger in August 2011 (AFP, Photo Ian Timberlake). 2 / Titre du rapport – FIDH Introduction ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------5 -

Graphic Evangelism 1

Running head: GRAPHIC EVANGELISM 1 Graphic Evangelism The Mainstream Graphic Novel for Christian Evangelism Mark Cupp A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2013 GRAPHIC EVANGELISM 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Edward Edman, MFA Thesis Chair ______________________________ Chris Gaumer, MFA Committee Member ______________________________ Ronald Sumner, MFA Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date GRAPHIC EVANGELISM 3 Abstract This thesis explores the use of mainstream graphic novels as a means of Christian evangelism. Though not exclusively Christian, the graphic novel, The Beast Within, will educate its target audience by using attractive illustrations, relatable issues, and understandable morals in a fictional, biblically inspired story. This thesis will include character designs, artwork, chapter summaries, and a single chapter of a self-written, self- illustrated graphic novel along with a short summary of Christian references and symbols. The novel will follow six half-human, half-animal warriors on their adventure to restore the balance of their world, which has been disrupted by a powerful enemy. GRAPHIC EVANGELISM 4 Graphic Evangelism The Mainstream Graphic Novel for Christian Evangelism Introduction As recorded in Matthew 28:16-20, all Christians are commanded by Christ to spread the Gospel to all corners of the earth. Many believers almost immediately equate evangelism to Sunday morning services, church mission trips, or distribution of witty, ever-popular salvation tracts; however, Jesus utilized other methods to teach His people, such as telling simple stories and using familiar images and illustrations. -

FLEXIBLE BENEFITS for the GIG ECONOMY Seth C. Oranburg* Federal Labor Law Requires Employers to Give

UNBUNDLING EMPLOYMENT: FLEXIBLE BENEFITS FOR THE GIG ECONOMY Seth C. Oranburg∗ ABSTRACT Federal labor law requires employers to give employees a rigid bundle of benefits, including the right to unionize, unemployment insurance, worker’s compensation insurance, health insurance, family medical leave, and more. These benefits are not free—benefits cost about one-third of wages—and someone must pay for them. Which of these benefits are worth their cost? This Article takes a theoretical approach to that problem and proposes a flexible benefits solution. Labor law developed under a traditional model of work: long-term employees depended on a single employer to engage in goods- producing work. Few people work that way today. Instead, modern workers are increasingly using multiple technology platforms (such as Uber, Lyft, TaskRabbit, Amazon Flex, DoorDash, Handy, Moonlighting, FLEXABLE, PeoplePerHour, Rover, Snagajob, TaskEasy, Upwork, and many more) to provide short-term service- producing work. Labor laws are a bad fit for this “gig economy.” New legal paradigms are needed. The rigid labor law classification of all workers as either “employees” (who get the entire bundle of benefits) or “independent contractors” (who get none) has led to many lawsuits attempting to redefine who is an “employee” in the gig economy. This issue grows larger as more than one-fifth of the workforce is now categorized as an independent contractor. Ironically, the requirement to provide a rigid bundle of benefits to employees has resulted in fewer workers receiving any benefits at all. ∗ Associate Professor, Duquesne University School of Law; Research Fellow and Program Affiliate Scholar, New York University School of Law; J.D., University of Chicago Law School; B.A., University of Florida. -

Skripsi Politik Mahathir Mohamad Dalam Pemilihan

SKRIPSI POLITIK MAHATHIR MOHAMAD DALAM PEMILIHAN PERDANA MENTERI MALAYSIA TAHUN 2018 OLEH: DAFFA RIYADH AZIZ 150906023 Dosen Pembimbing: Dr. Warjio Ph.D DEPARTEMEN ILMU POLITIK FAKULTAS ILMU SOSIAL DAN ILMU POLITIK UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2019 Universitas Sumatera Utara SURAT PERNYATAAN BEBAS PELAGIAT Saya yang bertanda tangan di bawah ini: Nama : Daffa Riyadh Aziz NIM : 150906023 Judul Skripsi : POLITIK MAHATHIR MOHAMAD DALAM PEMILIHAN PERDANA MENTERI MALAYSIA TAHUN 2018 Dengan ini menyatakan: 1. Bahwa skripsi yang saya tulis benar merupakan tulisan saya dan bukan hasil jiplakan dari skripsi atau karya ilmiah orang lain 2. Apabila terbukti dikemudian hari skipsi ini merupakan hasil jiplakan maka saya siap menanggung segala akibat hukumnya Demikian pernyataan ini saya buat sebenar-benarnya tanpa ada paksan atau tekanan dari pihak manapun. Medan, 11 Juli 2019 Daffa Riyadh Aziz 150906023 Universitas Sumatera Utara UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA FAKULTAS ILMU SOSIAL DAN ILMU POLITIK Halaman Pengesahan Skripsi ini telah dipertahankan dihadapan panitia penguji skripsi Departemen Ilmu Politik Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik Universitas Sumatera Utara. Dilaksanakan pada: Hari : Tanggal : Pukul : Tempat : Tim Penguji: Ketua Penguji : Muhammad Ardian, S.Sos., M.I.Pol ( ) NIP. 198502242017041001 Penguji Utama Warjio, Ph.D ( ) NIP. 197408062006041003 Penguji Tamu : Fernanda Putra Adela, S.Sos, M.Si ( ) NIP. 198604032015041001 Universitas Sumatera Utara UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA FAKULTAS ILMU SOSIAL DAN ILMU POLITIK Halaman Persetujuan Skripsi ini disetujui untuk dipertahankan dan diperbanyak oleh Nama : Daffa Riyadh Aziz NIM : 150906023 Departemen : Ilmu Politik Judul : POLITIK MAHATHIR MOHAMAD DALAM PEMILIHAN PERDANA MENTERI MALAYSIA TAHUN 2018 Menyetujui: Ketua Departemen Ilmu Politik Dosen Pembimbing Warjio, Ph. D Warjio, Ph. D NIP. 197408062006041003 NIP. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

The Taib Timber Mafia

The Taib Timber Mafia Facts and Figures on Politically Exposed Persons (PEPs) from Sarawak, Malaysia 20 September 2012 Bruno Manser Fund - The Taib Timber Mafia Contents Sarawak, an environmental crime hotspot ................................................................................. 4 1. The “Stop Timber Corruption” Campaign ............................................................................... 5 2. The aim of this report .............................................................................................................. 5 3. Sources used for this report .................................................................................................... 6 4. Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................. 6 5. What is a “PEP”? ....................................................................................................................... 7 6. Specific due diligence requirements for financial service providers when dealing with PEPs ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 7. The Taib Family ....................................................................................................................... 9 8. Taib’s modus operandi ............................................................................................................ 9 9. Portraits of individual Taib family members ........................................................................ -

'Just Leave Me Alone': Social Isolation and Civic Disengagement for The

‘Just Leave Me Alone’: Social Isolation and Civic Disengagement for the Small-City Poor INTRODUCTION The sprawling desert community of Riverway1, Washington is neither a booming city nor a persistently poor one. For its small size, it enjoys a relatively healthy economy, and has few identifiable pockets of high-density poverty. Yet, like most of the nation, it suffered significant job loss during the economic downturn of 2007-2009 (Washington State Employment Security Department 2012). Once a collection of small farm towns, Riverway had undergone rapid population growth and unmitigated sprawl in recent decades, as suburban housing developments, apartment complexes, strip-malls, and big- box stores spread into land that had been orchards and vineyards. As it grew, low-skilled individuals from both bigger cities and smaller rural communities flocked to Riverway in search of low-cost housing and job opportunities in its expanding construction and service sectors; many of them struggled when the recession hit. Although many came to Riverway specifically because of social ties there, a combination of social, cultural, structural and spatial barriers contributed to isolation amongst this population, limiting their options for survival as well as capacities for and interest in social and civic life. This paper, based on qualitative interviews and ethnographic observation, looks at the social repercussions of job loss and poverty in a type of community where they are rarely studied (Norman 2013): a small, postagrarian (Salamon 2003), sprawling Western city. Despite the tendency for sociological inquiry on poverty to focus on high-density and persistently poor communities, there is evidence that since the recession poverty is 1 becoming an increasing problem in small metropolitan areas and suburbs (Fessler 2013; Kneebone and Garr 2010). -

Wellness Bliss

Wellness bliss. Tour designer: Steffanie Tan Telephone: (+60) 4 376 1101 Email: [email protected] Tour designer: Steffanie Tan Telephone: (+60) 4 376 1101 Email: [email protected] MALAYSIA | 8DAYS / 7NIGHTS Route: Round-trip from Kuala Lumpur to Langkawi Type of tour: Cultural and wellness 1 TOUR OVERVIEW Discover the sensuous side of Malaysia over eight days of sheer and utter bliss, with a heavenly mix of sightseeing and therapeutic treatments. This twin centre programme takes in the futuristic capital, Kuala Lumpur, and the paradisiacal island of Langkawi in the Andaman Sea. Visit shrines, workshops and markets; explore caves and mangrove swamps, and come face to face with the king of birds at an eagle feeding session; and enjoy an array of relaxing traditional Malaysian massages from the moment you arrive to the eve of your departure. TOUR HIGHLIGHTS Kuala Lumpur: Tour the world-famous Royal Selangor visitor centre and learn all about pewter production Batu caves: These limestone caverns to the north of Kuala Lumpur are a shrine to Hindu deity Lord Subramaniyan Chinatown: Stroll through the bustling Pasar Malam night market for an insight into the Kuala Lumpur’s thriving Chinese community Langkawi: Release your inner Indiana Jones touring the mangroves and caves of this island known as the Jewel of Kedah DON'T MISS KL Tower: The 421-metre-tall telecom Little India: One in ten Kuala Lumpur Langkawi: Savour the fresh seafood tower offers stunning views of Kuala residents is of Indian origin and that is available at a number of Lumpur and the PETRONAS Twin Brickfields is the beating heart of this restaurants throughout Langkawi. -

No. Soalan: 355

NO. SOALAN: 355 PEMBERITAHUAN PERTANYAAN BAGI JAWAB BUKAN LISAN DEWAN RAKYAT PERTANYAAN BUKAN LISAN DARIPADA TUAN IDRIS BIN HAJI AHMAD [ BUKIT GANTANG ] RUJUKAN 9120 SO ALAN Tuan Idris bin Haji Ahmad [ Bukit Gantang ] minta MENTERI DALAM NEGERI menyatakan senarai nama-nama parti politik yang masih aktif dan sah berdaftar dengan pejabat Pendaftar Pertubuhan di negara ini. 1 JAWAPAN: Sehingga 31 Disember 2015, sebanyak 58 buah parti politik yang telah didaftarkan di bawah Akta Pertubuhan 1966 (Akta 335). Senarai parti politik tersebut adalah seperti berikut:- 1 Parti Nasional Malaysia I Malaysian National Party( MNP) 2 Barisan Jamaah lslamiah Se Malaysia (BERJASA) Parti Nasional Penduduk Malaysia (People's National Party Of 3 Malaysia) 4 Parti Cinta Malaysia (PCM) 5 Parti Bersatu Bugis Sabah 6 Parti Bersatu Rakyat Sabah 7 Parti Bersatu Sabah (PBS) 8 Parti Bersatu Sasa Malaysia 9 Parti Cinta Sabah (PCS) 10 Parti Damai Sabah (Sabah Peace Party) (Parti SPP) --------; 11 Parti Ekonomi Rakyat Sabah (PERS) 12 Parti Gagasan Bersama Rakyat Sabah (Parti BERSAMA) ---------< 13 Parti Kebangsaan Sabah (PKS) 14 Parti Kebenaran Sabah (KEBENARAN) 15 Parti Liberal Demokratik (LOP) 16 Parti Maju Sabah (PMS) Parti Pembangunan Warisan Sabah I Sabah Heritage Development 17 Party 18 Parti Sejahtera Angkatan Perpaduan Sabah (SAPU) Pertubuhan Kebangsaan Sabah Bersatu (USNO) I United Sabah 19 National Organisation (USNO) 20 Pertubuhan Pasokmomogun Kadazandusun Murut Bersatu (UPKO) 21 Pertubuhan Perpaduan Rakyat Kebangsaan Sabah (PERPADUAN) 22 Parti Bangsa Dayak -

An Analysis of Low-Income Black Students and Educational Outcomes

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2015 What's "Black" Got to Do With It: An Analysis of Low-Income Black Students and Educational Outcomes Derrick E. Griffith Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/568 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] WHAT’S “BLACK” GOT TO DO WITH IT? AN ANALYSIS OF LOW-INCOME BLACK STUDENTS AND EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES by DERRICK EUGENE GRIFFITH A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Urban Education in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York (2015) © 2015 Derrick E. Griffith All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted by the graduate Faculty in Urban Education in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Juan Battle ________________________ _________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Anthony Picciano _________________________ _________________________ Date Executive Officer Anthony Picciano Nicholas Michelli Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT WHAT’S “BLACK” GOT TO DO WITH IT? AN ANALYSIS OF LOW-INCOME BLACK STUDENTS AND EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES by Derrick Eugene Griffith Adviser: Professor Juan Battle Well-known social scientist William Wilson notes the Black underclass is particularly at risk of developing behaviors and attitudes that promote educational and social isolation.